1997. Video installation, two overlapping projections (color, sound with Anders Guggisberg), Dimensions variable. Fractional and promised gift of Donald L. Bryant, Jr. © Pipilotti Rist

Category Archives: film

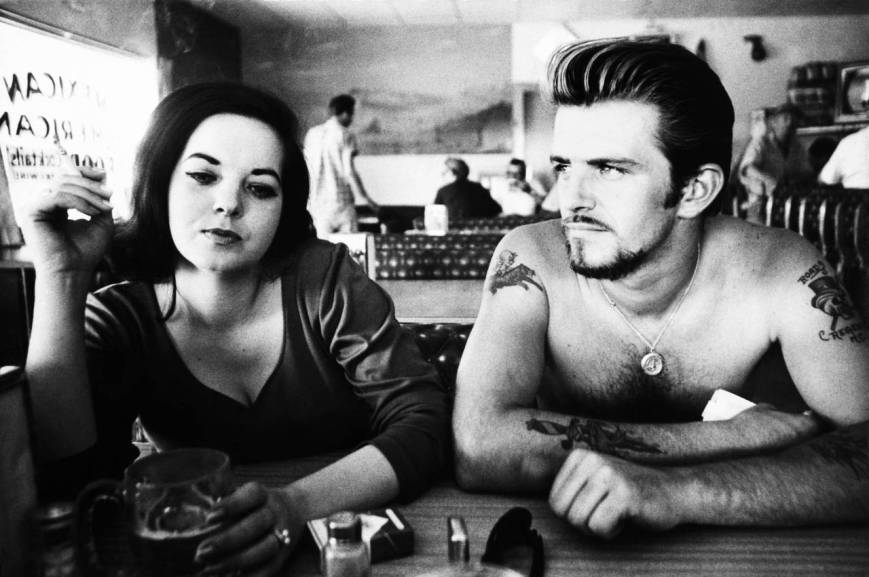

sugarman’s been found

I’ve never seen the entire audience at a movie theatre sit through all the titles at the end, until I saw Searching for Sugarman a couple of nights ago. The film had been showing at Rosebank’s Cinema Nouveau for months – the first time I went to see documentary it was chock-full – but, incredibly, there was still a sizeable collection of people gathered to pay homage to Sixto “Jesus” Rodriguez..

The story of how Rodriguez, who lived in complete obscurity in his Detroit home in the US, and was “found” by two South African fans more than 25 years after his albums were released, has a fairy-tale quality to it. This is – apart from the fact that it’s a great documentary – no doubt why it has received numerous awards and critical acclaim across the globe.

The singer is not only a huge talent, but also a genuinely humble, nice guy, so he was able to quietly step into the role of long-lost hero with style and aplomb in the one country that reveres his music. This was in total contrast to his fans, who, when he finally appeared onstage in 1998, screamed without stopping for around frenzied 10 minutes, before he was finally able to sing his first song.

To give an outsider an idea of what Rodriguez meant to so-called white South Africans, he apparently sold half a million albums here (for which he received, I believe, no royalties). There are only four or five million so-called whites in this country, which means around one in 10 of them must have bought his music since 1971, when his albums came out.

And that’s not counting the countless others who taped the albums back in the days of cassettes. And if you also factor in how many whities heard his music from people who bought or taped it, it means practically an entire generation heard and grew up on his songs. He is part of our collective psyche, and is probably the most influential artist on white South African consciousness of the last quarter of the last century.

For those who weren’t here back in the bad old days, Malik Bendjelloul’s documentary explains pretty clearly, through interviews with South Africans, just why Rodriguez’s lyrics had such a massive, profound impact on those living under the oppression of apartheid. Many of his songs were banned, and never made it onto the radio, all of which merely encouraged people to acquire them.

I don’t want to give away too much, because this is a movie I think everyone should see, whether one hails from South Africa or not. It’s a universal theme, and it happens that every now and then that late in an artist’s life someone discovers their art in some other country, a la Buena Vista Social Club, or he or she discovers they are ‘big in Japan’ just when they were thinking of giving up on their art. Many South African artists only ‘made it’ in their own country when they returned from successful tours overseas.

