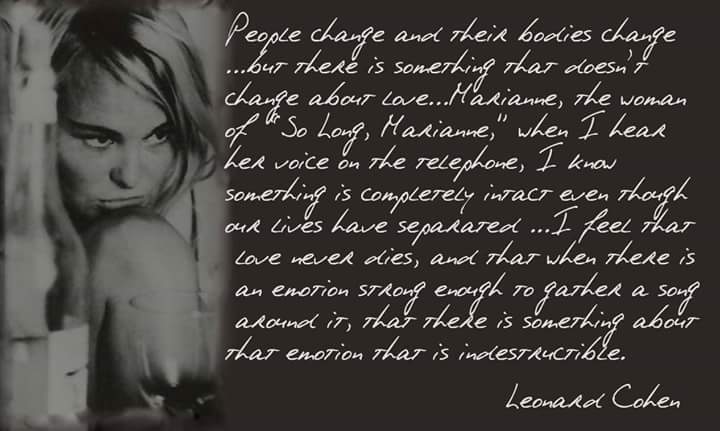

so long, marianne…

Leonard Cohen’s Marianne died last week. Two days before she left earth, he sent her a beautiful letter.

“Well, Marianne, it’s come to this time when we are really so old and our bodies are falling apart and I think I will follow you very soon. Know that I am so close behind you that if you stretch out your hand, I think you can reach mine.

“And you know that I’ve always loved you for your beauty and your wisdom, but I don’t need to say anything more about that because you know all about that. But now, I just want to wish you a very good journey. Goodbye old friend. Endless love, see you down the road.”

Read more here.

Observatory, Cape Town, Friday 5 August 2016.

patti smith – kimberly (1975)

The wall is high, the black barn,

The babe in my arms in her swaddling clothes

And I know soon that the sky will split

And the planets will shift,

Balls of jade will drop and existence will stop.

Little sister, the sky is falling, I don’t mind, I don’t mind.

Little sister, the fates are calling on you.

Ah, here I stand again in this old ‘lectric whirlwind,

The sea rushes up my knees like flame

And I feel like just some misplaced Joan Of Arc

And the cause is you lookin’ up at me.

Oh baby, I remember when you were born,

It was dawn and the storm settled in my belly

And I rolled in the grass and I spit out the gas

And I lit a match and the void went flash

And the sky split and the planets hit,

Balls of jade dropped and existence stopped, stopped, stop, stop.

Little sister, the sky is falling, I don’t mind, I don’t mind.

Little sister, the fates are calling on you.

I was young ‘n crazy, so crazy I knew I could break through with you,

So with one hand I rocked you and with one heart I reached for you.

Ah, I knew your youth was for the takin’, fire on a mental plane,

So I ran through the fields as the bats with their baby vein faces

Burst from the barn and flames in a violent violet sky,

And I fell on my knees and pressed you against me.

Your soul was like a network of spittle,

Like glass balls movin’ in like cold streams of logic,

And I prayed as the lightning attacked

That something will make it go crack, something will make it go crack,

Something will make it go crack, something will make it go crack.

The palm trees fall into the sea,

It doesn’t matter much to me

As long as you’re safe, Kimberly.

And I can gaze deep

Into your starry eyes, baby, looking deep in your eyes, baby,

Looking deep in your eyes, baby, looking deep in your eyes, baby,

Into your starry eyes, oh.

Oh, in your starry eyes, baby,

Looking deep in your eyes, baby, looking deep in your eyes, baby, oh.

Oh, looking deep in your eyes, baby,

Into your starry eyes, baby, looking deep in your eyes, baby…

—

Simon Reynolds in a fascinating discussion with Patti Smith of her Horses album here.

joanna newsom – time, as a symptom (2015)

Time passed hard,

and the task was the hardest thing she’d ever do.

But she forgot,

the moment she saw you.

So it would seem to be true:

when cruel birth debases, we forget.

When cruel death debases,

we believe it erases all the rest

that precedes.

But stand brave, life-liver,

bleeding out your days

in the river of time.

Stand brave:

time moves both ways,

in the nullifying, defeating, negating, repeating

joy of life;

the nullifying, defeating, negating, repeating

joy of life.

The moment of your greatest joy sustains:

not axe nor hammer,

tumor, tremor,

can take it away, and it remains.

It remains.

And it pains me to say, I was wrong.

