Category Archives: memory

revo

essentially

If only a change of heart could magically repair the concrete effects of centuries of evil and dispossession overnight… It can’t, but thank you, Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, for holding on to hope; for leading by example. If we all started living from an unselfish basis of love and respect, things WOULD shift.

oh sister where art thou? – la vie en rose

From The Lost Phone Recordings. This was recorded on a Nokia 95 phone by my sister Erica and me, playing around in my lounge a couple of years ago, inspired by a music box I picked up in Montmartre in 2007… Our little music project, Oh Sister Where Art Thou?, was about trying to position ourselves playfully in relation to the performance of nostalgic pop classics. While the music may sound simple and cutesy, it was pretty complicated to negotiate. Issues of identity, history, place, privilege, voice, language, racial politics, respect, pastiche, authenticity, memory, erasure, iteration all intertwined… More to be written about this another day when I have time!

slim whitman’s left the earth…

He’s off and joined them ghost riders in the sky at last… Happy hunting, Slim, you legend! Author of the awesomest song ever written with my name in it, hands down:

AND one of the very few foreigners ever to try and sing in Afrikaans!

Read the Guardian’s obituary (thanks, Erica).

marimba memories

In the year 2000 I stopped my beat-up old car to help two guys who were carrying marimbas and gave them a lift up to Melville. On the way we got to chatting, discovered we were all musos, and I decided to come and jam with them while they busked, which I did, a few nights later.

This pair used to come all the way in from Orange Farm township in the Vaal, almost 40km out of Joburg, to busk until midnight outside Melville’s clubs and restaurants, then take a taxi or train home again. So whatever they earned, which was often a pittance, had to cover considerable transport costs – one of apartheid’s architectural legacies, which will take generations to change.

I kept playing with these two guys on the streets, for a couple of years, through winter and summer, on my djembe, cos it was quite something to experience. We were all from Zim, so we had something in common. It wasn’t the first time I had played with so-called black musicians, having played djembe with a maskande outfit called Abafana Bakwa Zulu a couple of years previous to this, but busking was new to me.

Busking is quite a cool way to get really fit on your instrument, and tight as a band. It’s kind of halfway between practicing and performing … sometimes you have an audience, and you have to step it up, and sometimes you don’t, and you can experiment with new songs and licks. If a crowd gathers you can hit on a song for like, 10 or 15 minutes, as long as they are getting into it, which can create some pretty deep calluses if you happen to be a drummer.

In winter, it got so cold that I used to play with a T-shirt, long-sleeve shirt, jersey and leather biker jacket on, plus a hat, even though I was drumming full-tilt. The crap thing about playing a djembe drum outside in the cold is that your hands are moving, creating wind, so even though they are hitting the goatskin hard, on the way up and down they are cooling off, and never really warm up.

Time passed and our little group, which we called Chapungu – meaning ‘whirlwind’ in Shona – apparently it has other, mystical connotations – became fairly good. The dudes found a place to store their instruments, or they would store them at my place, making getting to and from our favourite busking place on the corner of 7th and 4th in Melville much easier. We started getting better tips – we even got a R200 note from a tourist once – and we made a free one-day recording dubbed Sons of the Sun with a guy called Adrian Ziller, bless his heart. My friends helped to design the album cover and print it.

I started visiting the dudes in Orange Farm, which was a full-on jol. Many so-called whites think townships are miserable places, full of suffering and hardship. I’m sure they can be, especially at night in winter, or when the wind howls through Orange Farm, whipping up the dust.

But on my visits, I found a tangible sense of community; neighbours would wander in while we played and get into the vibe. Gangs of kids and dogs would pass by; fences were few and far between. I was uplifted by the music, which was, I guess, our common language, and started playing at events with the dudes, at schools, cultural gatherings, sports meetings, weddings.

There were quite a few kids who used to come and play with the adults; generally the girls would dance and the boys would drum or play on the marimbas, which were all handmade. We started making uniforms for them, with cloth supplied by my friends, or gathered from here and there in the township. The singer’s partner was carving out dance routines for the girls. Things were gathering momentum.

There was a couple in Joburg who were also keen to help our band; they had access to a trust fund, and donated some money which was used to buy tools, which were to be used for making marimbas. We also tried making drums, but it’s not an easy thing to make a good drum.

