Tag Archives: voice

jayne cortez – find your own voice (2010)

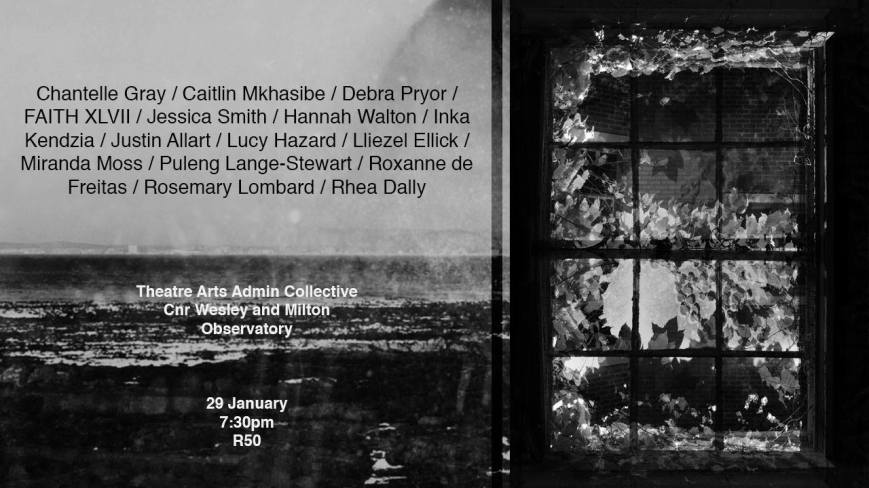

lliezel ellick, rosemary lombard & roxanne de freitas live at the window (2017)

Live non-verbal improvisation performed in absolute darkness, interacting with a cellphone recording from the day before, at The Window, an evening of experimental music, performance and visual art at the Theatre Arts Admin Collective, Observatory, Cape Town, 29 January 2017.

“It’s not easy to improvise… It’s the most difficult thing to do. Even when one improvises in front of a camera or microphone, one ventriloquizes or leaves another to speak in one’s place the schemas and languages that are already there. There are already a great number of prescriptions that are prescribed in our memory and in our culture. All the names are already pre-programmed. It’s already the names that inhibit our ability to ever really improvise. One can’t say what ever one wants, one is obliged more or less to reproduce the stereotypical discourse. And so I believe in improvisation and I fight for improvisation. But always with the belief that it’s impossible. And there where there is improvisation I am not able to see myself. I am blind to myself. And it’s what I will see, no, I won’t see it. It’s for others to see. The one who is improvised here… no, I won’t ever see him.”

— Jacques Derrida, unpublished interview, 1982, reproduced in David Toop’s Into the Maelstrom: Music, Improvisation and the Dream of Freedom: Before 1970, Bloomsbury, 2016, pg 21.

jenny hval – is there anything on me that doesn’t speak? (2013)

Off Innocence is Kinky (Rune Grammofon, 2013).

keening

We will be at The Window on Sunday. You have been warned.

the window – 29 january 2017

Join us! More details HERE. Dedicating my performance to Mark Fisher, who took his own life the other day. His brilliant work, particularly this blog post on hauntology, has been profoundly influential on how I understand archive and aspire to use sound. I’m so sad he is gone.

einstürzende neubauten – blume (1993)

Music video of the track from the album Tabula Rasa (1993, Mute Records), which pays clear visual homage to Luigi Russolo.

anna von hausswolff – evocation

From The Miraculous (Pomperipossa Records, out November 13th, 2015). Saw her live last week… Almost made my chest implode!

letta mbulu – mahlalela (lazy bones)

From Letta (1971, Chisa Records). Those first 35 seconds are everything.

rilke – from the first duino elegy

Isn’t it time that we lovingly freed ourselves from the beloved and,

Isn’t it time that we lovingly freed ourselves from the beloved and,

quivering, endured: as the arrow endures the bowstring’s tension,

so that gathered in the snap of release it can be more than itself?

For there is no place where we can remain.

Voices. Voices. Listen, my heart, as only saints have listened:

until the gigantic call lifted them off the ground;

yet they kept on, impossibly, kneeling and didn’t notice at all: so complete was their listening.

Not that you could endure God’s voice – far from it.

