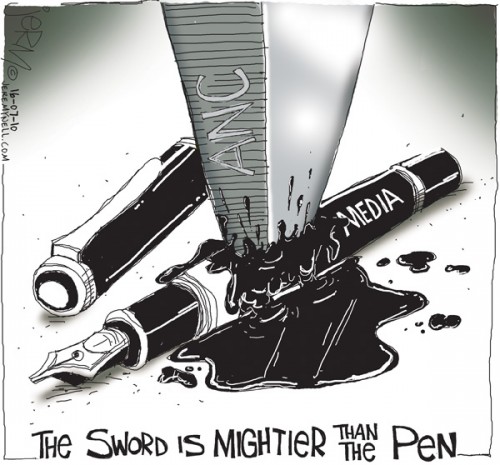

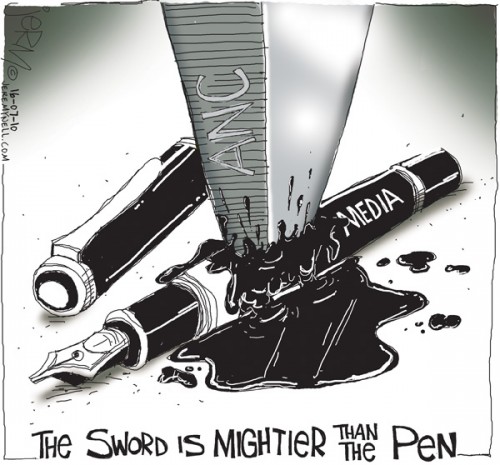

The famous quote ‘the pen is mightier than the sword’ has a different meaning today than it had when the English novelist Edward George Bulwer-Lytton (1803-1873) wrote in 1839: ‘Beneath the rule of men entirely great the pen is mightier than the sword’. Apart from the obvious fact that a sentence fragment cannot convey the same meaning as a full sentence, there are a number of reasons why we can assume there to have been significant changes in the meaning of these frequently quoted words in the last 160-odd years. After an initial non-exhaustive exploration of some of these reasons in order to discuss the contemporary reception of old texts in general, I will present an example of a possible contemporary rereading of the sentence in order to critically approach its form as well as its content in more detail.

From the 19th through to the 21st century, radical shifts have taken place in the social, political and economic systems of the currently ‘European’ nations like England. Class differences have steadily decreased in importance while the levels of literacy have increased enormously. Nowadays readers of literary, journalistic and other texts come from all walks of life and all classes in society, which was not yet the case in Lytton’s time. Due to the cultural complexity of a postmodern and post-industrialised context, readings of this sentence today are not merely permitted to be different, but are necessarily far more numerous and varied than they would have been expected to be in the 1800s.

In the midst of this new plurality of discourses – which is for reasons of brevity and clarity merely stated here and will not be elaborated on – phrases of such universalising nature are rarely coined by writers and other intellectuals today, whereas in its original context a sentence such as this one may have had only one unmistakeable message to almost anyone reading or hearing it, simply because this context was rather narrow. Those who could read and write of course did not all think alike, but they would all more or less have agreed on what kind of meaning was being transmitted with these words. Nowadays we can observe a very different dynamic unfolding: whatever is said publicly immediately enters a broad field of more or less interconnected discourses, which form more or less homogenous or contradictory opinions as to its meaning within – and its relevance to – their own and possibly other world views.

What any given politician is saying on any given day on any given subject is never entirely opaque to anyone reading about it in the paper who has also read the previous day’s edition, but what effectively stands behind these words is ever more difficult to contextualise constructively in terms of its respective outcomes. ‘Right’ and ‘wrong’ are constructs that have become almost interchangeable or irrelevant, because there are so many equally valid viewpoints on any given subject or utterance, which all have a more or less publicly audible – and thereby already minimally validated – voice.