This couple took us on a trip to visit the Khomani San, who had been granted land by the SA government – but not the means to make a living from it. This couple, they were trying to set things up for some of the Bushmen, a camp which tourists could sleep at, a place to grow indigenous plants, that kind of thing. We met Dawid Kruiper, who was quite famous for his role in getting the land, and a couple of San sangomas. We slept in the camp, which was full of large, black scorpions, and read Tarot cards on the roof of the Landrover, while high on Sceletium, which gives you loads of energy, a natural speed. We dropped our pants and gave brown-eye to the bottle store. It was quite a trip.

Then the couple organised a group of musicians and performers to go on a country-wide tour to advertise a new MTN product. It was called the Multi-Talented Nomad tour, but I didn’t go on it, cos I was working full-time and couldn’t get two weeks’ leave. The guys went on the tour, made a couple of thousand bucks, and decided to go and visit the same Bushmen again, but this return trip didn’t go too well. They apparently shagged some of the Bushmen prostitutes and at least one of them caught AIDS. The singer, a short, fiery character with only one eye – died a few years later. He didn’t make it to the era of ARVs, when having AIDS is no longer a death sentence.

Things had started falling apart even before he died. As soon as we got funding, he and the bassist started arguing about who owned what, and the tools bought with the funding were kept at the singer’s place, and the whole positive vibe started crumbling.

Sometimes they would bitch at me about each other and I just hated being the middle. Fuck that. I really didn’t want to take sides. I was trying to help, not because I thought I should, but because I had just ended up getting involved in the music with these guys and I often had the means to help – the access to transport, to money, to the media. It was unavoidable, but sometimes it had unforeseen consequences.

Eventually, Chapungu broke up, and shortly afterward I was invited to take part in a musical play at the Aardklop festival in Potchefstroom, with the bassist and a group of performers from Orange Farm. We had a teacher who had toured Germany and he knocked our performance into shape, around the idea of a Magic Marimba Tree, from which music came, and provided nourishment to a parched land. I was the white priest, and wore a dog-collar for the role.

When we drove down to Potch I was the only so-called white in the cast of about 14 people. We played on the fringe of the festival and did workshops in the townships. I ate and slept in a room full of blacks, who seldom spoke English … my fault for not knowing Zulu, I guess. The best part was between gigs, as we jammed all day at the backpackers we were staying in, often with outsiders from the festival, who heard us and joined in.

Our mentor came to watch our final performance, hated it, and crapped all over us. We were totally dispirited. Then he wanted to ride back to Joburg in my car, not the overloaded minibus the rest of the crew were to travel in. I split before he could get in, pissed off with his attitude. We had tried our hardest to do a good show. Then we couldn’t get our money out of him. We only got paid after I threatened to put a debt collector on his ass.

The most vivid memory from the whole show, which went on for about a week, was when a beautiful young woman in the cast, who I had been eyeing from the start, stood behind me on the stage and softly put her hands on my shoulders, during the encore. Nothing more happened, but it was an intimate acknowledgment. I see you.

After Aardklop, some of the performers started congregating round the bassist’s place, practicing on the marimbas, and continuing with coaching kids, who would come in after school to play. They were also playing at a nearby school, the kids were winning prizes for their performances, it was all very organic and grassroots. I set up a website for the group. We started playing gigs at cultural events like the Green Africa Party, and then got onto the books of booking agencies, and began playing at corporate events like year-end parties. We made business cards, bought bright uniforms, and started playing quite regularly. This was before the recession, which killed the golden goose of regular corporate gigs, for us and loads of other musicians, including my drum teacher.

I was still doing a day-job, and was asked to write a piece on jazz experimental maestro Zim Ngqawana by the Daily Sun. I met his agent at the Zimology Institute, which he had set up for his jazz students, ironically right next to Orange Farm township. I got to know his agent better, and she helped us to set up an NGO for the musical training of the township kids. After some applications – again, with the help of a friend – we obtained funding, enough to provide the adults with salaries for a couple of years, and to buy some better musical instruments.

This era was our peak. Both the kids and the adults were getting lots of gigs. The kids took part in the FNB Dance Festival a couple of times and won prizes at the National Marimba Competition. They appeared on TV shows and in newspapers; soon we had an entire album of photos and clippings.

