Note on the author: Olivier Chow is a former senior protection officer of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and has led investigations on war crimes in Afghanistan, Cambodia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Macedonia. He is currently finishing a PhD in critical theory at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), London University, working on the theory and visual mediation of cruelty. His main interests concern French theory and in particular the work of Georges Bataille, fetishism, violence, popular culture and tribal arts. He has also worked for UNESCO, Sotheby’s and a private collection of surrealist art. The following article was first published HERE.

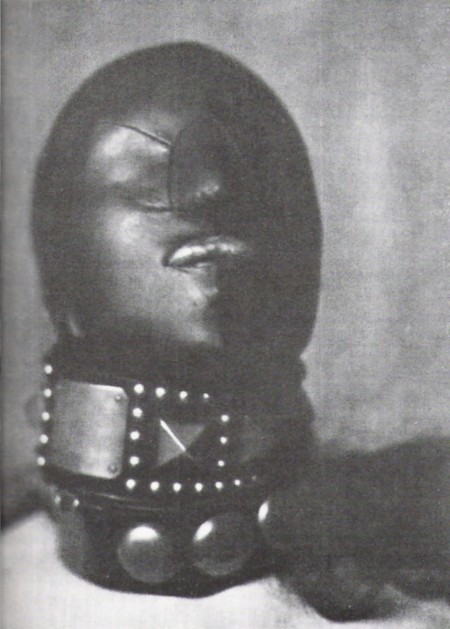

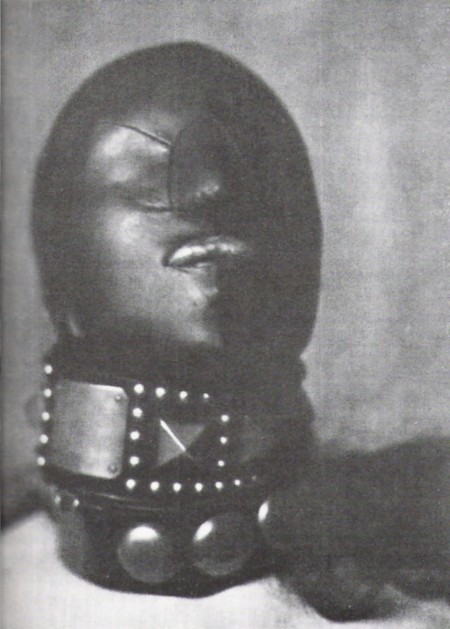

Jacques-André Boiffard, Untitled, Article “Le Caput Mortuum ou la Femme de l’Alchimiste”, Documents, 1930, No 8

In this paper we shall explore desire from the perspective of transgression and, to be precise, desire generated by the transgressive space born from the oscillation between attraction and repulsion, or what the French surrealist Georges Bataille named ‘inter-repulsion’. We shall argue that the ultimate object of inter-repulsion is death itself and, as such, inter-repulsion brings forth not only the subject and its discontents but also the social with its taboos and prohibitions. Inter-repulsion will be discussed in relation to the visual culture of Documents, a dissident and short-lived surrealist journal (1929-1930) that has recently come back to life at the Hayward in the exhibition “Undercover Surrealism.” [1] One of the pièces maîtresses in the main hall of the exhibition is a photograph by Jean-Jacques Boiffard, the most prominent photographer of the journal: a photograph of a magnified big toe around which our discussion will centre. This photograph has become an emblem for a surrealism that has done away with the ‘marvellous’ – which it literally shat on – and that has shamelessly promoted the ‘low’ (bassesse ) and the ordure: the surrealism of Georges Bataille which opposed the impossible of the real to Breton’s possible of the imagination. The big toes had a task – for Bataille, words and images always had to do something: to bring forth through the sensations of visceral reactions and gut feelings what had remained hidden and repressed. The object of repression staged in Documents was a desire rooted in death. Thus we shall argue that inter-repulsion creates a pornography of death since it shows us our darkest and most obscene object of desire. Our discussion will be divided into two sections: first we shall explore the big toe as ‘idol’, second as ‘ordure’.