And in the case of Rodriguez there’s the added irony that he isn’t ‘white’ at all – he’s the product of American Indian and Mexican parentage. Most white army conscripts’ musical collections in the 80s, I recall, were well stocked with Rodriguez and Bob Marley, both of whom conveyed messages entirely antithetical war and racism. Did the conscripts, rocking to these grooves in the heat of the Angolan or Namibian sun, know this at a conscious, or at some deeper level?

I guess no one will ever know. What I know for sure is that I am going to see Rodriguez’s fifth South African concert next year. Sugarman is still sweet music to my ears.

g g allin – hated

documentary by: Todd Philips

I sometimes listen to GG Allin,but i can never take it too serious. This documentary however is amazing. Warning:explicit content

shocking! the real purpose of your life!

And you thought you knew! Produced by Trey Parker and Matt Stone.

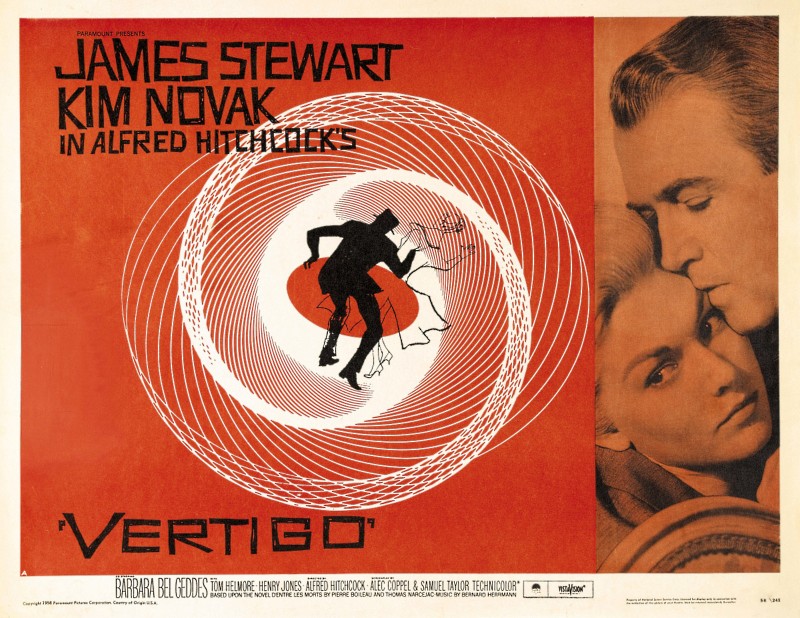

vertigo

Cape Town’s Good Film Society presents this Alfred Hitchcock masterpiece, on at the Labia Theatre at 20h15 tonight.

Recently voted in Sight and Sound’s definitive poll as the greatest film ever made (the only film to surpass Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane in many a decade), come to this Sunday’s one-off screening and decide for yourself if it’s worthy of the accolade!

Vertigo is the spellbinding tale of an ex-policeman with a fear of heights, Scottie Ferguson (James Stewart), who is hired by an old friend to investigate his wife (Kim Novak). But it’s no ordinary case – the woman is suspected of being possessed by the malignant spirit of a suicide victim. As the mystery leads to a spiral into paranoia and obsession, Scottie is forced to encounter the most painful truth: He has fallen in love with a woman who may not exist. Stylistically breathtaking, intellectually complex and profound, the film is a startlingly experimental exploration of desire, a psychological spider-web woven with unusual compassion by the master of nightmares. With this touchstone of psychological thrillers – his most personal masterpiece – Hitchcock defined not only a genre, but an entire era of filmmaking and art. Continue reading

alice (jan svankmajer, 1988)

In Alice, a little girl follows a white rabbit into a world where nothing is quite what it seems. Where Czech surrealist Švankmajer’s Alice differs from other adaptations of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland is that it explores the book’s darker side as well, thereby remaining faithful to the tone of uneasy confusion that pervades the original story. A live-action Alice (Kristyna Kohoutova) inhabits a Wonderland that teems with threatening stop-motion characters. Švankmajer’s visual canniness and piercing psychological insight permeate the film with a menacing dream-logic. Curiouser and curiouser.

alice in wonderland (w. w. young, 1915)

W. W. Young’s 1915 film of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. Starring Viola Savoy as Alice. Produced by The American Film Manufacturing Company (Flying A Studios) and released on 19 January 1915.

alice in wonderland (hepworth/stow, 1903)

Directed by two of the founders of British cinema, Cecil Hepworth and Percy Stow, its original running time of twelve minutes made the first cinematic adaptation of Lewis Carroll’s literary classic the longest running British film to date.The one remaining print has been restored by the BFI, and here it is, courtesy of Youtube.

