A koeksuster twist.

Category Archives: gender

obnoxious af

angela davis and toni morrison on literacy, libraries and liberation (2010)

Recorded at the New York Public Library on October 27, 2010.

bomba estéreo – soy yo (2016)

“Lo único que importa es lo que esta por dentro,” – you’re the only one whose opinions on you matter.

Written by Liliana Margarita Saumet Avila, Eric Frederic, Joe Spargur, Federico Simon Mejia Ochoa, this catchy anthem is from their 2015 album Amanecer .

Mejía: On this one, we recorded a couple of traditional Colombian instruments live – which is something we like to do on all of our albums. It has a gaita [a folkloric wind instrument of indigenous origin] and a tambor alegre [a percussion instrument of African origin used in cumbia music]. It’s a really fun song and the most Colombian one on the album.

Saumet: The lyrics are about respecting people for who they are and not trying to change them. Sometimes as people we tend to judge others too much. So what if people criticize you? That’s the way you are.

hélène cixous on the term “intellectual” and other problematic words (1992)

bell hooks – understanding patriarchy (2004)

“The crisis facing men is not the crisis of masculinity, it is the crisis of patriarchal masculinity. Until we make this distinction clear, men will continue to fear that any critique of patriarchy represents a threat.”

Patriarchy is the single most life-threatening social disease assaulting the male body and spirit in our nation. Yet most men do not use the word “patriarchy” in everyday life. Most men never think about patriarchy—what it means, how it is created and sustained. Many men in our nation would not be able to spell the word or pronounce it correctly. The word “patriarchy” just is not a part of their normal everyday thought or speech.

Men who have heard and know the word usually associate it with women’s liberation, with feminism, and therefore dismiss it as irrelevant to their own experiences. I have been standing at podiums talking about patriarchy for more than thirty years. It is a word I use daily, and men who hear me use it often ask me what I mean by it.

Nothing discounts the old antifeminist projection of men as all-powerful more than their basic ignorance of a major facet of the political system that shapes and informs male identity and sense of self from birth until death. I often use the phrase “imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy” to describe the interlocking political systems that are the foundation of our nation’s politics. Of these systems the one that we all learn the most about growing up is the system of patriarchy, even if we never know the word, because patriarchal gender roles are assigned to us as children and we are given continual guidance about the ways we can best fulfill these roles.

Patriarchy is a political-social system that insists that males are inherently dominating, superior to everything and everyone deemed weak, especially females, and endowed with the right to dominate and rule over the weak and to maintain that dominance through various forms of psychological terrorism and violence. When my older brother and I were born with a year separating us in age, patriarchy determined how we would each be regarded by our parents. Both our parents believed in patriarchy; they had been taught patriarchal thinking through religion.

At church they had learned that God created man to rule the world and everything in it and that it was the work of women to help men perform these tasks, to obey, and to always assume a subordinate role in relation to a powerful man. They were taught that God was male. These teachings were reinforced in every institution they encountered– schools, courthouses, clubs, sports arenas, as well as churches. Embracing patriarchal thinking, like everyone else around them, they taught it to their children because it seemed like a “natural” way to organize life.

As their daughter I was taught that it was my role to serve, to be weak, to be free from the burden of thinking, to caretake and nurture others. My brother was taught that it was his role to be served; to provide; to be strong; to think, strategize, and plan; and to refuse to caretake or nurture others. I was taught that it was not proper for a female to be violent, that it was “unnatural.” My brother was taught that his value would be determined by his will to do violence (albeit in appropriate settings). He was taught that for a boy, enjoying violence was a good thing (albeit in appropriate settings). He was taught that a boy should not express feelings. I was taught that girls could and should express feelings, or at least some of them.

When I responded with rage at being denied a toy, I was taught as a girl in a patriarchal household that rage was not an appropriate feminine feeling, that it should not only not be expressed but be eradicated. When my brother responded with rage at being denied a toy, he was taught as a boy in a patriarchal household that his ability to express rage was good but that he had to learn the best setting to unleash his hostility. It was not good for him to use his rage to oppose the wishes of his parents, but later, when he grew up, he was taught that rage was permitted and that allowing rage to provoke him to violence would help him protect home and nation.