But listen to the voice of the wind and the ceaseless message that forms itself out of silence…

Of course, it is strange to inhabit the earth no longer,

to give up customs one barely had time to learn,

not to see roses and other promising Things in terms of a human future;

no longer to be what one was in infinitely anxious hands;

to leave even one’s own first name behind,

forgetting it as easily as a child abandons a broken toy.

Strange to no longer desire one’s desires.

Strange to see meanings that clung together once, floating away in every direction.

And being dead is hard work and full of retrieval before one can gradually feel a trace of eternity.

Though the living are wrong to believe in the too-sharp distinctions which

they themselves have created.

Angels (they say) don’t know whether it is the living they are moving among, or the dead.

The eternal torrent whirls all ages along in it, through both realms forever,

and their voices are drowned out in its thunderous roar.

sophie hunger – broken english

There were mountains to begin with

Silence shaped in giant

My voice would reach the highest

But you cannot tell this in English

An old man’s precise and attentive

My mother’s tongue my heart only sounds

As a girl I got lost in a cloud

But you cannot tell this in English

I balance an egg in a spoon

I’m never on time, it’s too late or too soon

In the night there is always the moon

That doesn’t speak in English

marie laforêt – la voix du silence

1966 Simon and Garfunkel cover.

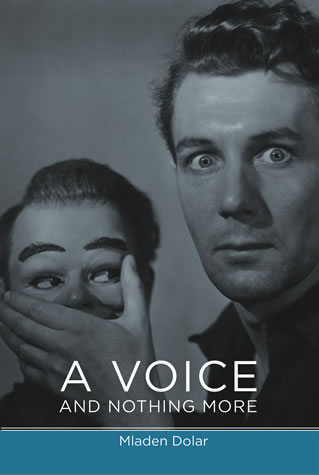

mladen dolar – his master’s voice

The following essay is excerpted from Mladen Dolar’s book, A Voice and Nothing More (which I’m reading for my dissertation).

The voice did not figure as a major [western] philosophical topic until the 1960s, when Derrida and Lacan separately proposed it as a central theoretical concern. Dolar goes beyond Derrida’s idea of “phonocentrism” and revives and develops Lacan’s claim that the voice is one of the paramount embodiments of the psychoanalytic object (objet a). Dolar proposes that, apart from the two commonly understood uses of the voice as a vehicle of meaning and as a source of aesthetic admiration, there is a third level of understanding: the voice as an object that can be seen as the lever of thought. He investigates the object voice on a number of different levels–the linguistics of the voice, the metaphysics of the voice, the ethics of the voice (with the voice of conscience), the paradoxical relation between the voice and the body, the politics of the voice–and he scrutinizes the uses of the voice in Freud and Kafka. (There’s a great review by Christine Boyko-Head HERE.)

—

Plutarch tells the story of a man who plucked a nightingale and finding but little to eat exclaimed: “You are just a voice and nothing more.”

Plutarch tells the story of a man who plucked a nightingale and finding but little to eat exclaimed: “You are just a voice and nothing more.”

There is a story that goes like this: In the middle of a war, in the middle of a battle, there is a company of Italian soldiers in the trenches. And there is an Italian commander who issues the command “Soldiers, attack!” But nothing happens, nobody moves. So the commander gets angry and shouts even louder “Soldiers, attack!” At which point there is a response, a voice rising from the trenches saying Che bella voce!

This story can serve as a good entry into the problem of the voice. On the first level this is a story of a failed interpellation. The soldiers fail to recognize themselves in the appeal, the call of the other, the call of duty, and they don’t act accordingly. Surely the fact that they are Italian soldiers plays a great role in it, they do act according to their image of not the most courageous soldiers in the world, as legend has it, and the story is most certainly not a model of political correctness, it indulges in tacit chauvinism and national stereotypes. So the command fails, the addressees don’t recognize themselves in the meaning being conveyed, they concentrate instead on the medium, which is the voice. The attention paid to the voice hinders the interpellation and the transmission of a symbolic mandate, the transmission of a mission.

