Tag Archives: patriarchy

laurie penny – cybersexism: sex, gender and power on the internet (2013)

‘In ye olden tymes of 1987, the rhetoric was that we would change genders the way we change underwear,’ says Clay Shirky, media theorist and author of Here Comes Everybody.‘[But] a lot of it assumed that everyone would be happy passing as people like me – white, straight, male, middle-class and at least culturally Christian.’ Shirky calls this ‘the gender closet’: ‘people like me saying to people like you, “You can be treated just like a regular normal person and not like a woman at all, as long as we don’t know you’re a woman.”’

The Internet was supposed to be for everyone… Millions found their voices in this brave new online world; it gave unheard masses the space to speak to each other without limits, across borders, both physical and social. It was supposed to liberate us from gender. But as more and more of our daily lives migrated on line, it seemed it did matter if you were a boy or a girl.’

It’s a tough time to be a woman on the internet. Over the past two generations, the political map of human relations has been redrawn by feminism and by changes in technology. Together they pose questions about the nature and organisation of society that are deeply challenging to those in power, and in both cases, the backlash is on. In this brave new world, old-style sexism is making itself felt in new and frightening ways.

In Cybersexism, Laurie Penny goes to the dark heart of the matter and asks why threats of rape and violence are being used to try to silence female voices, analyses the structure of online misogyny, and makes a case for real freedom of speech – for everyone.

Laurie Penny. Cybersexism: Sex, Gender and Power on the Internet (London: Bloomsbury, 2013). PDF here.

rainer maria rilke – from “requiem for a friend” (1908)

… That’s what you had to come back for: the lament that we omitted. Can you hear me? I would like to fling my voice out like a cloth over the fragments of your death, and keep pulling at it until it is torn to pieces, and all my words would have to walk around shivering, in the tatters of that voice; as if lament were enough.

But now I must accuse: not the man who withdrew you from yourself (I cannot find him; he looks like everyone), but in this one man, I accuse: all men. When somewhere, from deep within me, there arises the vivid sense of having been a child, the purity and essence of that childhood where I once lived: then I don’t want to know it. I want to form an angel from that sense and hurl him upward, into the front row of angels who scream out, reminding God.

For this suffering has lasted far too long; none of us can bear it; it is too heavy — this tangled suffering of spurious love which, building on convention like a habit, calls itself just, and fattens on injustice. Show me a man with a right to his possession. Who can possess what cannot hold its own self, but only, now and then, will blissfully catch itself, then quickly throw itself away, like a child playing with a ball. As little as a captain can hold the carved Nike facing outward from his ship’s prow when the lightness of her godhead suddenly lifts her up, into the bright sea-wind: so little can one of us call back the woman who, now no longer seeing us, walks on along the narrow strip of her existence as though by miracle, in perfect safety — unless, that is, he wishes to do wrong. For this is wrong, if anything is wrong: not to enlarge the freedom of a love with all the inner freedom one can summon. We need, in love, to practice only this: letting each other go. For holding on comes easily; we do not need to learn it.

Are you still here? Are you standing in some corner? You knew so much of all this, you were able to do so much; you passed through life so open to all things, like an early morning. I know: women suffer; for love means being alone; and artists in their work sometimes intuit that they must keep transforming, where they love. You began both; both exist in that which any fame takes from you and disfigures. Oh you were far beyond all fame; were almost invisible; had withdrawn your beauty, softly, as one would lower a brightly colored flag on the gray morning after a holiday. You had just one desire: a year’s long work — which was never finished; was somehow never finished. If you are still here with me, if in this darkness there is still some place where your spirit resonates on the shallow sound waves stirred up by my voice: hear me: help me. We can so easily slip back from what we have struggled to attain, abruptly, into a life we never wanted; can find that we are trapped, as in a dream, and die there, without ever waking up. This can occur. Anyone who has lifted his blood into a years-long work may find that he can’t sustain it, the force of gravity is irresistible, and it falls back, worthless. For somewhere there is an ancient enmity between our daily life and the great work. Help me, in saying it, to understand it.

Do not return. If you can bear to, stay dead with the dead. The dead have their own tasks. But help me, if you can without distraction, since in me what is most distant sometimes helps.

[Translator: Stephen Mitchell]

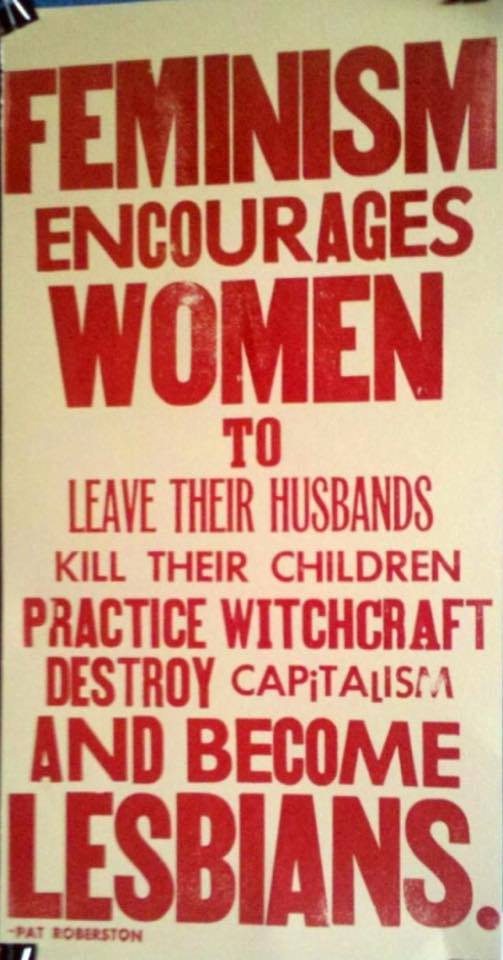

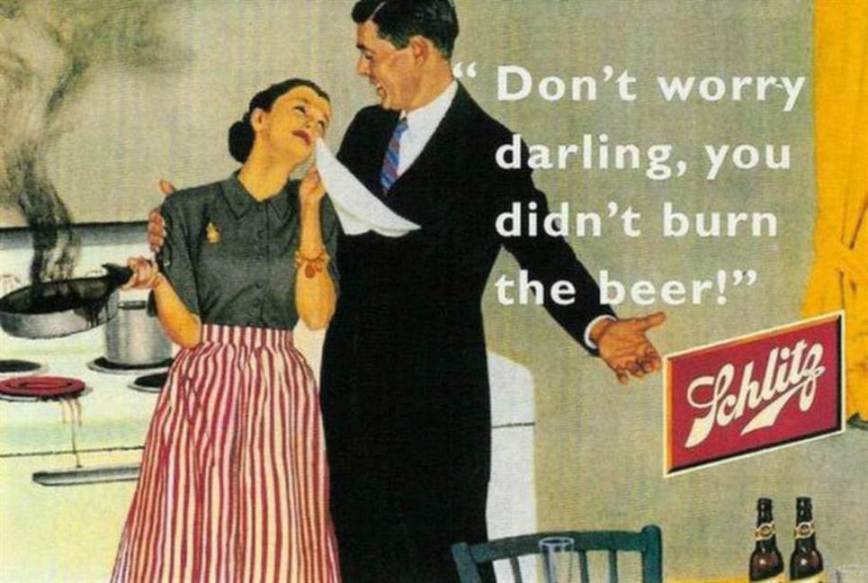

a perennial favourite

john berger – ways of seeing (1972)

I cannot overstate how immensely John Berger contributed to awakening a critical understanding of Western cultural aesthetics and ethics in me. I feel deeply indebted. Here’s a wonderful recent interview with the man.

On this, his 90th birthday, I thought it fitting to look back on this BAFTA award-winning TV series from 1972, which rapidly became regarded as one of the most influential art programmes ever made. Ways of Seeing is a four-part BBC series of 30-minute films, created chiefly by writer John Berger and producer Mike Dibb. Berger’s scripts were adapted into a book of the same name.

The series and book critique traditional Western cultural aesthetics by raising questions about hidden ideologies in visual images. The series is partially a response to Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation series, which represents a more traditionalist view of the Western artistic and cultural canon.

In the first programme, Berger examines the impact of photography on our appreciation of art from the past.

The second programme deals with the portrayal of the female nude, an important part of the tradition of European art. Berger examines these paintings and asks whether they celebrate women as they really are or only as men would like them to be.

With the invention of oil paint around 1400, painters were able to portray people and objects with an unprecedented degree of realism, and painting became the ideal way to celebrate private possessions. In this programme, John Berger questions the value we place on that tradition.

In this programme, Berger analyses the images of advertising and publicity and shows how they relate to the tradition of oil painting – in moods, relationships and poses.

