“Louise Bourgeois and Tracey Emin both blur the boundary between art and life is by pouring the turbulent history of an individual’s psyche into the work. The difference between them is that, for Bourgeois, life seeps into art, whereas for Emin, life collides with art. Do Not Abandon Me brings together these two approaches to also blur the boundary between two individuals’ life histories in a moving, sometimes upsetting and admirable collection of work.

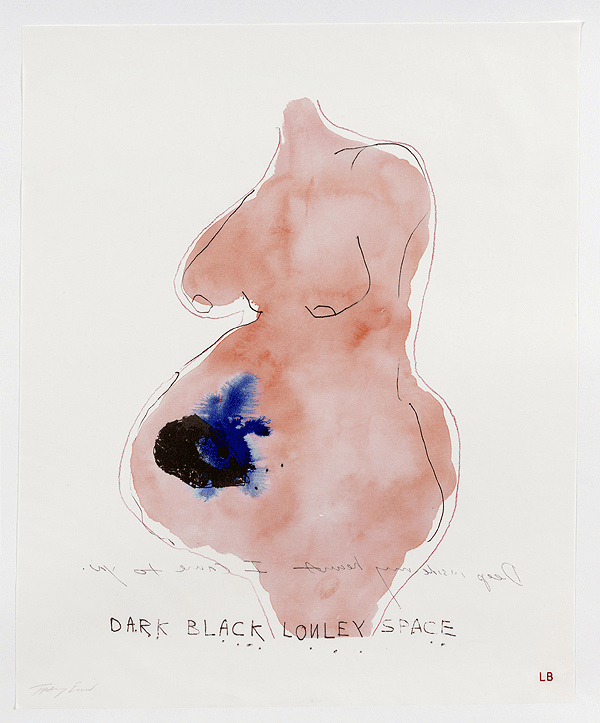

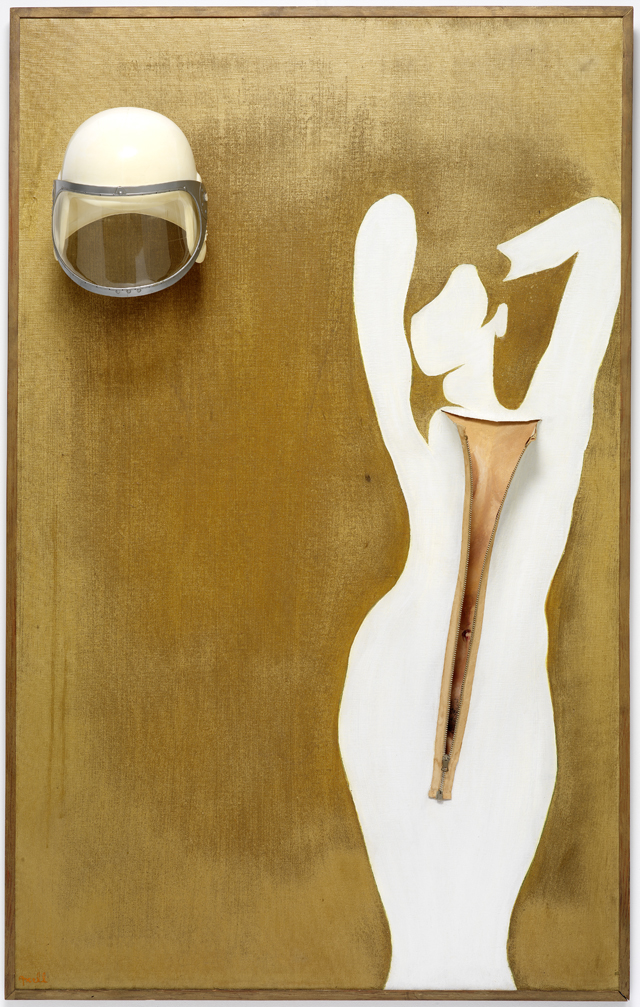

Bourgeois began the project by painting male and female torsos on paper; the gouache pigments are combined with water to give fluidity to the mixtures of red, blue and black. All the bodies are depicted in profile, in various positions, presenting delicate silhouettes that form the basis of the final works. These were then passed to Emin for embellishment, who reportedly cradled them like porcelain babies for months on end, until she finally saw beneath the surfaces of the mute bodies. Emin’s contribution consists of smaller figures drawn in pencil and the addition of occasionally coherent, hurriedly scratched out words. The idea is that Emin’s additions tease out the emotions, anxieties, ideas and histories that already lay dormant in Bourgeois’ paintings.

The works are elegant in form and colour; they are simple but playful, and tinged with a wry seriousness. The elegance derives from the delicate hues and the way they are loosely contained within soft lines, which accentuates the simplicity of bodies represented only in outline. The playfulness is in Emin’s characteristically childish scrawl, which sometimes seems unsure of how to respond to nudity so opts to make a joke of it. Come unto Me depicts a man lying on his back, with two miniature women kneeling at the base of his penis on which a third woman hangs on a cross. The serious message that women are subjugated to male sexuality is obscured by the humorous conception of the erect penis as a purely structural accessory to an ancient form of execution.

The forgoing theme is clearly a feminist agenda, and the result of both artists’ preoccupations. The relation between man and woman is characterised as one where the woman is locked in service to the man who rejects her pleas for love, thus having to accept the potency of his sexuality as a form of affection. And So I Kissed You offers a heartbreaking image of male sexual obsession while Just Hanging predicts emotional and physical death as a result of this servitude.

In other works, the female relation to child-bearing is explored as an experience of pain, personal loss and lingering failure. I Wanted to Love You More shows a female figure embedded within the pregnant bulge of a woman, expressing perhaps the desire of an embittered mother to get closer to her unwanted child. Reaching for You shows a woman who has burrowed into her own womb in order to retrieve a lost, perhaps aborted, child.

These are serious, and sometimes harrowing, themes. You get the feeling, however, that Bourgeois meant them to retain the autobiographical subtlety and integrity of artistic form that her meditations on her mother – the huge spider sculptures, titled Maman – possessed. As a child of surrealism, Bourgeois excelled in burying her neurosis under layers of symbolism and maintaining a visceral glee in the materiality of her art. But with Emin, there is no such thing: like in her neon pleas for love that shout desperation through the night sky or her bed that celebrates her frantic degeneracy, her contributions to these works drags the emotions to the surface and screams a blood-curdling cry. At this point of contrast between the two artists’ approaches, Emin begins to look tired, as if repeating her story in the same language of vulgarity is the only way she knows how, having never learned Bourgeois’ subtlety. It looks, then, as if Bourgeois’ invitation to collaboration is also an attempt at tutelage.

Nonetheless, the work derives its brilliance from the contrast between the collaborators, where Emin has mapped her own ideas on to Bourgeois’. If you couldn’t tell where Bourgeois ends and Emin begins, you would lose the sense that two individuals are trying to tell their own stories together precisely because their stories are so remarkably similar. In the end, Bourgeois is responsible for the aesthetic brilliance of these works, while Emin brings the emotions in. Combined, these two elements make a provocative show in which Bourgeois, at the end of her illustrious career, hands her mantel to Emin, securing both of their places in art history as experts in autobiographical art.”

Text By Daniel Barnes blogged from here

Text By Daniel Barnes blogged from here