But on a second level another interpellation works in the place of the failed one: if the soldiers don’t recognize themselves in their mission as the soldiers in the middle of a battle, they do recognize themselves as addressees of another message, they constitute a community as a response to the call, the community of people who can appreciate the aesthetics of a beautiful voice. Who can appreciate it when it is hardly the moment, and especially when it is hardly the moment to do so? So if in one respect they act as stereotypical Italian soldiers, they also act as stereotypical Italians in this other respect, namely as opera lovers. They constitute themselves as the community of “the friends of the Italian opera” (to take the immortal line from Some Like It Hot), living up to their reputation of connoisseurs, people of refined taste who have amply trained their ears with bel canto, so they can tell a beautiful voice when they hear one, even among the canon fire.

The soldiers have done the right thing, from our biased present perspective, at least in an incipient way, when they have concentrated on the voice instead of on the message, although, to be sure, for the wrong reasons. They are seized by a sudden aesthetic interest precisely when they would have had to attack, they concentrate on the voice because they have grasped the meaning all too well. But quite apart from their feigned artistic inclination they have also bungled the voice the moment they isolated it, they immediately turned it into an object of aesthetic pleasure, an object of veneration and worship, the bearer of a meaning beyond the ordinary meanings. The aesthetic concentration on the voice loses the voice precisely by turning it into a fetish-object.

I will try to argue that there is a third level: an object voice which doesn’t go up in smoke in conveyance of meaning and which doesn’t solidify either in an object of fetish reverence, but an object which functions as a blind spot in the call and a disturbance of aesthetic appreciation. One shows fidelity to the first by running to the attack, one shows fidelity to the second by running to the opera. But fidelity to the third is far more difficult to achieve. I will try to pursue it on three different levels: linguistics, ethics and politics. Continue reading

anna-maria hefele – polyphonic overtone singing

writing wrongs

my wrists ache

wrest them

look out

a deck of shards

sick notes

cutting in

cutting up

cutting down

cutting out

cutting off

the pulse

wound up wound

wind up wind

wound up wind

wound down wind

wind down wound

wind up wounded

binds unbound

an unstruck sound

this name means nothing to me

rolling off my glossed tongue

the missing ink

the beads of spittle in the pink

the drown flying in my drink

sink for yourself

sink or blink

outside carries on

the whorl of a banshee

howling at the pane

open your eyes

close your mouth

close your eyes

open your mouth

open your close

eye your mouth

mouth your silence

silence your eyes

make the whirl go away

angel olsen – stars

This is one of those songs I have tried to write myself… and then I hear somebody else already has it nailed so articulately. Sucks. In the best way possible.

I think you’d like to see me lose my mind

You treat me like a child; I’m angry, blind

I feel so much at once that I could scream

I wish I had the voice of everything

I wish I had the voice of everything

To scream the animals, to scream the earth

To scream the stars out of our universe

To scream it all back into nothingness

To scream the feeling ’til there’s nothing left

To scream the feeling ’til there’s nothing left

I’ll close my eyes

I’ll close my eyes and try to leave the world

Well you could change my mind with just a smile

And just before I turn to leave I think

I could use the thoughts you’ve given me

Oh I could use the thoughts you’ve given me

To sing the animals, to sing the earth

To sing the stars into a universe

To sing it all back into something new

To sing for life, or myself and maybe you

Wish I had the voice of everything, sometimes

Wish I had the voice of everything

busi mhlongo with madala kunene, rosebank, johannesburg, 1995

This fragment was filmed by Dick Jewell during the rehearsals for the recordings of Madala Kunene’s album Kon’ko Man in Johannesburg, 1995.

not demure enough, audrey!

sarah jaffe – summer begs

I fell into Sarah Jaffe down one of those magic late night Youtube rabbit holes a month or so ago… Such a lovely accident. This is off her 2010 album, Suburban Nature (on Kirtland Records).

ntozake shange – dark phrases

dark phrases of womanhood

of never havin been a girl

half-notes scattered

without rhythm/no tune

distraught laughter fallin

over a black girl’s shoulder

it’s funny/it’s hysterical

the melody-less-ness of her dance

don’t tell nobody don’t tell a soul

she’s dancin on beer cans & shingles

this must be the spook house

another song with no singers

lyrics/no voices

& interrupted solos

unseen performances

are we ghouls?

children of horror?

the joke?

don’t tell nobody don’t tell a soul

are we animals? have we gone crazy?

i can’t hear anythin

but maddening screams

& the soft strains of death

& you promised me

you promised me…

somebody/anybody

sing a black girl’s song

bring her out

to know herself

to know you

but sing her rhythms

carin/struggle/hard times

sing her song of life

she’s been dead so long

closed in silence so long

she doesn’t know the sound

of her own voice

her infinite beauty

she’s half-notes scattered

without rhythm/no tune

sing her sighs

sing the song of her possibilities

sing a righteous gospel

let her be born

let her be born

& handled warmly.

