Category Archives: politics

reconciliation’s waste: heritage and waste in post-apartheid south africa

Analysis by Duane Jethro, one of my colleagues at the Archive and Public Culture Research Initiative.

By Duane Jethro

Svetlana Boym argues that ruins “make us think of the past that could have been and the future that never took place”. She turns the idea about the link between the past and the future around, and suggests we can use ruined or wasted things for clues about society in the present. In this piece I want to think about what certain ways of talking about waste and ruins in South Africa can tell us about pasts that never came to be and futures that never took place.

To do so means briefly thinking about heritage and reconciliation. Heritage, or the singling out of certain histories and people for commemoration, is connected to the idea of reconciliation, because in South Africa, it was meant to do the work of bringing South Africans together as a nation. Through new museums, statues and memorials, heritage would help overcome the long…

View original post 837 more words

not for your gaze

angelo fick on upholding rape culture in south africa

“In South Africa we have no business criticizing the young with homilies about propriety and dignity, decency and politesse. There can be no equality for young women in higher education if the spaces they are supposed to study in are organized around enabling their violation by omission, silence and inaction.

“In South Africa we have no business criticizing the young with homilies about propriety and dignity, decency and politesse. There can be no equality for young women in higher education if the spaces they are supposed to study in are organized around enabling their violation by omission, silence and inaction.

The shame does not reside with the survivors, despite the insults and abuse flung at them, despite the rubber bullets fired at them, despite being wrestled to the ground for daring to object to the normalization of and silence on their violence, and the inaction of organizations and institutions.”

– Angelo Fick, 20 April 2016. Read the full piece HERE.

findlay – the uct decolonisation project

From HERE.

hurray for the riff raff – the body electric

Read more HERE.

girl talk with nina

intersectional or bullshit

Press release from Wits Fees Must Fall:

Press release from Wits Fees Must Fall:

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: FEMINIST AND QUEER DISRUPTION OF WITS SHUTDOWN, 04 APRIL:

Today, 04 April 2016, a group of students attempted to shut down Wits University in the name of Wits Fees Must Fall. These students were comprised of some members of the Wits student body and other popular faces from the #Fallist movements throughout the country. Leaders of this movement have been quoted in media confirming the shutdown as an act in solidarity with suspended, intimidated and deregistered from Wits as of today, 04 April 2016 as well as the continued struggle against outsourcing of workers on university campuses.

Through reliable sources and substantive evidence, we know that the plan to shut down the Wits campus was discussed at a private symposium this past weekend, convened under the banner of Fess Must Fall, the invite to which was not extended to the broader Fees Must Fall movement on different campuses as well as the explicit exclusion of feminist and queer persons. The feminist and queer bodies that have continued to challenge the problematic and archaic investment in the institutions of patriarchal masculinities by student leaders who have continued to erase and silence their narratives and participation in the struggle for free decolonised education and outsourcing.

As a collective, the democratic process of convening and mandating members to attend Fees Must Fall related events has always been one that is consultative and open. The collective mandates representatives at each turn as the movement maintains a flat democratic structure. Therefore, the symposium of the past weekend, facilitated through external funders that seek to infiltrate the movement, and the employ of what we suspect to be non Wits students and members of the public, is one we do not recognise and refuse to be held hostage by its political dictates and ambitions.

We have maintained our integrity as an intersectional; student led non partisan movement that is fighting for free decolonised education and the insourcing of workers.

As a movement, we fully support the disruption of systems of power that have continued to exclude black students from accessing the higher education space as well as the outsourcing and dehumanisation of black workers on campuses. However, we will never tolerate a situation in which these disruptions are allowed to happen at the expense of queer and feminist bodies wherein their bodies are only utilised for the purposes of protecting heterosexual black men on the firing line.

Since the inception of the #Fallist movements, the student’s movements have been plagued by incidences and complaints of latent and rampant misogyny, sexism, patriarchy, homophobia and transmisogyny and this must come to an end. The disruption of the shut down this morning was a step towards disrupting this problematic trend where feminist and queer bodies are only good to be used for protecting heterosexual black men.