Love is not a symptom of time.

Time is just a symptom of love

(and the nullifying, defeating, negating, repeating

joy of life;

the nullifying, defeating, negating, repeating

joy of life).

Hardly seen, hardly felt–

deep down where your fight is waiting,

down ’till the light in your eyes is fading:

joy of life.

Where i know that you can yield, when it comes down to it;

bow like the field when the wind combs through it:

joy of life.

And every little gust that chances through

will dance in the dust of me and you,

with joy-of-life.

And in our perfect secret-keeping:

One ear of corn,

in silent, reaping

joy of life.

Joy! Again, around–a pause, a sound–a song:

a way a lone a last a loved a long.

A cave, a grave, a day: arise, ascend.

(Areion, Rharian, go free and graze. Amen.)

A shore, a tide, unmoored–a sight, abroad:

A dawn, unmarked, undone, undarked (a god).

No time. No flock. No chime, no clock. No end.

White star, white ship–Nightjar, transmit: transcend!

White star, white ship–Nightjar, transmit: transcend!

White star, white ship–Nightjar, transmit: transcend!

White star, white ship–Nightjar, transmit: trans

Much has been made, in almost all recent profiles and in earlier reviews, of the optimistically transcendent cyclicality of the “final” gesture on Newsom’s exquisite new album, Divers — her first in five years. But gauging the (potentially inconclusive) philosophical conclusion — one that could also be wholly cynical — of Divers really comes down to how the listener decides to experience its last song, “Time, as a Symptom.”

The album’s ending is not unlike the “Isn’t this where we came in?” conclusion/introduction to Pink Floyd’s The Wall, except even more abrupt, given that Newsom cuts herself off in the middle of a single word. The word in question — “transcending” — wraps around at the start of the album’s first song.

Set your iTunes to loop and it’ll join the album’s hanging final prefix, “trans—” and opening word, “sending.” It’ll likewise connect the similar sylvan soundbites underscoring these two moments (varied birdcalls and the technicolor fog of the album’s cover rendered in sound), joining the first and last tracks in a form of rebirth in a way that, as NPR put it, “lift[s] the spirit aloft.” Listen to it on vinyl and you may hear how “trans” and “sending” attempt, now perhaps futilely, to reach back and forth through your own memory of the opening of the album, to connect. Listen to the song on its own on, say, YouTube, and the end is an almost violent death of a close, cutting off the singer’s last command, “transcend,” as though she’s vocalizing her own — and everyone else’s own — fatal failure to do so. Like most of Newsom’s music, she leaves the meaning of the album’s culmination — and the light or despairing shadow it casts on the rest of it — ambiguous.

Throughout the album, Newsom appears rigorously aware, on both minute and cosmic scales, of the shifting ontological implications of our times, as well as their potential fallacy, and the possibility that some factors of human life — like altering time’s tyranny over it — may never truly change. The current human experience is underscored by new polarities of doom and transcendent life: possibilities of immortality via “the Singularity” versus imminent death via global warming, particle colliders showing us how space-time can be bent versus particle colliders destroying us, the Internet as the birth of a more universalist world versus the Internet as the death of the physical world. Even more than artists who’ve been lauded for eliciting the emotional spectra of humans who’ve melded with machines, Newsom has, with her bounty of antiquated instruments, made an album that unquestionably sounds like today…

…Divers is a monumental album in which monuments are brought up for their proneness to crumble, their inability to remain beyond their — as a line in “Waltz of the 101st Lightborne” goes — “great simulacreage.” But it wonders, with the ultimate inconclusiveness of that last line, if the physical/temporal restraints on the human condition could shift. In “Sapokanikan,” Newsom sings that “the causes we die for are lost in the idling bird call.” And so perhaps it’s best to say that there’s both victory and despair, existing as parallel possibilities, when the album ends with either a death or a transcendence, underscored by birdcalls — the indifferent, (and especially as Jonathan Franzen likes to point out, also fleeting) presences that are left. The question it leaves open — as it simultaneously creates a tragic death and a transcendent bridge — is one that makes Divers one of the affecting reflections of our philosophical, scientific and emotional moment recently made into an album.