— from For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf. Macmillan Publishing, 1977. Shange was born Paulette L. Williams in Trenton, New Jersey. She later changed her name to isiXhosa/isiZulu – read more HERE.

nina simone – four women

Harlem Cultural Festival, 1969.

Thulani Davis writes of Nina Simone:

What Simone did for African American women was more liberating than the sweet elegance of her take on “I Love You, Porgy” (delivered without the fake dialect of all its predecessors), the thought-provoking militancy she added to spirituals like “Sinnerman,” or the wicked humor of “Old Jim Crow” and “Go Limp,” or the wonderfully ironic cover of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’s kitsch hit, “I Put a Spell on You.”

First of all, her songs, whether covers or original compositions, always privileged the black woman’s point of view; they spoke for the dispossessed Sister Sadie who cleaned floors or raised children who would never in their lives again treat black women with respect.

Yes, you lied to me all these years/told me to wash and clean my ears/and talk real fine, just like a lady/and you’d stop calling me Sister Sadie.

“See Line Woman” viewed its exotic black female as an object of desire and admiration in a way unknown outside of the black poetry that was its source, or those raunchy blues songs that polite Negroes did not play, which nonetheless lauded the virtues of a full body and brown skin.

My skin is black/My arms are long/My hair is wooly/My back is strong/Strong enough to take the pain/Inflicted again and again/What do they call me?/My name is Aunt Sara. — “Four Women”

It was “Four Women,” an instantly accessible analysis of the damning legacy of slavery, that made iconographic the real women we knew and would become. For African American women it became an anthem affirming our existence, our sanity, and our struggle to survive a culture which regards us as anti-feminine. It acknowledged the loss of childhoods among African American women, our invisibility, exploitation, defiance, and even subtly reminded that in slavery and patriarchy, your name is what they call you. Simone’s final defiant scream of the name Peaches was our invitation to get over color and class difference and step with the sister who said:

My skin is brown/My manner is tough/I’ll kill the first mother I see/ My life has been rough/I’m awfully bitter these days/Because my parents were slaves.

For African American women artists of my generation, “Four Women” became the core of works to come, notably Julie Dash’s film of the same name, and it should be regarded a direct ancestor of Ntozake Shange’s For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf. This Simone song was a call heard by Alice Walker, Toni Cade Bambara, Gayl Jones, and countless artists who come to mind as women who gave us a whole generation of the stories of Aunt Sara, Safronia, Sweet Thing, and Peaches.

May the High Priestess’s cult widen to take in the unwise who made her as outrageous as she was.

Read the rest of this article over at The Village Voice.

diamanda galas – a soul that’s been abused

Cover of the Ronnie Earl/Mighty Sam McClain blues/soul classic – this is a tremendous bootleg recorded on 24 October 2006 at Rio Theatre, Santa Cruz.

maria callas – mad scene from lucia di lammermoor (donizetti)

“The character of Lucia has become an icon in opera and beyond, an archetype of the constrained woman asserting herself in society. She reappears as a touchstone for such diverse later characters as Flaubert’s adulterous Madame Bovary and the repressed Englishwomen in the novels of E.M. Forster. The insanity that overtakes and destroys Lucia, depicted in opera’s most celebrated mad scene, has especially captured the public imagination. Donizetti’s handling of this fragile woman’s state of mind remains seductively beautiful, thoroughly compelling, and deeply disturbing. Madness as explored in this opera is not merely something that happens as a plot function: it is at once a personal tragedy, a political statement, and a healing ritual.” (Commentary from HERE)

Maria Callas performs “Il dolce suono mi colpì di sua voce”, the “Mad Scene” from the opera Lucia di Lammermoor by Gaetano Donizetti, recorded live in Florence in February 1953. Tullio Serafin conducted Callas, Giuseppe di Stefano, Tito Gobbi, Raffaele Arie, Valliano Natali, Maria Canali, Maggio Musical Fiorentino Orchestra & Maggio Musicale Fiorentino Chorus.