In order to bring meaning to the signifying remnant ‘the pen is mightier than the sword’ of the 19th century message x (as in ‘unknown’) in this widened, or rather exploded context, it is necessary to – at least initially – ‘misunderstand’ it. ‘Misunderstanding’ here shall refer to the application of an interpretation based on the more or less unspecific world knowledge of an individual living in the 21st century, as opposed to assuming to be in the know about what meaning the text had in 19th century England. At best, in any critical approach the inevitability of this process of ‘misunderstanding’ is acknowledged and problematised; else it is taken for granted, or at worst denied. In the last case lies the danger of laying claims to an absolute truth of sorts. Nowadays certain versions alone – of the infinite number of possible readings – may succeed in presenting certain convincing insights, which do not lay claim to finality or completeness.

The penis: mightier than the sword. This modified version arrived at by simply dropping the space between ‘pen’ and ‘is’ and inserting a colon, crassly illustrates the imagery of pen and sword as charged with concepts of maleness. It is psychoanalytically easily accessible: we are presented with two phalluses holding recourse over their size. The reader is asked to identify with the smaller and therefore supposedly weaker member, and he is told that size not only doesn’t matter, but that he will – on this side of the argument – prevail in the face of overpowering adversity, or better still: competition. The question arises: over what? We do not know. Are we to assume that the sword stands for war and the pen for enlightenment – and in effect peace? If this is the case, what we are led to believe in this statement is that war is bad, and that consequently it is to be regarded as disconnected and even structurally different from everything that has to do with writing and reasoning: as ‘mightier’ human endeavours.

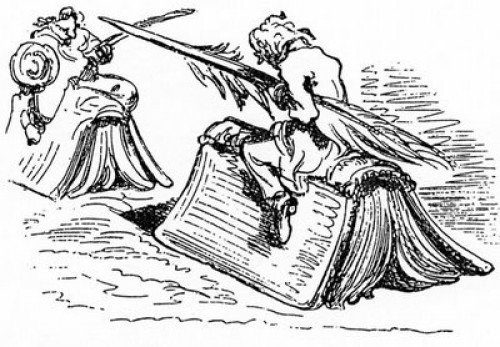

The ‘pen’ here stands for the word, an ideal idea, the thought worth concretising and writing down. The ‘sword’ stands for war, death, planned killing in the name of a higher power or principle. On this literally symbolic level the pen may be mightier than the sword; but moving on from this level it may be argued that the pen harnesses the power that also moves the sword, if less wisely so, and thereby causes greater destruction than the sword alone ever will. Nowadays, if only through the abundance of costume dramas and kung-fu movies, the sword as an image does no longer successfully symbolize chaos and destruction, for in its singularity and crafted clarity it visually far outruns the ill-defined pen. With its size, weight and sharpness, the sword suggests more self-discipline and mental order in its bearer than any pen might afford, which is too often engaged in merely noting down whimsical movements of mental current in forms ranging from scratchy to mannered.

On the surface of the image, pen and sword share the same space, but beyond the rationale of the proposed comparison, which actually draws the argument into one of two courts (where, as we will see later, both parties are at home), another battleground is implied, which stays as empty as it is hidden. Here, logically speaking, the sword has to be fighting with another unmentioned sword in order to be making war. This way the sword is – so to speak: secretly – set up to display its inferiority to the pen; which in turn, firstly as a symbol of a higher order of abstraction, and secondly due to its greater proximity as the first-mentioned in this short and brutal piece of rhetoric, refers more easily and convincingly to an enveloping structure of safety and sense.

War, in this scenario, is denied any active role in the thinking, conscious persona, and conversely here, the thinking, rational persona is denied all the potency of the fight. The sentiment expressed here is a perfect example of the suppression mechanisms inherent in Western rationalism (‘Civilisation’): Making war, i.e. living out one’s ‘negative’ emotions on a non-intellectual stage – possibly even victoriously – is professedly barbaric, whereas to negate and suppress one’s emotions is constructed as a worthwhile and necessary endeavour. Even in a democratic system that purportedly aims to allow freedom of speech to everyone, there are these cultural limitations of emotional expression. This philosophy in practice may on the one hand be vital for the survival of our species, but the fact that it also provides the breeding ground for arguably the most perverted criminal offences on a daily basis (and has led to the creation of inarguably the most powerful weapons of mass destruction in human history), comes as no surprise when one contemplates how overpowering the restrictive reign of a rationalist culture over the hearts of its members has been. Imperatively, ‘the pen is mightier than the sword’ is voicing pure social conditioning: ‘Do not feel, upon failing at which (inevitable, unless you are dangerously deranged), at least stop yourself from acting on those feelings. Stay distracted, consume continuously according to pre-arranged patterns of perceived needs, and the state will cushion you from fearing death.’