More John Berger on Fleurmach:

John Berger on being born a woman

on the politics and approaches to shutdown

“What might begin as a space whose protest action aims to form humanising culture where Black disabled, trans, queer, and womxn’s bodies are safe and heard, is very quickly appropriated by the anti-blackness of up high – a force that polarises the complexity of oppression and attempts to direct and contain action into the physically violent (inherently colonialist) form that it understands best. In this sense, the state functions to direct the protest politik into the Afropessimistic voice, one that we know disinherits those who do not immediately come to mind when we say the word “black” (ie: black disabled, trans, queer, and womxn’s bodies) and one that abandons the pursuit of humanity, in favour of unhealthy martyrdom and recklessness.

“So apart from the predictability of state-sanctioned physical violence in the form of stun grenades, teargas, rubber bullets, arrest and jail time, it is important to understand this state provocation as incredibly strategic in the way it seeks to awaken retaliation in the same form. It begs us for physical retaliation – the kind that re-confirms black people as bodies, the kind that forces the “you can’t kill us all” mantra – basically the kind of protest that black able-bodied cis-heterosexual men happen to be good at leading and controlling, the kind that does not challenge structural power, but fulfils the fantasy of Fanon’s black man in replacing his white master.”

obnoxious af

ann magnuson performs kate bush’s “wow” (c. 1997)

“In promotion of her fantastic “The Luv Show” CD (and in anticipation of her much later release, “Pretty Songs”), Ann Magnuson wowed the crowds at two live shows at Luna Park. Along with her own songs and a few other covers, she included this Kate Bush gem as one of the “pretty songs”…

Sadly, this was only 1997 or so…so this is recorded on a tape recorder and sounds a bit muddy. No matter. It’s still worth a listen. Enjoy.”

bell hooks – understanding patriarchy (2004)

“The crisis facing men is not the crisis of masculinity, it is the crisis of patriarchal masculinity. Until we make this distinction clear, men will continue to fear that any critique of patriarchy represents a threat.”

Patriarchy is the single most life-threatening social disease assaulting the male body and spirit in our nation. Yet most men do not use the word “patriarchy” in everyday life. Most men never think about patriarchy—what it means, how it is created and sustained. Many men in our nation would not be able to spell the word or pronounce it correctly. The word “patriarchy” just is not a part of their normal everyday thought or speech.

Men who have heard and know the word usually associate it with women’s liberation, with feminism, and therefore dismiss it as irrelevant to their own experiences. I have been standing at podiums talking about patriarchy for more than thirty years. It is a word I use daily, and men who hear me use it often ask me what I mean by it.

Nothing discounts the old antifeminist projection of men as all-powerful more than their basic ignorance of a major facet of the political system that shapes and informs male identity and sense of self from birth until death. I often use the phrase “imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy” to describe the interlocking political systems that are the foundation of our nation’s politics. Of these systems the one that we all learn the most about growing up is the system of patriarchy, even if we never know the word, because patriarchal gender roles are assigned to us as children and we are given continual guidance about the ways we can best fulfill these roles.

Patriarchy is a political-social system that insists that males are inherently dominating, superior to everything and everyone deemed weak, especially females, and endowed with the right to dominate and rule over the weak and to maintain that dominance through various forms of psychological terrorism and violence. When my older brother and I were born with a year separating us in age, patriarchy determined how we would each be regarded by our parents. Both our parents believed in patriarchy; they had been taught patriarchal thinking through religion.

At church they had learned that God created man to rule the world and everything in it and that it was the work of women to help men perform these tasks, to obey, and to always assume a subordinate role in relation to a powerful man. They were taught that God was male. These teachings were reinforced in every institution they encountered– schools, courthouses, clubs, sports arenas, as well as churches. Embracing patriarchal thinking, like everyone else around them, they taught it to their children because it seemed like a “natural” way to organize life.

As their daughter I was taught that it was my role to serve, to be weak, to be free from the burden of thinking, to caretake and nurture others. My brother was taught that it was his role to be served; to provide; to be strong; to think, strategize, and plan; and to refuse to caretake or nurture others. I was taught that it was not proper for a female to be violent, that it was “unnatural.” My brother was taught that his value would be determined by his will to do violence (albeit in appropriate settings). He was taught that for a boy, enjoying violence was a good thing (albeit in appropriate settings). He was taught that a boy should not express feelings. I was taught that girls could and should express feelings, or at least some of them.

When I responded with rage at being denied a toy, I was taught as a girl in a patriarchal household that rage was not an appropriate feminine feeling, that it should not only not be expressed but be eradicated. When my brother responded with rage at being denied a toy, he was taught as a boy in a patriarchal household that his ability to express rage was good but that he had to learn the best setting to unleash his hostility. It was not good for him to use his rage to oppose the wishes of his parents, but later, when he grew up, he was taught that rage was permitted and that allowing rage to provoke him to violence would help him protect home and nation.

We lived in farm country, isolated from other people. Our sense of gender roles was learned from our parents, from the ways we saw them behave. My brother and I remember our confusion about gender. In reality I was stronger and more violent than my brother, which we learned quickly was bad. And he was a gentle, peaceful boy, which we learned was really bad. Although we were often confused, we knew one fact for certain: we could not be and act the way we wanted to, doing what we felt like. It was clear to us that our behavior had to follow a predetermined, gendered script. We both learned the word “patriarchy” in our adult life, when we learned that the script that had determined what we should be, the identities we should make, was based on patriarchal values and beliefs about gender.

I was always more interested in challenging patriarchy than my brother was because it was the system that was always leaving me out of things that I wanted to be part of. In our family life of the fifties, marbles were a boy’s game. My brother had inherited his marbles from men in the family; he had a tin box to keep them in. All sizes and shapes, marvelously colored, they were to my eye the most beautiful objects. We played together with them, often with me aggressively clinging to the marble I liked best, refusing to share. When Dad was at work, our stay-at-home mom was quite content to see us playing marbles together. Yet Dad, looking at our play from a patriarchal perspective, was disturbed by what he saw. His daughter, aggressive and competitive, was a better player than his son. His son was passive; the boy did not really seem to care who won and was willing to give over marbles on demand. Dad decided that this play had to end, that both my brother and I needed to learn a lesson about appropriate gender roles.

One evening my brother was given permission by Dad to bring out the tin of marbles. I announced my desire to play and was told by my brother that “girls did not play with marbles,” that it was a boy’s game. This made no sense to my four- or five-year-old mind, and I insisted on my right to play by picking up marbles and shooting them. Dad intervened to tell me to stop. I did not listen. His voice grew louder and louder. Then suddenly he snatched me up, broke a board from our screen door, and began to beat me with it, telling me, “You’re just a little girl. When I tell you to do something, I mean for you to do it.” He beat me and he beat me, wanting me to acknowledge that I understood what I had done. His rage, his violence captured everyone’s attention. Our family sat spellbound, rapt before the pornography of patriarchal violence.

After this beating I was banished—forced to stay alone in the dark. Mama came into the bedroom to soothe the pain, telling me in her soft southern voice, “I tried to warn you. You need to accept that you are just a little girl and girls can’t do what boys do.” In service to patriarchy her task was to reinforce that Dad had done the right thing by, putting me in my place, by restoring the natural social order.

I remember this traumatic event so well because it was a story told again and again within our family. No one cared that the constant retelling might trigger post-traumatic stress; the retelling was necessary to reinforce both the message and the remembered state of absolute powerlessness. The recollection of this brutal whipping of a little-girl daughter by a big strong man, served as more than just a reminder to me of my gendered place, it was a reminder to everyone watching/remembering, to all my siblings, male and female, and to our grown-woman mother that our patriarchal father was the ruler in our household. We were to remember that if we did not obey his rules, we would be punished, punished even unto death. This is the way we were experientially schooled in the art of patriarchy.

There is nothing unique or even exceptional about this experience. Listen to the voices of wounded grown children raised in patriarchal homes and you will hear different versions with the same underlying theme, the use of violence to reinforce our indoctrination and acceptance of patriarchy. In How Can I Get Through to You? family therapist Terrence Real tells how his sons were initiated into patriarchal thinking even as their parents worked to create a loving home in which antipatriarchal values prevailed. He tells of how his young son Alexander enjoyed dressing as Barbie until boys playing with his older brother witnessed his Barbie persona and let him know by their gaze and their shocked, disapproving silence that his behavior was unacceptable:

Without a shred of malevolence, the stare my son received transmitted a message. You are not to do this. And the medium that message was broadcast in was a potent emotion: shame. At three, Alexander was learning the rules. A ten second wordless transaction was powerful enough to dissuade my son from that instant forward from what had been a favorite activity. I call such moments of induction the “normal traumatization” of boys.

To indoctrinate boys into the rules of patriarchy, we force them to feel pain and to deny their feelings.