Read the rest of this review at Flavorwire.

henry van dyke on doing things

“Use what talents you possess; the woods would be very silent if no birds sang there except those that sang best.”

big mama thornton – everything gonna be alright

This performance though…

tonight

I wish right now that I could spew a wry little poem, like those you do

But what’s churning round in me is only a terribly fervent prayer:

Please get home safely through this rain

Please can neither of us die

Before we are friends again

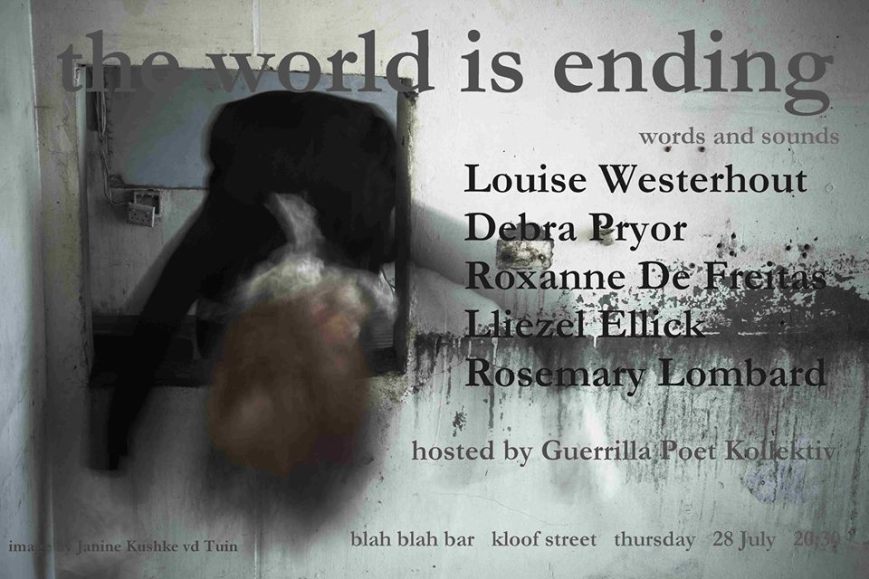

note to self (live at the blah blah bar)

A poem by Louise Westerhout, accompanied by Lliezel Ellick (cello) and Rosemary Lombard (autoharp), performed on 28 July 2016 at the Blah Blah Bar’s Open Mouth night.

Next time we’ll make sure we find a venue where rude men at the bar are not entitled to talk through performances…

gloomy sunday (live at the blah blah bar)

A version of the Rezsö Seress classic that we performed on 28 July 2016 as part of a collective which included Louise Westerhout, Lliezel Ellick, Rosemary Lombard, Debra Pryor and Roxanne de Freitas, at Blah Blah Bar’s “Open Mouth” night. We had had just two rehearsals, and I feel like this has the potential to go a lot further… Watch this space!

“the widow’s jar” – an automaton by thomas kuntz (2016)

The most wondrous stuff regularly comes up in my feeds, as if in direct response to my posts, but not – here’s an example. If it’s all coincidence, I’m very lucky.

Check out Thomas Kuntz’s site for more of his incredible automata.

massive attack feat. hope sandoval – paradise circus (2010)

From Heligoland, released in 2010, with vocals by Hope Sandoval.

Also check out the epic 2011 remix by Burial:

And this one from Gui Boratto:

massive attack feat. elizabeth fraser – black milk (1998)

From their album Mezzanine. . Incorporates a sample from Manfred Mann’s Earth Band’s track, “Tribute“, for which Massive Attack were sued.

massive attack feat. ghostpoet – come near me (2016)

Brand new video published on Friday.

hans richter/the real tuesday weld – one more ghost before breakfast (1927/2005)

Hans Richter’s 1927 short Dadaist masterpiece: Ghosts Before Breakfast, re-scored.

“This film initially had a soundtrack which was lost when the original print was destroyed by the Nazis as ‘degenerate art’.

This music – with Jacques Van Rhijn on clarinet, Don Brosnan on bass, Jed Woodhouse on drums, Clive Painter on guitar – was recorded at Clive’s prior to the sessions for our re-score of Richter’s full length magnum opus: Dreams That Money Can Buy for the British Film Institute in 2005.

(Turn off the sound if you want to hear it as Richter didn’t really intend it.)”

marek skrobecki – danny boy (2011)

keeping time at uct, 2 august 2016

This coming Tuesday, find out more about the extraordinary archive of photographs and live recordings made by Ian Bruce Huntley in the 1960s and early 1970s. In 2013 I was involved in putting this archive of recordings online, which you can explore HERE.