The discussion in the comments underneath the video is quite entertaining, especially if read in light of the Anne Carson essay I posted earlier. Continue reading

anne carson – the gender of sound

Madness and witchery as well as bestiality are conditions commonly associated with the use of the female voice in public, in ancient as well as modern contexts. Consider how many female celebrities of classical mythology, literature and cult make themselves objectionable by the way they use their voice.

For example, there is the heart-chilling groan of the Gorgon, whose name is derived from a Sanskrit word, *garg meaning “a guttural animal howl that issues as a great wind from the back of the throat through a hugely distended mouth”. There are the Furies whose high-pitched and horrendous voices are compared by Aiskhylos to howling dogs or sounds of people being tortured in hell (Eumenides). There is the deadly voice of the Sirens and the dangerous ventriloquism of Helen (Odyssey) and the incredible babbling of Kassandra (Aiskhylos, Agamemnon) and the fearsome hullabaloo of Artemis as she charges through the woods (Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite). There is the seductive discourse of Aphrodite which is so concrete an aspect of her power that she can wear it on her belt as a physical object or lend it to other women (Iliad). There is the old woman of Eleusinian legend Iambe who shrieks obscenities and throws her skirt up over her head to expose her genitalia. There is the haunting garrulity of the nymph Echo (daughter of Iambe in Athenian legend) who is described by Sophokles as “the girl with no door on her mouth” (Philoktetes).

Putting a door on the female mouth has been an important project of patriarchal culture from antiquity to the present day. Its chief tactic is an ideological association of female sound with monstrosity, disorder and death.

— From “The Gender of Sound”, in Glass, Irony and God. New Directions, 1995: pp 120-121

The brilliant Anne Carson presents a history of the gendered voice, from Sophocles to Gertrude Stein. She outlines what is at stake in our assumptions around sound, questioning whether the concept of ‘self-control’ is a barrier to acknowledging other forms of human order, feeding into wider debates on social order, both past and present.

Read the whole essay HERE.

malala yousafzai on being silenced

ani difranco on exploitation of young women

An excerpt from a 2007 interview with Ani DiFranco where she speaks about life as a teenager, anger, rape and exploitation, and on finding the tools to stand up for yourself in a world where you don’t feel respected. If you want to watch the whole interview, there are 5 parts on Youtube.

louise gluck – time

There was too much, always, then too little.

Childhood: sickness.

By the side of the bed I had a little bell —

at the other end of the bell, my mother.

Sickness, gray rain. the dogs slept through it. They slept on the bed,

at the end of it, and it seemed to me they understood

about childhood: best to remain unconscious.

The rain made gray slats on the windows.

I sat with my book, the little bell beside me.

Without hearing a voice, I apprenticed myself to a voice.

Without seeing any sign of the spirit, I determined

to live in the spirit.

The rain faded in and out.

Month after month, in the space of a day.

Things became dreams; dreams became things.

Then I was well; the bell went back to the cupboard.

The rain ended. The dogs stood at the door,

panting to go outside.

I was well, then I was an adult.

And time went on — it was like the rain,

so much, so much, as though it was a weight that couldn’t be moved.

I was a child, half sleeping.

I was sick; I was protected.

And I lived in the world of the spirit,

the world of gray rain,

the lost, the remembered.

Then suddenly the sun was shining.

And time went on, even when there was almost none left.

And the perceived became the remembered,

the remembered, the perceived.

__

From The Seven Ages (Ecco/Harper Collins, 2001)

kim gordon & ikue mori – la casa encendida

Live performance, 28 July 2012, Madrid.

“i will never forget how to dance”

I have been working for the last while as researcher and production manager on a weekly SABC-commissioned TV documentary series, I Am Woman – Leap of Faith. Here’s one of the episodes, directed by Jane Kennedy:

In January 1996 Shelley Barry was 23 and on her way to a job interview in Cape Town when she was caught in the crossfire of taxi violence caused by rival taxi groups battling for ownership of the same routes.

