During the afternoons I teach a small group of highly susceptible kids. They are easily influenced because of their age, which is around 9-12 years. Besides Thursdays and Fridays I have a group of only boys. I have my hands full, but a lot about the male specie becomes clear to me as I watch these boys. They are forever ranting about Comic Books. Of course I share this passion, so we often discuss certain comic book characters etc. I always tell the boys that violence is bad (I mean, when I give a piece of clay to a girl, she will start kneading it and start problem solving about how she would produce a beautiful item. When I give a ball of clay to a boy, chances are he would threaten to throw another boy with it,or, like one boy actually did, start throwing it to the floor as hard as he can to see if he can flatten it in that manner.) One boy said he is going to draw `Thor´ for me, so I asked if there are no female characters he can draw for me and he replied sure, he´ll draw ´Invisible woman`. I am trying to find ways to teach these boys to become real men. And I´m not so sure the comic books are helping. I really love the work of Alan Moore, and recently came across his Invisible Girls and Phantom Ladies.

In his essay ‘And all right, we need a woman’: victimized heroines and heroic victims in Alan Moore’s quasi-Victorian graphic novels`, Maciej Sulmicki writes:

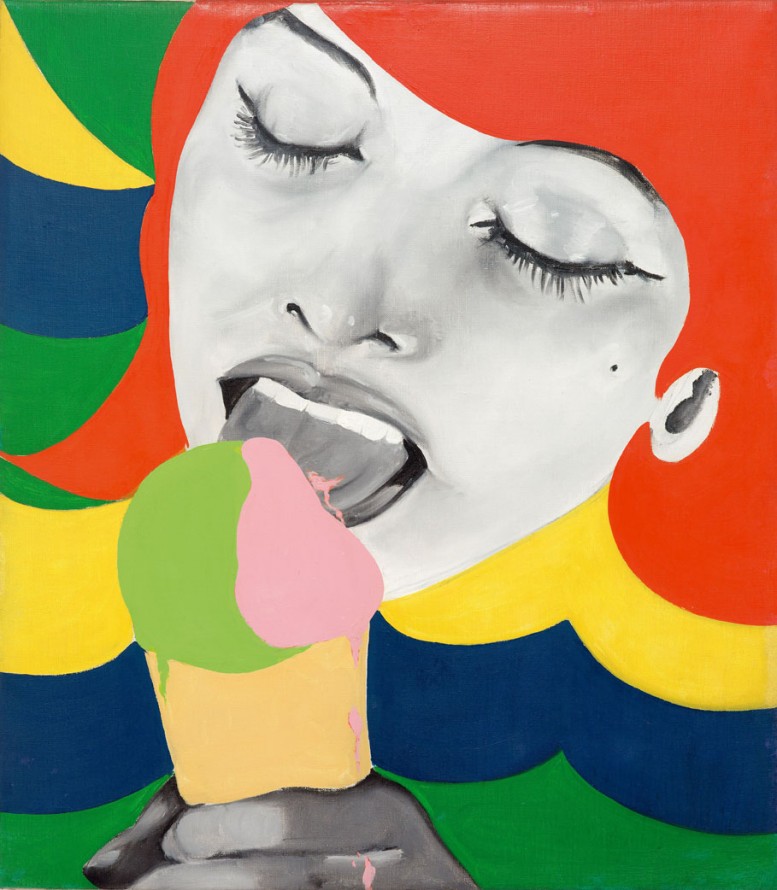

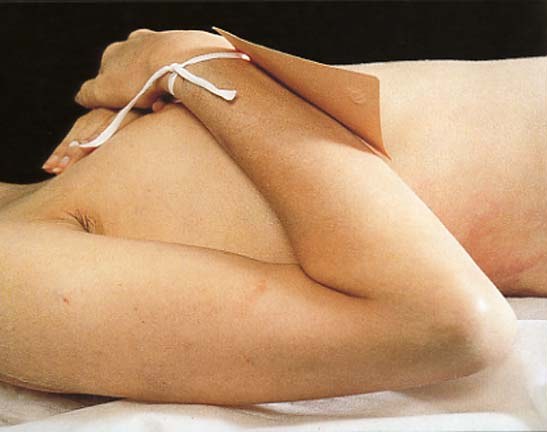

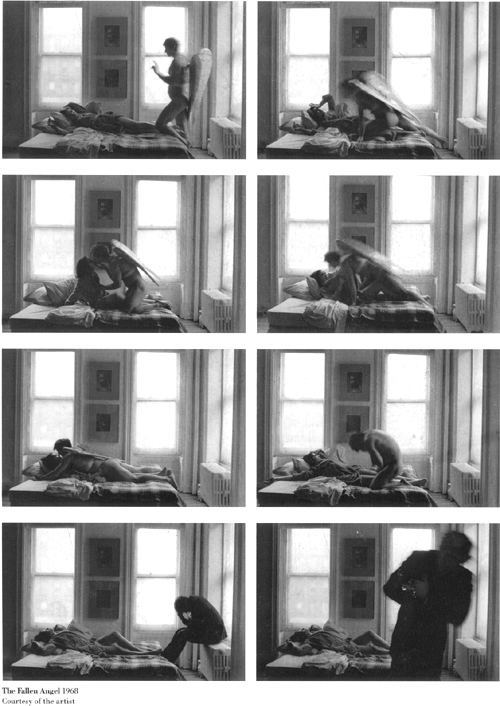

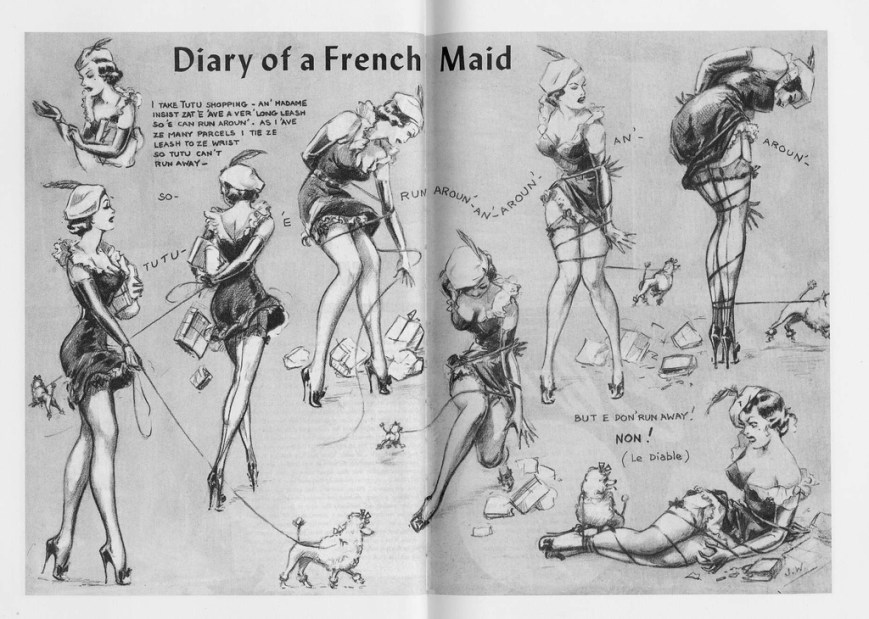

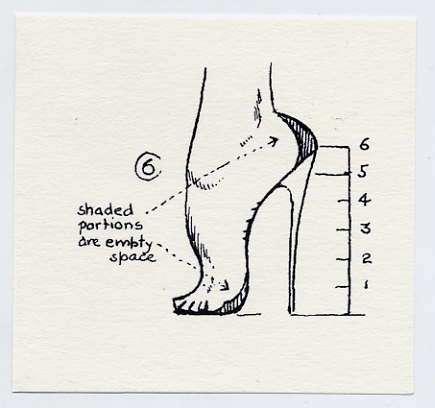

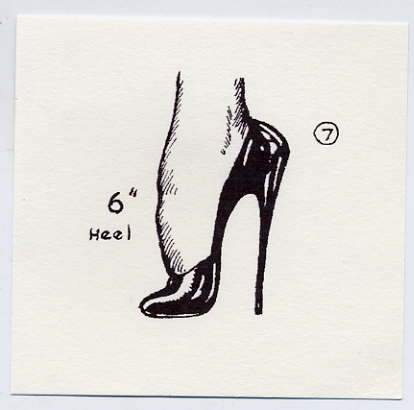

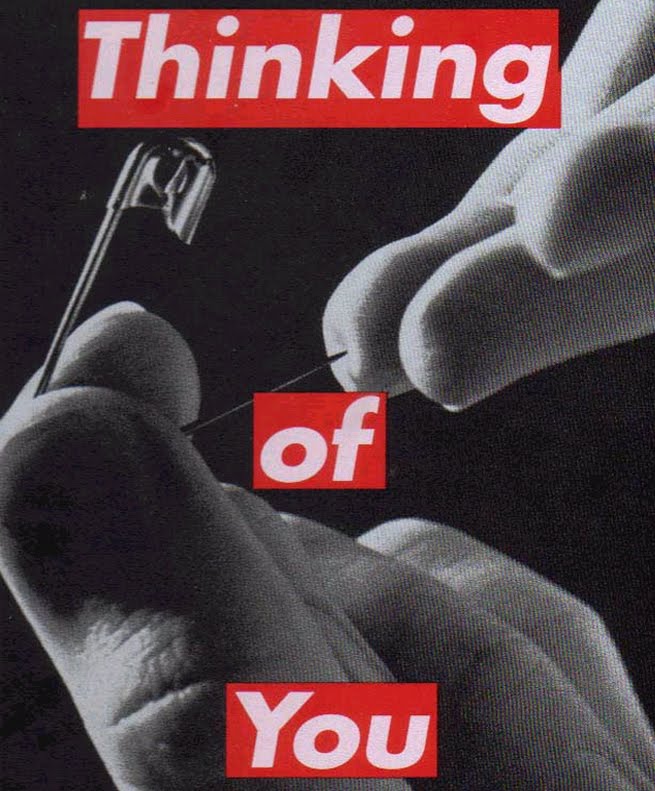

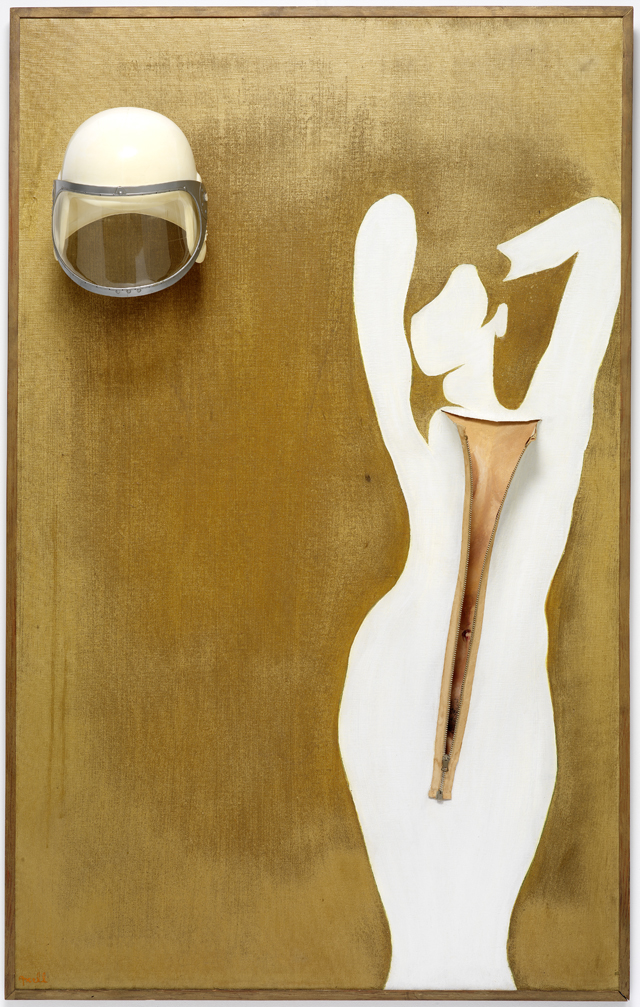

“Moore has long ago declared an interest in the image of women in comics books and recently confirmed that he has always felt ‘that [women’s problems] was an area that needed to be addressed’. 25 years ago, in a three-installment essay in The Daredevils he wrote of ‘Invisible Girls and Phantom Ladies’, i.e. sexism in comics. Although the text is written in a jocular tone, the main message is quite serious: that comics are rather fueling sexism and gender inequality than combating them. Women in mainstream comics are said to serve primarily as decoration, especially in visual terms, this being the case even when the female characters have something important to say. Such an approach to the visual presentation of females is a continuation of a long-standing tradition, visible as early as in comic strips from the first half of the twentieth century. Moore claims, however, that graphic depiction is not as important as the type of character as which the woman is presented. Both ‘helpless quivering victims’ and pale copies of female superheroes, as well as examples of rough ‘Marvel-style’ feminism serve to fuel stereotypes. In the case of the first two, scantily-clad and often captured and tied up heroines are accused of fueling ‘sordid adult fantasies’ and ideas such as women enjoying being raped. In the final installment of the essay Moore opines that the masculine world of comics is unlikely to significantly change its approach in favor of equal rights unless it is motivated from the outside – by the readers.”