My stories took place in the fifties; the stories Real tells are recent. They all underscore the tyranny of patriarchal thinking, the power of patriarchal culture to hold us captive. Real is one of the most enlightened thinkers on the subject of patriarchal masculinity in our nation, and yet he lets readers know that he is not able to keep his boys out of patriarchy’s reach. They suffer its assaults, as do all boys and girls, to a greater or lesser degree. No doubt by creating a loving home that is not patriarchal, Real at least offers his boys a choice: they can choose to be themselves or they can choose conformity with patriarchal roles. Real uses the phrase “psychological patriarchy” to describe the patriarchal thinking common to females and males. Despite the contemporary visionary feminist thinking that makes clear that a patriarchal thinker need not be a male, most folks continue to see men as the problem of patriarchy. This is simply not the case. Women can be as wedded to patriarchal thinking and action as men.

Psychotherapist John Bradshaw’s clear sighted definition of patriarchy in Creating Love is a useful one: “The dictionary defines ‘patriarchy’ as a ‘social organization marked by the supremacy of the father in the clan or family in both domestic and religious functions’.” Patriarchy is characterized by male domination and power. He states further that “patriarchal rules still govern most of the world’s religious, school systems, and family systems.” Describing the most damaging of these rules, Bradshaw lists “blind obedience—the foundation upon which patriarchy stands; the repression of all emotions except fear; the destruction of individual willpower; and the repression of thinking whenever it departs from the authority figure’s way of thinking.” Patriarchal thinking shapes the values of our culture. We are socialized into this system, females as well as males. Most of us learned patriarchal attitudes in our family of origin, and they were usually taught to us by our mothers. These attitudes were reinforced in schools and religious institutions.

The contemporary presence of female-headed households has led many people to assume that children in these households are not learning patriarchal values because no male is present. They assume that men are the sole teachers of patriarchal thinking. Yet many female-headed households endorse and promote patriarchal thinking with far greater passion than two-parent households. Because they do not have an experiential reality to challenge false fantasies of gender roles, women in such households are far more likely to idealize the patriarchal male role and patriarchal men than are women who live with patriarchal men every day. We need to highlight the role women play in perpetuating and sustaining patriarchal culture so that we will recognize patriarchy as a system women and men support equally, even if men receive more rewards from that system. Dismantling and changing patriarchal culture is work that men and women must do together.

Clearly we cannot dismantle a system as long as we engage in collective denial about its impact on our lives. Patriarchy requires male dominance by any means necessary, hence it supports, promotes, and condones sexist violence. We hear the most about sexist violence in public discourses about rape and abuse by domestic partners. But the most common forms of patriarchal violence are those that take place in the home between patriarchal parents and children. The point of such violence is usually to reinforce a dominator model, in which the authority figure is deemed ruler over those without power and given the right to maintain that rule through practices of subjugation, subordination, and submission.

Keeping males and females from telling the truth about what happens to them in families is one way patriarchal culture is maintained. A great majority of individuals enforce an unspoken rule in the culture as a whole that demands we keep the secrets of patriarchy, thereby protecting the rule of the father. This rule of silence is upheld when the culture refuses everyone easy access even to the word “patriarchy.” Most children do not learn what to call this system of institutionalized gender roles, so rarely do we name it in everyday speech. This silence promotes denial. And how can we organize to challenge and change a system that cannot be named?

It is no accident that feminists began to use the word “patriarchy” to replace the more commonly used “male chauvinism” and “sexism.” These courageous voices wanted men and women to become more aware of the way patriarchy affects us all. In popular culture the word itself was hardly used during the heyday of contemporary feminism. Antimale activists were no more eager than their sexist male counterparts to emphasize the system of patriarchy and the way it works. For to do so would have automatically exposed the notion that men were all-powerful and women powerless, that all men were oppressive and women always and only victims. By placing the blame for the perpetuation of sexism solely on men, these women could maintain their own allegiance to patriarchy, their own lust for power. They masked their longing to be dominators by taking on the mantle of victimhood.

Like many visionary radical feminists I challenged the misguided notion, put forward by women who were simply fed up with male exploitation and oppression, that men were “the enemy.” As early as 1984 I included a chapter with the title “Men: Comrades in Struggle” in my book Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center urging advocates of feminist politics to challenge any rhetoric which placed the sole blame for perpetuating patriarchy and male domination onto men:

Separatist ideology encourages women to ignore the negative impact of sexism on male personhood. It stresses polarization between the sexes. According to Joy Justice, separatists believe that there are “two basic perspectives” on the issue of naming the victims of sexism: “There is the perspective that men oppress women. And there is the perspective that people are people, and we are all hurt by rigid sex roles.”…Both perspectives accurately describe our predicament. Men do oppress women. People are hurt by rigid sexist role patterns, These two realities coexist. Male oppression of women cannot be excused by the recognition that there are ways men are hurt by rigid sexist roles. Feminist activists should acknowledge that hurt, and work to change it—it exists. It does not erase or lessen male responsibility for supporting and perpetuating their power under patriarchy to exploit and oppress women in a manner far more grievous than the serious psychological stress and emotional pain caused by male conformity to rigid sexist role patterns.

Throughout this essay I stressed that feminist advocates collude in the pain of men wounded by patriarchy when they falsely represent men as always and only powerful, as always and only gaining privileges from their blind obedience to patriarchy. I emphasized that patriarchal ideology brainwashes men to believe that their domination of women is beneficial when it is not:

Often feminist activists affirm this logic when we should be constantly naming these acts as expressions of perverted power relations, general lack of control of one’s actions, emotional powerlessness, extreme irrationality, and in many cases, outright insanity. Passive male absorption of sexist ideology enables men to falsely interpret this disturbed behavior positively. As long as men are brainwashed to equate violent domination and abuse of women with privilege, they will have no understanding of the damage done to themselves or to others, and no motivation to change.

Patriarchy demands of men that they become and remain emotional cripples. Since it is a system that denies men full access to their freedom of will, it is difficult for any man of any class to rebel against patriarchy, to be disloyal to the patriarchal parent, be that parent female or male.

The man who has been my primary bond for more than twelve years was traumatized by the patriarchal dynamics in his family of origin. When I met him he was in his twenties. While his formative years had been spent in the company of a violent, alcoholic dad, his circumstances changed when he was twelve and he began to live alone with his mother.

In the early years of our relationship he talked openly about his hostility and rage toward his abusing dad. He was not interested in forgiving him or understanding the circumstances that had shaped and influenced his dad’s life, either in his childhood or in his working life as a military man. In the early years of our relationship he was extremely critical of male domination of women and children. Although he did not use the word “patriarchy,” he understood its meaning and he opposed it. His gentle, quiet manner often led folks to ignore him, counting him among the weak and the powerless. By the age of thirty he began to assume a more macho persona, embracing the dominator model that he had once critiqued. Donning the mantle of patriarch, he gained greater respect and visibility. More women were drawn to him. He was noticed more in public spheres. His criticism of male domination ceased. And indeed he begin to mouth patriarchal rhetoric, saying the kind of sexist stuff that would have appalled him in the past.

These changes in his thinking and behavior were triggered by his desire to be accepted and affirmed in a patriarchal workplace and rationalized by his desire to get ahead. His story is not unusual. Boys brutalized and victimized by patriarchy more often than not become patriarchal, embodying the abusive patriarchal masculinity that they once clearly recognized as evil. Few men brutally abused as boys in the name of patriarchal maleness courageously resist the brainwashing and remain true to themselves. Most males conform to patriarchy in one way or another.

Indeed, radical feminist critique of patriarchy has practically been silenced in our culture. It has become a subcultural discourse available only to well-educated elites. Even in those circles, using the word “patriarchy” is regarded as passé. Often in my lectures when I use the phrase “imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy” to describe our nation’s political system, audiences laugh. No one has ever explained why accurately naming this system is funny. The laughter is itself a weapon of patriarchal terrorism. It functions as a disclaimer, discounting the significance of what is being named. It suggests that the words themselves are problematic and not the system they describe. I interpret this laughter as the audience’s way of showing discomfort with being asked to ally themselves with an anti-patriarchal disobedient critique. This laughter reminds me that if I dare to challenge patriarchy openly, I risk not being taken seriously.

Citizens in this nation fear challenging patriarchy even as they lack overt awareness that they are fearful, so deeply embedded in our collective unconscious are the rules of patriarchy. I often tell audiences that if we were to go door-to-door asking if we should end male violence against women, most people would give their unequivocal support. Then if you told them we can only stop male violence against women by ending male domination, by eradicating patriarchy, they would begin to hesitate, to change their position. Despite the many gains of contemporary feminist movement—greater equality for women in the workforce, more tolerance for the relinquishing of rigid gender roles—patriarchy as a system remains intact, and many people continue to believe that it is needed if humans are to survive as a species. This belief seems ironic, given that patriarchal methods of organizing nations, especially the insistence on violence as a means of social control, has actually led to the slaughter of millions of people on the planet.