The revolution for a decolonised South Africa where free decolonised quality education is a reality for every Black child is one that feminist and queer bodies have maintained will be intersectional or it will not be a revolution at all. However, this afternoon, feminist and queer bodies were assaulted, strangled, kicked and beaten by these black men in the service of the black revolutionary project. Black feminist and queer bodies continue to put their bodies on the line and continue to be disregarded and erased by heterosexual black men.

This practise by heterosexual black men to sacrifice feminist and queer bodies in this revolution will not be tolerated any longer. The exclusion, abuse, assault and endangering of Black Feminist, Queer, Trans and Disabled bodies by heterosexual black men will no longer be tolerated.

All identities of Blackness will be included in this revolution or it will be bullshit!

To all Feminist, Queer, Trans and marginalised bodies, we are convening at the Revolutionary benches (Green benches in front of Umthombo Building) from 10:30 on 05 April 2016.

#NotMyFMF #FuckyourErasure #AllofUsorNoneofUs

intersectional or bullshit

creating a black archive – today at uct

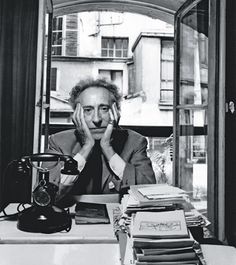

jean cocteau addresses the year 2000 (1962)

Compelling stuff.

Jean Cocteau began his career as a poet, publishing his first collection, Aladdin’s Lamp, at the age of 19. By 1963, at the age of 73, he had lived one of the richest artistic lives imaginable, transforming every genre he touched. Deciding to leave one last artefact to posterity, Cocteau sat down and recorded the film above, a message to the year 2000, intending it as a time capsule only to be opened in that year (though it was discovered, and viewed a few years earlier). Biographer James S. Williams describes the documentary testament as “Cocteau’s final gift to his fellow human beings.”

Portraying himself as “a living anachronism” in a “phantom-like state,” Cocteau, seated before his own artwork, quotes St. Augustine, makes parables of events in his life, and addresses, primarily, the youth of the future. The uses and misuses of technology comprise a central theme of his discourse: “I certainly hope that you have not become robots,” Cocteau says, “but on the contrary that you have become very humanized: that’s my hope.” The people of his time, he claims, “remain apprentice robots.”

Among Cocteau’s concerns is the dominance of an “architectural Esperanto, which remains our time’s great mistake.” By this phrase he means that “the same house is being built everywhere and no attention is paid to climate, atmospherical conditions or landscape.” Whether we take this as a literal statement or a metaphor for social engineering, or both, Cocteau sees the condition as one in which these monotonous repeating houses are “prisons which lock you up or barracks which fence you in.” The modern condition, as he frames it, is one “straddling contradictions” between humanity and machinery. Nonetheless, he is impressed with scientific advancement, a realm of “men who do extraordinary things.”

And yet, “the real man of genius,” for Cocteau, is the poet, and he hopes for us that the genius of poetry “hasn’t become something like a shameful and contagious sickness against which you wish to be immunized.” He has very much more of interest to communicate, about his own time, and his hopes for ours. Cocteau recorded this transmission from the past in August of 1963. On October 11 of that same year, he died of a heart attack, supposedly shocked to death by news of his friend Edith Piaf’s death that same day in the same manner.

And yet, “the real man of genius,” for Cocteau, is the poet, and he hopes for us that the genius of poetry “hasn’t become something like a shameful and contagious sickness against which you wish to be immunized.” He has very much more of interest to communicate, about his own time, and his hopes for ours. Cocteau recorded this transmission from the past in August of 1963. On October 11 of that same year, he died of a heart attack, supposedly shocked to death by news of his friend Edith Piaf’s death that same day in the same manner.