The adult group was traveling all over Gauteng and beyond, playing at weddings and parties and openings. A really good (so-called white) guitarist joined the crew, adding an extra car and skilled licks. I evolved a new style of playing the drums, with the djembe where the snare usually stands, and the snare off to the left. I could switch fast between snare and djembe, and play hi-hat and bass foot with both.

We had a huge repertoire of songs, way over 50 songs; some were covers, but many were originals, which had evolved over years of playing. We were playing gospel songs, African jazz, traditional African songs, including some Chimurenga stuff (Zim protest music) and some more bluesy and reggae stuff.

We got a trailer to put the marimbas in; slept over in posh places and demanded, and got, proper meals and treatment from clients, via the contracts with our agencies. Achimota also brought out a CD, recorded free of charge by Brendan Jury, called Ukuxolelana (Forgiveness).

But, after a time, cracks began to show. A key member of the group left to pursue his own musical career. His replacement had less energy and the group, already low on vibrancy, started losing impetus. The recession provided less jobs … the funding for the NGO dried up. The problem of getting to practices, when the guys were 40km out of town, was a thorn in our flesh from the start, but it didn’t matter when we were all into the whole thing – we basically practiced when we played at gigs. Now it was just this massive divide. We weren’t learning new songs, and things were getting stale.

I started standing back, trying to get the other members of the band involved in setting up gigs, obtaining funding, running things themselves. But no-one seemed willing, or able, to keep the ball rolling. I became tired of putting in time and effort, to make things happen: organising gigs, drawing money, sorting paperwork, dealing with clients, auditors and agents.

There were two final straws which made me pull out after twelve years of playing with my marimba mates. On both occasions, we were booked to play for corporate clients, and the guys didn’t pitch on time. I was left carrying the can, got crapped out by the agent and client both times, and, on the last gig, we lost our one remaining agent in the process. That was it.

I had so many experiences with these guys. We travelled thousands of kilometres together, listening to reggae and world music, dreaming of the day when Mugabe would finally die and we could visit Zim to dance on his grave. We often slept in the same room en route to gigs, and I even shared the same bed with them a couple of times.

We played to ecstatic, wildly dancing audiences, and totally bored executives, who would have likely preferred wallflowers to our presence… the catering staff at events was usually our best audience! We fixed broken trailers, cars, instruments, egos and homes together. We busked in Newtown for the whole of the Fifa World Cup. I even did sweat lodges and took psychedelics with some of the dudes.

But there was always that line, that divide, between black and white, between middle-class and poor, between living in town and living in township. It was crossed at times, but it always returned. I count myself lucky that I caught a glimpse of a totally different type of lifestyle and culture to that of white urban Johannesburg.

The door to Orange Farm is still slightly open. I still see the bassist now and then; he is teaching marimbas at a school in Joburg, and is now playing with his uncle, from Zim, who taught him how to play. That sounds innarestin. Me and the guitarist are going to go check it out one of these days. Because there is something utterly organic and magical about playing marimba music. No getting round that.

There were times when I grew frustrated, because things didn’t pan out the way I hoped they would, but overall I don’t regret the experience. Things are born and then they die. I read, in an article on South African NGOs, that you never know what effect you are going to have when you set up structures in poor communities. You have an idea of things going one way; they end up going in another. There might be one or two kids who become brilliant performers after having played with Achimota or Chapungu, or perhaps it changed their lives in some other way, a way which I couldn’t possibly have predicted. That would be enough. For me, my life and music were sure as hell enriched.

Having reread what I just wrote, I realise how much my friends and partners helped me, every step along the way with this crazy adventure, and if they ever read this, thanks a ton guys. We couldn’t have done it without you. At base, at heart, people want to help each other; often, they just don’t know how, but there channels, if you look, or if they find you. This whole dog-eat-dog system that’s been forced down our throats, it’s a load of balls. A lot of us are learning to see past that now. I hope it keeps spreading.

“like me, you must suffer in rhythm”

The truth is that I can’t put down my pen: I think I’m going to have the Nausea and I feel as though I’m delaying it while writing. So I write whatever comes into my mind. Madeleine, who wants to please me, calls to me from the distance, holding up a record:

“Your record, Monsieur Antoine, the one you like, do you want to hear it for the last time?”

“Please.”