It has become clear that, as a result of the immense complexities of our social, political and economic history, not only has the message of this sentence itself – like everything else in the cultural domain – had to change (hence the variety of possible and necessary contemporary readings), but so also has the sentiment that informed this message long vanished and been replaced by a range of new world views and belief systems. At present, what these generally have in common is that they sense themselves to be one of many possible views: heterogeneously scattered outside traditional hierarchies, others always requiring consideration.

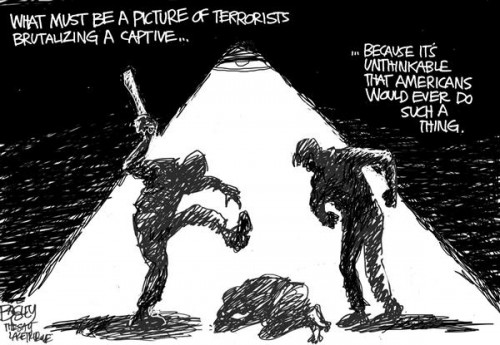

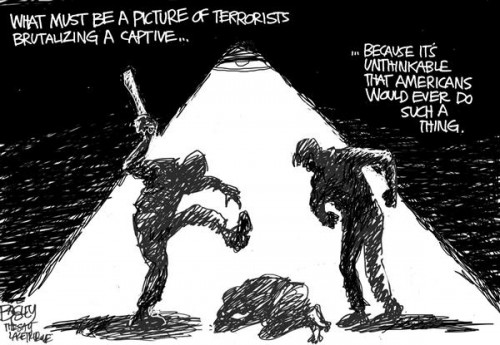

Of course there will always be fundamentalist and self-righteous tendencies in politics and other fields that need to set up an ‘other’ as opposite, with all the horrific consequences that ensue, as in the recent case of ordinary American country folk torturing and killing Iraqi prisoners of war in Abu Ghraib prison. The American defence minister’s public reasoning on this torture is that, far from being the carefully considered act of war between two nations that it was, it was supposedly a dirty deed carried out by rogue individuals. In the terminology of this text: that no ‘sword’ was involved. As a result of this denial the torturers will soon be publicly demonised and punished (under the same principle of othering), thereby serving as scapegoats for all those who have been actively involved in creating a lawless situation in these prisons in the first place. If the idea of a ‘mighty pen’ could be trusted to be referring to a positive pragmatism rather than a positivist idealism, it might now for example be able to symbolise an international military court, which could serve to address this new form of ideological and propagandist warfare. This kind of warfare is reminiscent of the public display of the severed heads of enemy soldiers in the Middle Ages, but it infinitely transcends it in calculation and coldness. That Iraqis are responding ‘in kind’ (with the recent public killing and burning of American tourists), surprises less than the Americans’ refusal to submit their soldiers to said international court of war.

Most people today do not believe that wars are stopped by anything somebody writes with a pen: In fact, we are becoming increasingly sensitised to the demagoguery of the media. The worst wars, the greatest weapons, the most inescapable conflicts, the most far-reaching crimes and deepest infringements of basic human rights are all created on paper, but they are rarely prevented and almost never undone again through the use of that medium.

Once ‘The pen is mightier than the sword’ may actually have been a revolutionary and powerful statement, but nowadays it is merely an overused turn of phrase that invites kitsch sentiments on the one hand and bitter cynicism on the other. Googling this phrase, one comes across fantasy websites, dating chatrooms, reactionary rants by fundamentalist Islamic school children, and all other kinds of intellectually ill-directed verbiage. This selection naturally also has to do with the medium of the internet, and only represents that quantity of writing that has made itself available to us as html code. On the other hand, if ‘mighty’ writing was as easily and readily available today as all that web and magazine copy that likes to borrow this phrase, there would probably be less disillusionment in the mind of today’s reader who comes across it.

