Category Archives: art

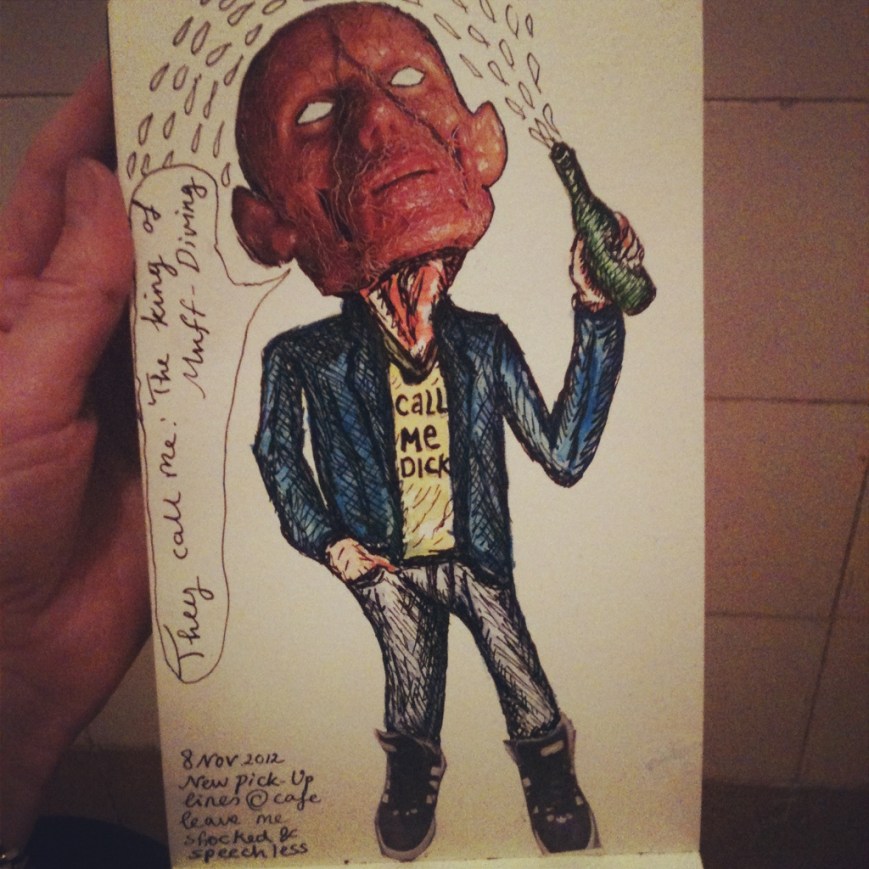

ze noemen me ook wel “de befkoning”.