Keeping Time: Ian Bruce Huntley’s South African jazz archive

by Jonathan Eato

Ian Bruce Huntley is not a name that you’ll find readily in the burgeoning annals of South African jazz. Unless, that is, you talk to the dwindling generation of jazz musicians who were working in South Africa in the mid-1960s. Tete Mbambisa remembers Huntley as the man who ‘recorded our gold’, and this Huntley did through a series of remarkable photographic images and live audio recordings. Having privately preserved these records for over forty years, throughout the state repression of grand-apartheid and into the democratic era, they have recently been made available for the first time.

This talk will consider how, in the face of increasing political oppression, Huntley’s archive documented a community of vernacular intellectuals exploring and developing ideas in counterpoint to much commercially available South African jazz post-‘Pondo Blues’.

For more info:

email: ems@uct.ac.za

tel: 021 650 2888

Facebook event HERE.

On set at Muti Films tonight.

lotte lenya – lost in the stars

Lost in the Stars is a musical with score by Kurt Weill, based on the novel Cry, the Beloved Country (1948) by Alan Paton. The musical premiered on Broadway in 1949; it was the composer’s last work for the stage before he died the following year.

EDIT: The live performance I originally posted was removed from YouTube. Here is another version.

the real tuesday weld – the ghosts (2011)

Off The Last Werewolf, (2011, Six Degrees Records / Crammed Discs).

Soundtrack/companion album to the novel The Last Werewolf by Glen Duncan.

the real tuesday weld – me and mr wolf (2011)

Produced By: Monkey Frog Media

Music By: The Real Tuesday Weld

Published by: Six Degrees Records & Crammed Disks

the real tuesday weld – tear us apart (2011)

Alex De Campi’s stop motion fairytale epic for “Tear Us Apart” from the album The Last Werewolf .

clara rockmore – nocturne in c# minor (1975)

ruth white – spleen (1969)

From her 1969 album of interpretations of Baudelaire’s poetry, Flowers of Evil.

jacky bowring – a field guide to melancholy (2008)

“Melancholy is a twilight state; suffering melts into it and becomes a sombre joy. Melancholy is the pleasure of being sad.”

– Victor Hugo, Toilers of the Sea

Melancholy is ambivalent and contradictory. Although it seems at once a very familiar term, it is extraordinarily elusive and enigmatic. It is something found not only in humans – whether pathological, psychological, or a mere passing mood – but in landscapes, seasons, and sounds. They too can be melancholy. Batman, Pierrot, and Hamlet are all melancholic characters, with traits like darkness, unrequited longing, and genius or heroism. Twilight, autumn and minor chords are also melancholy, evoking poignancy and the passing of time.

How is melancholy defined? A Field Guide to Melancholy traces out some of the historic traditions of melancholy, most of which remain today, revealing it to be an incredibly complex term. Samuel Johnson’s definition, in his eighteenth century Dictionary of the English Language, reveals melancholy’s multi-faceted nature was already well established by then: ‘A disease, supposed to proceed from a redundance of black bile; a kind of madness, in which the mind is always fixed on one object; a gloomy, pensive, discontented temper.’2 All of these aspects – disease, madness and temperament – continue to coalesce in the concept of melancholy, and rather than seeking a definitive definition or chronology, or a discipline-specific account, this book embraces contradiction and paradox: the very kernel of melancholy itself.

As an explicit promotion of the ideal of melancholy, the Field Guide extols the benefits of the pursuit of sadness, and questions the obsession with happiness in contemporary society. Rather than seeking an ‘architecture of happiness’, or resorting to Prozac-with-everything, it is proposed that melancholy is not a negative emotion, which for much of history it wasn’t – it was a desirable condition, sought for its ‘sweetness’ and intensity. It remains an important point of balance – a counter to the ‘loss of sadness’. Not grief, not mourning, not sorrow, yet all of those things.

