Category Archives: art

like a bosch

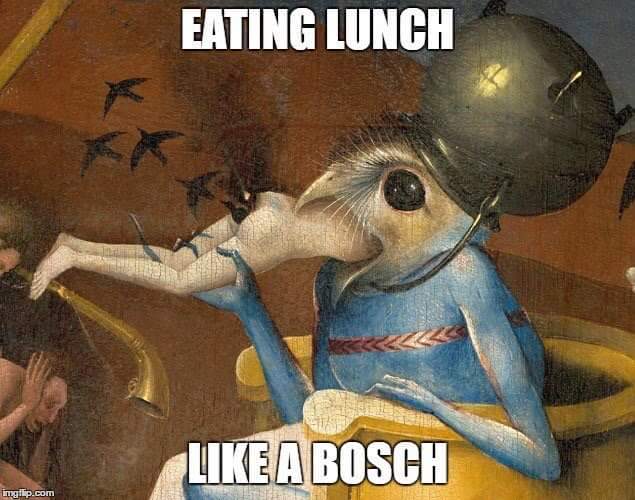

klimt eastwood

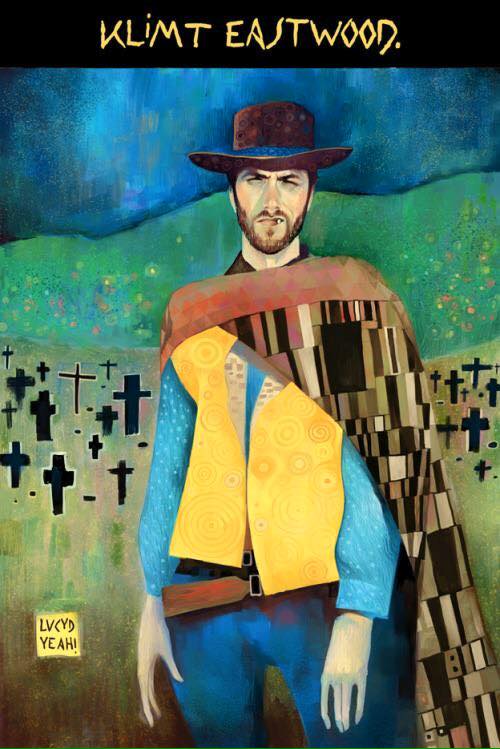

andre breton – nadja (1928)

The narrator, named André, ruminates on a number of Surrealist principles, before ultimately commencing (around a third of the way through the novel) on a narrative account, generally linear, of his brief ten day affair with the titular character Nadja. She is so named “because in Russian it’s the beginning of the word hope, and because it’s only the beginning,” but her name might also evoke the Spanish “Nadie,” which means “No one.” The narrator becomes obsessed with this woman with whom he, upon a chance encounter while walking through the street, strikes up conversation immediately. He becomes reliant on daily rendezvous, occasionally culminating in romance (a kiss here and there).

His true fascination with Nadja, however, is her vision of the world, which is often provoked through a discussion of the work of a number of Surrealist artists, including himself. While her understanding of existence subverts the rigidly authoritarian quotidian, it is later discovered that she is mad and belongs in a sanitarium. After Nadja reveals too many details of her past life, she in a sense becomes demystified, and the narrator realises that he cannot continue their relationship.

In the remaining quarter of the text, André distances himself from her corporeal form and descends into a meandering rumination on her absence, so much so that one wonders if her absence offers him greater inspiration than does her presence. It is, after all, the reification and materialisation of Nadja as an ordinary person that André ultimately despises and cannot tolerate to the point of inducing tears.

There is something about the closeness once felt between the narrator and Nadja that indicated a depth beyond the limits of conscious rationality, waking logic, and sane operations of the everyday. There is something essentially “mysterious, improbable, unique, bewildering” about her; this reinforces the notion that their propinquity serves only to remind André of Nadja’s impenetrability.