We lived in farm country, isolated from other people. Our sense of gender roles was learned from our parents, from the ways we saw them behave. My brother and I remember our confusion about gender. In reality I was stronger and more violent than my brother, which we learned quickly was bad. And he was a gentle, peaceful boy, which we learned was really bad. Although we were often confused, we knew one fact for certain: we could not be and act the way we wanted to, doing what we felt like. It was clear to us that our behavior had to follow a predetermined, gendered script. We both learned the word “patriarchy” in our adult life, when we learned that the script that had determined what we should be, the identities we should make, was based on patriarchal values and beliefs about gender.

I was always more interested in challenging patriarchy than my brother was because it was the system that was always leaving me out of things that I wanted to be part of. In our family life of the fifties, marbles were a boy’s game. My brother had inherited his marbles from men in the family; he had a tin box to keep them in. All sizes and shapes, marvelously colored, they were to my eye the most beautiful objects. We played together with them, often with me aggressively clinging to the marble I liked best, refusing to share. When Dad was at work, our stay-at-home mom was quite content to see us playing marbles together. Yet Dad, looking at our play from a patriarchal perspective, was disturbed by what he saw. His daughter, aggressive and competitive, was a better player than his son. His son was passive; the boy did not really seem to care who won and was willing to give over marbles on demand. Dad decided that this play had to end, that both my brother and I needed to learn a lesson about appropriate gender roles.

One evening my brother was given permission by Dad to bring out the tin of marbles. I announced my desire to play and was told by my brother that “girls did not play with marbles,” that it was a boy’s game. This made no sense to my four- or five-year-old mind, and I insisted on my right to play by picking up marbles and shooting them. Dad intervened to tell me to stop. I did not listen. His voice grew louder and louder. Then suddenly he snatched me up, broke a board from our screen door, and began to beat me with it, telling me, “You’re just a little girl. When I tell you to do something, I mean for you to do it.” He beat me and he beat me, wanting me to acknowledge that I understood what I had done. His rage, his violence captured everyone’s attention. Our family sat spellbound, rapt before the pornography of patriarchal violence.

After this beating I was banished—forced to stay alone in the dark. Mama came into the bedroom to soothe the pain, telling me in her soft southern voice, “I tried to warn you. You need to accept that you are just a little girl and girls can’t do what boys do.” In service to patriarchy her task was to reinforce that Dad had done the right thing by, putting me in my place, by restoring the natural social order.

I remember this traumatic event so well because it was a story told again and again within our family. No one cared that the constant retelling might trigger post-traumatic stress; the retelling was necessary to reinforce both the message and the remembered state of absolute powerlessness. The recollection of this brutal whipping of a little-girl daughter by a big strong man, served as more than just a reminder to me of my gendered place, it was a reminder to everyone watching/remembering, to all my siblings, male and female, and to our grown-woman mother that our patriarchal father was the ruler in our household. We were to remember that if we did not obey his rules, we would be punished, punished even unto death. This is the way we were experientially schooled in the art of patriarchy.

There is nothing unique or even exceptional about this experience. Listen to the voices of wounded grown children raised in patriarchal homes and you will hear different versions with the same underlying theme, the use of violence to reinforce our indoctrination and acceptance of patriarchy. In How Can I Get Through to You? family therapist Terrence Real tells how his sons were initiated into patriarchal thinking even as their parents worked to create a loving home in which antipatriarchal values prevailed. He tells of how his young son Alexander enjoyed dressing as Barbie until boys playing with his older brother witnessed his Barbie persona and let him know by their gaze and their shocked, disapproving silence that his behavior was unacceptable:

Without a shred of malevolence, the stare my son received transmitted a message. You are not to do this. And the medium that message was broadcast in was a potent emotion: shame. At three, Alexander was learning the rules. A ten second wordless transaction was powerful enough to dissuade my son from that instant forward from what had been a favorite activity. I call such moments of induction the “normal traumatization” of boys.

To indoctrinate boys into the rules of patriarchy, we force them to feel pain and to deny their feelings.

My stories took place in the fifties; the stories Real tells are recent. They all underscore the tyranny of patriarchal thinking, the power of patriarchal culture to hold us captive. Real is one of the most enlightened thinkers on the subject of patriarchal masculinity in our nation, and yet he lets readers know that he is not able to keep his boys out of patriarchy’s reach. They suffer its assaults, as do all boys and girls, to a greater or lesser degree. No doubt by creating a loving home that is not patriarchal, Real at least offers his boys a choice: they can choose to be themselves or they can choose conformity with patriarchal roles. Real uses the phrase “psychological patriarchy” to describe the patriarchal thinking common to females and males. Despite the contemporary visionary feminist thinking that makes clear that a patriarchal thinker need not be a male, most folks continue to see men as the problem of patriarchy. This is simply not the case. Women can be as wedded to patriarchal thinking and action as men.