unknown

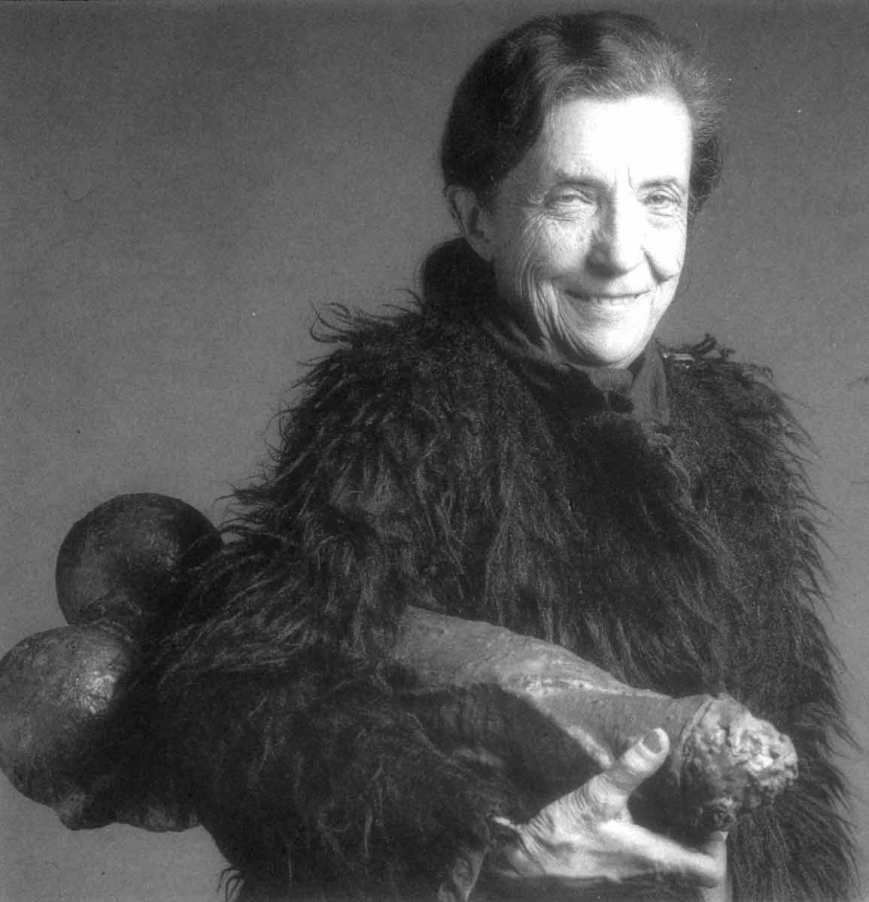

Käthe Kollwitz (July 8, 1867 – April 22, 1945)

“I have never produced anything cold but always to some extent with my blood. I do not want to die…until I have faithfully made the most of my talent and cultivated the seed that was placed in me until the last small twig has grown. I am in the world to change the world.”

http://www.rogallery.com/Kollwitz/Kollwitz-bio.htm

http://www.spaightwoodgalleries.com/Pages/Kollwitz_self_portraits.html

francine van hove

i need to release myself..