Her eventual recession into absence is the fundamental concern of this text, an absence that permits Nadja to live freely in André’s conscious and unconscious, seemingly unbridled, maintaining her paradoxical role as both present and absent. With Nadja’s past fixed within his own memory and consciousness, the narrator is awakened to the impenetrability of reality and perceives a particularly ghostly residue peeking from under its thin veil. Thus, he might better put into practice his theory of Surrealism, predicated on the dreaminess of the experience of reality within reality itself.

Read the book here: Andre Breton – Nadja.

walter benjamin – surrealism: the last snapshot of the european intelligentsia (1929)

… There is always, in such movements, a moment when the original tension of the secret society must either explode in a matter-of-fact, profane struggle for power and domination, or decay as a public demonstration and be transformed. Surrealism is in this phase of transformation at present. But at the time when it broke over its founders as an inspiring dream wave, it seemed the most integral, conclusive, absolute of movements. Everything with which it came into contact was integrated. Life only seemed worth living where the threshold between waking and sleeping was worn away in everyone as by the steps of multitudinous images flooding back and forth, language only seemed itself where, sound and image, image and sound interpenetrated with automatic precision and such felicity that no chink was left for the penny-in-the-slot called ‘meaning’.

Image and language take precedence. Saint-Pol Roux, retiring to bed about daybreak, fixes a notice on his door: ‘Poet at work.’ Breton notes: ‘Quietly. I want to pass where no one yet has passed, quietly! After you, dearest language.’ Language takes precedence. Not only before meaning. Also before the self. In the world’s structure dream loosens individuality like a bad tooth. This loosening of the self by intoxication is, at the same time, precisely the fruitful, living experience that allowed these people to step outside the domain of intoxication.

This is not the place to give an exact definition of Surrealist experience. But anyone who has perceived that the writings of this circle are not literature but something else – demonstrations, watchwords, documents, bluffs, forgeries if you will, but at any rate not literature – will also know, for the same reason, that the writings are concerned literally with experiences, not with theories and still less with phantasms. And these experiences are by no means limited to dreams, hours of hashish eating, or opium smoking. It is a cardinal error to believe that, of ‘Surrealist experiences’, we know only the religious ecstasies or the ecstasies of drugs. The opium of the people, Lenin called religion, and brought the two things closer together than the Surrealists could have liked.

I shall refer later to the bitter, passionate revolt against Catholicism in which Rimbaud, Lautreamont, and Apollinaire brought Surrealism into the world. But the true creative overcoming of religious illumination certainly does not lie in narcotics. It resides in a profane illumination, ‘a materialistic, anthropological inspiration, to which hashish, opium, or whatever else can give an introductory lesson. (But a dangerous one; and the religious lesson is stricter.)

This profane illumination did not always find the Surrealists equal to it, or to themselves, and the very writings that proclaim it most powerfully, Aragon’s incomparable Paysan de Paris and Breton’s Nadja, show very disturbing symptoms of deficiency. For example, there is in Nadja an excellent passage on the ‘delightful days spent looting Paris under the sign of Sacco and Vanzetti’; Breton adds the assurance that in those days Boulevard Bonne-Nouvelle fulfilled the strategic promise of revolt ‘that had always been implicit in its name. But Madame Sacco also appears, not the wife of Fuller’s victim but avoyante, a fortune-teller who lives at 3 rue des Usines and tells Paul Eluard that he can expect no good from Nadja.

Now I concede that the breakneck career of Surrealism over rooftops, lightning conductors, gutters, verandas, weathercocks, stucco work – all ornaments are grist to the cat burglar’s mill- may have taken it also into the humid backroom of spiritualism. But I am not pleased to hear it cautiously tapping on the window-panes to inquire about its future. Who would not wish to see these adoptive children of revolution most rigorously severed from all the goings-on in the conventicles of down-at-heel dowagers, retired majors, and emigre profiteers?