Psychotherapist John Bradshaw’s clear sighted definition of patriarchy in Creating Love is a useful one: “The dictionary defines ‘patriarchy’ as a ‘social organization marked by the supremacy of the father in the clan or family in both domestic and religious functions’.” Patriarchy is characterized by male domination and power. He states further that “patriarchal rules still govern most of the world’s religious, school systems, and family systems.” Describing the most damaging of these rules, Bradshaw lists “blind obedience—the foundation upon which patriarchy stands; the repression of all emotions except fear; the destruction of individual willpower; and the repression of thinking whenever it departs from the authority figure’s way of thinking.” Patriarchal thinking shapes the values of our culture. We are socialized into this system, females as well as males. Most of us learned patriarchal attitudes in our family of origin, and they were usually taught to us by our mothers. These attitudes were reinforced in schools and religious institutions.

The contemporary presence of female-headed households has led many people to assume that children in these households are not learning patriarchal values because no male is present. They assume that men are the sole teachers of patriarchal thinking. Yet many female-headed households endorse and promote patriarchal thinking with far greater passion than two-parent households. Because they do not have an experiential reality to challenge false fantasies of gender roles, women in such households are far more likely to idealize the patriarchal male role and patriarchal men than are women who live with patriarchal men every day. We need to highlight the role women play in perpetuating and sustaining patriarchal culture so that we will recognize patriarchy as a system women and men support equally, even if men receive more rewards from that system. Dismantling and changing patriarchal culture is work that men and women must do together.

Clearly we cannot dismantle a system as long as we engage in collective denial about its impact on our lives. Patriarchy requires male dominance by any means necessary, hence it supports, promotes, and condones sexist violence. We hear the most about sexist violence in public discourses about rape and abuse by domestic partners. But the most common forms of patriarchal violence are those that take place in the home between patriarchal parents and children. The point of such violence is usually to reinforce a dominator model, in which the authority figure is deemed ruler over those without power and given the right to maintain that rule through practices of subjugation, subordination, and submission.

Keeping males and females from telling the truth about what happens to them in families is one way patriarchal culture is maintained. A great majority of individuals enforce an unspoken rule in the culture as a whole that demands we keep the secrets of patriarchy, thereby protecting the rule of the father. This rule of silence is upheld when the culture refuses everyone easy access even to the word “patriarchy.” Most children do not learn what to call this system of institutionalized gender roles, so rarely do we name it in everyday speech. This silence promotes denial. And how can we organize to challenge and change a system that cannot be named?

It is no accident that feminists began to use the word “patriarchy” to replace the more commonly used “male chauvinism” and “sexism.” These courageous voices wanted men and women to become more aware of the way patriarchy affects us all. In popular culture the word itself was hardly used during the heyday of contemporary feminism. Antimale activists were no more eager than their sexist male counterparts to emphasize the system of patriarchy and the way it works. For to do so would have automatically exposed the notion that men were all-powerful and women powerless, that all men were oppressive and women always and only victims. By placing the blame for the perpetuation of sexism solely on men, these women could maintain their own allegiance to patriarchy, their own lust for power. They masked their longing to be dominators by taking on the mantle of victimhood.

Like many visionary radical feminists I challenged the misguided notion, put forward by women who were simply fed up with male exploitation and oppression, that men were “the enemy.” As early as 1984 I included a chapter with the title “Men: Comrades in Struggle” in my book Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center urging advocates of feminist politics to challenge any rhetoric which placed the sole blame for perpetuating patriarchy and male domination onto men:

Separatist ideology encourages women to ignore the negative impact of sexism on male personhood. It stresses polarization between the sexes. According to Joy Justice, separatists believe that there are “two basic perspectives” on the issue of naming the victims of sexism: “There is the perspective that men oppress women. And there is the perspective that people are people, and we are all hurt by rigid sex roles.”…Both perspectives accurately describe our predicament. Men do oppress women. People are hurt by rigid sexist role patterns, These two realities coexist. Male oppression of women cannot be excused by the recognition that there are ways men are hurt by rigid sexist roles. Feminist activists should acknowledge that hurt, and work to change it—it exists. It does not erase or lessen male responsibility for supporting and perpetuating their power under patriarchy to exploit and oppress women in a manner far more grievous than the serious psychological stress and emotional pain caused by male conformity to rigid sexist role patterns.