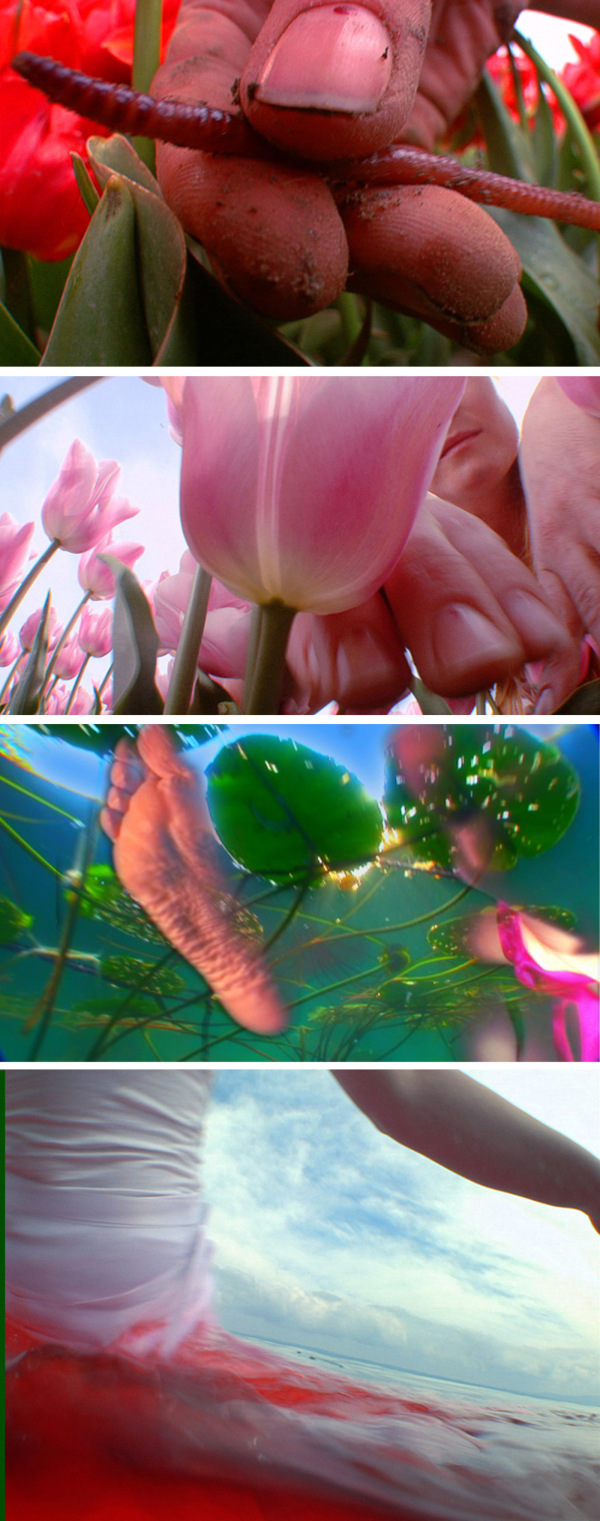

still from pour your body out (7354 cubic meters), by pipilotti rist

bataille (at least)

“If, cruel, it does not invite us to die in ravishment, art at least has the virtue of putting a moment of our happiness on a plane equal to death.” – The cruel practice of art

no one brings flowers to the mental hospital.

bloom

by anna schuleit. 2003.

28 000 potted flowers in a psychiatric institution set for demolition.

fleur

Nobuyoshi Araki´s polaroids with Irina Ionesco

the righteous mind by jonathan haidt

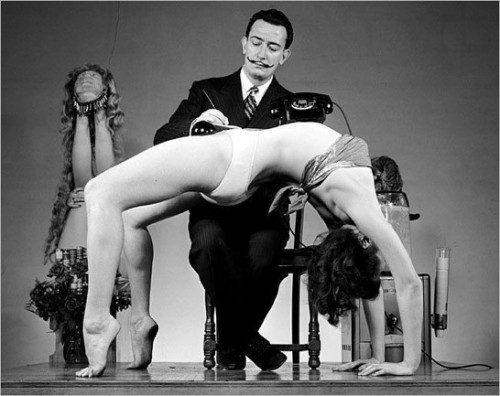

Andres Serrano´s Piss Christ is a photograph is of a small plastic crucifix submerged in what appears to be a yellow liquid. The artist has described the substance as being his own urine in a glass. The photograph was one of a series of photographs that Serrano had made that involved classical statuettes submerged in various fluids—milk, blood, and urine.The full title of the work is “Immersion (Piss Christ)”.The photograph is a 60×40 inch Cibachrome print. It is glossy and its colors are deeply saturated. The presentation is that of a golden, rosy medium including a constellation of tiny bubbles. Without Serrano specifying the substance to be urine and without the title referring to urine by another name, the viewer would not necessarily be able to differentiate between the stated medium of urine and a medium of similar appearance, such as amber or polyurethane.

Serrano has not ascribed overtly political content to Piss Christ and related artworks, on the contrary stressing their ambiguity. He has also said that while this work is not intended to denounce religion, it alludes to a perceived commercializing or cheapening of Christian icons in contemporary culture.

” Here’s a thought experiment. Are you deeply offended by works of art such as Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ, which depicts Jesus as seen through a jar of urine, or Chris Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary, which shows Mary smeared with elephant dung? So offended that you think they ought to be banned and the galleries that display them prosecuted? No? OK, then try replacing the religious figures in these pictures with the sacred icons of progressive politics, people such as Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela. How would you feel if you walked into an art gallery and saw an image of King submerged in urine or Mandela smeared with excrement?