She was sitting next to the taxi driver in the front of his minibus when an assassin pulled up alongside the moving vehicle and opened fire. The driver was shot seven times and was killed instantly. The taxi crashed, injuring many of its passengers.

Shelley was hit by one of the assassin’s bullets and was instantly paralysed. Her life hung in the balance and it was assumed she would not survive. The friend she was travelling with was seriously injured but has recovered, despite the bullet still lodged in her chest. Shelley has been in a wheelchair ever since. Today she is 42.

How does one create a life for oneself after something like this? How does one find work and meaning once again? Importantly, what happened to Shelley Barry’s dream, held close since childhood, of becoming a filmmaker?

Join this remarkable woman, teacher, activist and filmmaker as she describes her life before and after the shooting: The life of a young girl who told her childhood friends that one day her films would be on the big screen and has achieved that, despite a bullet getting in her way and forcing her into a wheelchair for over twenty years… The life of an activist who worked in the Presidency and has made a significant difference to the lives of the disabled in South Africa… The deeply spiritual journey of a sensitive, funny and bolshy woman who, despite her circumstances, is determined to continue making her mark on the world.

Shelley Barry graciously lets us into her world, describing the many Leaps of Faith she has taken so far and continues to take each and every day.

Catch the broadcast of this programme on SABC 3, Sundays at 09h30, or watch archived episodes on the I AM WOMAN – LEAP OF FAITH WEBSITE.

erik bünger’s schizophonia

I watched two incredible films tonight, Schizophonia and The Third Man, courtesy of Anette Hoffmann and the Archive & Public Culture Platform at UCT, with the kind permission of musician, composer and performance artist, Erik Bünger, who made the films.

In each film, Bünger both analyses and plays with the uncanny, magical potency of sound as recorded medium. Everything he does is underpinned by formidable quantities of research, a fondness for outrageously rhizomatic linkages and a wicked sense of humour. Definitely my new art crush of the month! ;)

Here’s a video of Bünger giving a lecture/performance which utilises much of the material presented in the standalone film, Schizophonia. This was recorded at MEDEA, Malmo University, in March 2011, as part of the K3 courses “Music in the Digital Media Landscape” and “Illustrating with Music”.

I really WISH I could find more of The Third Man to share here – it was tremendously entertaining, and, even off on its most questionable, occult-paranoid tangents, bizarrely pertinent to so much of the stuff about performance, recording and playback of music that I’ve been posting and thinking about in the past few years; even down to an hilarious discussion of the “entraining” (his word) power of The Sound Of Music (my post this afternoon prefigured this too, eerily!).

Anyway, you can watch the lecture:

And here’s a bio:

The Swedish artist, composer, musician and writer Erik Bünger (1976) works with re-contextualising existing media in performances, installations and web projects. In ‘Gospels’, sections of Hollywood interviews are removed from their original contexts, interacting to form a new, seemingly coherent whole. Yet these pre-existing works frequently conflict; Bünger explores the disjunction between replaying and experiencing in his ‘Lecture on Schizophonia’. This simultaneously analytical and performative work highlights the relationship between sound and perceived reality, using popular references and familiar footage including Barak Obama and Woody Allen. Similar tensions are exposed in ‘God Moves on the Water’, in which two songs about the sinking of the Titanic are combined to form a third narrative. In ‘The Third Man’, the negative power of music is explored. Displacing and recombining familiar material, Bünger challenges the separation between authentic and simulated experiences.

Bünger may have followed a traditional education in composition at the Stockholm Royal College of Music, but he is hardly a run-of-the-mill composer. His works have increasingly come to approach contemporary conceptual art, but his combination of sound and visual is also linked to literary storytelling. In his performances, installations and web projects, different timelines are superposed, past worlds and present understandings. The most important thing about Bünger’s work is not the art or literature context but the transformation that takes place in the specific works. What may seem trivial and inconsequential suddenly becomes the stuff of dreams. He is attracted to moments when recorded sound and image bridge a space between absolutes, between death and life and between gods and humankind. –

This info comes from http://expo.argosarts.org/