A film by Bill Morrison / Music by Michael Gordon / Blu-Ray Trailer / An Icarus Films Release

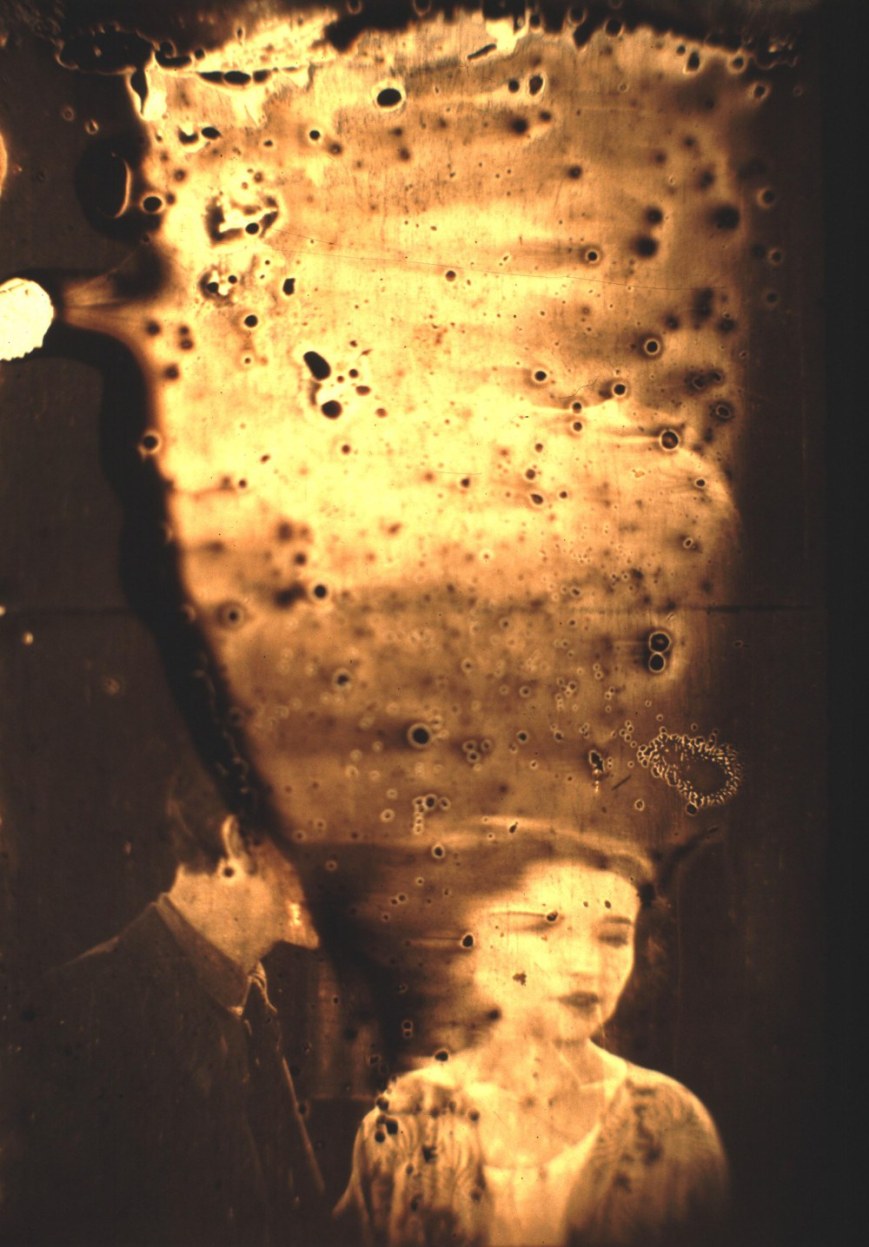

Often compared to Stan Brakhage, Bill Morrison created DECASIA entirely with decaying, old found footage, melded to the music of Bang on a Can’s Michael Gordon, performed by the 55 piece basel sinfonietta. The result is a delirium of deteriorated film stock, a moving avant-garde masterpiece that leaves its meaning open to interpretation and, most importantly, your imagination.

“Bill Morrison’s DECASIA is that rare thing: a movie with avant-garde and universal appeal…. Morrison is not the first artist to take decomposing film stock as his raw material, but he plunges into this dark nitrate of the soul with contagious abandon. Few movies are so much fun to describe. Heralded by a spinning dervish, DECASIA’s first movement seems culled from century-old actualités: Kimono-clad women emerge from a veil of spotty mold, a caravan of camels is silhouetted against the warped desert horizon, a Greek dancer disintegrates into a blotch barrage, the cars for an ancient Luna Park ride repeatedly materialize out of seething chaos.

“DECASIA is founded on the tension between the hard fact of film’s stained, eroded, unstable surface and the fragile nature of that which was once photographically represented. Michael Snow contrived something similar in the chemical conflagration of his 1991 To Lavoisier, Who Died in the Reign of Terror-in which he purposefully distressed new footage. But Morrison is far more expressionistic. A second opposition arises between the lushly deteriorated images and composer Michael Gordon’s no less textured, increasingly ominous drone. (Unlike Philip Glass’s scores, Gordon’s never overpowers the visual accompaniment-even when it escalates to wall of sound.) A third opposition might be termed ideological.

“On one hand, DECASIA…can be taken as a cautionary advertisement for film preservation. [like] Morrison’s 1996 short THE FILM OF HER, an imaginary romance about the preservation of paper prints in the Library of Congress, celebrating what the archivist Paolo Cherchi Usai calls the “monumental necropolis of precious documents.” On the other hand, DECASIA is founded on a deep aesthetic appreciation for decay. (“Cinema is the art of destroying moving images,” per the gnomic Cherchi Uchai.) The solarization, the morphing, the lysergic strobe effects on which the movie thrives, are as natural as the photographic image itself.

“As DECASIA continues, the calligraphy of decay grows increasingly hallucinatory and catastrophic. The sea buckles. Flesh melts. A boxer struggles against the disintegration of the image. Wall Street is half consumed in flames. A dozen little parachutes dot the cracked sky. A group of nuns traverse a courtyard that frames an Italian landscape in severe perspective, evoking a Renaissance vision of the Last Judgment. DECASIA [seems] Hindu in its awesome spectacle of violent flux. The film is a fierce dance of destruction. Its flame-like, roiling black-and-white inspires trembling and gratitude.” —J. Hoberman, The Village Voice

“I popped Morrison’s video into my VCR and within a few further minutes I found myself completely absorbed, transfixed, a pillow of air lodged in my stilled, open mouth. Now, I’m no particular authority on film, but I do know one-Errol Morris. A short time later, when I happened to be visiting him, I popped the video into his VCR and proceeded to observe as Morrison’s film once again began casting its spell. Errol sat drop-jawed: at one point, about halfway through, he stammered, ”This may be the greatest movie ever made.” —Lawrence Weschler, The New York Times Magazine

“Compelling and disturbing! Swimming symphonies of baroque beauty emerge from corrosive nitrate disintegration as rockets of annihilation demolish cathedrals of reality.” —Kenneth Anger, filmmaker

“A stirring, haunting modern masterpiece…Bill Morrison has created a unique artifact, as enigmatically authoritative as Max Ernst’s collage novel “Une Semaine de Bonté.” It makes you think of Joseph Cornell’s memory boxes, Robert Rauschenberg’s time-stuffed assemblages, Anger, Hitchcock. It makes you feel that the art, as opposed to the business, of cinema does have a future – even if it has to be found deep in the past.” —Jonathan Jones, The Guardian