Many people are likely to feel torn. Liberals know the reasoned arguments for freedom of expression and the importance of being consistent on matters of principle. On the other hand, it would be surprising if they did not also feel disgusted and affronted. How dare anyone pass off such gratuitously offensive images as works of art? Shouldn’t they be stopped? Jonathan Haidt, who gives a version of this thought experiment in his provocative new book, wants us to know that reason and instinctive outrage are always going to co-exist in cases like this. What’s more, in most instances, it’s the outrage that will be setting the agenda.

The arresting image Haidt gives for our sense of morality is that it’s like a rational rider on top of an intuitive elephant. The rider can sometimes nudge the elephant one way or the other, but no one should be in any doubt that the elephant is making the important moves. In fact, the main job of the rider is to come up with post-hoc justifications for where the elephant winds up. We rationalise what our gut tells us. This is true no matter how intelligent we are. Haidt shows that people with high IQs are no better than anyone else at understanding the other side in a moral dispute. What they are better at is coming up with what he calls “side-arguments” for their own instinctive position. Intelligent people make good lawyers. They do not make more sensitive moralists.

Where do these moral instincts come from? Haidt is an evolutionary psychologist, so the account he gives is essentially Darwinian. Morality is not something we learn from our parents or at school, and it’s certainly not something we work out for ourselves. We inherit it. It comes to us from our ancestors, ie from the people whose instinctive behaviour gave them a better chance to survive and reproduce. These were the people who belonged to groups in which individuals looked out for each other, rewarded co-operation and punished shirkers and outsiders. That’s why our moral instincts are what Haidt calls “groupish”. We approve of what is good for the group – our group.”

Read the rest of Runciman´s text here

hegel on moral in art

Now as regards art in relation to moral betterment, the same must be said, in

the first place, about the aim of art as instruction. It is readily granted that

art may not take immorality and the intention of promoting it as its principle.

But it is one thing to make immorality the express aim of the presentation, and

another not to take morality as that aim. From every genuine work of art a good

moral may be drawn, yet of course all depends on interpretation and on who

draws the moral. We can hear the most immoral presentations defended on the

ground that one must be acquainted with evil and sins in order to act morally;

conversely, it has been said that the portrayal of Mary Magdalene, the beautiful ~

sinner who afterwards repented, has seduced many into sin, because art makes

repentance look so beautiful, and sinning must come before repentance. But the

doctrine of moral betterment, carried through logically, is not content with

holding that a moral may be pointed from a work of art; on the contrary, it would

want the moral instruction to shine forth clearly as the substantial aim of the

work of art, and indeed would expressly permit the presentation of none but moral

subjects, moral characters, actions, and events. For art can choose its subjects,

and is thus distinct from history or the sciences, which have their material given to

them.

-From Hegel’s Lectures on Aesthetics (The aims of art)