Alice in Wonderland was clearly made for cinema goers who had already read the book, hence describing this version of Alice in Wonderland as a literary adaptation in the modern understanding of the term may be misleading (without prior knowledge of the books, deciphering the events of the film would be quite difficult). Given the film’s length, it would be better to describe it as a series of vignettes from the book. It is perhaps this aspect of the film’s organisation that gives it a peculiar and slightly disjointed feel.

It is memorable for its use of special effects, clearly inspired by the likes of Georges Méliès and the Lumière Brothers.

Despite the BFI’s best efforts, the original reel of Alice in Wonderland was damaged to such an extent that the deterioration is quite clearly visible on the restored print. This however, only heightens the dreamlike atmosphere of the film. Combined with the fact that the film is not a ‘conventional narrative’, Alice in Wonderland can be seen as a forerunner for the works of surrealist filmmakers such as René Clair, Luis Buñuel and Jean Cocteau.

Read more about the film HERE.

the unnamable (1999)

A film by Jenny Triggs, based on the novel of the same name by Samuel Beckett. This film animates body parts, chess pieces and mechnical motifs as life’s conveyor belt threatens to grind to a halt, but never does.

Contact jenny.triggs@blueyonder.co.uk for further information.

the breeders – wicked little town

Beautiful cover version from Wig In A Box – Songs From And Inspired By Hedwig And The Angry Inch (2003).

fire in my belly

Fire in My Belly (1987): David Wojnarowicz

Music: Diamanda Galas

Made by David Wojnarowicz for Rosa von Praunheim’s Silence = Death (1990).

A positive diagnosis for HIV in 1987 didn’t leave you with many options. The pharmaceuticals that have extended life spans for many of those now infected were not then available. Hostility and fear were rampant. It was reasonable to assume not only that you had received a death sentence, but that there was no hope on the horizon for those who, inevitably, would follow in your footsteps: an anguished decision to be tested, an excruciating wait for the results, a terrifying trip to the testing centre, and a life-shattering conversation with a grim-faced nurse or social worker.

Some turned to holistic medicine and yoga. Others to activism. Many just returned to their apartments, curled up in the corner, and waited to die.

But some, like David Wojnarowicz, who died in 1992 at the age of 37, used art to keep a grip on the world. He was the quintessential East Village figure, a bit of a loner, a bit crazy, ferociously brilliant and anarchic. He was a self-educated dropout who made art on garbage can lids, who painted inside the West Side piers where men met for anonymous sex, who pressed friends into lookout duty while he covered the walls of New York with graffiti. In 1987, his former lover and best friend, Peter Hujar, died of complications from AIDS, and Wojnarowicz learned that he, too, was infected with HIV.

Wojnarowicz, whose video A Fire in My Belly was removed from an exhibition of gay portraiture at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery last week after protests from a right-wing Catholic group and members of Congress, was an artist well before AIDS shattered his existence. But AIDS sharpened his anger, condensed his imagery and fueled his writing, which became at least as important as his visual work in the years before he died. In the video that has now been censored from the prominent and critically lauded exhibition Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture, Wojnarowicz perfectly captured a raw Gothic, rage-filled sensibility that defined a style of outsider art that was moving into the mainstream in the late 1980s.

It may feel excessive now, but like other classic examples of excessive art – Allen Ginsberg’s 1955 poem, Howl, Krzyzstof Penderecki’s 1960 symphonic work, Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima, or Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1975 film, Salo – it is an invaluable emotional snapshot. Not simply a cry of anguish or protest, Wojnarowicz’s work captures the contradiction, speed and phantasmagoria of a time when it was reasonable to assume that all the political and social progress gay people had achieved in the 1960s and ’70s was being revoked – against the surreal, Reagan-era backdrop of Morning in America, and a feel-good surge of American nostalgia and triumphalism.