Until we can collectively acknowledge the damage patriarchy causes and the suffering it creates, we cannot address male pain. We cannot demand for men the right to be whole, to be givers and sustainers of life. Obviously some patriarchal men are reliable and even benevolent caretakers and providers, but still they are imprisoned by a system that undermines their mental health.

Patriarchy promotes insanity. It is at the root of the psychological ills troubling men in our nation. Nevertheless there is no mass concern for the plight of men. In Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man, Susan Faludi includes very little discussion of patriarchy:

Ask feminists to diagnose men’s problems and you will often get a very clear explanation: men are in crisis because women are properly challenging male dominance. Women are asking men to share the public reins and men can’t bear it. Ask antifeminists and you will get a diagnosis that is, in one respect, similar. Men are troubled, many conservative pundits say, because women have gone far beyond their demands for equal treatment and are now trying to take power and control away from men…The underlying message: men cannot be men, only eunuchs, if they are not in control. Both the feminist and antifeminist views are rooted in a peculiarly modern American perception that to be a man means to be at the controls and at all times to feel yourself in control.

Faludi never interrogates the notion of control. She never considers that the notion that men were somehow in control, in power, and satisfied with their lives before contemporary feminist movement is false.

Patriarchy as a system has denied males access to full emotional well-being, which is not the same as feeling rewarded, successful, or powerful because of one’s capacity to assert control over others. To truly address male pain and male crisis we must as a nation be willing to expose the harsh reality that patriarchy has damaged men in the past and continues to damage them in the present. If patriarchy were truly rewarding to men, the violence and addiction in family life that is so all-pervasive would not exist. This violence was not created by feminism. If patriarchy were rewarding, the overwhelming dissatisfaction most men feel in their work lives—a dissatisfaction extensively documented in the work of Studs Terkel and echoed in Faludi’s treatise—would not exist.

In many ways Stiffed was yet another betrayal of American men because Faludi spends so much time trying not to challenge patriarchy that she fails to highlight the necessity of ending patriarchy if we are to liberate men. Rather she writes:

Instead of wondering why men resist women’s struggle for a freer and healthier life, I began to wonder why men refrain from engaging in their own struggle. Why, despite a crescendo of random tantrums, have they offered no methodical, reasoned response to their predicament: Given the untenable and insulting nature of the demands placed on men to prove themselves in our culture, why don’t men revolt?…Why haven’t men responded to the series of betrayals in their own lives—to the failures of their fathers to make good on their promises–with something coequal to feminism?

Note that Faludi does not dare risk either the ire of feminist females by suggesting that men can find salvation in feminist movement or rejection by potential male readers who are solidly antifeminist by suggesting that they have something to gain from engaging feminism. So far in our nation visionary feminist movement is the only struggle for justice that emphasizes the need to end patriarchy. No mass body of women has challenged patriarchy and neither has any group of men come together to lead the struggle. The crisis facing men is not the crisis of masculinity, it is the crisis of patriarchal masculinity. Until we make this distinction clear, men will continue to fear that any critique of patriarchy represents a threat. Distinguishing political patriarchy, which he sees as largely committed to ending sexism, therapist Terrence Real makes clear that the patriarchy damaging us all is embedded in our psyches: Psychological patriarchy is the dynamic between those qualities deemed “masculine” and “feminine” in which half of our human traits are exalted while the other half is devalued. Both men and women participate in this tortured value system.

Psychological patriarchy is a “dance of contempt,” a perverse form of connection that replaces true intimacy with complex, covert layers of dominance and submission, collusion and manipulation. It is the unacknowledged paradigm of relationships that has suffused Western civilization generation after generation, deforming both sexes, and destroying the passionate bond between them.

By highlighting psychological patriarchy, we see that everyone is implicated and we are freed from the misperception that men are the enemy. To end patriarchy we must challenge both its psychological and its concrete manifestations in daily life. There are folks who are able to critique patriarchy but unable to act in an antipatriarchal manner.

To end male pain, to respond effectively to male crisis, we have to name the problem. We have to both acknowledge that the problem is patriarchy and work to end patriarchy. Terrence Real offers this valuable insight:

“The reclamation of wholeness is a process even more fraught for men than it has been for women, more difficult and more profoundly threatening to the culture at large.”

If men are to reclaim the essential goodness of male being, if they are to regain the space of openheartedness and emotional expressiveness that is the foundation of well-being, we must envision alternatives to patriarchal masculinity. We must all change.

___

This is an excerpt from The Will To Change by bell hooks (chapter 2).

bell hooks is an American social activist, feminist and author. She was born on September 25, 1952. bell hooks is the nom de plume for Gloria Jean Watkins. bell hooks examines the multiple networks that connect gender, race, and class. She examines systematic oppression with the goal of a liberatory politics. She also writes on the topics of mass media, art, and history. bell hooks is a prolific writer, having composed a plethora of articles for mainstream and scholarly publications. bell hooks has written and published dozens of books. At Yale University, bell hooks was a Professor of African and African-American Studies and English. At Oberlin College, she was an Associate Professor of Women‚’s Studies and American Literature. At the City College of New York, bell hooks also held the position of Distinguished Lecturer of English Literature. bell hooks has been awarded The American Book Awards/Before Columbus Foundation Award, The Writer’s Award from Lila Wallace-Reader’s Digest Fund, and The Bank Street College Children’s Book of the Year. She has also been ranked as one of the most influential American thinkers by Publisher’s Weekly and The Atlantic monthly.

This work is licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

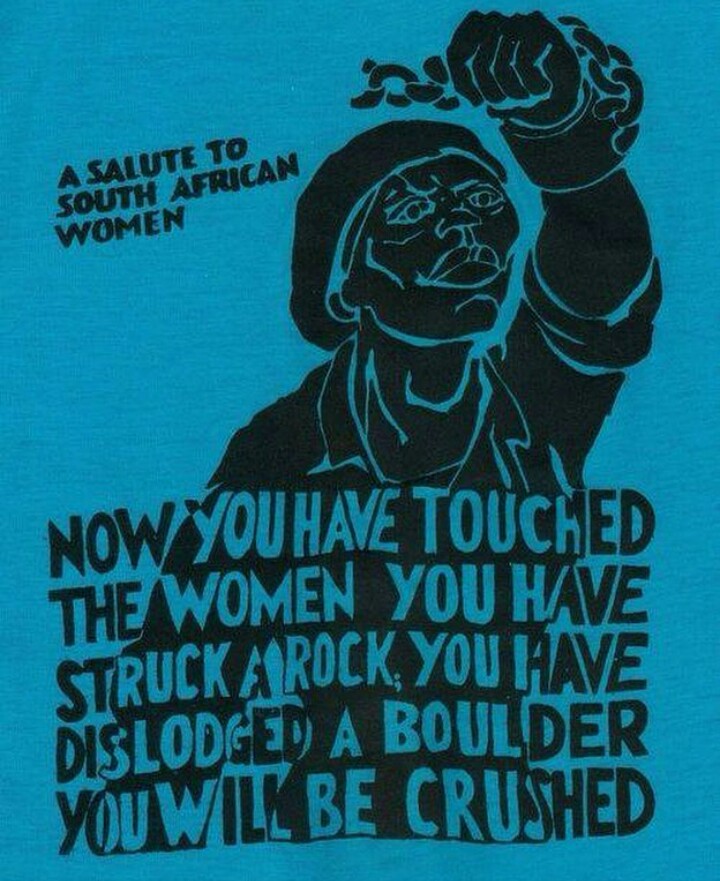

9 august

dora maar/man ray – the years lie in wait for you (1936)

Excerpt from an article by Aya Lurie, from the exhibition catalogue: “The Naked Eye – Surrealist Photography in the First Half of the 20th Century”, 2013:

The languishing face of a strikingly beautiful young woman is seen behind a spider web. Is she trapped behind the web? Is she trapped in it? The spider may be lying in wait for her, and maybe she is on the prowl, with her manicured feminine hands, which call to mind the articulated legs of a spider. Perhaps it is rather the lurking time, as indicated by the title of the photograph, that threatens youth and beauty, serving as a reminder of their ephemerality.

The association between the woman and the spider dates back to Greek mythology, where it is embodied in the figure of Arachne, a weaver who made Athena jealous enough to turn her into a spider.1

In the history of culture, the figure of the “spider-woman” has come to be identified with the femme fatale — the archetype of the woman who leads to the downfall of the man attracted to her. In this context, Arachne is presented as a patient plotter who spins a web of schemes to trap and devour the reckless male.2 Dr. Ruth Markus, in her essay about the representations of the castrating woman in Surrealist art, ties the female praying mantis with the female “Black Widow” spider, which characteristically devour their males during or directly after the sexual act. She explains the Surrealist interest in the mantis and similar insects in that they represent the two primordial Freudian instincts: Eros and Thanatos.3

Dora Maar linked the photographed portrait by Man Ray with a manipulated image of a cobweb, to create the effect of transparent contours on the woman’s face in the final print. The resulting photomontage thus fuses the woman’s figure with the spider and its web. The Surrealists were drawn to the mimetic ability of various animals to camouflage themselves in nature, and created many works in which flora, fauna, and the inanimate merge and assimilate into one another.4 In the spirit of pantheist romanticism, this capacity was taken to represent an aspiration to eliminate the boundaries between man and nature, to the point of total fusion with the cosmos, which leads to absolute void. It is, in fact, a yearning for a primordial unconscious state, an existential state which precedes consciousness.