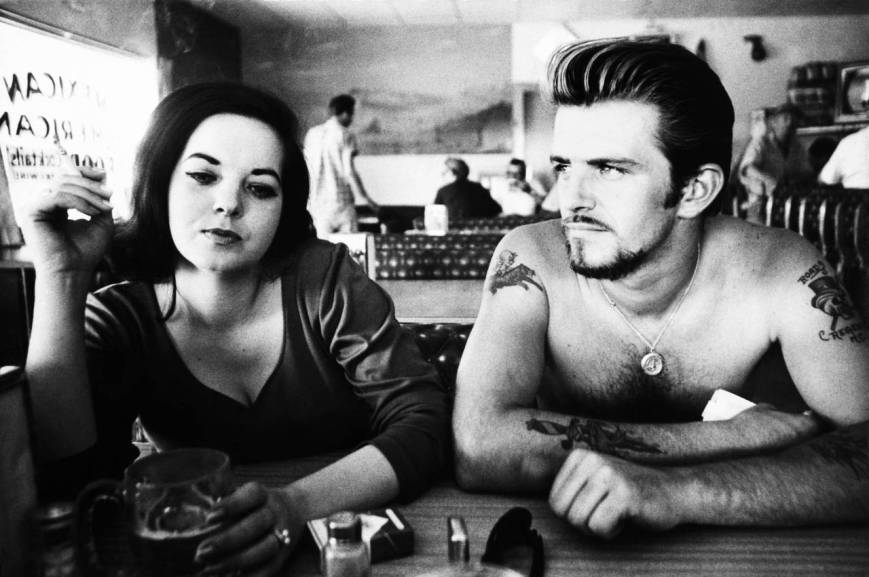

john baldessari, kiss/panic, 1984

magic

Art is magic delivered from the lie of being truth. – Theodor Adorno

guardian of the threshold, 2003,by sigmar polke

‘self portraits of you and me´ by douglas gordon

With ‘Self Portraits of You and Me´ by Douglas Gordon, the viewer is denied engagement with the subject (celebrities) because all discriminating facial features have been removed by burning. Frames backed with mirrors were constructed so that the viewer’s gaze is quite literally reflected back out of the photographs through the holes in the images.

rené magritte – the lovers (1928)

straw feminists!

From the brilliant Hark! A Vagrant by Kate Beaton. Thanks to Pravasan Pillay for sending this!

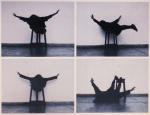

helena almeida

I was recently introduced to the work of Portuguese artist Helena Almeida. It´s difficult to find text that complements it. The simplicity and consistency of her photos, I think, is what makes it so powerful.

hana-bi/maxence cyrin

Images from the film Hana-Bi (Takeshi Kitano, 1997)

Music from Maxence Cyrin – a piano cover of Arcade Fire’s “No Cars Go” (2010).

