“You can want one thing and have a secret wish for its opposite.” ― Deb Caletti, The Six Rules of Maybe

Author Archives: corporealfemme

doll clothes

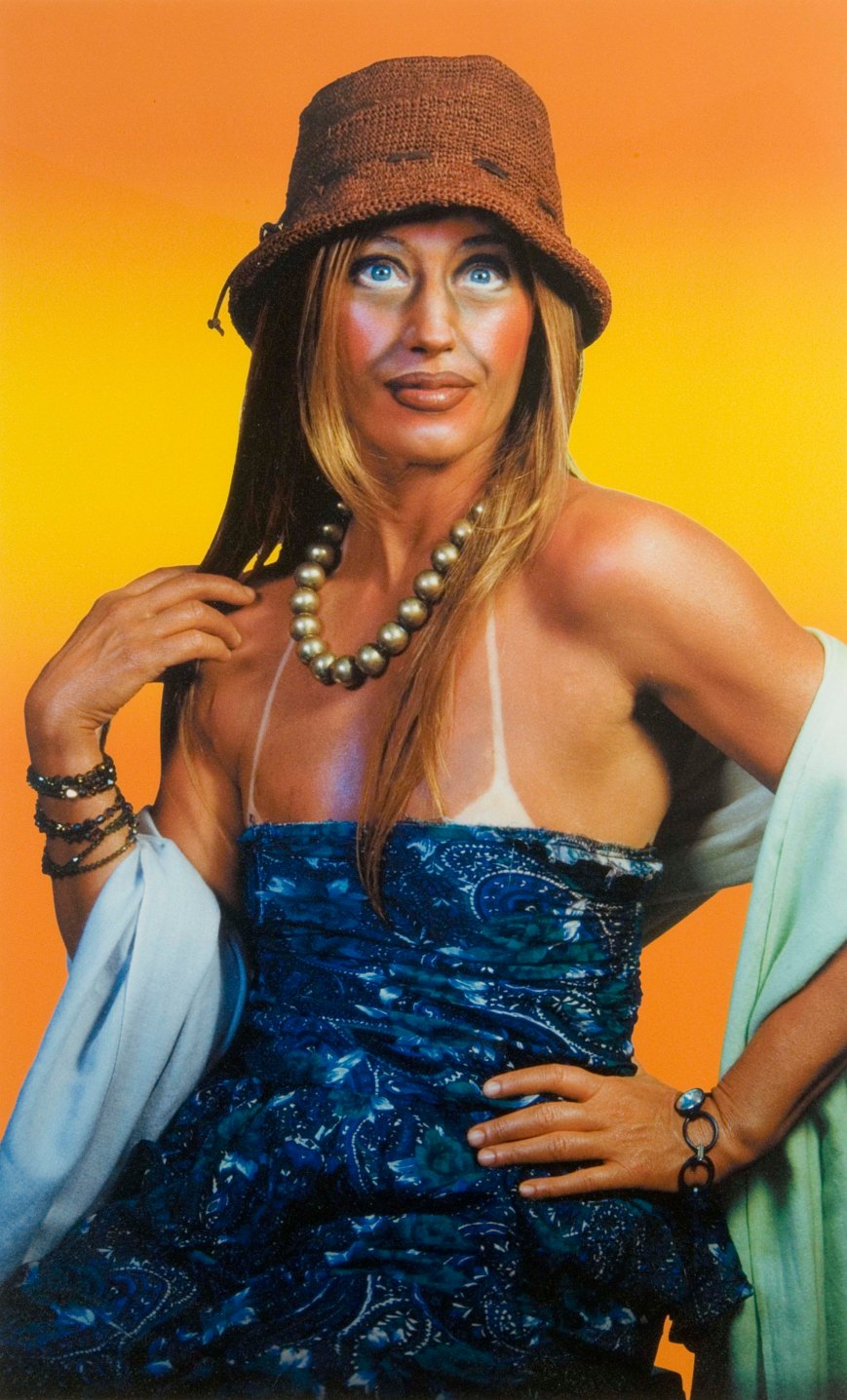

the art of the impersonator – photos by cindy sherman

“I feel I’m anonymous in my work. When I look at the pictures, I never see myself; they aren’t self-portraits. Sometimes I disappear.”