In other respects Breton’s book illustrates well a number of the basic characteristics of this ‘profane illumination’. He calls Nadja ‘a book with a banging door’. (In Moscow I lived in a hotel in which almost all the rooms were occupied by Tibetan lamas who had come to Moscow for a congress of Buddhist churches. I was struck by the number of doors in the corridors that were always left ajar. What had at first seemed accidental began to be disturbing. I found out that in these rooms lived members of a sect who had sworn never to occupy closed rooms. The shock I had then must be felt by the reader of Nadja.)

To live in a glass house is a revolutionary virtue par excellence. It is also an intoxication, a moral exhibitionism, that we badly need. Discretion concerning one’s own existence, once an aristocratic virtue, has become more and more an affair of petty-bourgeois parvenus. Nadja has achieved the true, creative synthesis between the art novel and the roman-a-clef.

Moreover, one need only take love seriously to recognize in it, too – as Nadja also indicates – a ‘profane illumination’. ‘At just that time’ (i.e., when he knew Nadja), the author tells us, ‘I took a great interest in the epoch of Louis VII, because it was the time of the ‘courts of love’, and I tried to picture with great intensity how people saw life then.’ We have from a recent author quite exact information on Provencal love poetry, which comes surprisingly close to the Surrealist conception of love. ‘All the poets of the ‘new style’,’ Erich Auerback points out in his excellent Dante: Poet of the Secular World, ‘possess a mystical beloved, they all have approximately the same very curious experience of love; to them all Amor bestows or withholds gifts that resemble an illumination more than sensual pleasure; all arc subject to a kind of secret bond that determines their inner and perhaps also their outer-lives’. The dialectics of intoxication are indeed curious. Is not perhaps all ecstasy in one world humiliating sobriety in that complementary to it? What is it that courtly Minne seeks, and it, not love, binds Breton to the telepathic girl, if not to make chastity, too, a transport? Into a world that borders not only on tombs of the Sacred Heart or altars to the Virgin, but also on the morning before a battle or after a victory.

The lady, in esoteric love, matters least. So, too, for Breton. He is closer to the things that Nadja is close to than to her. What are these things? Nothing could reveal more about Surrealism than their canon.Where shall I begin? He can boast an extraordinary discovery. He was the first to perceive the revolutionary energies that appear in the ‘outmoded’, in the first iron constructions, the first factory buildings, the earliest photos, the objects that have begun to be extinct, grand pianos, the dresses of five years ago, fashionable restaurants when the vogue has begun to ebb from them. The relation of these things to revolution, no one can have a more exact concept of it than these authors. No one before these visionaries and augurs perceived how destitution – not only social but architectonic, the poverty of interiors/enslaved and enslaving objects – can be suddenly transformed into revolutionary nihilism. Leaving aside Aragon’s Passage de I’Opera, Breton and Nadja are the lovers who convert everything that we have experienced on mournful railway journeys (railways are beginning to age), on Godforsaken Sunday afternoons in the proletarian quarters of the great cities, in the first glance through the rain-blurred window of a new apartment, into revolutionary experience, if not action. They bring the immense forces of ‘atmosphere’ concealed in these things to the point of explosion. What form do you suppose a life would take that was determined at a decisive moment precisely by the street song last on everyone’s lips?walter benjamin on reading, telepathy, magic

Near the end of his 1929 essay on surrealism, Walter Benjamin suggests a connection between investigations into reading and into telepathic phenomena, a theme he returns to again, in the context of reading and more ancient traditions of magic, in his 1933 essay “Doctrine of the Similar.” This connection he suggests between reading practices and the occult is a profound one, both historically and for Benjamin’s own time and work, and not just in terms of telepathy. Some of the earliest practices of reading were not of letters, words, or books, but of stars, entrails, and birds, and these practices had a significant impact on the way reading was understood in the ancient world. And the relations between such ancient magic and reading were still (or again) of crucial importance to the modernists of the early twentieth century, including Benjamin and his sustained interest in what he called ‘das magische Lesen.’