Documents was initially intended as a scientific review, albeit one with a unique and innovative twist. It brought together high and popular art (beaux arts and variétés), archaeology and ethnographic art. Documents’ ambiguous mission statement already contained the seeds of its undoing: “the most provoking as yet unclassified works of art and certain unusual productions, neglected until now, will be the object of studies as rigorous and scientific as those of archaeologists.” As early as issue four, the provocative, disturbing and frankly monstrous became the focus of the journal and it quickly became a war machine against surrealism: “Documents made clear what surrealism was not; what, under the aegis of Breton, it could not be.” [2] It would be “the abscess burst each month from surrealism.” [3]Documents elaborated a common theoretical front against positivism and idealism reducing all images and objects (dead animals, big toes, abattoirs, ancient coins, high and ‘primitive art’) to document status. It promoted a fragmenting, magnifying and anti-aesthetic gaze on the world, privileging the monstrous and corporeal. Facts from ethnography, faits divers andvariétés , religion and culture, were artificially ‘planted’ in order to anchor images and discourse in a reality that was both familiar and yet complete fantasy and fabrication. This mock reality was largely one of distortion and pastiche; a distortion that was also applied to constituted forms (mainly the human body and its architecture). Here the positivism of factual documentation, like the body itself, was perversely subverted: reality was deformed and this was placed in the service of sensations such as vertigo and disgust. The ‘facts’ that were revealed were closer to what Francis Bacon understood as facts: a brutal revelation of a hidden truth about the human condition. These were inseparable from the brutal sensations they imposed on the viewer. These visceral facts, or ‘visual instincts’, fashioned a new and powerful reality where differences between a subject and object were brutally collapsed. This is the sensational reality that the big toes managed to bring about, or in the words of Bataille: “a return to reality…means that one is seduced in a base manner, without transpositions and to the point of screaming, opening his eyes wide: opening them wide, then, before a big toe.”[4] Inter-repulsion inaugurates a brutal return to sensation – not pleasant sensations, rather as we shall demonstrate, sensations of death.

Jacques-André Boiffard’s ‘Big Toes’ were published in Documents number 6, 1929, with a text by Bataille titled ‘Le Gros Orteil’. The two male big toes that appeared here are actually part of a series. Altogether there are three (two male and one female), a sort of “friendly trinity”. [5]The chiaroscuro isolates the toe from the body, providing it with a fetishistic and almost godly aura. Whereas most of the other photographs published in the journal were usually juxtaposed together in a sort of montage that reminded the viewer of the random and haphazard juxtapositions of a newspaper, the big toes stand alone in the magazine, occupying a full page. The visual brutality of the big toes and the mocking tone of the text that accompany the image, are typical of Documents: the provocative and almost ethnographic enterprise on the big toes was not dissimilar to the exploration of eccentric artistic productions, exotic cultures, sacrificial rituals and dismissed historical periods that defined Documents’ anthropological realm.

In his “Gros Orteil”, Bataille describes how feet, for some individuals, are sexually charged. Here Bataille cites the example of the Count of Villamediana who burnt a house in order to carry the queen and stroke her feet or foreign cultures like China where the feet of women are both deformed and venerated. As a fetish, feet and toes are abstracted from the body and turned into independent wholes charged with desire: idols. We shall name these idolised fragments of the body, ‘part-objects’ – a term that designs parts of the body, real or fantasised (penis, breast, food, faeces, toes, et cetera) invested with desire. The destiny of part-objects or ‘érotique combinatoire‘ [6] to use Roland Barthes’ expression, was one of Bataille’s favourite anthropological and symbolic explorations. Part-objects are celebrated in Bataille’s pornographic novels from Histoire de l’Oeil to Madame Edwarda . In Bataille’s Histoire de l’Oeil, the eye is set within a symbolic matrix and a system of correspondences. Histoire de l’Oeil, as Roland Barthes noted, is really the history of an object, its migration and metamorphosis into its symbolic equivalents. Every metamorphosis is like a new station within the migration of the object/organ. The part-object is recited throughout the novel (eye, sun, egg, and their respective seminal liquids), revealing the humid substance of a round phallicism. In Madame Edwarda, Madame Edwarda asks the narrator if he wants to sees her ‘vilaines guenilles’. She exposes her ‘old rags’, a source of anxious fascination. From within these revolting guenilles emanates a dirty gaze that stares at the narrator like a Medusean ‘pieuvre répugnante’ . When the narrator asks her why she does this, she tells him: “Tu vois…je suis DIEU”. [7] In Madame Edwarda, God is a genital revelation. Madame Edwarda’s ‘gazing beast’ is god-like: totemic and sovereign. The big toe photographed by Boiffard is also staged like a genital, repugnant and sovereign creature.