Read more of this 2010 article by Philip Kennicott, from the Washington Post, HERE.

songs from the second floor (sweden, 2000)

This poetic, surrealistic and disturbing Swedish film – sometimes called a “black comedy” – written and directed by Roy Andersson, received a number of awards, including the Swedish Film Critics Award and the Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival. It makes use of many quotations from the work of the Peruvian poet César Vallejo. It’s like a multiple pile-up where Vallejo is crashed into by Beckett, tail-ended by Bergman… and Monty Python can’t slow down or swerve enough to avoid sandwiching them all together.

Reviewed by Anton Bitel:

“Everything has its day,” says the CEO Lennart (Bengt CW Carlsson), concealed (but for his bare feet) beneath a sunbed, to his flustered sub-manager Pelle (Torbjörn Fahlström) in the opening scene of Roy Andersson’s Songs From The Second Floor. “This is a new day and age, Pelle – you have to realise that.” Faced with the imminent collapse of his business empire and the mass unemployment that will inevitably result, this invisible mogul has already decided to take the money and run, contemplating a better life (or should that be afterlife?) abroad for himself in the future once he has put the past behind him. With blithe disregard for those that he is abandoning, he asks, “What’s the point of staying where there is only misery?” – and yet Andersson’s film offers a dystopian vision of the new millennium, where misery, pain, guilt and despair are the universal condition, where escape is impossible, and where, no matter how much anyone tries to turn their back on the past, somehow it always returns.

If everything has its day, the Songs From The Second Floor was certainly a long time in coming. Andersson first discovered the avant-garde Peruvian poet César Vallejo (19892-1938) back in 1965, and first read his poem Stumble Between Two Stars while working on his second feature Gilliap (1975). In the early Eighties he began preparations for a documentary feature based around the poem, before concluding that the material would be better served by the medium of fiction. So he established an independent film studio in 1981, and devoted the next 15 years of work (in short films and commercials) to inventing and honing an aesthetic style that would make his unique vision for this third feature possible. Production proper began in 1996, and lasted four long years – but the results were well worth the wait, and would indeed win the Swedish writer/director a slew of international awards.

The film is told in a series of stylised, hyperreal tableaux, unfolding in indifferent wideshot before an unmoving camera whose very distance helps convert all the tragedy of human experience on display into a very singular brand of dark comedy. Hence the mannered grey makeup worn by the performers – for while this may reflect their status as spiritual zombies lost to their own moral damnation, it is also the familiar mask of clowns, and all these characters are both the living dead and comic chumps. So it is that when, in one sequence, a stage magician (Lucio Vucina) accidentally saws into the belly of his hapless volunteer (Per Jörnelius), eliciting immediate cries of pain, we share the fictive audience’s initial instinct to laugh, even as we are horrified.

Some of the film’s episodes are self-contained vignettes, while others feature an ensemble of recurring characters in the orbit of Kalle (Lars Nordh). Having just torched his own furniture business, this corpulent, middle-aged salesman must deal with sceptical insurance adjusters and find a new outlet (viz. crucifixes) for his flagging spirit of entrepreneurship, even as a strong sense of guilt, both personal and collective, keeps creeping up on him.

Meanwhile Kalle’s eldest son, the poet Thomas (Peter Roth), suffers in silence in a mental institution, leaving his sensitive younger brother Stefan (Stefan Larsson) to pick up the pieces and hear the depressed confessions of passengers in his taxi cab. In the background of all this grief and anxiety, Andersson reveals a grimly absurd vista of societal breakdown, where acts of racist violence go unchecked, traffic jams go on forever, suited flagellants mortify themselves in the street, the dead walk among the (almost) living, panicking financiers resort to crystal balls, and a virgin is publicly sacrificed in a last-ditch effort to fend off not just economic ruin but the end of days.

“Beloved be the ones who sit down,” reads on-screen text near the beginning of Songs From The Second Floor, cited from Vallejo’s Stumble Between Two Stars – and it will recur, along with other lines from the poem, several times within the film itself. At first there might seem little room for poetry in Andersson’s nightmarish picture of a venal, gloomy and bleakly prosaic metropolis whose only poet, Thomas, whether driven mad by his work or by the world, has been reduced to inarticulate muteness.

And yet, like the ghosts of the dead that continue to haunt Kalle’s heavy conscience, or like the buried Nazi past of the superannuated general (Nils-Åke Olsson) that resurfaces in a torrent of Tourette’s-style outbursts (à la Dr Strangelove), poetry just keeps coming back. Even in a setting as banal as a commuter train, Andersson’s drab characters are apt to burst into choral song (magisterially scored by none other than ABBA’s Benny Andersson).