What I will present here is part of a larger project devoted to tracing out the more salient connections in both the ancient and modern worlds between the practices of reading and of magic, and particularly those of magic most closely aligned with practices of divination. I choose to concentrate on those aspects of magic most associated with divination because these seem historically most associated with the reading of both literature and the world, and because I believe that tracing out the often ignored genealogy of this future or fortune-telling aspect of reading reveals one of the most fascinating chapters in the modern reception of antiquity.

Read the whole paper: Eric Downing – Divining Benjamin – Reading Fate, Graphology, Gambling

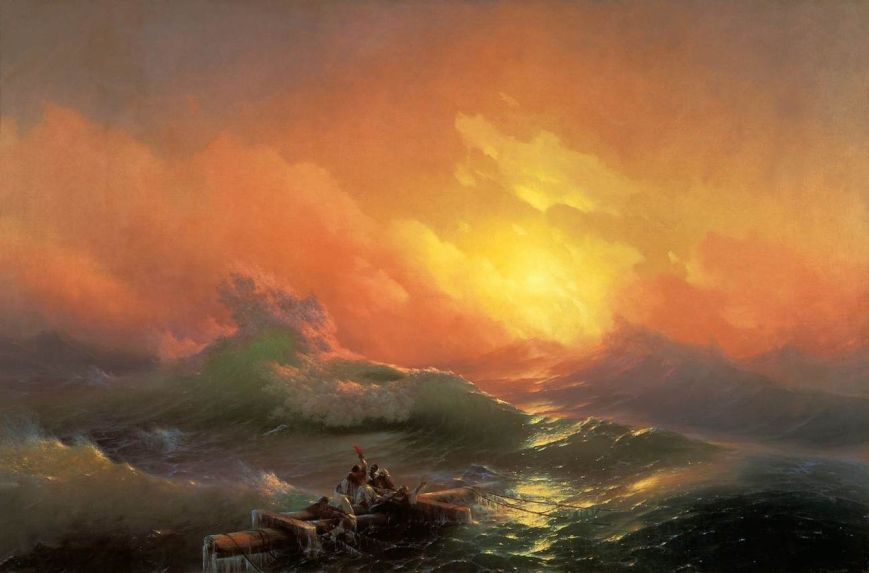

ivan aivazovsky – the ninth wave (1850)

grimes – flesh without blood/life in the vivid dream (2015)

“I could live in the world just like a stranger

I could tell you the truth or a lie

I could tell you that people are good in the end

But why, why would I?

Angels will cry when it’s raining

Tears that are no longer clean…”

From Art Angels (2015), available for download here. Written, directed, edited, coloured and art directed by Grimes.

And HERE is an interview with her.

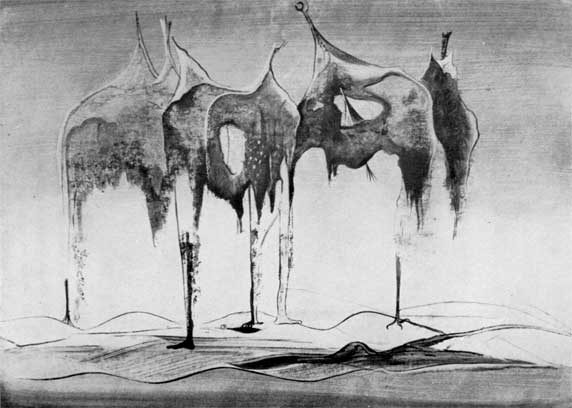

paul celan – edgar jené and the dream about the dream (1948)

I am supposed to tell you some of the words I heard deep down in the sea where there is so much silence and so much happens. I cut my way through the objects and objections of reality and stood before the sea’s mirror surface. I had to wait until it burst open and allowed me to enter the huge crystal of the inner world. With the large lower star of disconsolate explorers shining above me, I followed Edgar Jené beneath his paintings.