His final film, and final communication to a public yet to be born, accords with one of the great themes of his life’s work—“the tug of war between the old and the new and the paradoxical disparities that surface because of that tension.” Should we attend to his messages to our time, we may find that he anticipated many of our 21st century dilemmas between technology and humanity, and between history and myth. It’s interesting to imagine how we might describe our own age to a later generation, and, like Cocteau, what we might hope for them.

Via Open Culture.

walter benjamin – surrealism: the last snapshot of the european intelligentsia (1929)

… There is always, in such movements, a moment when the original tension of the secret society must either explode in a matter-of-fact, profane struggle for power and domination, or decay as a public demonstration and be transformed. Surrealism is in this phase of transformation at present. But at the time when it broke over its founders as an inspiring dream wave, it seemed the most integral, conclusive, absolute of movements. Everything with which it came into contact was integrated. Life only seemed worth living where the threshold between waking and sleeping was worn away in everyone as by the steps of multitudinous images flooding back and forth, language only seemed itself where, sound and image, image and sound interpenetrated with automatic precision and such felicity that no chink was left for the penny-in-the-slot called ‘meaning’.

Image and language take precedence. Saint-Pol Roux, retiring to bed about daybreak, fixes a notice on his door: ‘Poet at work.’ Breton notes: ‘Quietly. I want to pass where no one yet has passed, quietly! After you, dearest language.’ Language takes precedence. Not only before meaning. Also before the self. In the world’s structure dream loosens individuality like a bad tooth. This loosening of the self by intoxication is, at the same time, precisely the fruitful, living experience that allowed these people to step outside the domain of intoxication.

This is not the place to give an exact definition of Surrealist experience. But anyone who has perceived that the writings of this circle are not literature but something else – demonstrations, watchwords, documents, bluffs, forgeries if you will, but at any rate not literature – will also know, for the same reason, that the writings are concerned literally with experiences, not with theories and still less with phantasms. And these experiences are by no means limited to dreams, hours of hashish eating, or opium smoking. It is a cardinal error to believe that, of ‘Surrealist experiences’, we know only the religious ecstasies or the ecstasies of drugs. The opium of the people, Lenin called religion, and brought the two things closer together than the Surrealists could have liked.

I shall refer later to the bitter, passionate revolt against Catholicism in which Rimbaud, Lautreamont, and Apollinaire brought Surrealism into the world. But the true creative overcoming of religious illumination certainly does not lie in narcotics. It resides in a profane illumination, ‘a materialistic, anthropological inspiration, to which hashish, opium, or whatever else can give an introductory lesson. (But a dangerous one; and the religious lesson is stricter.)

This profane illumination did not always find the Surrealists equal to it, or to themselves, and the very writings that proclaim it most powerfully, Aragon’s incomparable Paysan de Paris and Breton’s Nadja, show very disturbing symptoms of deficiency. For example, there is in Nadja an excellent passage on the ‘delightful days spent looting Paris under the sign of Sacco and Vanzetti’; Breton adds the assurance that in those days Boulevard Bonne-Nouvelle fulfilled the strategic promise of revolt ‘that had always been implicit in its name. But Madame Sacco also appears, not the wife of Fuller’s victim but avoyante, a fortune-teller who lives at 3 rue des Usines and tells Paul Eluard that he can expect no good from Nadja.

Now I concede that the breakneck career of Surrealism over rooftops, lightning conductors, gutters, verandas, weathercocks, stucco work – all ornaments are grist to the cat burglar’s mill- may have taken it also into the humid backroom of spiritualism. But I am not pleased to hear it cautiously tapping on the window-panes to inquire about its future. Who would not wish to see these adoptive children of revolution most rigorously severed from all the goings-on in the conventicles of down-at-heel dowagers, retired majors, and emigre profiteers?