“Cindy Sherman has explored different kinds of photography, but she has become one of the most lauded artists of her generation for her photographs of her impersonations. Since she arrived on the scene, in a 1980 exhibition, when she was in her mid-twenties, she has come before her own camera in the guise of hundreds of characters, and as an impersonator—which in her case means being a creator of people, and sometimes people-like creatures, who we encounter only in a single photograph—she has been remarkably inventive. Especially as a portrayer of types of people, whether someone who appears to be a perky suburbanite in town for a matinee, or a woman in a sweatshirt who seems both tired and bristling, or a club singer belting out a note, Sherman—who is now, at fifty-eight, the subject of a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art—has shown herself as well to be a witty and shrewd social observer. And the sheer human spectacle of someone continually transforming herself into one person after another has proved riveting.”

“…Her various accessories and props are appealingly economical and rudimentary, and, given that her art is based on deception, one could say that her large photographs, which sometimes come with transparently cheesy frames, are meant to have the appearance of fake paintings. During much of the 1990s, she also experimented, in pictures she herself was not in, with close cropping and artificial, theatrical color and lighting. But none of this quite erased the way that her pictures in general, and certainly those in which she appears front and center in some disguise, often had the disembodied presence of blown-up shots from one kind of movie or another.”

“…Her various accessories and props are appealingly economical and rudimentary, and, given that her art is based on deception, one could say that her large photographs, which sometimes come with transparently cheesy frames, are meant to have the appearance of fake paintings. During much of the 1990s, she also experimented, in pictures she herself was not in, with close cropping and artificial, theatrical color and lighting. But none of this quite erased the way that her pictures in general, and certainly those in which she appears front and center in some disguise, often had the disembodied presence of blown-up shots from one kind of movie or another.”

“…The end result of Sherman’s many approaches is a roller coaster of discontent, at times recalling Otto Dix, at other moments Carol Burnett. Sherman can be reproachful and quietly barbed, or merely leaden and gloomy, or showily horrifying, or buoyantly nasty. The works that held me longest were of her strivers and her patronesses. They bring together the poles of Sherman’s thinking: her feeling for contemporary life and for the monstrous. We see people who, carefully but excessively made up, have turned their faces into masks. This can be said of her clowns as well, but they are so fully masked that we have little sense (as we have little sense with actual, professional clowns) of the person underneath the makeup.”

“More crucially, clowns, whether threatening or sad, are so familiar a theme that it is hard to put much stock in Sherman’s versions, which add little to the lore. With her overly avid women and her lionesses of the social scene, however, we feel we look, in each picture, at three people. There is Sherman herself, who, with her fair hair, pale eyebrows, and somewhat pointed features, resembles women in Memling portraits. Then there is her subject, who is clearly hidden behind a protective armor.”

“…Sherman isn’t the first artist to come before the camera in a series of disguises or impersonations. Surely no artist, though, has used the notion as a premise for an entire career, and it creates for her audience a rare sense of intimacy with her and suspense about where she will go next. We seem to look at someone who has indentured her very person for the sake of her art. We can believe we are in this strange lifelong adventure with her, and, especially if we are her age or older, we wonder a little apprehensively how she will handle the issue of aging.”

“…Sherman isn’t the first artist to come before the camera in a series of disguises or impersonations. Surely no artist, though, has used the notion as a premise for an entire career, and it creates for her audience a rare sense of intimacy with her and suspense about where she will go next. We seem to look at someone who has indentured her very person for the sake of her art. We can believe we are in this strange lifelong adventure with her, and, especially if we are her age or older, we wonder a little apprehensively how she will handle the issue of aging.” “…On the most literal level, though, we look at someone who has a gift for impersonation. Born in New Jersey and raised on Long Island, Sherman went to Buffalo State College in the early 1970s with the idea of becoming a painter. But she had been disguising herself as different people since childhood. There is a photo of her in the Modern’s catalog around age twelve in which, standing on a suburban street along with a friend who is also in masquerade, she appears convincingly as a little old lady. In college she was exposed to conceptual art, which, already supplanting painting as the field that art students wanted to work in, enabled her to see that she could build on her feeling for impersonation.”