Though I had known the journey would be strenuous, I worried when I had to enter one of the roads alone, without a guide. One of the roads! There were innumerable, all inviting, all offering me different new eyes to look at the beautiful wilderness on the other, deeper side of existence. No wonder that, in this moment when I still had my own stubborn old eyes, I tried to make comparisons in order to be able to choose. My mouth, however, placed higher than my eyes and bolder for having often spoken in my sleep, had moved ahead and mocked me: ‘Well, old identity monger, what did you see and recognize, you brave doctor of tautology? What could you recognize, tell me, along this unfamiliar road? An also-tree or almost-tree, right? And now you are mustering your Latin for a letter to old Linnaeus? You had better haul up a pair of eyes from the bottom of your soul and put them on your chest: then you’ll find out what is happening here.’

Now I am a person who likes simple words. It is true, I had realised long before this journey that there was much evil and injustice in the world I had now left, but I had believed I could shake the foundations if I called things by their proper names. I knew such an enterprise meant returning to absolute naïveté. This naïveté I considered as a primal vision purified of the slag of centuries of hoary lies about the world. I remember a conversation with a friend about Kleist’s Marionette Theatre. How could one regain that original grace, which would become the heading of the last and, I suppose, loftiest chapter in the history of mankind?

It was, my friend held, by letting reason purify our unconscious inner life that we could recapture the immediacy of the beginning – which would in the end give meaning to our life and make it worth living. In this view, beginning and end were one, and a note of mourning for original sin was struck. The wall which separates today from tomorrow must be torn down so that tomorrow could again be yesterday. But what must we actually do now, in our own time, to reach timelessness, eternity, the marriage of tomorrow-and-yesterday? Reason, he said, must prevail. A bath in the aqua regia of intelligence must give their true (primitive) meaning back to words, hence to things, beings, occurrences. A tree must again be a tree, and its branch, on which the rebels of a hundred wars have been hanged, must again flower in spring.

Here my first objection came up. It was simply this: I knew that anything that happened was more than an addition to the given, more than an attribute, more or less difficult to remove from the essence, that it changed the essence in its very being and thus cleared the way for ceaseless transformation.

My friend was stubborn. He claimed that even in the stream of human evolution he could distinguish the constants of the soul, know the limits of the unconscious. All we needed was for reason to go down into the deep and haul the water of the dark well up to the surface. This well, like any other, had a bottom one could reach, and if only the surface were ready to receive the water from the deep, the sun of justice shining, the job would be done. But how can we ever succeed, he said, if you and people like you never come out of the deep, never stop communing with the dark springs?

I saw that this reproach was aimed at my professing that, since we know the world and its institutions are a prison for man and his spirit, we must do all we can to tear down its walls. At the same time, I saw which course this knowledge prescribed. I realised that man was not only languishing in the chains of external life, but was also gagged and unable to speak – and by speaking I mean the entire sphere of human expression – because his words (gestures, movements) groaned under an age-old load of false and distorted sincerity. What could be more dishonest than to claim that words had somehow, at bottom, remained the same! I could not help seeing that the ashes of burned-out meanings (and not only of those) had covered what had, since time immemorial, been striving for expression in man’s inner most soul.

How could something new and pure issue from this? It may be from the remotest regions of the spirit that words and figures will come, images and gestures, veiled and unveiled as in a dream. When they meet in their heady course, and the spark of the wonderful is born from the marriage of strange and most strange, then I will know I am facing the new radiance. It will give me a dubious look because, even though I have conjured it up, it exists beyond the concepts of my wakeful thinking; its light is not daylight; it is inhabited by figures which I do not recognise, but know at first sight. Its weight has a different heaviness, its colour speaks to the new eyes which my closed lids have given one another; my hearing has wandered into my fingertips and learns to see; my heart, now that it lives behind my forehead, tastes the laws of a new, unceasing, free motion. I follow my wandering senses into this new world of the spirit and come to know freedom. Here, where I am free, I can see what nasty lies the other side told me. Continue reading

essential diversions

Art by Zara Moon Arthur.

his arrival was foretold in the ancient murals

lou reed – street hassle

melati suryodarmo – “exergie – butter dance”

Lilith Performance Studio, June 5, 2010

Melati Suryodarmo (b. in 1969 in Surakarta, Indonesia, lives and works in Braunschweig, Germany) performs EXERGIE – Butter dance, an older piece but shown for the first time at Lilith.