In other respects Breton’s book illustrates well a number of the basic characteristics of this ‘profane illumination’. He calls Nadja ‘a book with a banging door’. (In Moscow I lived in a hotel in which almost all the rooms were occupied by Tibetan lamas who had come to Moscow for a congress of Buddhist churches. I was struck by the number of doors in the corridors that were always left ajar. What had at first seemed accidental began to be disturbing. I found out that in these rooms lived members of a sect who had sworn never to occupy closed rooms. The shock I had then must be felt by the reader of Nadja.)

To live in a glass house is a revolutionary virtue par excellence. It is also an intoxication, a moral exhibitionism, that we badly need. Discretion concerning one’s own existence, once an aristocratic virtue, has become more and more an affair of petty-bourgeois parvenus. Nadja has achieved the true, creative synthesis between the art novel and the roman-a-clef.

Moreover, one need only take love seriously to recognize in it, too – as Nadja also indicates – a ‘profane illumination’. ‘At just that time’ (i.e., when he knew Nadja), the author tells us, ‘I took a great interest in the epoch of Louis VII, because it was the time of the ‘courts of love’, and I tried to picture with great intensity how people saw life then.’ We have from a recent author quite exact information on Provencal love poetry, which comes surprisingly close to the Surrealist conception of love. ‘All the poets of the ‘new style’,’ Erich Auerback points out in his excellent Dante: Poet of the Secular World, ‘possess a mystical beloved, they all have approximately the same very curious experience of love; to them all Amor bestows or withholds gifts that resemble an illumination more than sensual pleasure; all arc subject to a kind of secret bond that determines their inner and perhaps also their outer-lives’. The dialectics of intoxication are indeed curious. Is not perhaps all ecstasy in one world humiliating sobriety in that complementary to it? What is it that courtly Minne seeks, and it, not love, binds Breton to the telepathic girl, if not to make chastity, too, a transport? Into a world that borders not only on tombs of the Sacred Heart or altars to the Virgin, but also on the morning before a battle or after a victory.

The lady, in esoteric love, matters least. So, too, for Breton. He is closer to the things that Nadja is close to than to her. What are these things? Nothing could reveal more about Surrealism than their canon.Where shall I begin? He can boast an extraordinary discovery. He was the first to perceive the revolutionary energies that appear in the ‘outmoded’, in the first iron constructions, the first factory buildings, the earliest photos, the objects that have begun to be extinct, grand pianos, the dresses of five years ago, fashionable restaurants when the vogue has begun to ebb from them. The relation of these things to revolution, no one can have a more exact concept of it than these authors. No one before these visionaries and augurs perceived how destitution – not only social but architectonic, the poverty of interiors/enslaved and enslaving objects – can be suddenly transformed into revolutionary nihilism. Leaving aside Aragon’s Passage de I’Opera, Breton and Nadja are the lovers who convert everything that we have experienced on mournful railway journeys (railways are beginning to age), on Godforsaken Sunday afternoons in the proletarian quarters of the great cities, in the first glance through the rain-blurred window of a new apartment, into revolutionary experience, if not action. They bring the immense forces of ‘atmosphere’ concealed in these things to the point of explosion. What form do you suppose a life would take that was determined at a decisive moment precisely by the street song last on everyone’s lips?thuto-lesedi gaasenwe – dear mr president

seminar at huma (uct) tomorrow

susan buck-morss on work in the age of mechanical reproduction

Susan Buck-Morss, writing in 2001 on Walter Benjamin’s philosophy of history, marked by the critique of progress in the name of a revolutionary time which interrupts history’s chronological continuum:

The only power available to us as we, riding in the train of history, reach for the emergency brake, is the power that comes from the past… One fact of the past that we particularly are in danger of forgetting is the apparent harmlessness with which the process of cultural capitulation takes place. lt is a matter, simply, of wanting to keep up with the intellectual trends, to compete in the marketplace, to stay relevant, to stay in fashion…

So, what in God’s name are we doing here? The litmus test for intellectual production is how it affects the outside world, not what happens inside an academic enclave such as this one. [Walter] Benjamin himself held up as the criterion for his work that it be “totally useless for the purpose of Fascism.”* Could any of us say of our work that it is totally useless for the purposes of the new global order, in which class exploitation is blatant, but the language to describe it is in ruins? Of course, we would be horrified if decisions on academic hiring and promotion were made on the basis of what our work contributed to the class struggle. The disturbing truth, however, is that these decisions are already being made on the basis of ensuring that our work contributes nothing to the class struggle. And that, my friends, is problematic.