Much of the film’s poetic humanism derives from the word ‘beloved’ that forms a refrain in Vallejo’s poem. For while Andersson may offer up a monstrous parade of vices and vulnerabilities, he invites us to love his gallery of rogues precisely for the flaws that make them – and all of us – so human. A key, repeating image in the film is of different characters perched on the end of their beds, making each and every one of them “the ones who sit down” – but it is a phrase that rather pointedly describes any viewer as well, ensconced in cinema or on sofa. After all, Andersson’s story of frailty and folly is our story too – and at the end of the extraordinary 10-minute single take that closes Songs From The Second Floor, the look that Kalle gives straight to camera implicates us all in the film’s haunting return of the repressed.

Put simply, the everyday apocalypse envisaged in Songs From The Second Floor is a wonder to behold, an idiosyncratic humanist allegory without parallel in cinema – unless, of course, you include Andersson’s equally astonishing follow-up You, The Living (2007), with which it forms the first two parts of a projected trilogy on the “inadequacy of man”.

Directed and written by: Roy Andersson

Director of Photography: István Borbás, Jesper Klevenås

Music: Benny Andersson

This review was first published HERE.

die wonderwerker

Trailer for the new Katinka Heyns film Die Wonderwerker, based on the life of poet, lawyer, naturalist and morphine addict, Eugene Marais.

Released: 7th September 2012

Starring: Cobus Rossouw, Marius Weyers, Sandra Kotze, Dawid Minnaar, Elize Cawood, Anneke Weidemann, Kaz McFadden, Erica Wessels

Synopsis:

Eugene Marais was not only a remarkable poet and naturalist, but an extraordinary person whose life was a continuous source of drama and controversy. In 1908, he is a qualified lawyer who has just spent a solitary 2 years living amongst the baboons of the remote Waterberg; studying their habits.

On his way to Nylstroom, in the grip of a Malaria induced fever, he stops on a farm looking for drinking water. Observing his weakness and the seriousness of his illness, Gys van Rooyen and his wife Maria take him into their home to recover.

Maria leads an unfulfilled life and she is lonely. The forty year old Eugene Marais is attractive, charming and mysterious. She, as many women before her, falls in love with him. There are two others resident in the house, the Van Rooyen’s son Adriaan, and a seventeen year old adopted daughter Jane Brayshaw.

Twelve years earlier Marais’ young wife, Aletta, died giving birth to their only child, something he was never able to process. Jane is a striking embodiment of her. Gradually he realizes he is losing his heart to her. And she reciprocates. What further complicates matters is that the young Adriaan is himself smitten with Jane.

Eugene Marais’ secret demon is his morphine addiction. He is a high functioning addict- whose behaviour is only affected when he doesn’t use it. Maria discovers his secret. In an attempt to not only curb his addiction but also to assert control over him, she confiscates his morphine and begins rationing it back to him.

This leads to a love quadrangle, like a time bomb ticking. Inevitably ticking…

This Film is in Afrikaans with English subtitles.

marie menken – arabesque for kenneth anger (1961)

“There is no why for my making films. I just liked the twitters of the machine, and since it was an extension of painting for me, I tried it and loved it. In painting I never liked the staid and static, always looked for what would change the source of light and stance, using glitters, glass beads, luminous paint, so the camera was a natural for me to try—but how expensive!” – Marie Menken

16mm, color, sound, 4 min

Original score by Teiji Ito. “A new sound version of this classic. It is a beautiful experience to see her fabulous shooting. The cutting is just as fabulous and is something for all to study; the new score by Teiji Ito is ‘out of this world’ with its many-leveled instrumentation. Marie says ‘These animated observations of tiles and Moorish architecture were made as a thank-you to Kenneth for helping to shoot on another film in Spain.’ Shot in the Alhambra in one day.” – Gryphon Film Group

my autumn’s done come (letter to romy)

Based on the unfinished film by Henri George Clouzot, L’Enfer” (Inferno), with the beautiful Romy Schneider. Music by Lee Hazlewood.

no smoking

end of the century – the story of the ramones

tomorrow is a drag

Philippa Fallon performs the nihilistic beat poem ‘High School Drag’ aka ‘The Big Switch’ in High School Confidential (1958).