20 blocks of butter in a square on the black dance carpet. Suryodarmo enters the space, dressed in a black tight dress and red high heels. She steps on the pieces of butter. She starts to dance to the sound of Indonesian shamanistic drums. She dances and falls, hitting the floor hard, rising, and continuously being on the verge of standing, slipping and falling in the butter. After twenty minutes Suryodarmo rises one last time, covered in butter, and leaves the space.

http://www.melatisuryodarmo.com/

Copyright of the performance: Melati Suryodarmo

Documentation done by Lilith Performance Studio.

Copyright of the documentation belongs to Melati Suryodarmo and Lilith Performance Studio, Malmo, Sweden.

jeannette ehlers – whip it good

This is an incredibly powerful performance.

Performances took place 24 – 30 April 2015, presented by Autograph ABP at Rivington Place, London. Presented in two parts, seven evening performances in the gallery followed by a seven-week exhibition, ‘Whip it Good’ retraces the footsteps of colonialism and maps the contemporary reverberations of the triangular slave trade via a series of performances that will result in a body of new ‘action’ paintings.

During each performance, the artist radically transforms the whip – a potent sign and signifier of violence against the enslaved body – into a contemporary painting tool, evoking within both the spectators and the participants the physical and visceral brutality of the transatlantic slave trade. Deep black charcoal is rubbed into the whip, directed at a large-scale white canvas, and – following the artist’s initial ritual – offered to members of the audience to complete the painting.

However, the themes that emerge from Whip It Good trace beyond those of slavery: Ehlers’ actions powerfully disrupt historical relationships between agency and control in the contemporary. The ensuing ‘whipped’ canvases become transformative bearers of the historical legacy of imperial violence, and through a controversial artistic act re-awaken critical debates surrounding gender, race and power within artistic production. What the process generates for the artist, is an intensely focused space in which to make new work as part of a cathartic collaborative process.

Read Chandra Frank’s review of the performance, which also took place in Gallery Momo in South Africa, HERE.

rosaleen ryan – the birth of suburbia

david bowie – lazarus

I was listening to David Bowie’s brand new album last night, thinking about how much I still love him. I can’t even begin to engage with how important Bowie and his work have been to me since I was a very young teenager. It’s washing over me in waves.

He felt like my guardian angel at times, transcending the vulgarity of the mundane, making alienation tangible and difference something to celebrate wildly… How strange to think of him as mortal.

Sayonara, Starman. What a gut-wrenchingly perfect exit.

tanz den untergang mit mir

siri karlsson – när mörkret faller

laurie anderson’s new film, “heart of a dog”

“And finally I saw it: the connection between love and death, and that the purpose of death is the release of love.”

Here is a review, and here is the trailer for Laurie Anderson’s new film, Heart of a Dog, which premiered in September. I really hope I get to see it somewhere on a big screen.

Here is a review, and here is the trailer for Laurie Anderson’s new film, Heart of a Dog, which premiered in September. I really hope I get to see it somewhere on a big screen.

And Robert Christgau had this to say about the soundtrack:

The soundtrack to a film I missed is also Anderson’a simplest and finest album, accruing power and complexity as you relisten and relisten again: 75 minutes of sparsely but gorgeously and aptly orchestrated tales about a) her beloved rat terrier Lolabelle and b) the experience of death. There are few detours—even her old fascination with the surveillance state packs conceptual weight. Often she’s wry, but never is she satiric; occasionally she varies spoken word with singsong, but never is her voice distorted. She’s just telling us stories about life and death and what comes in the middle when you do them right, which is love.