__

*Benjamin, preface to ‘Work in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”. In: Benjamin 1969: 2 18.

__

In Pandaemonium Germanicum, 5/2001, pp. 73-88. Read the full article: Susan Buck-Morss – Walter Benjamin – between academic fashion and the Avant Garde.

unholy ghosts

Modernity was built upon ‘technologies that made us all ghosts’, and postmodernity could be defined as the succumbing of historical time to the spectral time of recording devices. Postmodernity screens out the spectrality, naturalising the uncanniness of the recording apparatuses. Anyone hearing a recording of their own voice or seeing a photograph of themselves is presented with a double. The uncanny thought, often repressed or forgotten, is that the recordings and the photographs will survive us; that as we contemplate them, we are put in the position of a ghost.

— From “Phonograph Blues” by k-punk, from a decade-old blog I love, HERE.

homo sacer

A really clear, simplified explanation of Giorgio Agamben‘s discussion of Homo sacer: someone forcibly reduced to bare life, cf. Simone Weil’s forcible destruction of the “I”.

Read also Achille Mbembe on people reduced to being conceived of as surplus or waste:

“Perhaps to a degree hardly achieved in the rest of the Continent, the human has consistently taken on the form of waste within the peculiar trajectory race and capitalism espoused in South Africa. Traditionally, we speak of “waste” as something produced bodily or socially by humans. In this sense, “waste” is that which is other than the human. Traditionally too, we speak of the intrinsic capacity of capitalism to waste human lives. We speak of how workers are wasted under capitalism in comparable fashion to natural resources. Marx in particular characterizes capitalist production as thoroughly wasteful with what he calls “human material” just as it is with “material resources”. It squanders “human beings, living labour”, “squandering not only flesh and blood, but nerves and brain, life and health as well”, he writes. In order to grasp the particular drama of the human in the history of South Africa, we should broaden this traditional definition of “waste” and consider the human itself as a waste product at the interface of race and capitalism. Squandering and wasting black lives has been an intrinsic part of the logic of capitalism, especially in those contexts in which race is central to the simultaneous production of wealth and of superfluous people…

… One of the most brutal effects of neo-liberalism in South Africa has been the generalization and radicalization of a condition of temporariness for the poor. For many people, the struggle to be alive has taken the form of a struggle against the constant corrosion of the present, both by change and by uncertainty.

In order to reanimate the idea of “the human” in contemporary South African politics and culture, there is therefore no escape from the need to reflect on the thoroughly political and historical character of wealth and property and the extent to which wealth and property have come to be linked with bodily life.”

And HERE is another discussion, by Richard Pithouse, which further sets out the colonial history of the discourse around people in a state of exception (in the context of shack dwellers).

on words and power

The problem of language is at the heart of all the struggles between the forces striving to abolish the present alienation and those striving to maintain it. It is inseparable from the very terrain of those struggles.

We live within language as within polluted air. Despite what humorists think, words do not play. Nor do they make love, as Breton thought, except in dreams. Words work — on behalf of the dominant organization of life. Yet they are not completely automated: unfortunately for the theoreticians of information, words are not in themselves “informationist”; they contain forces that can upset the most careful calculations.

Words coexist with power in a relation analogous to that which proletarians (in the modern as well as the classic sense of the term) have with power. Employed by it almost full time, exploited for every sense and nonsense that can be squeezed out of them, they still remain in some sense fundamentally alien to it.

~ From “All the King’s Men”, which originally appeared in Internationale Situationniste #8 (Paris, January 1963). This translation by Ken Knabb is from the Situationist International Anthology (Revised and Expanded Edition, 2006). No copyright.