I said that out of politeness, but I don’t feel too well disposed to listen to jazz. Still, I’m going to pay attention because, as Madeleine says, I’m hearing it for the last time: it is very old, even too old for the provinces; I will look for it in vain in Paris. Madeleine goes and sets it on the gramophone, it is going to spin; in the grooves, the steel needle is going to start jumping and grinding and when the grooves will have spiralled it into the centre of the disc it will be finished and the hoarse voice singing “Some of these days” will be silent forever.

It begins. To think that there are idiots who get consolation from the fine arts. Like my Aunt Bigeois:

“Chopin’s Preludes were such a help to me when your poor uncle died.” And the concert halls overflow with humiliated, outraged people who close their eyes and try to turn their pale faces into receiving antennas. They imagine that the sounds flow into them, sweet, nourishing, and that their sufferings become music, like Werther; they think that beauty is compassionate to them. Mugs. I’d like them to tell me whether they find this music compassionate. A while ago I was certainly far from swimming in beatitudes. On the surface I was counting my money, mechanically. Underneath stagnated all those unpleasant thoughts which took the form of unformulated questions, mute astonishments and which leave me neither day nor night. Thoughts of Anny, of my wasted life. And then, still further down, Nausea, timid as dawn. But there was no music then, I was morose and calm.

All the things around me were made of the same material as I, a sort of messy suffering. The world was so ugly, outside of me, these dirty glasses on the table were so ugly, and the brown stains on the mirror and Madeleine’s apron and the friendly look of the gross lover of the patronne, the very existence of the world so ugly that I felt comfortable, at home.

Now there is this song on the saxophone. And I am ashamed. A glorious little suffering has just been born, an exemplary suffering. Four notes on the saxophone. They come and go, they seem to say: You must be like us, suffer in rhythm. All right! Naturally, I’d like to suffer that way, in rhythm, without complacence, without self-pity, with an arid purity. But is it my fault if the beer at the bottom of my glass is warm, if there are brown stains on the mirror, if I am not wanted, if the sincerest of my sufferings drags and weighs, with too much flesh and the skin too wide at the same time, like a sea elephant, with bulging eyes, damp and touching and yet so ugly? No, they certainly can’t tell me it’s compassionate—this little jewelled pain which spins around above the record and dazzles me. Not even ironic: it spins gaily, completely self-absorbed; like a scythe it has cut through the drab intimacy of the world and now it spins and all of us, Madeleine, the thick-set man, the patronne, myself, the tables, benches, the stained mirror, the glasses, all of us abandon ourselves to existence, because we were among ourselves, only among ourselves, it has taken us unawares, in the disorder, the day to day drift: I am ashamed for myself and for what exists in front of it.

It does not exist. It is even an annoyance; if I were to get up and rip this record from the table which holds it, if I were to break it in two, I wouldn’t reach it. It is beyond—always beyond something, a voice, a violin note. Through layers and layers of existence, it veils itself, thin and firm, and when you want to seize it, you find only existants, you butt against existants devoid of sense. It is behind them: I don’t even hear it, I hear sounds, vibrations in the air which unveil it. It does not exist because it has nothing superfluous: it is all the rest which in relation to it is superfluous. It is.

And I, too, wanted to be. That is all I wanted; this is the last word. At the bottom of all these attempts which seemed without bonds, I find the same desire again: to drive existence out of me, to rid the passing moments of their fat, to twist them, dry them, purify myself, harden myself, to give back at last the sharp, precise sound of a saxophone note. That could even make an apologue: there was a poor man who got in the wrong world. He existed, like other people, in a world of public parks, bistros, commercial cities and he wanted to persuade himself that he was living somewhere else, behind the canvas of paintings, with the doges of Tintoretto, with Gozzoli’s Florentines, behind the pages of books, with Fabrizio del Dongo and Julien Sorel, behind the phonograph records, with the long dry laments of jazz. And then, after making a complete fool of himself, he understood, he opened his eyes, he saw that it was a misdeal: he was in a bistro, just in front of a glass of warm beer. He stayed overwhelmed on the bench; he thought: I am a fool. And at that very moment, on the other side of existence, in this other world which you can see in the distance, but without ever approaching it, a little melody began to sing and dance: “You must be like me; you must suffer in rhythm.”

The voice sings:

Some of these days

You’ll miss me, honey

Someone must have scratched the record at that spot because it makes an odd noise. And there is something that clutches the heart: the melody is absolutely untouched by this tiny coughing of the needle on the record. It is so far—so far behind. I understand that too: the disc is scratched and is wearing out, perhaps the singer is dead; I’m going to leave, I’m going to take my train. But behind the existence which falls from one present to the other, without a past, without a future, behind these sounds which decompose from day to day, peel off and slip towards death, the melody stays the same, young and firm, like a pitiless witness.