There’s a lot of Buddhism, a lot of mom, a whole lot of Lolabelle, and no Lou Reed at all beyond a few casual “we”s. Only he’s there in all this love and death talk—you can feel him. And then suddenly the finale is all Lou, singing a rough, wise, abstruse song about the meaning of love that first appeared on his last great album, Ecstasy—a song that was dubious there yet is perfect here. One side of the CD insert is portraits of Lolabelle. But on the other side there’s a note: “dedicated to the magnificent spirit/of my husband, Lou Reed/1942-2013.” I know I should see the movie. But I bet it’d be an anticlimax. A PLUS

EDIT 6/11/15. And here’s a beautiful interview with Anderson about the film:

a luta continua

totte leker med kisse

I can’t think of a better way to start understanding a country’s culture and mores than by watching its kids’ programmes (also, the simple language is good when you’re just starting to learn). The cat in this is so beautifully rendered. It teaches gentleness and consideration for others. What is weird, though, is that only the invisible narrator has a voice, although there is other diegetic sound. It’s very clearly meant to be didactic, like the voice of the superego.

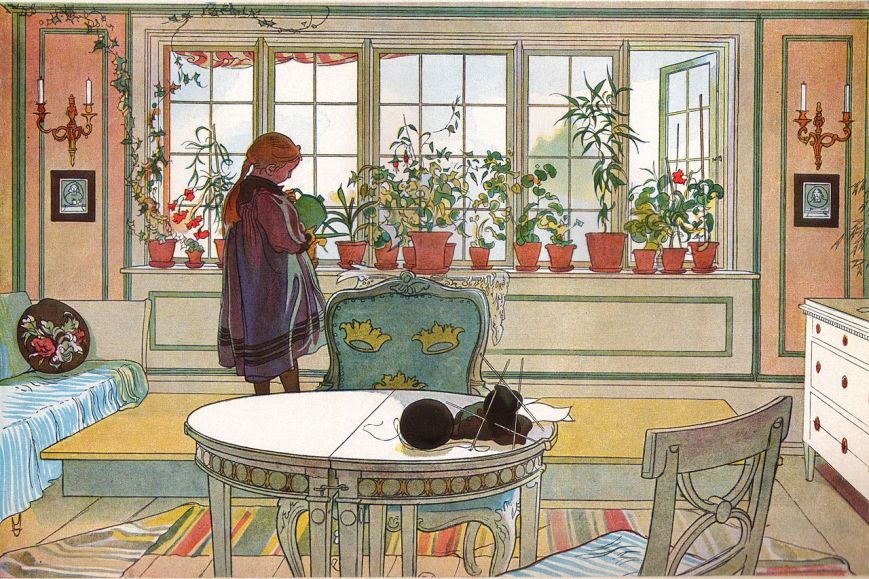

carl larsson – blomsterfönstret (1894)

A watercolour from the book “Ett Hem” (A Home). More about Carl Larsson HERE. This is a painting of a room in the Larssons’ home that exists to this day, decorated exactly the same, in Sundborn, about 11 km from where I am living.

the amen break – a documentary

Utterly fascinating documentary on the use of the “Amen Break”, sampled from The Winston’s 1969 soul record, “Amen Brother” (although the narrator has the most boring voice ever, and the images shown are really pointless – it’s actually an audio documentary), looking at the intersection of technology, creativity and copyright.