“…On the most literal level, though, we look at someone who has a gift for impersonation. Born in New Jersey and raised on Long Island, Sherman went to Buffalo State College in the early 1970s with the idea of becoming a painter. But she had been disguising herself as different people since childhood. There is a photo of her in the Modern’s catalog around age twelve in which, standing on a suburban street along with a friend who is also in masquerade, she appears convincingly as a little old lady. In college she was exposed to conceptual art, which, already supplanting painting as the field that art students wanted to work in, enabled her to see that she could build on her feeling for impersonation.” read the whole article here

read the whole article here

lost beauty

NOTES TOWARDS A KIND OF TRANSCENDENCE

6.

…So much imprisoned beauty withers away.

And even the princesses shut away in their towers know that the arrival of prince charming is but

the prelude to spousal segregation, that what must be done is to abolish both the prisons and the

liberators at the same time, that what we need isn’t programs for liberation but practices of

freedom.

10 inch by marlene dumas

unica zurn by hans bellmer

the fury of god´s goodbye by anne sexton

One day He

tipped His top hat

and walked

out of the room,

ending the argument.

He stomped off

saying:

I don’t give guarantees.

I was left

quite alone

using up the darkness

I rolled up

my sweater,

up in a ball,

and took it

to bed with me,

a kind of stand-in

for God,

that washerwoman

who walks out

when you’re clean

but not ironed.

When I woke up

the sweater

had turned to

bricks of gold.

I’d won the world

but like a

forsaken explorer,

I’d lost

my map.

matriarch

we can’t live without us and we can’t live without them too

green pink caviar by marilyn minter

jabberwocky

the art of hannah wilke: ‘feminist narcissism’ and the reclamation of the erotic body

The politics of inclusion that shaped feminist discourse in the 1960s and 1970s spawned a legacy of body-based performance art, much of which was associated with women artists who used their own face as a subject of continual exploration. The self- imaging of women artists such as the provocative American artist Hannah Wilke was frequently attacked and dismissed by art critics as being indulgent exercises in narcissism that only served to reinforce the objectification of the female body. The charge of narcissism leveled on Wilke and her work may have been warranted, however, this should not be considered as a pejorative. Rather, the narcissism of Wilke can be viewed as a shrewd feminist tactic of self-objectification aimed at reclaiming the eroticized female body from the exclusive domain of male sexual desire. The ‘self-love’ of narcissism is a necessary component to this reclaiming of the body and the assertion of a female erotic will as being distinct from that of the male artist. Wilke wielded her narcissistic self-love as a powerful tool of critique, defiantly placing her own image into the hallowed halls of the male-dominated art institution.

The politics of inclusion that shaped feminist discourse in the 1960s and 1970s spawned a legacy of body-based performance art, much of which was associated with women artists who used their own face as a subject of continual exploration. The self- imaging of women artists such as the provocative American artist Hannah Wilke was frequently attacked and dismissed by art critics as being indulgent exercises in narcissism that only served to reinforce the objectification of the female body. The charge of narcissism leveled on Wilke and her work may have been warranted, however, this should not be considered as a pejorative. Rather, the narcissism of Wilke can be viewed as a shrewd feminist tactic of self-objectification aimed at reclaiming the eroticized female body from the exclusive domain of male sexual desire. The ‘self-love’ of narcissism is a necessary component to this reclaiming of the body and the assertion of a female erotic will as being distinct from that of the male artist. Wilke wielded her narcissistic self-love as a powerful tool of critique, defiantly placing her own image into the hallowed halls of the male-dominated art institution.