The voice is silent. The disc scrapes a little, then stops. Delivered from a troublesome dream, the cafe ruminates, chews the cud over the pleasure of existing. The patronne’s face is flushed, she slaps the fat white cheeks of her new friend, but without succeeding in colouring them. Cheeks of a corpse. I stagnate, fall half-asleep. In fifteen minutes I will be on the train, but I don’t think about it. I think about a clean-shaven American with thick black eyebrows, suffocating with the heat, on the twenty-first floor of a New York skyscraper. The sky burns above New York, the blue of the sky is inflamed, enormous yellow flames come and lick the roofs; the Brooklyn children are going to put on bathing drawers and play under the water of a fire-hose. The dark room on the twenty-first floor cooks under a high pressure. The American with the black eyebrows sighs, gasps and the sweat rolls down his cheeks. He is sitting, in shirtsleeves, in front of his piano; he has a taste of smoke in his mouth and, vaguely, a ghost of a tune in his head. “Some of these days.” Continue reading

lush – light from a dead star

The first track off the album Split (4AD, 1994).

frida boccara – les moulins de mon coeur

My dad was a fan of Frida Boccara and I grew up hearing this wonderful interpretation of Michel Legrand’s most popular composition, “Les Moulins de Mon Coeur”/”The Windmills of Your Mind”.

not daisy – this is the thing

A cover of a song by Fink.

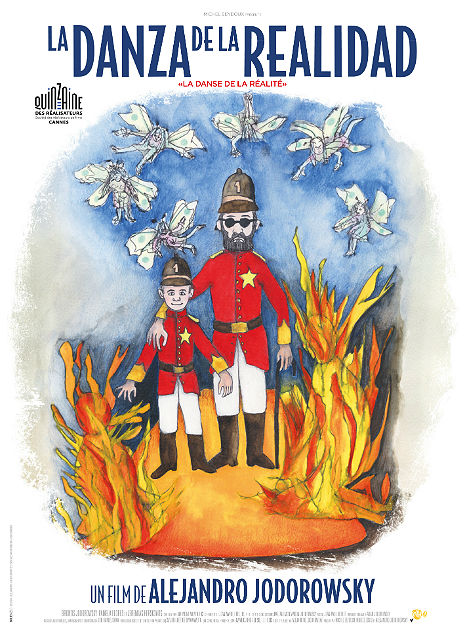

alejandro jodorowsky’s new film

The Guardian review from Cannes 2013 has this to say:

The extinct volcano of underground cinema has burst into life once again — with a bizarre, chaotic and startling film; there are some longueurs and gimmicks, but The Dance of Reality is an unexpectedly touching and personal work. At the age of 84, and over 20 years since his last movie, Alejandro Jodorowsky has returned to his hometown of Tocopilla in the Chilean desert to create a kind of magic-realist memoir of his father, Jaime Jodorowsky, a fierce Communist whose anger at the world — at his son — was redoubled by the anti-Semitism the family faced.

Of course, the entire story is swathed in surreal mythology, dream logic and instant day-glo legend, resembling Fellini, Tod Browning, Emir Kusturica, and many more. You can’t be sure how to extract conventional autobiography from this. Despite the title, there is more “dance” than “reality” — and that is the point. Or part of the point. For the first time, Jodorowsky is coming close to telling us how personal evasiveness has governed his film-making style; his flights of fancy are flights of pain, flights from childhood and flights from reality. And now he is using his transformative style to come to terms with and change the past and to confer on his father some of the heroism that he never attained in real life.

Read more of this review HERE.

goodbye, ray manzarek

The Doors, live in Copenhagen,1968. Ray, I was always even more in love with you than I was with Jim… That organ of yours is what really hypnotised me (that’s what she said).

As my friend Carlo Germeshuys just put it, “Goodbye, Ray Manzarek – without your swirly lounge keyboard old Jimbo wouldn’t have gotten far with his whole bozo Dionysus act.” Oh wait, Carlo says he was referencing a diss by Lester Bangs. Well, whatever. “Bozo Dionysus” = best description of Jim Morrison ever.