Read the rest of this statement HERE.

white noise

jeannette ehlers – whip it good

This is an incredibly powerful performance.

Performances took place 24 – 30 April 2015, presented by Autograph ABP at Rivington Place, London. Presented in two parts, seven evening performances in the gallery followed by a seven-week exhibition, ‘Whip it Good’ retraces the footsteps of colonialism and maps the contemporary reverberations of the triangular slave trade via a series of performances that will result in a body of new ‘action’ paintings.

During each performance, the artist radically transforms the whip – a potent sign and signifier of violence against the enslaved body – into a contemporary painting tool, evoking within both the spectators and the participants the physical and visceral brutality of the transatlantic slave trade. Deep black charcoal is rubbed into the whip, directed at a large-scale white canvas, and – following the artist’s initial ritual – offered to members of the audience to complete the painting.

However, the themes that emerge from Whip It Good trace beyond those of slavery: Ehlers’ actions powerfully disrupt historical relationships between agency and control in the contemporary. The ensuing ‘whipped’ canvases become transformative bearers of the historical legacy of imperial violence, and through a controversial artistic act re-awaken critical debates surrounding gender, race and power within artistic production. What the process generates for the artist, is an intensely focused space in which to make new work as part of a cathartic collaborative process.

Read Chandra Frank’s review of the performance, which also took place in Gallery Momo in South Africa, HERE.

scott woods on the structural nature of whiteness and racism

The problem is that white people see racism as conscious hate, when racism is bigger than that. Racism is a complex system of social and political levers and pulleys set up generations ago to continue working on the behalf of whites at other people’s expense, whether whites know/like it or not. Racism is an insidious cultural disease. It is so insidious that it doesn’t care if you are a white person who likes Black people; it’s still going to find a way to infect how you deal with people who don’t look like you.

Yes, racism looks like hate, but hate is just one manifestation. Privilege is another. Access is another. Ignorance is another. Apathy is another, and so on. So while I agree with people who say no one is born racist, it remains a powerful system that we’re immediately born into. It’s like being born into air: you take it in as soon as you breathe.

It’s not a cold that you can get over. There is no anti-racist certification class. It’s a set of socioeconomic traps and cultural values that are fired up every time we interact with the world. It is a thing you have to keep scooping out of the boat of your life to keep from drowning in it. I know it’s hard work, but it’s the price you pay for owning everything.

~ Scott Woods

More HERE.

boat girls (2015)

Watch this short film, companion piece to the award-winning Keys, Money, Phone, starring Michelle Du Plessis, Amy Louise Wilson, and Sive Gubangxa.

Director: Roger Young

Producer: Shanna Freedman

DOP: Alfonzo Franke

Editor: Natalie Perel

Original Score: Nic Van Reenen

macklemore & ryan lewis feat. jamila woods – white privilege II

THIS. This is so on point.

bright blue – weeping

An honest song about the violence of white fear, and sadly just as relevant as ever.

how to respond

This is so often a problem, as I see it: that white people, particularly men, tend not to seek to understand other points of view before feeling entitled to give theirs. If listening feels hard, maybe you need to do it more.

how mainstream media unknowingly helps the anc use zuma as its racial jesus

“[W]hat will shape South Africa’s political destiny is not “the truth” but the careful navigation and understanding of how words are digested by those watching and listening.”

A deeply perceptive piece by Siya Khumalo about how South Africans are talking past one another.

Almost everyone on my Facebook has been asking the same question: how did the #ZumaMustFallMarch become about race? Isn’t it clear that the current president is bad news for the country?

Jacob Zuma – the person and the president, the body that is depicted visually and the figure that is related to politically – is the terrain on which South Africa’s race issues have played themselves out in weird and telling ways. Without realising it, mainstream media has done the ANC a huge favour in playing up the DA’s “Zuma is corrupt” trope because as well-intentioned and truthful as it may be, what it’s done is exacerbate the friction among the races – especially between black and white people – because white people do not know how to level an insult so it lands where it’s intended. This is because colonialism and apartheid skewed racial relations.