The term “narcissism” derives from the ancient Greek myth of Narcissus, a beautiful but arrogant youth who cruelly spurned the love of his admirers. For his cruelty, he was cursed by the goddess Nemesis and fell in love with his own reflection in a pool of water. The doomed Narcissus pined away for his unattainable lover – the image of his own self – and literally died as a result of his amorous longing.

Sigmund Freud bestowed the name of this mythic Greek youth upon his psychoanalytic theory of narcissism, a theory that describes normal personality development. According to Freud, the self-love of narcissism is a normal complement to the development of a healthy ego. Whereas a certain amount of narcissism is desirable, an excess of self-love is considered dysfunctional and indicative of pathology. This latter definition of narcissism, the one of pathological self-absorption, has cast our current understanding of narcissism in a negative light and reinforced the use of the term as a pejorative.

The psychoanalytic theories of Freud suggest that negative or pathological narcissism is a specifically female perversion. Art critic Amelia Jones writes that “[d]rawing loosely on Freud’s definitions – which connect narcissism to both a stage of development and to a form of homosexual neurosis – narcissism has come in everyday parlance to mean simply a kind of “self-love” epitomized through woman’s obsession with her own appearance.” Hence, the charges of narcissism leveled on Hannah Wilke were attempts by the critics to summarily dismiss her work as mere manifestations of a woman’s obsessive self-love and infer, according to Jones, that Wilke’s art was not “successfully feminist.”

Continue reading here

red flag by judy chicago, 1971

by margaret bertulli

I bleed

I bleed and I wonder

“Will this be the last time?”

I bleed, therefore I am

“What will it be like?

This cessation of menses?”

The unequivocal end of child-bearing.

And my womb, though childless,

Will it feel the end of possibility?

Perhaps.

And then the unforeseen strength,

Promised by gender and age, will come.

The sureness, the wisdom,

The spirit to sing my songs.

I know this as all women before me have known.

We know this as we smile at the moon

Adrienne Rich

“A thinking woman sleeps with monsters

that beak which grips her, she becomes.”

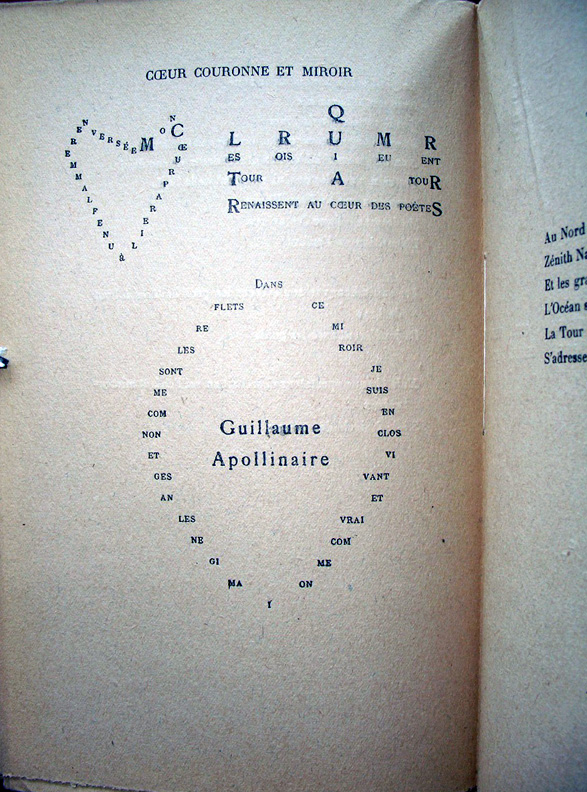

calligramme by apollinaire

sound poetry by kurt schwitters

I accidentally opened two browsers, both playing this video. One started slightly before the other. Having two playing at once enhances the poetry beautifully.