In the photograph in question, the paths of two of the most fascinating women who operated among the Surrealists cross. Photographer Dora Maar (born as Henrietta Theodora Markovitch) was a talented artist in her own right, but her fame came mainly from her relationship with Pablo Picasso, her partner, who often depicted her figure. In addition, Maar also modeled for Man Ray in some of his prime photographs…

… The model in Maar’s photograph is Nusch Éluard (1906–1946, née Maria Benz), a German show dancer who, in 1934, married poet Paul Éluard, one of the kingpins of Surrealism, after his first wife, Gala, left him for Salvador Dalí… Nusch Éluard also served as inspiration for her husband’s poetic work, and he combined her photographs in his books of poetry as elaboration and illustration for the written text.

In 1935, daring nude photographs of Nusch were included in his book Facile. Following her sudden death in 1946, at the age of 40, her portrait, taken by Dora Maar (with which she constructed the montage here), was included in a book by her husband in her memory, Le temps débordé (Time Overflows). The portrait, this time without cobweb,[fig. 3] accompanied the poem “Ecstasy” in which Éluard praises and mourns his wife: “I am in front of this feminine land / Like a child in front of the fire / Smiling vaguely with tears in my eyes / […] / I am in front of this feminine land / Like a branch in the fire.”5

- See Ovid’s Metamorphoses, books 6–10, ed. William S. Anderson (Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1972), pp. 15-22.

- See Doron Lurie, cat. Femme Fatale (Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 2006), p. 108 [Hebrew].

- Ruth Markus, “Surrealism’s Praying Mantis and Castrating Woman”, Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 21:1 (Spring/Summer, 2000), pp. 33-39.

- Ibid.

- Paul Éluard, “Ecstasy,” trans. A. S. Kline, 2001. http://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/French/Eluard.htm.

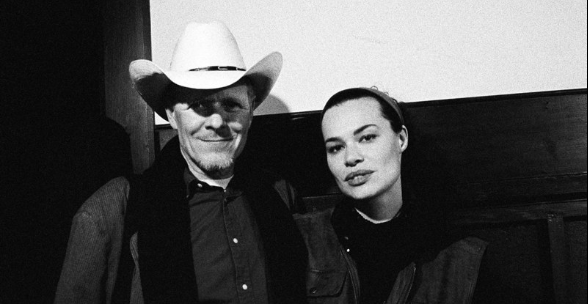

grimm versus gira (2008 – 2016)

I share this in solidarity with Larkin Grimm, and my niece Juliette, and every other woman who has been exploited or violated through unequal power relationships during artistic collaboration. Speak your truth. Don’t shut up. Make them squirm. Let them burn.

—

Yesterday, singer/songwriter Larkin Grimm claimed that Swans frontman Michael Gira raped her in spring 2008, when she was recording her album Parplar for Gira’s Young God label. In a Facebook post yesterday, she said she confronted Gira and he then dropped her from his label. Gira called Grimm’s accusations “a slanderous lie” on his personal Facebook page. In an official statement through his publicist, Gira has acknowledged the spring 2008 night in question, but calls the incident “an awkward mistake.” Read his full statement below. Update (2/27, 9:40 a.m.): Grimm sent us a statement in response to Gira’s comments, which she calls “an admission of guilt.” Read it below.

Michael Gira:

Eight years ago, while I was still married to my first wife, Larkin Grimm and I headed towards a consensual romantic moment that fortunately was not consummated. As she wrote in her recent social media postings about that night, I said to her, “this doesn’t feel right,” and abruptly but completely our only intimate encounter ended. It was an awkward mistake.

Larkin may regret, as I certainly do, that the ill-advised tryst went even that far, but now, as then, I hold her in high esteem for her music and her courage as an artist.

I long ago apologized to my wife and family and told them the truth about this incident. My hope is that Larkin finds peace with the demons that have been darkening her soul since long before she and I ever met.

Larkin Grimm:

This is a perfect example of why we need to have education about consent. In a gentlemanly move he admits the act happened but cannot conceive of himself as a rapist. Thank you Michael Gira for your honesty. This is your truth as you remember it. Unfortunately, this was still rape. I said no to you many times before that day, begged you not to interfere with me sexually, even made it a part of a verbal agreement we had when I signed a contract with you. I asked you to promise that you would never have sex with me. You assured me that I could trust you. That is about as clear a NO as I could ever cry. I asked for this because I had had other experiences in my music career and I KNEW.

That night I was far too intoxicated to give you consent for any sexual act. The psychological effects of this betrayal were devastating. Even worse, when I finally confronted you about what you had done, you terminated my relationship with Young God Records, damaging my career and leading people to believe there was something wrong with me or my music.

In the end, this is about business. Art is my career. I have worked long and hard for this career, making incredible sacrifices along the way to continue to make music. The fact that a man in power can throw a woman’s life and work away like they are garbage, simply because she won’t sleep with him, is an immoral injustice that happens to many, many women in music. I won’t stand for it and neither should you.

The “Demons darkening my soul” are the men like you who interfere with my ability to do my work as a musician. This is a job I am good at. All I want is to be left in peace while I am working.

From Pitchfork.

robert greene – the 48 laws of power, or, how to be a consummately oppressive douchebag

Illustration by William Steig from Wilhelm Reich’s “Listen, Little Man” (1945)

LAW 1

NEVER OUTSHINE THE MASTER

Always make those above you feel comfortably superior. In your desire to please or impress them, do not go too far in displaying your talents or you might accomplish the opposite-inspire fear and insecurity. Make your masters appear more brilliant than they are and you will attain the heights of power.

LAW 2

NEVER PUT TOO MUCH TRUST IN FRIENDS, LEARN HOW TO USE ENEMIES

Be wary of friends-they will betray you more quickly, for they are easily aroused to envy. They also become spoiled and tyrannical. But hire a former enemy and he will be more loyal than a friend, because he has more to prove. In fact, you have more to fear from friends than from enemies. If you have no enemies, find a way to make them.

LAW 3

CONCEAL YOUR INTENTIONS

Keep people off-balance and in the dark, by never revealing the purpose behind your actions. If they have no clue what you are up to, they cannot prepare a defense. Guide them far enough down the wrong path, envelop them in enough smoke, and by the time they realize your intentions, it will be too late.

LAW 4

ALWAYS SAY LESS THAN NECESSARY

When you are trying to impress people with words, the more you say, the more common you appear, and the less in control. Even if you are saying something banal, it will seem original if you make it vague, open-ended, and sphinxlike. Powerful people impress and intimidate by saying less. The more you say, the more likely you are to say something foolish.

LAW 5

SO MUCH DEPENDS ON REPUTATION- GUARD IT WITH YOUR LIFE

Reputation is the cornerstone of power. Through reputation alone you can intimidate and win; once it slips, however, you are vulnerable, and will be attacked on all sides. Make your reputation unassailable. Always be alert to potential attacks and thwart them before they happen. Meanwhile, learn to destroy your enemies by opening holes in their own reputations. Then stand aside and let public opinion hang them.

LAW 6

COURT ATTENTION AT ALL COST

Everything is judged by its appearance; what is unseen counts for nothing. Never let yourself get lost in the crowd, then, or buried in oblivion. Stand out. Be conspicuous, at all cost. Make yourself a magnet of attention by appearing larger, more colorful, more mysterious than the bland and timid masses.

LAW 7

GET OTHERS TO DO THE WORK FOR YOU, BUT ALWAYS TAKE THE CREDIT

Use the wisdom, knowledge, and legwork of other people to further your own cause. Not only will such assistance save you valuable time and energy, it will give you a godlike aura of efficiency and speed. In the end your helpers will be forgotten and you will be remembered. Never do yourself what others can do for you.

LAW 8

MAKE OTHER PEOPLE COME TO YOU-USE BAIT IF NECESSARY

When you force the other person to act, you are the one in control. It is always better to make your opponent come to you, abandoning his own plans in the process. Lure him with fabulous gains-then attack. You hold the cards.

LAW 9

WIN THROUGH YOUR ACTIONS, NEVER THROUGH ARGUMENT

Any momentary triumph you think you have gained through argument is really a Pyrrhic victory: The resentment and ill will you stir up is stronger and lasts longer than any momentary change of opinion. It is much more powerful to get others to agree with you through your actions, without saying a word. Demonstrate, do not explicate.