Moore´s Invisible Girls and Phantom Ladies: Originally published in The Daredevils #4 – #6 (Marvel UK, April – June 1983)

PART I

Okay. Seeing as this is such a sticky subject suppose I’d better lay my cards on the table straight away.

I’m a wimpy, indecisive, burned-out woolly-minded liberal old hippy who eats quiche, saves whales, is friendly to the Earth and subscribes to Spare Rib, The Black One-Parent Gay Catholic Gazette, and Animal Welfare Against Nuking the Nazis Quarterly and if anybody wants to make anything of it, then I’ll quite cheerfully butt them in the face until their nose is flat enough to rollerskate on.

The reason I’m prepared to make such a candid confession is because I’m pretty sure that after reading the article in hand most of you will be saying pretty much the same things about me anyway and I thought it’d look better if I got in first. And the reason I’m donning my Sou’Wester in preparation for a torrent of abuse is because this feature concerns women, and women don’t seem to be a very popular topic nowadays. There are a couple of possible reasons for this sad state of affairs.

The first is that a small but vocal percentage of feminists are quite obviously as mad as snakes and have hopelessly damaged personalities. They pounce with demented glee upon increasingly trivial and unimportant examples of ‘sexism’, they make outrageously twisted and generalised statements to the Press along the lines of “All men are rapists“, and in general make themselves very difficult to like.

The problem arises when these foaming maniacs are presented in the media as being a representative cross section of the women’s movement, thus reinforcing the image of feminism that most men are only too eager to accept as the truth: an army of crop-haired Amazon gargoyles who chainsmoke untipped Woodbines, shift cement blocks for a living and have a physique somewhere between that of Popeye and a Commer van.

The other reason is that men, over the last few thousand years, have come to enjoy the perks and privileges that are part and parcel of being born into the male gender and are very reluctant to give them up. Men in general are a pretty insecure bunch and when they start to feel threatened by something they tend to respond by hurling forth salvoes of scorn and contempt, or, failing that, they refuse to take the issue seriously at all.

Even generally broadminded people who believe that the abolition of slavery in America was by and large a good thing seem to get very defensive and hysterical when it’s their Sunday Lunch that’s being threatened by the Women’s Movement. My guess is that if these gentlemen had been Southern Plantation owners they’d have felt the same reluctance in forgoing the pleasures of their Negro house-boy bringing them a Mint Julep on the veranda.

All right. So that’s the basic situation, and it’s one that is obscured by a lot of bluster, silliness and ratbrainery on both sides. But once you’ve swept away all the damned lies and statistics, it becomes plain that there really is a serious problem under there somewhere. Women in general are not really getting a fair suck of the sauce-stick, and it’s not just in obvious areas like equal pay for equal work and who brings up baby.

These areas are obviously important, but they’re all symptoms that spring from a central illness, an illness that affects the way it which we see women and the way we treat them in our largely male-oriented society.

The media presents us with a number of different stereotypes to choose from when forming our ideas of womanhood. There’s a wide variety of different designs, and they’re all about as palatable as a lobster with skin cancer. Continue reading

At the outbreak of World War II, Miller was living in Hampstead, London with Roland Penrose when the bombing of the city began. Ignoring pleas from friends and family to return to the US, Miller embarked on a new career in photojournalism as the official war photographer for Vogue, documenting the Blitz. Lee was accredited into the U.S. Army as a war correspondent for Condé Nast Publications from December 1942.

At the outbreak of World War II, Miller was living in Hampstead, London with Roland Penrose when the bombing of the city began. Ignoring pleas from friends and family to return to the US, Miller embarked on a new career in photojournalism as the official war photographer for Vogue, documenting the Blitz. Lee was accredited into the U.S. Army as a war correspondent for Condé Nast Publications from December 1942.