An excerpt from Joshua Billings’ paper entitled Hyperion’s symposium: an erotics of reception.

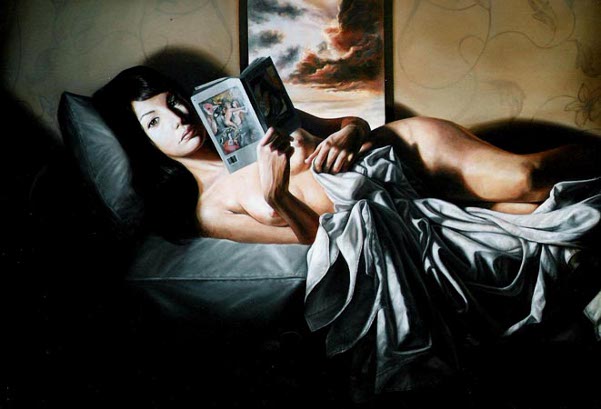

El Crepúsculo de Diotima

Ricardo Celma (1975, Argentina)

Diotima of Mantinea is a present absence in Plato’s Symposium. Her words form the most important of the symposium’s encomia to Eros, but she does not speak them herself. Socrates, her former pupil, relates her lesson in erotics to the assembly. She remains a mysterious figure: her name — ‘honoured by god’ — and her city, cognate with mantis, place her somewhere between human and divinity. Though the main narrative of the Symposium is doubly framed — it records the words of Apollodorus who recounts what he heard from Aristodemus — Diotima is still further removed from the literary present. She exists (if she exists at all) as a liminal, ambiguous being. But this is appropriate to her subject: Eros, a god characterized by perpetual incompleteness.

The Diotima of Friedrich Hölderlin’s Hyperion or the Hermit in Greece (Hyperion oder der Eremit in Griechenland), too, seems poised between being and non-being. As the title character’s beloved, her existence forms the hinge of the entire narrative, yet the pages in which she appears are relatively few and in them, she is most often passive and silent. Most formative for Hyperion, indeed, is her seemingly unmotivated death, reported at second-hand. The form of the novel, a series of retrospective letters from Hyperion, serves to heighten her absence just as the Symposium’s framing places its narrative in a doubly-remembered past. Hölderlin’s Diotima, like Plato’s, exists in eternal mediation, suggesting that Hyperion’s desire cannot be fulfilled, his ideal never realized.

This is the lesson of Diotima in the Symposium. In contrast to the previous speakers, Socrates emphasizes not the positive qualities of Eros, but the poverty that drives the god to seek beauties he does not possess. Socrates reports the speech of Diotima, who disabused him of the notion advocated by his friends. The Eros described by Diotima is liminal, neither beautiful nor ugly, and neither man nor god. He is a daimôn, whose existence is defined by his place between opposing realms. His power is

… interpreting and carrying to gods things from humans, and to humans things from gods: from humans, the entreaties and sacrifices; from gods, orders and exchanges for sacrifices. He is in the middle of both and fills the space between, so that all is bound by him.

Eros is always relational, a mediation between two elements. This is a consequence of his birth, as the child of Penia and Poros, need and resource. Like his mother, he is unattractive and perpetually impoverished, yet he has the skills of his father that allow him occasionally to attain his desire. This makes him a paradox, poor but able to become rich, immortal but able to die: ‘sometimes he flourishes for a day and lives, whenever he has resources, and sometimes he dies, but is brought back to life again through the nature of his father.’ Eros is not a happy medium of his two parents, but an unstable oscillation between states of euporia and aporia.

Eros’ dialectical nature makes him philosophical, and distinguishes him from his parents. Those who are wise (like Poros) feel no need to philosophize, while those who are ignorant (like Penia) cannot comprehend their need. Eros’s philosophical nature is based on reflection; it results from the recognition of his own ignorance. Philosophy is a state of intellectual poverty that uses resource to gain insight:

Being a philosopher he is between a wise man and an ignorant. The cause of this is his birth: for he is from a wise and resourceful [euporos] father, and an unwise and unresourceful [aporos] mother.

Socratic philosophy and erotic desire are parallel; both begin in a state of reflective aporia and strive towards euporia. Socrates’s self-conscious ignorance makes him the exemplary erotic seeker. In this respect, it is particularly important that the figure of Diotima is absent in the dialogue: erotic and philosophical fulfilments are deferred, set off in a mysterious past. Furthermore, Socrates (like the speakers who frame the story) is simply repeating an earlier conversation rather than engaging in his usual dialectics. What remains for the symposiasts as for the reader of the Symposium is a mediated presence that relates knowledge without being able to answer for it.

El Crepúsculo de Diotima

Ricardo Celma (1975, Argentina)

The connection of philosophy and desire suggests a productive nature of Eros, a way it escapes the constant oscillation between want and fleeting fulfilment. As we have already learned, Eros is unable to possess what it desires permanently. Instead of possession of the beautiful, Eros seeks to reproduce with the beautiful:

– Eros, Socrates, she said, is not of the beautiful, as you think.

– But what then?

– Of begetting and bringing forth on the beautiful.

– Let it be so, I said.

– It is so absolutely, she said. And why is it of begetting? Because begetting is eternal and undying as far as it is possible for a mortal. From what we have agreed, it is necessary that with good one desire immortality, if indeed eros is of the good being one’s own always. It is necessary from this very account that eros be also of immortality.

The account of Eros’ activity here changes abruptly: Eros finds a way out of lack, to a creative activity. This also necessitates a redefinition of Eros as desire, not for the beautiful or the good, but for an eternal existence. In place of possession, Eros turns to production. This is the crux on which Hölderlin’s reading of the Symposium will focus, as nostalgia for a lost ideal is transformed into the realization of future possibility. This dynamic constitutes what might be termed an ‘erotics of reception’.

Desire, according to Socrates, necessarily turns from the transient present towards an infinite future. In reporting Diotima’s words, Socrates enacts this temporal reorientation, making her absence the basis for philosophical production. He leads his companions, as erotic desire leads the philosopher, on the ascent to higher forms of beauty, and ultimately, to the idea. This is an increasingly contemplative act, in which desire for a beautiful body yields to desire for a beautiful soul, and ultimately, to knowledge of the essence of beauty:

Beginning from these very beauties, for the sake of that highest beauty he ascends eternally, just as if employing the rungs of a ladder, from one to two, and from two to all beautiful bodies; from beautiful bodies he proceeds to beautiful pursuits, from pursuits to beautiful sciences, and from these sciences arrives at that science which is concerned with the beautiful itself and nothing else, so that finally he comes to know what the beautiful is.

The end of Eros is philosophical fulfilment, conceived as a reflection on immortal beauty. The ascent to the eternal form is parallel to the immortality of giving birth: both begin with a pregnancy of the soul that seeks a beautiful object. From the aporia of mortal bodies, philosophy fashions the euporia of wisdom. The figure of Diotima, an absence that produces knowledge, represents this progress to fulfilment through loss. In the Symposium, as in Hyperion, Diotima’s very pastness makes her the object of an erotic dialectic.