LAW 10

INFECTION: AVOID THE UNHAPPY AND UNLUCKY

You can die from someone else’s misery-emotional states are as infectious as diseases. You may feel you are helping the drowning man but you are only precipitating your own disaster. The unfortunate sometimes draw misfortune on themselves; they will also draw it on you. Associate with the happy and fortunate instead.

LAW 11

LEARN TO KEEP PEOPLE DEPENDENT ON YOU

To maintain your independence you must always be needed and wanted. The more you are relied on, the more freedom you have. Make people depend on you for their happiness and prosperity and you have nothing to fear. Never teach them enough so that they can do without you.

LAW 12

USE SELECTIVE HONESTY AND GENEROSITY TO DISARM YOUR VICTIM

One sincere and honest move will cover over dozens of dishonest ones. Open-hearted gestures of honesty and generosity bring down the guard of even the most suspicious people. Once your selective honesty opens a hole in their armor, you can deceive and manipulate them at will. A timely gift-a Trojan horse-will serve the same purpose.

LAW 13

WHEN ASKING FOR HELP, APPEAL TO PEOPLE’S SELF-INTEREST, NEVER TO THEIR MERCY OR GRATITUDE

If you need to tum to an ally for help, do not bother to remind him of your past assistance and good deeds. He will find a way to ignore you. Instead, uncover something in your request, or in your alliance with him, that will benefit him, and emphasize it out of all proportion. He will respond enthusiastically when he sees some thing to be gained for himself.

From Wilhelm Reich’s “Listen, Little Man” (1945)

LAW 14

POSE AS A FRIEND, WORK AS A SPY

Knowing about your rival is critical. Use spies to gather valuable information that will keep you a step ahead. Better still: Play the spy yourself. In polite social encounters, learn to probe. Ask indirect questions to get people to reveal their weaknesses and intentions. There is no occasion that is not an opportunity for artful spying.

LAW 15

CRUSH YOUR ENEMY TOTALLY

All great leaders since Moses have known that a feared enemy must be crushed completely. (Sometimes they have learned this the hard way.) If one ember is left alight, no matter how dimly it smolders, afire will eventually break out. More is lost through stopping halfway than through total annihilation: The enemy will recover, and will seek revenge. Crush him, not only in body but in spirit.

LAW 16

USE ABSENCE TO INCREASE RESPECT AND HONOR

Too much circulation makes the price go down: The more you are seen and heard from, the more common you appear. If you are already established in a group, temporary withdrawal from it will make you more talked about, even more admired. You must learn when to leave. Create value through scarcity.

LAW 17

KEEP OTHERS IN SUSPENDED TERROR: CULTIVATE AN AIR OF UNPREDICTABILITY

Humans are creatures of habit with an insatiable need to see familiarity in other people’s actions. Your predictability gives them a sense of control. Tum the tables: Be deliberately unpredictable. Behavior that seems to have no consistency or purpose will keep them off-balance, and they will wear themselves out trying to explain your moves. Taken to an extreme, this strategy can intimidate and terrorize.

LAW 18

DO NOT BUILD FORTRESSES TO PROTECT YOURSELF- ISOLATION IS DANGEROUS

The world is dangerous and enemies are everywhere-everyone has to protect themselves. A fortress seems the safest. But isolation exposes you to more dangers than it protects you from- it cuts you off from valuable information, it makes you conspicuous and an easy target. Better to circulate among people, find allies, mingle. You are shielded from your enemies by the crowd.

LAW 19

KNOW WHO YOU’RE DEALING WITH: DO NOT OFFEND THE WRONG PERSON

There are many different kinds of people in the world, and you can never assume that everyone will react to your strategies in the same way. Deceive or outmaneuver some people and they will spend the rest of their lives seeking revenge. They are wolves in lambs’ clothing. Choose your victims and opponents carefully, then never offend or deceive the wrong person.

LAW 20

DO NOT COMMIT TO ANYONE

It is the fool who always rushes to take sides. Do not commit to any side or cause but yourself. By maintaining your independence, you become the master of others-playing people against one another, making them pursue you.

LAW 21

PLAY A SUCKER TO CATCH A SUCKER: SEEM DUMBER THAN YOUR MARK

No one likes feeling stupider than the next person. The trick, then, is to make your victims feel smart-and not just smart, but smarter than you are. Once convinced of this, they will never suspect that you may have ulterior motives.

LAW 22

USE THE SURRENDER TACTIC: TRANSFORM WEAKNESS INTO POWER

When you are weaker, never fight for honor’s sake; choose surrender instead. Surrender gives you time to re cover, time to torment and irritate your conqueror, time to wait for his power to wane. Do not give him the satisfaction of fighting and defeating you- surrender first. By turning the other cheek you infuriate and unsettle him. Make surrender a tool of power.

LAW 23

CONCENTRATE YOUR FORCES

Conserve your forces and energies by keeping them concentrated at their strongest point. You gain more by finding a rich mine and mining it deeper, than by flitting from one shallow mine to another-intensity defeats extensity every time. When looking for sources of power to elevate you, find the one key patron, the fat cow who will give you milk for a long time to come.

LAW 24

PLAY THE PERFECT COURTIER

The perfect courtier thrives in a world where everything revolves around power and political dexterity. He has mastered the art of indirection; he flatters, yields to superiors, and asserts power over others in the most oblique and graceful manner. Learn and apply the laws of courtiership and there will be no limit to how far you can rise in the court.

LAW 25

RE-CREATE YOURSELF

Do not accept the rol.es that society foists on you. Re-create yourself by forging a new identity, one that commands attention and never bores the audience. Be the master of your own image rather than letting others define it for you. Incorporate dramatic devices into your public gestures and actions-your power will be enhanced and your character will seem larger than life.

LAW 26

KEEP YOUR HANDS CLEAN

You must seem a paragon of civility and efficiency: Your hands are never soiled by mistakes and nasty deeds. Maintain such a spotless appearance by using others as scapegoats and cat’s-paws to disguise your involvement.

From Wilhelm Reich’s “Listen, Little Man” (1945)

LAW 27

PLAY ON PEOPLE’S NEED TO BELIEVE TO CREATE A CULTLIKE FOLLOWING

People have an overwhelming desire to believe in something. Become the focal point of such desire by offering them a cause, a new faith to follow. Keep your words vague but full of promise; emphasize enthusiasm over rationality and clear thinking. Give your new disciples rituals to perform, ask them to make sacrifices on your behalf. In the absence of organized religion and grand causes, your new belief system will bring you untold power.

LAW 28

ENTER ACTION WITH BOLDNESS

If you are unsure of a course of action, do not attempt it. Your doubts and hesitations will infect your execution. Timidity is dangerous: Better to enter with boldness. Any mistakes you commit through audacity are easily corrected with more audacity. Everyone admires the bold; no one honors the timid.

LAW 29

PLAN ALL THE WAY TO THE END

The ending is everything. Plan all the way to it, taking into account all the possible consequences, obstacles, and twists of fortune that might reverse your hard work and give the glory to others. By planning to the end you will not be overwhelmed by circumstances and you will know when to stop. Gently guide fortune and help determine the future by thinking far ahead.

LAW 30

MAKE YOUR ACCOMPLISHMENTS SEEM EFFORTLESS

Your actions must seem natural and executed with ease. All the toil and practice that go into them, and also all the clever tricks, must be concealed. When you act, act effortlessly, as if you could do much more. Avoid the temptation of revealing how hard you work-it only raises questions. Teach no one your tricks or they will be used against you.

LAW 31

CONTROL THE OPTIONS: GET OTHERS TO PLAY WITH THE CARDS YOU DEAL

The best deceptions are the ones that seem to give the other person a choice: Your victims feel they are in control, but are actually your puppets. Give people options that come out in your favor whichever one they choose. Force them to make choices between the lesser of two evils, both of which serve your purpose. Put them on the horns of a dilemma: They are gored wherever they turn.

LAW 32

PLAY TO PEOPLE’S FANTASIES

The truth is often avoided because it is ugly and unpleasant. Never appeal to truth and reality unless you are prepared for the anger that comes from disenchantment. Life is so harsh and distressing that people who can manufacture romance or conjure up fantasy are like oases in the desert: Everyone flocks to them. There is great power in tapping into the fantasies of the masses.

LAW 33

DISCOVER EACH MAN’S THUMBSCREW

Everyone has a weakness, a gap in the castle wall. That weakness is usually an insecurity, an uncontrollable emotion or need; it can also be a small secret pleasure. Either way, once found, it is a thumbscrew you can tum to your advantage.

LAW 34

BE ROYAL IN YOUR OWN FASHION: ACT LIKE A KING TO BE TREATED LIKE ONE

The way you carry yourself will often determine how you are treated: In the long run, appearing vulgar or common will make people disrespect you. For a king respects himself and inspires the same sentiment in others. By acting regally and confident of your powers, you make yourself seem destined to wear a crown.