Many readers today are not used to enjoying or savouring the tensions and creative spaces offered by a linguistic symbol – they seem to lack the ability to read symbols as such. This is best exemplified by the mass of websites containing most literal readings of the quote. Self-defence sites for women describe a variety of techniques for using a pen as a weapon; crime-writer blogs publish stories investigating the poisonous qualities of ink; ‘Dungeons and Dragons’-fans have ‘webrings’, where the interpretations voted into the top five all delight in ‘setting things right’: the pen would have to be very big and the sword very small… etc. Many readers who have enjoyed the privilege of being exposed to a variety of literary genres may shudder at the shallowness of this method of constructing linguistic communication, but recognising the widespread reality of this practice could also be a less prematurely judgmental process and even bear new creative fruit: new sets of immediately recognisable symbols are forming all the time, including all the potential pitfalls of more or less hidden reactionary sentiments, but far more open to widespread critical discussion.

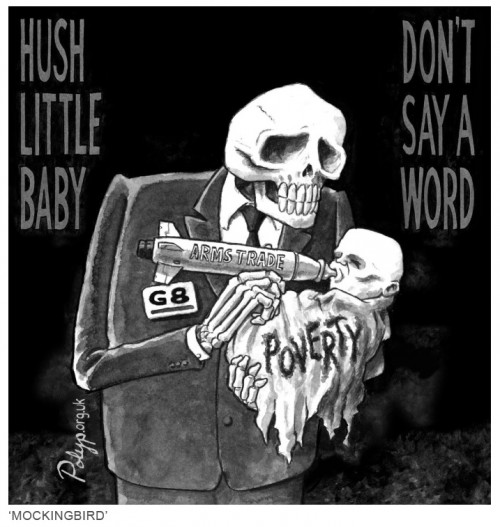

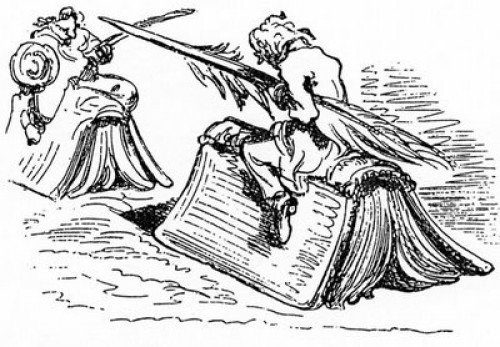

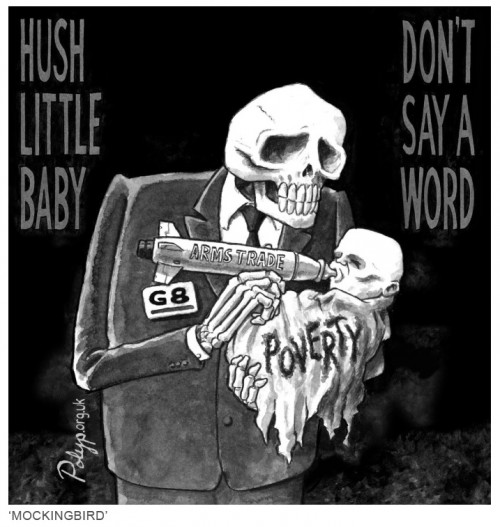

‘The sword is mightier than the pen’ – a statement that holds true, only rather less surprisingly so, which is why it is nowhere to be found as a quotation. What might have made the quote so long lasting is that it seems to be expressing something unthinkable: a pen battling with a sword and beating it, as it were: a poet wrestling down a soldier.

If, hypothetically unencumbered by any knowledge of the quote, a contemporary reader were to come across a sentence expressive of the negative ‘The pen is not mightier than the sword’, they might successfully be moved to contemplate the dynamics of power and information, and the worldwide imbalance regarding the privilege of acquiring knowledge. Installing this modified ‘quote’ publicly in the fashion of, for example, Jenny Holzer’s ‘Truisms’, may serve to draw attention to the Y-generation’s ubiquitous refusal to re-interpret and re-negotiate vital forms of human expression – a refusal structurally inherent in the banality of the practice of ‘sharing’ on (anti-)social networks, of regurgitating and replicating copies of once-historic fragments until the pen is dry.