`it is necessary for poetry to discard language´

Cabaret Voltaire, Zurich, 1916. Wearing a cardboard costume of blue, scarlet and gold, Hugo Ball is carried to the stage in darkness. As the lights go up, the audience of Swiss bourgeoisie, artists, intellectuals, and refugees from the carnage of WWI, is silent. Ball begins a priestly incantation: ‘gadji beri bimba glandridi laula lonni cadori gadjama gramma berida bimbala glandri galassassa laulitalomini…’. The place to be, Spiegelgasse 1: simultaneous sound poems, noise music, ‘primitivist’ chants and drums, masked dancers, the absurd, the irrational, improvisation, chance, confrontation and cacophony. The lights dim. The audience responds with bewilderment and rage, and Ball disappears into the darkness. ‘It is necessary for poetry to discard language’, he writes, ‘as painting has discarded the object’.

Cabaret Voltaire, Zurich, 1916. Wearing a cardboard costume of blue, scarlet and gold, Hugo Ball is carried to the stage in darkness. As the lights go up, the audience of Swiss bourgeoisie, artists, intellectuals, and refugees from the carnage of WWI, is silent. Ball begins a priestly incantation: ‘gadji beri bimba glandridi laula lonni cadori gadjama gramma berida bimbala glandri galassassa laulitalomini…’. The place to be, Spiegelgasse 1: simultaneous sound poems, noise music, ‘primitivist’ chants and drums, masked dancers, the absurd, the irrational, improvisation, chance, confrontation and cacophony. The lights dim. The audience responds with bewilderment and rage, and Ball disappears into the darkness. ‘It is necessary for poetry to discard language’, he writes, ‘as painting has discarded the object’.

dada manifesto by hugo ball, zurich, july 14, 1916.

Dada is a new tendency in art. One can tell this from the fact that until now nobody knew anything about it, and tomorrow everyone in Zurich will be talking about it. Dada comes from the dictionary. It is terribly simple. In French it means “hobby horse”. In German it means “good-bye”, “Get off my back”, “Be seeing you sometime”. In Romanian: “Yes, indeed, you are right, that’s it. But of course, yes, definitely, right”. And so forth.

An International word. Just a word, and the word a movement. Very easy to understand. Quite terribly simple. To make of it an artistic tendency must mean that one is anticipating complications. Dada psychology, dada Germany cum indigestion and fog paroxysm, dada literature, dada bourgeoisie, and yourselves, honoured poets, who are always writing with words but never writing the word itself, who are always writing around the actual point. Dada world war without end, dada revolution without beginning, dada, you friends and also-poets, esteemed sirs, manufacturers, and evangelists. Dada Tzara, dada Huelsenbeck, dada m’dada, dada m’dada dada mhm, dada dera dada, dada Hue, dada Tza.

How does one achieve eternal bliss? By saying dada. How does one become famous? By saying dada. With a noble gesture and delicate propriety. Till one goes crazy. Till one loses consciousness. How can one get rid of everything that smacks of journalism, worms, everything nice and right, blinkered, moralistic, europeanised, enervated? By saying dada. Dada is the world soul, dada is the pawnshop. Dada is the world’s best lily-milk soap. Dada Mr Rubiner, dada Mr Korrodi. Dada Mr Anastasius Lilienstein. In plain language: the hospitality of the Swiss is something to be profoundly appreciated. And in questions of aesthetics the key is quality.

I shall be reading poems that are meant to dispense with conventional language, no less, and to have done with it. Dada Johann Fuchsgang Goethe. Dada Stendhal. Dada Dalai Lama, Buddha, Bible, and Nietzsche. Dada m’dada. Dada mhm dada da. It’s a question of connections, and of loosening them up a bit to start with. I don’t want words that other people have invented. All the words are other people’s inventions. I want my own stuff, my own rhythm, and vowels and consonants too, matching the rhythm and all my own. If this pulsation is seven yards long, I want words for it that are seven yards long. Mr Schulz’s words are only two and a half centimetres long.

It will serve to show how articulated language comes into being. I let the vowels fool around. I let the vowels quite simply occur, as a cat meows … Words emerge, shoulders of words, legs, arms, hands of words. Au, oi, uh. One shouldn’t let too many words out. A line of poetry is a chance to get rid of all the filth that clings to this accursed language, as if put there by stockbrokers’ hands, hands worn smooth by coins. I want the word where it ends and begins. Dada is the heart of words.