LAW 35

MASTER THE ART OF TIMING

Never seem to be in a hurry-hurrying betrays a lack of control over yourself, and over time. Always seem patient, as if you know that everything will come to you eventually. Become a detective of the right moment; sniff out the spirit of the times, the trends that will carry you to power. Learn to stand back when the time is not yet ripe, and to strike fiercely when it has reached fruition.

LAW 36

DISDAIN THINGS YOU CANNOT HAVE: IGNORING THEM IS THE BEST REVENGE

By acknowledging a petty problem you give it existence and credibility. The more attention you pay an enemy, the stronger you make him; and a small mistake is often made worse and more visible when you try to fix it. It is sometimes best to leave things alone. If there is something you want but cannot have, show contempt for it. The less interest you reveal, the more superior you seem.

LAW 37

CREATE COMPELLING SPECTACLES

Striking imagery and grand symbolic gestures create the aura of power-everyone responds to them. Stage spectacles for those around you, then, full of arresting visuals and radiant symbols that heighten your presence. Dazzled by appearances, no one will notice what you are really doing.

From Wilhelm Reich’s “Listen, Little Man” (1945)

LAW 38

THINK AS YOU LIKE BUT BEHAVE LIKE OTHERS

If you make a show of going against the times, flaunting your unconventional ideas and unorthodox ways, people will think that you only want attention and that you look down upon them. They will find a way to punish you for making them feel inferior. It is far safer to blend in and nurture the common touch. Share your originality only with tolerant friends and those who are sure to appreciate your uniqueness.

LAW 39

STIR UP WATERS TO CATCH FISH

Anger and emotion are strategically counterproductive. You must always stay calm and objective. But if you can make your enemies angry while staying calm yourself, you gain a decided advantage. Put your enemies off-balance: Find the chink in their vanity through which you can rattle them and you hold the strings.

LAW 40

DESPISE THE FREE LUNCH

‘What is offered for free is dangerous-it usually involves either a trick or a hidden obligation. ‘What has worth is worth paying for. By paying your own way you stay clear of gratitude, guilt, and deceit. It is also often wise to pay the full price–there is no cutting corners with excellence. Be lavish with your money and keep it circulating, for generosity is a sign and a magnet for power.

LAW 41

AVOID STEPPING INTO A GREAT MAN’S SHOES

What happens first always appears better and more original than what comes after. If you succeed a great man or have a famous parent, you will have to accomplish double their achievements to outshine them. Do not get lost in their shadow, or stuck in a past not of your own making: Establish your own name and identity by changing course. Slay the overbearing father, disparage his legacy, and gain power by shining in your own way.

LAW 42

STRIKE THE SHEPHERD AND THE SHEEP WILL SCATTER

Trouble can often be traced to a single strong individual-the stirrer, the arrogant underling, the poisoner of goodwill. If you allow such people room to operate, others will succumb to their influence. Do not wait for the troubles they cause to multiply, do not try to negotiate with them-they are irredeemable. Neutralize their influence by isolating or banishing them. Strike at the source of the trouble and the sheep will scatter.

LAW 43

WORK ON THE HEARTS AND MINDS OF OTHERS

Coercion creates a reaction that will eventually work against you. You must seduce others into wanting to move in your direction. A person you have seduced becomes your loyal pawn. And the way to seduce others is to operate on their individual psychologies and weaknesses. Soften up the resistant by working on their emotions, playing on what they hold dear and what they fear. Ignore the hearts and minds of others and they will grow to hate you.

LAW 44

DISARM AND INFURIATE WITH THE MIRROR EFFECT

The mirror reflects reality, but it is also the perfect tool for deception: when you mirror your enemies, doing exactly as they do, they cannot figure out your strategy. The Mirror Effect mocks and humiliates them, making them overreact. By holding up a mirror to their psyches, you seduce them with the illusion that you share their values; by holding up a mirror to their actions, you teach them a lesson. Few can resist the power of the Mirror Effect.

LAW 45

PREACH THE NEED FOR CHANGE, BUT NEVER REFORM TOO MUCH AT ONCE

Everyone understands the need for change in the abstract, but on the day-to-day level people are creatures of habit. Too much innovation is traumatic, and will lead to revolt. If you are new to a position of power, or an outsider trying to build a power base, make a show of respecting the old way of doing things. If change is necessary, make it feel like a gentle improvement on the past.

From Wilhelm Reich’s “Listen, Little Man” (1945)

LAW 46

NEVER APPEAR TOO PERFECT

Appearing better than others is always dangerous, but most dangerous of all is to appear to have no faults or weaknesses. Envy creates silent enemies. It is smart to occasionally display defects, and admit to harmless vices, in order to deflect envy and appear more human and approachable. Only gods and the dead can seem perfect with impunity.

LAW 47

DO NOT GO PAST THE MARK YOU AIMED FOR: IN VICTORY, LEARN WHEN TO STOP

The moment of victory is often the moment of greatest peril. In the heat of victory, arrogance and overconfidence can push you past the goal you had aimed for, and by going too far, you make more enemies than you defeat. Do not allow success to go to your head. There is no substitute for strategy and careful planning. Set a goal, and when you reach it, stop.

LAW 48

ASSUME FORMLESSNESS

By taking a shape, by having a visible plan, you open yourself to attack. Instead of taking a form for your enemy to grasp, keep yourself adaptable and on the move. Accept the fact that nothing is certain and no law is fixed. The best way to protect yourself is to be as fluid and formless as water; never bet on stability or lasting order. Everything changes.

wilhelm reich on the plague-ridden vs. the living (1945)

Society moulds human character and in turn human character reproduces social ideology en masse. Thus, in reproducing the negation of life inherent in social ideology, people reproduce their own suppression.

Those who are truly alive are kindly and unsuspecting in their human relationships and consequently endangered under present conditions. They assume that others think and act generously, kindly, and helpfully, in accordance with the laws of life. This natural attitude, fundamental to healthy children as well as to primitive man, inevitably represents a great danger in the struggle for a rational way of life as long as the emotional plague subsists, because the plague-ridden impute their own manner of thinking and acting to their fellow men.

A kindly man believes that all men are kindly, while one infected with the plague believes that all men lie and cheat and are hungry for power. In such a situation the living are at an obvious disadvantage. When they give to the plague-ridden, they are sucked dry, then ridiculed or betrayed.

Read the whole of Reich’s essay, “The Emotional Plague” HERE, and an “orgonomic” analysis of mass murders and their relationship to repression HERE (an interesting take in the light of the Orlando nightclub shooting this past weekend, although I completely disagree with the conclusions drawn by the author about what the USA should do about it! I think, frankly, that the USA has an enormous log in its own eye where repression is concerned.)

Diagram by Wilhelm Reich depicting his theory of the antithetical functional unity between instinct and defense, and illustrating specific impulses.

[EDIT, 14 June 2016]: From Facebook this morning:

charity hamilton – troubled bodies: metaxu, suffering and the encounter with the divine

The body is the canvas on which the female experience is painted and through which female identity is often understood. The female body is a slate on which a patriarchal story has been written, scarred onto the flesh.

For Simone Weil metaxu was simultaneously that which separated and connected, so for instance the wall between two prison cells cuts off the prisoners but was also the means by which they communicated by knocking on that wall. Could the body be that metaxu all at once separating us and connecting us to the Divine? The nature of metaxu is that it offers a route not just for the individual soul but for the souls of others to travel…

—

It’s all well and good to dust off a dead French Jewish Catholic not-quite-feminist-philosopher called Simone Weil and say ‘thanks, your theory of metaxu is great’, but what I want to know within the bones of my so-called soul is how this notion of metaxu can draw me into God, how can it liberate my sisters and how can it usher in the kingdom of the mother of all creation?

Human beings are created in the image of God and formed from the dust of the earth, and thus the body has an echoing significance throughout Christian history. The body is the perceived seat of what some describe as the fall, the locus of the incarnation, the home of crucifixion, the vessel of redemption, salvation and resurrection. The body is not an external meaningless diversion from the spiritual path; rather it is an incredibly important recurring theme both biblically and in Christian tradition and history. Bray and Colebrook state that,

The body is a negotiation with images, but it is also a negotiation with pleasures, pains, other bodies, space, visibility, and medical practice; no single event in this field can act as a general ground for determining the status of the body (Bray and Colebrook, 1998).

Yet more than all of this, the body is the place in which we dwell, it is all we have. As Elizabeth Moltmann Wendell says ‘I am my body’ (Moltmann-Wendell, 1994). For each of our sisters the body is the canvas on which the female experience is painted and through which female identity is often understood. It is on the stage of our female bodies that some of the most fixed church doctrines have been written and enacted. The female body is a slate on which a patriarchal story has been written, scarred onto the flesh. These bodies of ours are patriarchal constructs which must be liberated and re-adopted into the Christian story without the limitations of perceived notions or definitions of ‘gender’.