Binet’s seminal essay on fetishism, Le Fétichisme dans l’Amour (1887) was well known to Bataille. It dedicated a few pages to the account of various forms of fetishism related to inanimate objects or fractions of the body, real or symbolic such as hand, feet, hair, eye, voice and smell. Binet combines his theory of fetishism as a sexual perversion with the aesthetics of fetishism. According to Binet, fetishism tends to detach and isolate the part-object from the person to which it belongs. The fetishist tends to transform this part-object into an independent whole. The part-object is thus an abstraction according to Binet. This tendency towards abstraction is also supplemented by a tendency towards generalisation: the cult of the fetishist is not oriented towards a part-object belonging to one specific person. On the contrary, the part-object stands for a sort of genre or ‘monotheism’ to use Binet’s expression that is not attached to one individual specifically but to one abstracted fragment. Finally, Binet observes that there is a tendency towards exaggeration: the volume or the importance of the part-object is enhanced.

Jacques-André Boiffard, Big Toe, feminine subject, twenty-four years old , Documents, No6, 1929

Jacques-André Boiffard, Big Toe, feminine subject, twenty-four years old , Documents, No6, 1929

Jacques-André Boiffard, Big Toe, masculine subject, thirty years old , Documents, No6, 1929

Jacques-André Boiffard, Big Toe, masculine subject, thirty years old , Documents, No6, 1929

Jacques-André Boiffard, Big Toe, masculine subject, thirty years old , Documents, No6, 1929

Jacques-André Boiffard, Big Toe, masculine subject, thirty years old , Documents, No6, 1929

The fetishistic photographic process confers the big toe with a new status as part-object ready to be mapped out by desire and sexualised. The big toe’s sexual persona is here evidently exposed as obscene. Boiffard has mimicked the fetishist gaze observed by Binet. The toes are isolated from their bodies, fragmented, enlarged, staged and dramatised. The magnified, blown-up toes seem impossibly real: ugly, hairy, genital-like. We are literally put face to face with their excessive and nauseous reality. The photographs are cropped, the angle imposes a violent deformation on the toe – they are upside down, brought down if such an operation were possible. It is a portrait that transgresses and subverts the very idea of what a portrait should be: the highest and most noble part of the body has been thrown away and transformed into a grotesque, absurd and scandalous ‘other face’.

The framing of the toe is an act of violence set against the human figure. Bataille’s text refers to material and visual operations of abuse and violence such as “deformation”, “infection”, “tortures”, “pain”, “brutal”. Those forces that deform the human figure are violent forces that Bataille equates with forces of entropy and decomposition, such as those that attack the corpse. The deformation or “alteration” of the human figure was an essential strategy in Bataillean aesthetics: “the word alteration provides the double advantage of expressing a partial decomposition similar to that of corpses and at the same time the expression of the passage to a perfectly heterogeneous state that the protestant professor Otto named the ‘wholly other’, that is the sacred.” [8]

In his classic study of the Holy, the German theologian, philosopher and historian of religions Rudolf Otto (1869-1937), situates the sacred in relation to an a priori emotional structure, the numinosum . In the experience of the numinous, the subject experiences a feeling of intimate dependence towards a higher and independent force. The experience of the “wholly other” [9]: is what Otto describes as “creature-consciousness”. This “creature-feeling” is “the emotion of a creature, abased and overwhelmed by its own nothingness in contrast to that which is supreme above all creatures.” [10] This experience is fundamentally ambivalent, a mélange of attraction and repulsion: this mysterium tremendum is an uncanny experience of awfulness, an awfulness that lies beyond the realm of knowledge, producing a feeling of peculiar dread, a “terror fraught with inward shuddering.” [11] The big toes reek of these creepy “creature feelings”.