“Tool a fast shore, swing with a gassy chick.

Turn on to a thousand joys.

Smile on what happened, or check what’s going to happen,

You’ll miss what’s happening.

Turn your eyes inside and dig the vacuum.”

monty python – “french subtitled film”

Monty Python’s Flying Circus sketch from Season 2, Episode 10; first aired 1 December 1970; recorded 2 July 1970.

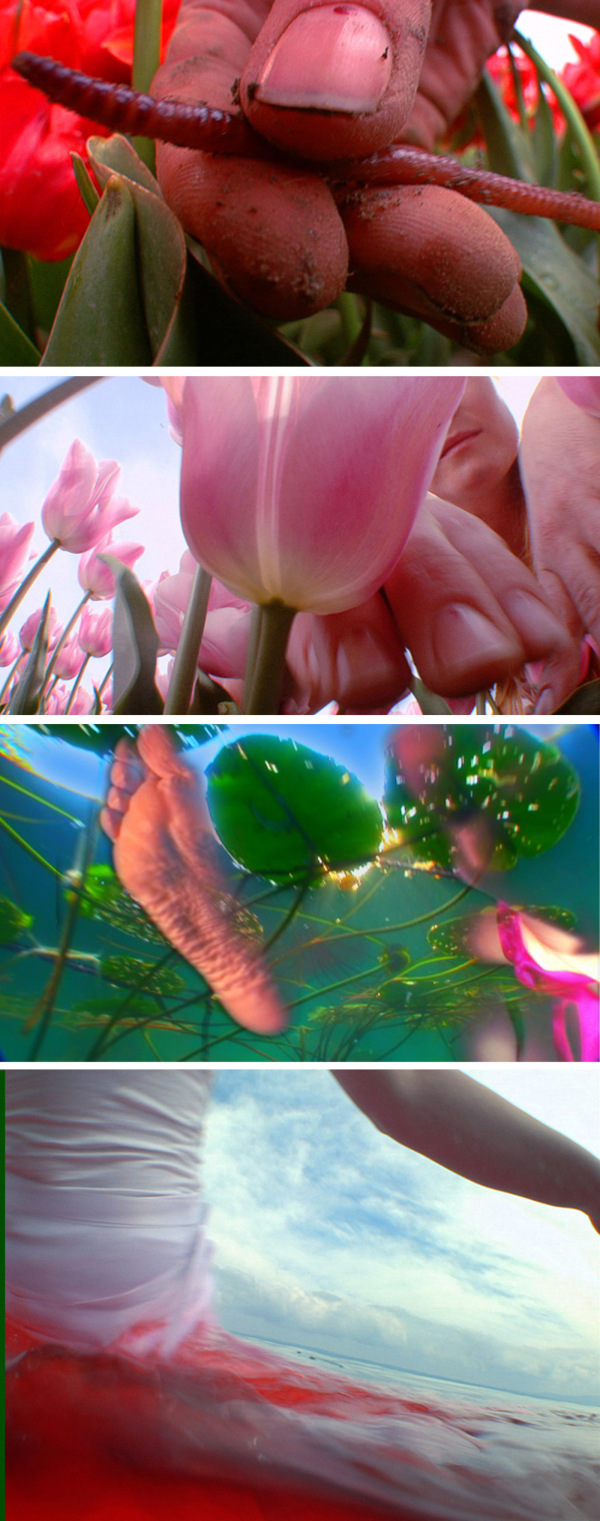

still from pour your body out (7354 cubic meters), by pipilotti rist

you killed me first!

Richard Kern with Lung Leg, 1985.

kodoma

Princess Mononoke is a period drama set in the late Muromachi period of Japan but with numerous fantastical elements. The story concentrates on involvement of the outsider Ashitaka in the struggle between the supernatural guardians of a forest and the humans of the Iron Town who consume its resources. There can be no clear victory, and the hope is that relationship between humans and nature can be cyclical.