Melancholy is profoundly interdisciplinary, and ranges across fields as diverse as medicine, literature, art, design, psychology and philosophy. It is over two millennia old as a concept, and its development predates the emergence of disciplines.While similarly enduring concepts have also been tackled by a breadth of disciplines such as philosophy, art and literature, melancholy alone extends across the spectrum of arts and sciences, with significant discourses in fields like psychiatry, as much as in art. Concepts with such an extensive period of development (the idea of ‘beauty’ for example) tend to go through a process of metamorphosis and end up meaning something distinctly different.3 Melancholy has been surprisingly stable. Despite the depth and breadth of investigation, the questions, ideas and contradictions which form the ‘constellation’4 of melancholy today are not dramatically different from those at any time in its history. There is a sense that, as psychoanalytical theorist Julia Kristeva puts it, melancholy is ‘essential and trans-historical’.5

Melancholy is a central characteristic of the human condition, and Hildegard of Bingen, the twelfth century abbess and mystic, believed it to have been formed at the moment that Adam sinned in taking the apple – when melancholy ‘curdled in his blood’.6 Modern day Slovenian philosopher, Slavoj Žižek, also positions melancholy, and its concern with loss and longing, at the very heart of the human condition, stating ‘melancholy (disappointment with all positive, empirical objects, none of which can satisfy our desire) is in fact the beginning of philosophy.’7

The complexity of the idea of melancholy means that it has oscillated between attempts to define it scientifically, and its embodiment within a more poetic ideal. As a very coarse generalisation, the scientific/psychological underpinnings of melancholy dominated the early period, from the late centuries BC when ideas on medicine were being formulated, while in later, mainly post-medieval times, the literary ideal became more significant. In recent decades, the rise of psychiatry has re-emphasised the scientific dimensions of melancholy. It was never a case of either/or, however, and both ideals, along with a multitude of other colourings, have persisted through history.

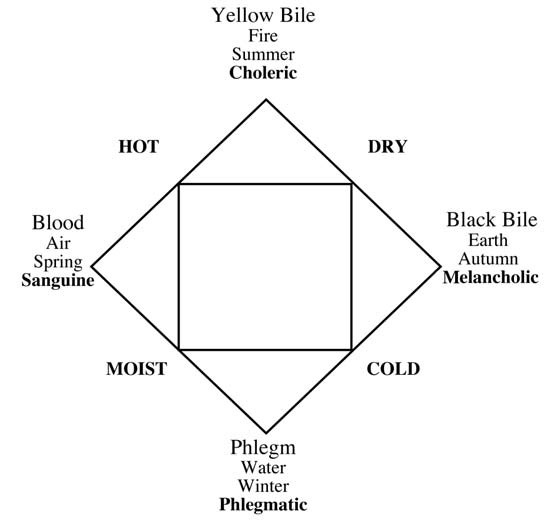

The essential nature of melancholy as a bodily as well as a purely mental state is grounded in the foundation of ideas on physiology; that it somehow relates to the body itself. These ideas are rooted in the ancient notion of ‘humours’. In Greek and Roman times humoralism was the foundation for an understanding of physiology, with the four humours ruling the body’s characteristics.

Phlegm, blood, yellow bile and black bile were believed to be the four governing elements, and each was ascribed to particular seasons, elements and temperaments. This can be expressed via a tetrad, or four-cornered diagram.

The Four Humours, adapted from Henry E Sigerist (1961) “A History of Medicine”, 2 vols New York: Oxford University Press, 2:232

The four-part divisions of temperament were echoed in a number of ways, as in the work of Alkindus, the ninth century Arab philosopher, who aligned the times of the day with particular dispositions. The tetrad could therefore be further embellished, with the first quarter of the day sanguine, second choleric, third melancholic and finally phlegmatic. Astrological allegiances reinforce the idea of four quadrants, so that Jupiter is sanguine, Mars choleric, Saturn is melancholy, and the moon or Venus is phlegmatic. The organs, too, are associated with the points of the humoric tetrad, with the liver sanguine, the gall bladder choleric, the spleen melancholic, and the brain/ lungs phlegmatic.

Melancholy, then, is associated with twilight, autumn, earth, the spleen, coldness and dryness, and the planet Saturn. All of these elements weave in and out of the history of melancholy, appearing in mythology, astrology, medicine, literature and art.The complementary humours and temperaments were sometimes hypothesised as balances, so that the opposite of one might be introduced as a remedy for an excess of another. For melancholy, the introduction of sanguine elements – blood, air and warmth – could counter the darkness. This could also work at an astrological level, as in the appearance of the magic square of Jupiter on the wall behind Albrecht Dürer’s iconic engraving Melencolia I, (1514) – the sign of Jupiter to introduce a sanguine balance to the saturnine melancholy angel.