Let’s say Jacob Zuma…

View original post 1,436 more words

la tristesse durera

#takebackthevoid

From HERE.

a luta continua

for the “treasonous”, the belville 6 – by ameera conrad

He stood in front of us

held his palms up

be calm comrades

sit down comrades

do not do anything to antagonise them

Comrades.

They knew his face, though we could not see him between the arms of a chokehold.

He sat on the floor among us

legs crossed under him

Senzeni na?

Senzeni na?

They stunned us, clicked tazers.

White-police-coward-not-man

pulled him out and away.

Another chokehold.

He fell to the floor

when the first grenade cracked

through the crowd.

Pulled up and bashed against shields

holding his burned face

dragged across the gravel.

Senzeni na?

He sat on the steps

quietly

consoling comrades

away from the crowd

They ripped him to his feet

he showed his empty palms

into the back of a van.

No fists.

Empty palms.

He held his hands over his head.

He held his empty hands over his head.

He held his open palms over his head.

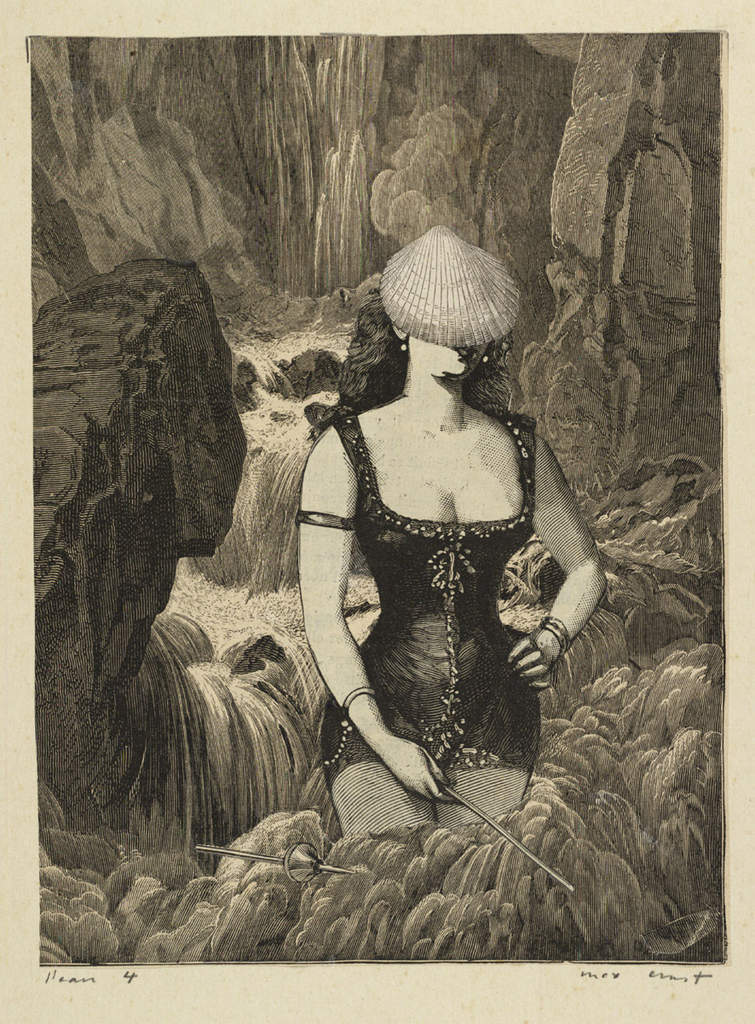

He held his head.

![Max Ernst - Une semaine de bonté [A Week of Kindness]. La clé des chants 1 [The Key of Songs 1] 1933](https://fleurmach.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/003_max_ernst_theredlist.jpg?w=869)