“Mononoke” (物の怪) is not a name, but a general term in the Japanese language for a spirit or monster. The film was first released in Japan on July 12, 1997, and in the United States on October 29, 1999.

blue velvet (1986)

Song: Roy Orbison – Candy Colored Clown

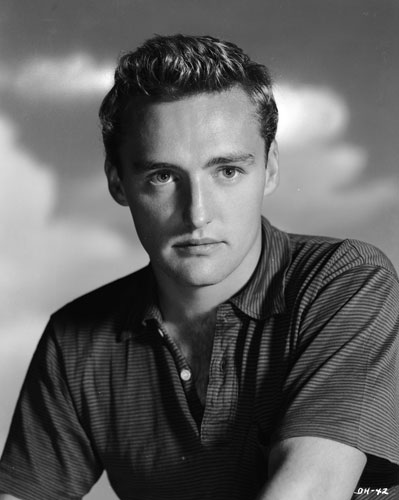

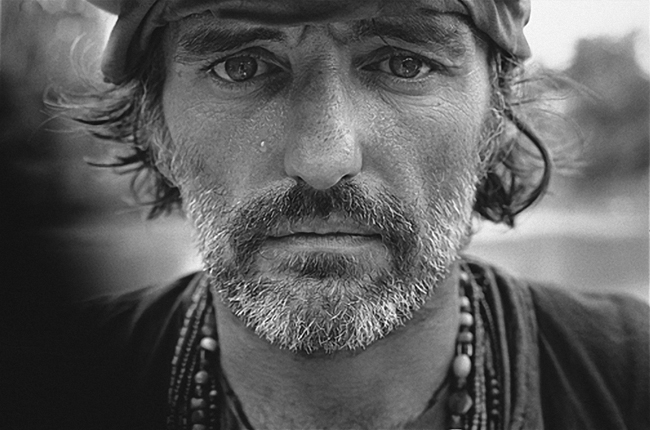

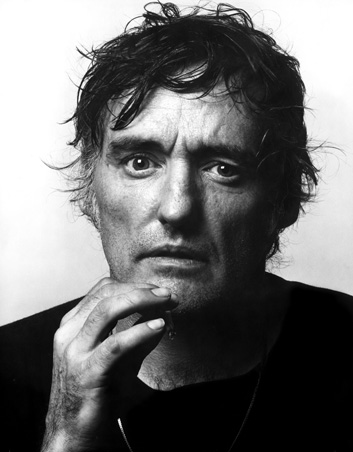

dennis hopper

Here I was, planning a nice, lengthy post about Marjorie Cameron and her art. What an amazing woman/artist/actress/occultist/ collaborator. While searching all kinds of wonderful material I came across Curtis Harrington’s 1961 psychological thriller “Night tide” where Cameron plays the Water Witch alongside Dennis Hopper (great stuff, great jazz.) Thing is, I got totally distracted by images of Dennis Hopper. <3

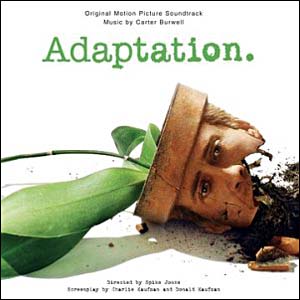

remixed from “adaptation” (2002)

JOHN LAROCHE:

JOHN LAROCHE:

You know why I like plants?

SUSAN ORLEAN:

Nuh uh.

JOHN LAROCHE:

Because they’re so mutable. Adaptation is a profound process. Means you figure out how to thrive in the world.

SUSAN ORLEAN:

[pause] Yeah but it’s easier for plants. I mean they have no memory. They just move on to whatever’s next. With a person though, adapting’s almost shameful. It’s like running away.

___

CHARLIE KAUFMAN: [voice-over]

I am pathetic, I am a loser…

ROBERT MCKEE:

So what is the substance of writing?

CHARLIE KAUFMAN: [voice-over]

I have failed, I am panicked. I’ve sold out, I am worthless, I… What the fuck am I doing here? What the fuck am I doing here? Fuck. It is my weakness, my ultimate lack of conviction that brings me here… And here I am because my jump into the abysmal well – isn’t that just a risk one takes when attempting something new? I should leave here right now. I’ll start over. I need to face this project head on and…

ROBERT MCKEE:

…and God help you if you use voice-over in your work, my friends. God help you. That’s flaccid, sloppy writing. Any idiot can write a voice-over narration to explain the thoughts of a character.