In this early phase of the development of humoral thinking a key tension arose, as on one hand it was devised as a means of establishing degrees of wellness, but on the other it was a system of types of disposition. As Klibansky, Panofsky and Saxl put it, there were two quite different meanings to the terms sanguine, choleric, phlegmatic and melancholy, as either ‘pathological states or constitutional aptitudes’.9 Melancholy became far more connected with the idea of illness than the other temperaments, and was considered a ‘special problem’.

The blurry boundary between an illness and a mere temperament was a result of the fact that many of the symptoms of ‘melancholia’ were mental, and thus difficult to objectify, unlike something as apparent as a disfigurement or wound. The theory of the humours morphed into psychology and physiognomy, with particular traits or appearances associated with each temperament.

Melancholy was aligned with ‘the lisping, the bald, the stuttering and the hirsute’, and ‘emotional disturbances’ were considered as indicators of ‘mental melancholy’.10 Hippocrates in his Aphorismata, or ‘Aphorisms’, in 400 BC noted, ‘Constant anxiety and depression are signs of melancholy.’ Two centuries later the physician Galen, in an uncharacteristically succinct summation, noted that Hippocrates was ‘right in summing up all melancholy symptoms in the two following: Fear and Depression.’11

The foundations of the ideas on melancholy are fraught with complexity and contradiction, and this signals the beginning of a legacy of richness and debate. We have a love-hate relationship with melancholy, recognising its potential, yet fearing its connotations. What is needed is some kind of guide book, to know how to recognise it, where to find it – akin to the Observer’s Guides, the Blue Guides, or Gavin Pretor-Pinney’s The Cloudspotter’s Guide. Yet, to attempt to write a guide to such an amorphous concept as melancholy is overwhelmingly impossible, such is the breadth and depth of the topic, the disciplinary territories, the disputes, and the extensive creative outpourings. There is a tremendous sense of the infinite, like staring at stars, or at a room full of files, a daunting multitude. The approach is, therefore, to adopt the notion of the ‘constellation’, and to plot various points and co-ordinates, a join-the-dots approach to exploration which roams far and wide, and connects ideas and examples in a way which seeks new combinations and sometimes unexpected juxtapositions.

A Field Guide to Melancholy is therefore in itself a melancholic enterprise: for the writer, and the reader, the very idea of a ‘field guide’ to something so contradictory, so elusive, embodies the impossibility and futility that is central to melancholy’s yearning. Yet, it is this intangible, potent possibility which creates melancholy’s magnetism, recalling Joseph Campbell’s version of the Buddhist advice to “joyfully participate in the sorrows of the world”.12

Notes

1. Victor Hugo, Toilers of the Sea, vol. 3, p.159.

2. Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language, p.458, emphasis mine.

3. This constant shift in the development of concepts is well-illustrated by Umberto Eco (ed) (2004) History of Beauty, New York: Rizzoli, and his recent (2007) On Ugliness, New York: Rizzoli.

4. The term ‘constellation’ is Giorgio Agamben’s, and captures the sense of melancholy’s persistence as a collection of ideas, rather than one simple definition. See Giorgio Agamben, Stanzas:Word and Phantasm in Western Culture, p.19.

5. Julia Kristeva, Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia, p.258.

6. Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky and Fritz Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion and Art, p.79.

7. Slavoj Žižek, Did Somebody say Totalitarianism? Five Interventions on the (Mis)use of a Notion, p.148.

8. In Stanley W Jackson (1986), Melancholia and Depression: From Hippocratic Times to Modern Times, p.9.

9. Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky and Fritz Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion and Art, p.12.

10. ibid, p.15.

11. ibid, p.15, and n.42.

12. A phrase used by Campbell in his lectures, for example on the DVD Joseph Campbell (1998) Sukhavati. Acacia.

__

Excerpted from the introduction to Jacky Bowring’s A Field Guide to Melancholy, Oldcastle Books, 2008.

nite jewel – running out of time (julia holter remix) (2016)

Melancholy AF. Perfect.

the world is ending

jacques derrida & “the science of ghosts” (1983)

Jacques Derrida appearing as himself in Ken McMullen’s Ghost Dance, interviewed by Pascale Ogier in 1983. He’s talking about #PokémonGo from 3:40 ;).

the afterskoolz – akekho ozobona (no one will see) (2016)

Find them on Facebook.