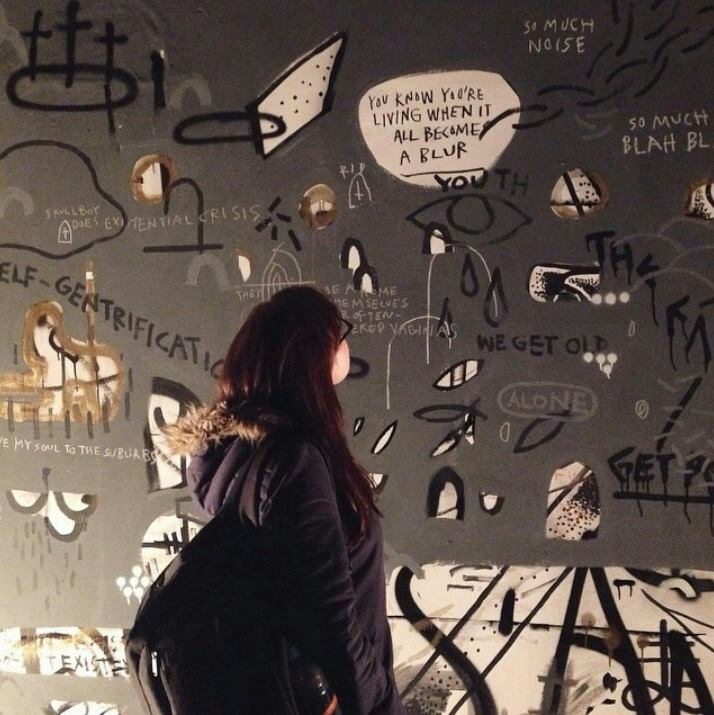

woodstock, june 2015

More Skullboy HERE.

modern lovers – pablo picasso

The white geek entitlement blues. ;)

blue moon

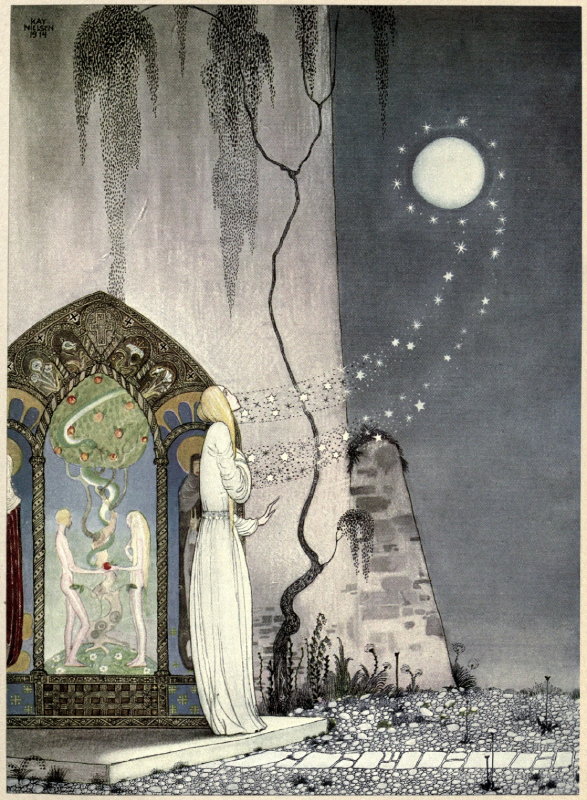

Kay Nielsen, 1914. Illustration from ‘East of the Sun and West of the Moon: Old Tales from the North’.

Check out the whole book at Project Gutenberg.

the vacillating liberal

head in the clouds

“Destinations is an ongoing series of self-portraits inspired by the decision to explore on one’s own. Over the past few years I have often felt compelled to travel alone, trusting in the direction of my curiosities and finding inspiration in the experiences that follow. Some of these images were conceptualized beforehand where others were created completely on impulse, reflecting a documentation of my surroundings, mindset, and subconscious. With my face hidden the girl becomes unidentifiable – allowing others to interpret the images as they will; incorporating their own journey and experiences.”

More of this series HERE.

ana teresa barboza vs. alysha speer

Life is painful and messed up. It gets complicated at the worst of times, and sometimes you have no idea where to go or what to do. Lots of times people just let themselves get lost, dropping into a wide open, huge abyss. But that’s why we have to keep trying. We have to push through all that hurts us, work past all our memories that are haunting us. Sometimes the things that hurt us are the things that make us strongest. A life without experience, in my opinion, is no life at all. And that’s why I tell everyone that, even when it hurts, never stop yourself from living.

― Alysha Speer

Check out more of Peruvian artist Ana Teresa Barboza’s fascinating embroidery work previously featured on Fleurmach, or on her own blog, HERE.

![Max Ernst - Une semaine de bonté [A Week of Kindness]. La clé des chants 1 [The Key of Songs 1] 1933](https://fleurmach.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/003_max_ernst_theredlist.jpg?w=869)