___

SUSAN ORLEAN:

There are too many ideas and things and people. Too many directions to go. I was starting to believe the reason it matters to care passionately about something, is that it whittles the world down to a more manageable size.

___

SUSAN ORLEAN:

Do you ever get lonely sometimes, Johnny?

JOHN LAROCHE:

Well, I was a weird kid. Nobody liked me. But I had this idea. If I waited long enough, someone would come around and just, you know… understand me. Like my mom, except someone else. She’d look at me and quietly say: “Yes.” Just like that. And I wouldn’t be alone anymore.

___

CHARLIE KAUFMAN:

There are no rules, Donald. And anyone who says there are is just, you know…

DONALD KAUFMAN:

Not rules, principles. McKee writes that a rule says you *must* do it this way. A principle says, this *works* and has through all remembered time.

___

JOHN LAROCHE:

Point is, what’s so wonderful is that every one of these flowers has a specific relationship with the insect that pollinates it. There’s a certain orchid looks exactly like a certain insect so the insect is drawn to this flower, its double, its soul mate, and wants nothing more than to make love to it. And after the insect flies off, spots another soul-mate flower and makes love to it, thus pollinating it. And neither the flower nor the insect will ever understand the significance of their lovemaking. I mean, how could they know that because of their little dance the world lives? But it does. By simply doing what they’re designed to do, something large and magnificent happens. In this sense they show us how to live – how the only barometer you have is your heart. How, when you spot your flower, you can’t let anything get in your way.

___

SUSAN ORLEAN:

What I came to understand is that change is not a choice. Not for a species of plant, and not for me.

___

CHARLIE KAUFMAN:

I have to go right home. I know how to finish the script now. It ends with Kaufman driving home after his lunch with Amelia, thinking he knows how to finish the script. Shit, that’s voice-over. McKee would not approve. How else can I show his thoughts? I don’t know. Oh, who cares what McKee says? It feels right. Conclusive. I wonder who’s gonna play me. Someone not too fat. I liked that Gerard Depardieu, but can he not do the accent? Anyway, it’s done. And that’s something. So: “Kaufman drives off from his encounter with Amelia, filled for the first time with hope.” I like this. This is good.

the flower of seven colours

Cvetik Semicvetik (Flower of Seven Colours) is a beautiful Soviet children’s animation from 1948, based on a beloved folk tale about a little girl who receives a magic flower with seven free wishes from an old crone. None of her wishes leads to happiness, until the last wish, which she doesn’t use for herself, but for someone else. By making someone else happy, she is made happy too.

There are many different illustrated versions out there, but perhaps the most trippy one comes from the mind of Russian artist Benjamin Losin. Losin apparently illustrated two different versions of this book.

witch’s cradle (1943), marcel duchamp and maya deren

lost things (2010)

Written & directed by Angela Kohler and Ithyle Griffiths

Music – “Sleepwaking” by A Fine Frenzy

the jungle inside us

infinite body collapse

Screening of new video delay works by Alex Carpenter with dancer Alexis Maxwell

Perhaps ghosts don’t exist “between” normal points of focus, but reside at the core of these points. The essence of things lies within the things, not somewhere else. We don’t need to make the things softer and more delicate, just because we imagine an essence that is itself soft and delicate. If anything, we need to make the things LOUDER, MORE forceful, MORE singular. Maybe then, once our perception tires of the surface layers, becomes exhausted, we will at last see the fragile core that has always eluded us.

“Infinite Body Collapse” is a collection of new works by Alex Carpenter, drawn from recent video delay sessions with dancer Alexis Maxwell, as well as audio delay recordings made this summer in an allegedly haunted house in Alexandria, Virginia.

Through Alex’s video delay system, performed actions (danced, drawn, light-operated) are captured and layered continuously upon playback with previous cyclical generations, providing material for the performer to build on in a largely “unthinking” way. The system engages the performer in a focused, ecstatic process of observing and responding, as normal points of focus are saturated, obliterated, and a space is cleared for the unfolding of activity on a different scale.

This excerpt demonstrates perfectly how the best video delay material is built – with an emphasis on potential within the material, rather than a creator’s plan realized “through” material. This is not “composition”, it is excavation – a digging through to something normally invisible…

Microscope Gallery

4 Charles Place, Brooklyn

Saturday October 6th, 7pm ($6)