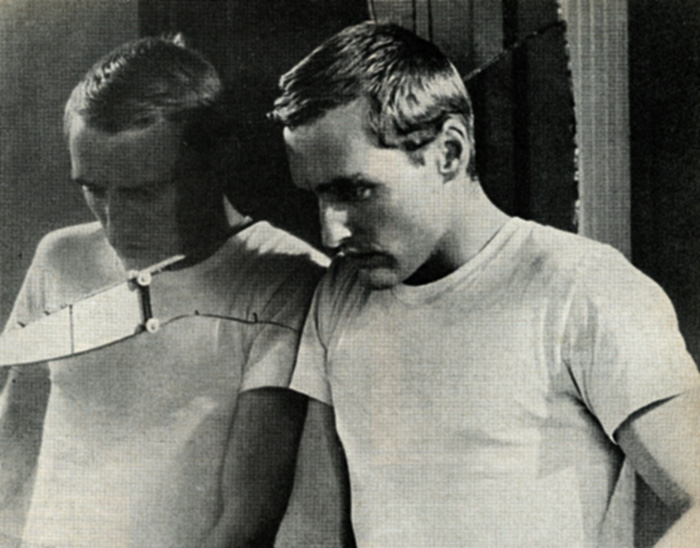

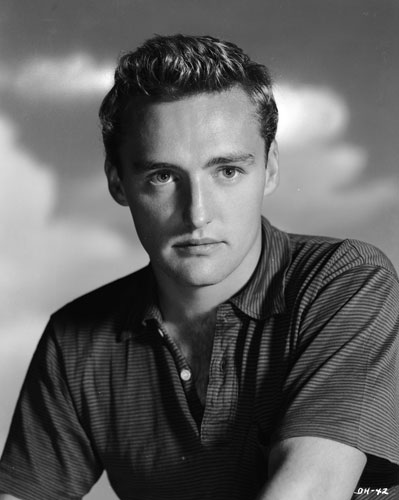

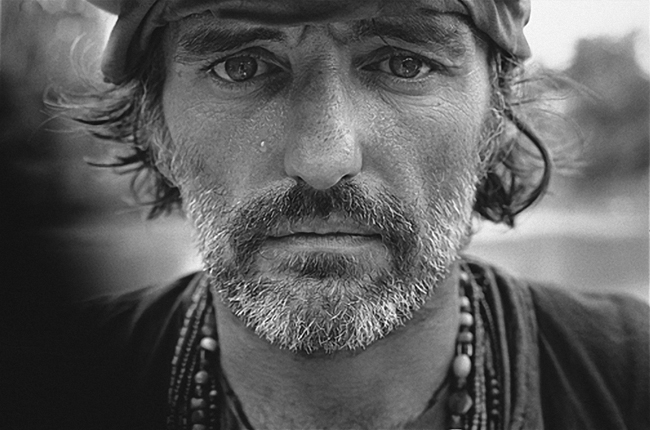

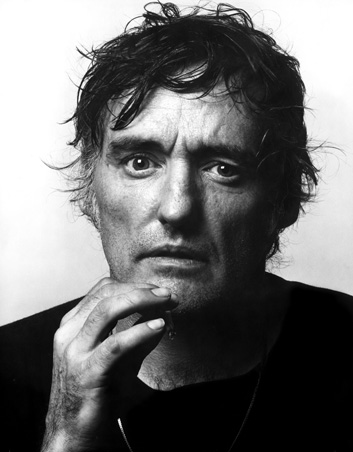

dennis hopper

Here I was, planning a nice, lengthy post about Marjorie Cameron and her art. What an amazing woman/artist/actress/occultist/ collaborator. While searching all kinds of wonderful material I came across Curtis Harrington’s 1961 psychological thriller “Night tide” where Cameron plays the Water Witch alongside Dennis Hopper (great stuff, great jazz.) Thing is, I got totally distracted by images of Dennis Hopper. <3

“eye of the sparrow”

A bad lip reading of the first 2012 US presidential debate. Utterly brilliant.

creative minds “mimic schizophrenia”

By Michelle Roberts – Health reporter, BBC News

Creativity is akin to insanity, say scientists who have been studying how the mind works. Brain scans reveal striking similarities in the thought pathways of highly creative people and those with schizophrenia.

Both groups lack important receptors used to filter and direct thought. It could be this uninhibited processing that allows creative people to “think outside the box”, say experts from Sweden’s Karolinska Institute. In some people, it leads to mental illness. But rather than a clear division, experts suspect a continuum, with some people having psychotic traits but few negative symptoms.

Art and suffering

Some of the world’s leading artists, writers and theorists have also had mental illnesses – the Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh and American mathematician John Nash (portrayed by Russell Crowe in the film A Beautiful Mind) to name just two.

Creativity is known to be associated with an increased risk of depression, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Similarly, people who have mental illness in their family have a higher chance of being creative.

The thalamus channels thoughts

Associate Professor Fredrik Ullen believes his findings could help explain why. He looked at the brain’s dopamine (D2) receptor genes which experts believe govern divergent thought. He found highly creative people who did well on tests of divergent thought had a lower than expected density of D2 receptors in the thalamus – as do people with schizophrenia. The thalamus serves as a relay centre, filtering information before it reaches areas of the cortex, which is responsible, amongst other things, for cognition and reasoning.

strange magic

An art show by Petra Collins of The Ardorous and Tavi Gevinson of Rookie Magazine, held at Space 15 Twenty in Hollywood, CA to celebrate the conclusion of The Rookie Road Trip across the United States.

Music: “Think of You” by Bleached, recorded live during their performance at the closing night party “Rookie Prom Night”.

fillete

the flower of seven colours

Cvetik Semicvetik (Flower of Seven Colours) is a beautiful Soviet children’s animation from 1948, based on a beloved folk tale about a little girl who receives a magic flower with seven free wishes from an old crone. None of her wishes leads to happiness, until the last wish, which she doesn’t use for herself, but for someone else. By making someone else happy, she is made happy too.

There are many different illustrated versions out there, but perhaps the most trippy one comes from the mind of Russian artist Benjamin Losin. Losin apparently illustrated two different versions of this book.