Boiffard has also captured the fetish’s destiny as fixation. William Pietz, one of the leading commentators on fetishism, defines the fetish in the following terms: “The fetish is always a meaningful fixation of a singular event; it is above all a ‘historical’ object, the enduring material form and force of an unrepeatable event.” [12] This unrepeatable and traumatic event could be rooted in early childhood beliefs and complexes. Freud and psychoanalysis argue fetishism is linked to the experience of shock that comes about once the absence of a maternal penis is revealed. The fetish becomes a substitute for the penis and a disavowal of that lack. The captions for this big toe could be: “it is not really gone as long as I’m here”. The body as site of revelation of the phallus was a common surrealist visual strategy. One of its most famous expressions is Man Ray’s anatomies (1930). The idea behind that specific visual operation was to de-territorialise bodies, rendering them polymorphously perverse and ‘genital’ by liberating desire from the conventional and limiting mappings of the erogenous zones.

Jacques-André Boiffard, Untitled , Article “Le Caput Mortuum ou la Femme

Jacques-André Boiffard, Untitled , Article “Le Caput Mortuum ou la Femme

de l’Alchimiste », Documents, 1930, No8

We are now going to discuss another famous image of Documents by Boiffard where the body turns into phallus: his untitled image that features a mask by W.B. Seabrook. Michel Leiris in his “Le Caput Mortuum ou la Femme de la l’Alchimiste” published in Documents in 1931, discusses the photograph portraying a woman wearing a mask. The image brings forth both fetishistic memories of desire (sado-masochistic fantasies) and mystic possibilities of religious revelation (could that mask be the face of God, Leiris wonders). For Leiris, a mask can thus open up to desire and the sacred: the mask opens towards what is both foreign and intimate within us. What the mask manages in true fetishistic form is to abstract and concentrate body parts – making them more as well as less real, that is, schematic. Boiffard’s woman becomes more mysterious but also more threatening as her features are disguised by her second leather skin. The woman becomes an abstraction, a generality, a thing or essence (“ chose-en-soi ”). Her severity is tinged with suffering, appealing to our sadism as Leiris argues: “in addition to suffering under the leather skin, being subjected and mortified (which satisfies our will to power and our fundamental cruelty), her head – sign of her intelligence and individuality – is insulted and negated.” [13]Her mouth is reduced to a wound and her body transgressed: the body is naked and the face is masked, an obscene and forced inversion that associates violence to desire. The figure of the woman is profoundly ambiguous and can be seen as either a perpetrator (“ bourreau ”) or a beheaded queen (“reine décapitée ”).

We have now witnessed the uncanny connection between desire and death. This connection is also active in the photographs of big toes. Boiffard restitution of the lost phallus has only been possible through the castrating use of picture cropping that has separated the toe from the foot. The sight of these big toes is not very comforting: on the contrary they signify pain, mutilation and danger. The big toe is a monument to castration: the nail suggests endless cuttings, a ‘thousand cuts’. Continue reading →

Shintaro Kago 駕籠 真太郎) born 1969 in Tokyo, is a Japanese guro manga artist. He made his debut in in the magazine COMIC BOX, in 1988.

Shintaro Kago 駕籠 真太郎) born 1969 in Tokyo, is a Japanese guro manga artist. He made his debut in in the magazine COMIC BOX, in 1988.

Jacques-André Boiffard, Big Toe, feminine subject, twenty-four years old , Documents, No6, 1929

Jacques-André Boiffard, Big Toe, feminine subject, twenty-four years old , Documents, No6, 1929 Jacques-André Boiffard, Big Toe, masculine subject, thirty years old , Documents, No6, 1929

Jacques-André Boiffard, Big Toe, masculine subject, thirty years old , Documents, No6, 1929 Jacques-André Boiffard, Big Toe, masculine subject, thirty years old , Documents, No6, 1929

Jacques-André Boiffard, Big Toe, masculine subject, thirty years old , Documents, No6, 1929 Jacques-André Boiffard, Untitled , Article “Le Caput Mortuum ou la Femme

Jacques-André Boiffard, Untitled , Article “Le Caput Mortuum ou la Femme