Each thing has its word, but the word has become a thing by itself. Why shouldn’t I find it? Why can’t a tree be called Pluplusch, and Pluplubasch when it has been raining? The word, the word, the word outside your domain, your stuffiness, this laughable impotence, your stupendous smugness, outside all the parrotry of your self-evident limitedness. The word, gentlemen, is a public concern of the first importance.

one morning by jamie heckert, 2006

One morning, not that long ago, I answered the door in my dressing gown

to the sight of a man from the energy company. He came to ask me why I had

chosen to switch suppliers. As I explained that I preferred one with a better

environmental policy, I slowly realised that not only did this guy have gorgeous

eyes, he was watching me closely. I went on to say, performing a bit for this

beautiful man, “Of course all corporations and really capitalism in general is bad

for the environment”. He agreed, his eyes glowing with excitement. But, what

could he do? He had a mortgage to pay. I’m not quite sure why, maybe I was

scared of the intensity of my attraction, but suddenly I found myself channeling

some broken record of anarchist propaganda and said, “We need resistance on

the inside, too.” That was it. His beautiful eyes looked away and the connection

was lost.

I feel grief remembering that morning; I would have liked to have listened

with empathy to both his desire for change and for security, to maintained that

beautiful sense of connection. Instead, I tried to recruit him. When I replay the

incident in my mind, it has a different ending. I ask him, “What would you like

to do?”

camus on desire

What distinguishes consciousness of self from the world of nature is not the simple act of contemplation by which it identifies itself with the exterior world and finds oblivion, but the desire it can feel with regard to the world. This desire re-establishes its identity when it demonstrates that the exterior world is something apart. In its desire, the exterior world consists of what it does not possess, but which nevertheless exists, and of what it would like to exist but which no longer does. Consciousness of self is therefore, of necessity, desire. But in order to exist it must be satisfied, and it can only be satisfied by the gratification of its desire. It therefore acts in order to gratify itself and, in so doing, it denies and suppresses its means of gratification. It is the epitome of negation.

from The Rebel

nietzsche on the hard

“Why so hard?” the kitchen coal once said to the diamond. “After all, are we not close kin?” Why so soft? O my brothers, thus I ask you: are you not after all my brothers? Why so soft, so pliant and yielding? Why is there so much denial, self-denial, in your hearts? So little destiny in your eyes? And if you do not want to be destinies and inexorable ones, how can you one day triumph with me? And if your hardness does not wish to flash and cut through, how can you one day create with me? For all creators are hard. And it must seem blessedness to you to impress your hand on millennia as on wax. Blessedness to write on the will of millennia as on bronze — harder than bronze, nobler than bronze. Only the noblest is altogether hard. This new tablet, O my brothers, I place over you: Become hard!

— Zarathustra, III: On Old and New Tablets, 29.

process: immaterial proposal by christine eyene

man ray

not enough love

buskers, edinburgh

highgate cemetery

yoko

Oh, please don’t give me that!

Yes, I’m a witch,

I’m a bitch

I don’t care what you say,

My voice is real.

My voice speaks truth,

I don’t fit in your ways.

I’m not gonna die for you,

You might as well face the truth,

I’m gonna stick around for quite awhile.

We’re gonna say,

We’re gonna try,

We’re gonna try it our way.

We’ve been repressed,

We’ve been depressed,

Suppression all the way.

We’re not gonna die for you,

We’re not seeking vengeance,

But we’re not gonna kill ourselves for your convenience.

Each time we don’t say what we wanna say, we’re dying.

Each time we close our minds to how we feel, we’re dying.

Each time we gotta do what we wanna do, we’re living.

Each time were open to what we see and hear, we’re living.

We’ll free you from the ghettos of your minds,

We’ll free you from your fears and binds,

We know you want things to stay as it is,

It’s gonna change, baby.

It’s gonna change, baby doll,

It’s gonna change, honey ball,

It’s gonna change, sugar cane,

It’s gonna change, sweetie legs.

So don’t try to make cock-pecked people out of us.

no regard