HERE‘s an obituary from Rolling Stone.

whispers in the deep

Matt Temple, of the excellent African music blog Electric Jive, has just uploaded another fascinating compilation of rare and historical sounds. This time the focus is on music and censorship in South Africa, and tracks span the period from 1960 to 1994. Accompanying the download link is an essay by Peter M Stewart, written in 2003, when this compilation was originally made, which provides some context for listening.

“Given the recent Secrecy Bill passed by the South African Parliament it’s worth reflecting on music that caught the attention of the censors during the previous dark period of Apartheid… this is a compilation I put together for private distribution in August 2003, almost 10 years ago. It fits the Bill!

“Whispers in the Deep collects a number of anthems, agit-pop songs, and propaganda pieces. Many of the tracks were intended as direct responses to the South African social order as it was prior to 1994. The other tracks might as well have been. Nevermind the revolution, nothing was televised in South Africa prior to 1976.

“Whispers in the Deep also documents some of the ways in which access to popular music was restricted in South Africa – the obstacles that prevented persons resident in South Africa from listening to songs, hearing them broadcast, or seeing them performed. It explores the cultural boycott, censorship by the state in South Africa, and various manifestations of the ‘climate of censorship’.”

Read more and download it HERE.

emmylou harris – coat of many colors

Written by Dolly Parton, from a live broadcast on German TV in 1977.

twin shadow – tether beat

Loving this track at the moment:

Twin Shadow, AKA George Lewis Junior, is doing something interesting while touring: he’s collecting narratives from people online and weaving them into his itinerary. Check out his call for stories:

“Welcome to the Twin Shadow True Story tour, As some of you may know, My father and I have written stories for every stop on the tour, True Stories from our own lives and the people around us. I’m always trying to keep the tours that we do special, I think that, while we live our lives in unison, digitally, and without lines and boundaries on the internet (which I think is amazing), we are still very much from different places. The Line that divides Florida from Georgia is still a hard line. I feel it when I talk to someone from my side of that divide. So I’m asking fans to write stories about where they are from or where they currently call home. Tell us about a place in your town that holds one of your stories. This isn’t a tweet, really tell me in as many words as you want about the time you stole money from the cash register at your old coffee shop, about the time you had your first kiss out the back of the cinema. Tell me everything about those places, and when we come to your town or city we will try to visit these places, and take some photos there. Once I get all the submissions, I’d like to pick the best ones, publish them on my tumblr and read the stories on my soundcloud Podcast called FORGET RADIO.

I love our short form world, but this is a call to talk a bit more about the details that make your lives unique from mine. So often we (bands) roll through your towns with a stop at a grocery store, a gas station, and if you are Twin Shadow your local arcade and go cart racing complex. We wanna know about the rivers you visit, the book stores you love, the bars you drink at, the fields you’ve slept in. This is my wish, let it be known, let it be done.

G

Submit your stories HERE.”

freedom

tell your stories

yrsa daley-ward – up home

Shot on Location in London & Cut by Isaac Ssebandeke of I am Freshcold. 2012. More of Yrsa’s work can be found on Soundcloud and on Tumblr.

Thanks to Clair Cantrell for sharing this with me.

shintaro kago – the memories of others

nick cave on his love for wikipedia

Ag, BLESS!

Watch more of this Australian Broadcasting Corporation insert from February 2013 – Nick talks about creativity, inspiration, his characters and his penchant for observation – HERE.

lauren bacall on companionship

Lauren Bacall interviewed in 1994. Honest and smart… And how!

russell brand on margaret thatcher

‘The blunt, pathetic reality today is that a little old lady has died, who in the winter of her life had to water roses alone under police supervision. If you behave like there’s no such thing as society, in the end there isn’t. Her death must be sad for the handful of people she was nice to and the rich people who got richer under her stewardship. It isn’t sad for anyone else.’

‘Barack Obama, interestingly, said in his statement that she had “broken the glass ceiling for other women”. Only in the sense that all the women beneath her were blinded by falling shards. She is an icon of individualism, not of feminism.’

Russell Brand has an intelligent, evocative way with reflection. I remember the piece he wrote when Amy Winehouse died — the fine-grained, personal memories, the honesty. THIS BIT OF WRITING, on a very different sort of figure in his life, has that same quality.

screen test/bang bang

James Dean and Lois Smith: screen test for East of Eden.