Isherwood and Stuart assert that ‘From the moment we are asked to believe that Eve was a rib removed from the side of Adam we understand that theology is based in the body and we are at a disadvantage!’ (Isherwood and Stuart, 1998: 15). The historical dichotomy between the Eve and the Mary constructions has led to a definitive inequality for women, both in terms of physical wellbeing and in terms of spiritual and psychological wellbeing. The choices for a woman to be the sin-formed, temptress Eve or the virginal pure vessel Mary are seen historically in the precarious place of women in the church and in society.

Elizabeth Stuart writes that ‘Women were regarded as being ensnared in their bodiliness to a far greater degree than men and they too had to be tamed and subdued for their own good and the good of the men they might tempt into sin’ (Stuart, 1996: 23). It is hardly surprising therefore that twentieth and twenty-first century feminist, womanist, mujerista and black theologians have worked hard to undo and re-express a theology of the body which offers a more authentic narrative of the relationship between the Divine and the physical which both liberates the female body and liberates God from the patriarchal box the Church has created around her.

…The female body can only be liberated from that patriarchal overwriting by writing its own narrative, much of which will be based upon experiences of being troubled. The true nature of the female body can only be revealed by a concerted effort to ‘re-own’ this body as our own not as we have been taught to understand it. This in turn means that the systems, doctrines and ‘ways of being’ which exist within the Church and society must be challenged and re-imagined from the perspective of the un-vocalized and troubled female narrative. In the sense that the female body has not really been ours, has not been an authentically female body and yet has the potential to be unlocked as such, it therefore makes for the perfect condition for metaxu, it is that thing which separates in its forms of oppression and connects in its potential liberation. It is at once a place where great evil has been wrought and a place of divine goodness. Weil writes of love that,

Creation is an act of love and it is perpetual. At each moment our existence is God’s love for us. But God can only love himself. His love for us is love for himself through us. Thus, he who gives us our being loves in us the acceptance of not being. Our existence is made up only of his waiting for our acceptance not to exist. He is perpetually begging from us that existence which he gives. He gives it to us in order to beg it from us (Weil, 2002: 28).

According to Weil, our very existence is from God and returns to God. I would argue that to be able to return this ‘not being’ to God, the body has to take some form of action, or have some form of action performed upon it to open a space in which our not being or not existing can be offered to God. It is this removal of our self which I argue can be interpreted as a removal of the socially created self to leave only the God part of ourselves, the authentic self that is God. The body is metaxu in that it is imperfect and yet perfect. The body is human and therefore unreal and socially recreated, yet the body is also created by God and God dwells within it. The female body is both imprisoned and is liberated. Its imprisonment is the very thing that enables it to unravel the layers of patriarchal construction to locate the God part and its imprisonment is the thing which allows for an authentic narrative to be written. The female body has to separate us from the Divine in order to connect us to the Divine.

Read the whole of this interesting paper by Charity Hamilton HERE.

ica 3rd space symposium at uct

L-R: jackï job, Dee Moholo, Koleka Putuma, Khanyi Mbongwa (Vasiki), Ilze Wolff, Lois Anguria

The most decolonised academic space I have yet had the joy of experiencing. The conference continues today. If you’re in Cape Town, come. It’s free!

HERE is the programme. 🌸

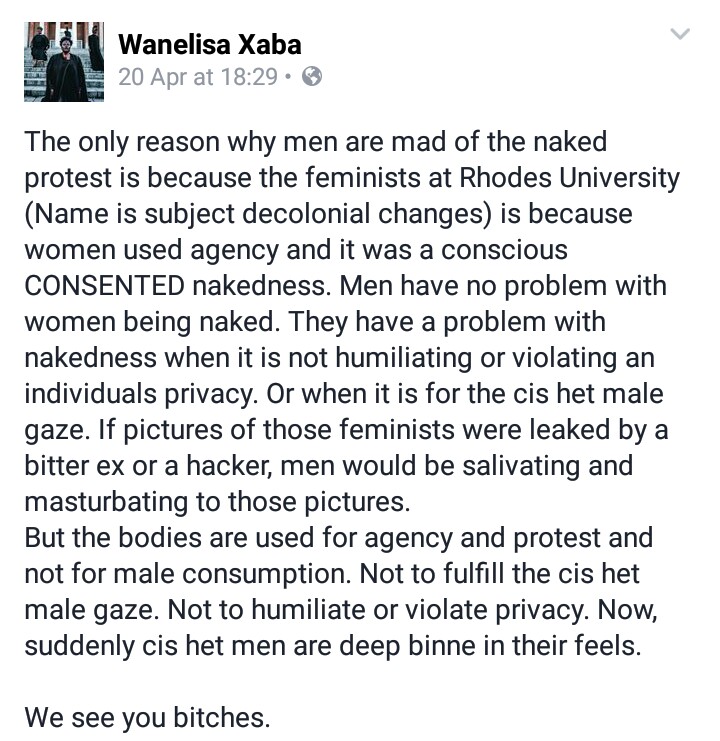

not for your gaze

george eliot (mary ann evans) – on being disagreeable

“George Eliot” was the pen name chosen by Mary Ann Evans, a Victorian writer. She chose a male pen name so that her works were taken seriously, in response to an 1856 essay she wrote for the Westminster Review, ‘Silly Novels by Lady Novelists’.

“George Eliot” was the pen name chosen by Mary Ann Evans, a Victorian writer. She chose a male pen name so that her works were taken seriously, in response to an 1856 essay she wrote for the Westminster Review, ‘Silly Novels by Lady Novelists’.

angelo fick on upholding rape culture in south africa

“In South Africa we have no business criticizing the young with homilies about propriety and dignity, decency and politesse. There can be no equality for young women in higher education if the spaces they are supposed to study in are organized around enabling their violation by omission, silence and inaction.

“In South Africa we have no business criticizing the young with homilies about propriety and dignity, decency and politesse. There can be no equality for young women in higher education if the spaces they are supposed to study in are organized around enabling their violation by omission, silence and inaction.

The shame does not reside with the survivors, despite the insults and abuse flung at them, despite the rubber bullets fired at them, despite being wrestled to the ground for daring to object to the normalization of and silence on their violence, and the inaction of organizations and institutions.”

– Angelo Fick, 20 April 2016. Read the full piece HERE.

jeannette ehlers – whip it good

This is an incredibly powerful performance.

Performances took place 24 – 30 April 2015, presented by Autograph ABP at Rivington Place, London. Presented in two parts, seven evening performances in the gallery followed by a seven-week exhibition, ‘Whip it Good’ retraces the footsteps of colonialism and maps the contemporary reverberations of the triangular slave trade via a series of performances that will result in a body of new ‘action’ paintings.

During each performance, the artist radically transforms the whip – a potent sign and signifier of violence against the enslaved body – into a contemporary painting tool, evoking within both the spectators and the participants the physical and visceral brutality of the transatlantic slave trade. Deep black charcoal is rubbed into the whip, directed at a large-scale white canvas, and – following the artist’s initial ritual – offered to members of the audience to complete the painting.

However, the themes that emerge from Whip It Good trace beyond those of slavery: Ehlers’ actions powerfully disrupt historical relationships between agency and control in the contemporary. The ensuing ‘whipped’ canvases become transformative bearers of the historical legacy of imperial violence, and through a controversial artistic act re-awaken critical debates surrounding gender, race and power within artistic production. What the process generates for the artist, is an intensely focused space in which to make new work as part of a cathartic collaborative process.

Read Chandra Frank’s review of the performance, which also took place in Gallery Momo in South Africa, HERE.

boat girls (2015)

Watch this short film, companion piece to the award-winning Keys, Money, Phone, starring Michelle Du Plessis, Amy Louise Wilson, and Sive Gubangxa.

Director: Roger Young

Producer: Shanna Freedman

DOP: Alfonzo Franke

Editor: Natalie Perel

Original Score: Nic Van Reenen

hélène cixous – castration or decapitation?

Hélène Cixous’ essay “Castration or Decapitation?” discusses the binary construction of sexuality and society, and how the feminine is defined by the negative: a woman is not a man because she lacks a penis. This “lack” keeps the female subject to definition by the male, as it is seen that because she is the “negative” pole to the man’s “positive”, the woman is concomitantly un-informed, and that therefore it is the position of the man to inform the woman. This imposed silence is what decapitates the feminine metaphorically, precluding her from speaking anything of meaning.

The following is an excerpt from this brilliant essay, translated by Annette Kuhn and published in Signs, Vol. 7, No. 1 (Autumn, 1981), pp. 41-55 (University of Chicago Press) – read the full essay HERE.

* * * * *