Nancy Sinatra – “Bang Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down)” – piano remix.

capital children’s choir – shake it out

Capital Children’s Choir tribute to Florence And The Machine – “Shake it Out”

Orchestrated, arranged and directed by Rachel Santesso

Drum Coach: Nick Marangoni, Recorded and mixed by Andrew Dudman at Abbey Road Studios (2012)

lana del rey – chelsea hotel no 2

Music video by Lana Del Rey performing Chelsea Hotel No 2. (C) 2013 Lana Del Rey, under exclusive licence to Polydor Ltd. (UK). Under exclusive licence to Interscope Records in the USA.

something fishy

goldfish forget, this is what they do.

silverfish eat books;

they cannot help themselves.

i love silverfish.

t.s. eliot – the cocktail party

It will do you no harm to find yourself ridiculous.

It will do you no harm to find yourself ridiculous.

Resign yourself to be the fool you are.

You will find that you survive humiliation

And that’s an experience of incalculable value.

That is the worst moment, when you feel you have lost

The desires for all that was most desirable,

Before you are contented with what you can desire;

Before you know what is left to be desired;

And you go on wishing that you could desire

What desire has left behind. But you cannot understand.

How could you understand what it is to feel old?

We die to each other daily.

What we know of other people

Is only our memory of the moments

During which we knew them. And they have changed since then.

To pretend that they and we are the same

Is a useful and convenient social convention

Which must sometimes be broken. We must also remember

That at every meeting we are meeting a stranger.

There was a door

And I could not open it. I could not touch the handle.

Why could I not walk out of my prison?

What is hell? Hell is oneself.

Hell is alone, the other figures in it

Merely projections. There is nothing to escape from

And nothing to escape to. One is always alone.

Half the harm that is done in this world

Is due to people who want to feel important.

They don’t mean to do harm — but the harm does not interest them.

Or they do not see it, or they justify it

Because they are absorbed in the endless struggle

To think well of themselves.

There are several symptoms

Which must occur together, and to a marked degree,

To qualify a patient for my sanitorium:

And one of them is an honest mind. That is one of the causes of their suffering.

To men of a certain type

The suspicion that they are incapable of loving

Is as disturbing to their self-esteem

As, in cruder men, the fear of impotence.

I must tell you

That I should really like to think there’s something wrong with me —

Because, if there isn’t, then there’s something wrong

With the world itself — and that’s much more frightening!

That would be terrible.

So, I’d rather believe there’s something wrong with me, that could be put right.

Everyone’s alone — or so it seems to me.

They make noises, and think they are talking to each other;

They make faces, and think they understand each other.

And I’m sure they don’t. Is that a delusion?

Can we only love

Something created in our own imaginations?

Are we all in fact unloving and unloveable?

Then one is alone, and if one is alone

Then lover and beloved are equally unreal

And the dreamer is no more real than his dreams.

I shall be left with the inconsolable memory

Of the treasure I went into the forest to find

And never found, and which was not there

And is perhaps not anywhere? But if not anywhere

Why do I feel guilty at not having found it?

Disillusion can become itself an illusion

If we rest in it.

Two people who know they do not understand each other,

Breeding children whom they do not understand

And who will never understand them.

There is another way, if you have the courage.

The first I could describe in familiar terms

Because you have seen it, as we all have seen it,

Illustrated, more or less, in lives of those about us.

The second is unknown, and so requires faith —

The kind of faith that issues from despair.

The destination cannot be described;

You will know very little until you get there;

You will journey blind. But the way leads towards possession

Of what you have sought for in the wrong place.

We must always take risks. That is our destiny.

If we all were judged according to the consequences

Of all our words and deeds, beyond the intention

And beyond our limited understanding

Of ourselves and others, we should all be condemned.

Only by acceptance of the past will you alter its meaning.

All cases are unique, and very similar to others.

Every moment is a fresh beginning.

__

Excerpted from T.S. Eliot’s 1949 play, The Cocktail Party

from “before sunset” – taxi scene

“There’s gotta be something more to love than commitment”…

… “Why are you telling me all this?”

from “before sunset” on connection

julian redpath – shipwrecks

Keep an ear out for this talented songwriter based in Johannesburg. I saw him tonight at Carnival Court in Long Street, Cape Town and was deeply moved by some of his writing… The tune I loved most is not on Soundcloud, but this one is pretty fine too.