Throughout this essay I stressed that feminist advocates collude in the pain of men wounded by patriarchy when they falsely represent men as always and only powerful, as always and only gaining privileges from their blind obedience to patriarchy. I emphasized that patriarchal ideology brainwashes men to believe that their domination of women is beneficial when it is not:

Often feminist activists affirm this logic when we should be constantly naming these acts as expressions of perverted power relations, general lack of control of one’s actions, emotional powerlessness, extreme irrationality, and in many cases, outright insanity. Passive male absorption of sexist ideology enables men to falsely interpret this disturbed behavior positively. As long as men are brainwashed to equate violent domination and abuse of women with privilege, they will have no understanding of the damage done to themselves or to others, and no motivation to change.

Patriarchy demands of men that they become and remain emotional cripples. Since it is a system that denies men full access to their freedom of will, it is difficult for any man of any class to rebel against patriarchy, to be disloyal to the patriarchal parent, be that parent female or male.

The man who has been my primary bond for more than twelve years was traumatized by the patriarchal dynamics in his family of origin. When I met him he was in his twenties. While his formative years had been spent in the company of a violent, alcoholic dad, his circumstances changed when he was twelve and he began to live alone with his mother.

In the early years of our relationship he talked openly about his hostility and rage toward his abusing dad. He was not interested in forgiving him or understanding the circumstances that had shaped and influenced his dad’s life, either in his childhood or in his working life as a military man. In the early years of our relationship he was extremely critical of male domination of women and children. Although he did not use the word “patriarchy,” he understood its meaning and he opposed it. His gentle, quiet manner often led folks to ignore him, counting him among the weak and the powerless. By the age of thirty he began to assume a more macho persona, embracing the dominator model that he had once critiqued. Donning the mantle of patriarch, he gained greater respect and visibility. More women were drawn to him. He was noticed more in public spheres. His criticism of male domination ceased. And indeed he begin to mouth patriarchal rhetoric, saying the kind of sexist stuff that would have appalled him in the past.

These changes in his thinking and behavior were triggered by his desire to be accepted and affirmed in a patriarchal workplace and rationalized by his desire to get ahead. His story is not unusual. Boys brutalized and victimized by patriarchy more often than not become patriarchal, embodying the abusive patriarchal masculinity that they once clearly recognized as evil. Few men brutally abused as boys in the name of patriarchal maleness courageously resist the brainwashing and remain true to themselves. Most males conform to patriarchy in one way or another.

Indeed, radical feminist critique of patriarchy has practically been silenced in our culture. It has become a subcultural discourse available only to well-educated elites. Even in those circles, using the word “patriarchy” is regarded as passé. Often in my lectures when I use the phrase “imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy” to describe our nation’s political system, audiences laugh. No one has ever explained why accurately naming this system is funny. The laughter is itself a weapon of patriarchal terrorism. It functions as a disclaimer, discounting the significance of what is being named. It suggests that the words themselves are problematic and not the system they describe. I interpret this laughter as the audience’s way of showing discomfort with being asked to ally themselves with an anti-patriarchal disobedient critique. This laughter reminds me that if I dare to challenge patriarchy openly, I risk not being taken seriously.

Citizens in this nation fear challenging patriarchy even as they lack overt awareness that they are fearful, so deeply embedded in our collective unconscious are the rules of patriarchy. I often tell audiences that if we were to go door-to-door asking if we should end male violence against women, most people would give their unequivocal support. Then if you told them we can only stop male violence against women by ending male domination, by eradicating patriarchy, they would begin to hesitate, to change their position. Despite the many gains of contemporary feminist movement—greater equality for women in the workforce, more tolerance for the relinquishing of rigid gender roles—patriarchy as a system remains intact, and many people continue to believe that it is needed if humans are to survive as a species. This belief seems ironic, given that patriarchal methods of organizing nations, especially the insistence on violence as a means of social control, has actually led to the slaughter of millions of people on the planet.

Until we can collectively acknowledge the damage patriarchy causes and the suffering it creates, we cannot address male pain. We cannot demand for men the right to be whole, to be givers and sustainers of life. Obviously some patriarchal men are reliable and even benevolent caretakers and providers, but still they are imprisoned by a system that undermines their mental health.

Patriarchy promotes insanity. It is at the root of the psychological ills troubling men in our nation. Nevertheless there is no mass concern for the plight of men. In Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man, Susan Faludi includes very little discussion of patriarchy:

Ask feminists to diagnose men’s problems and you will often get a very clear explanation: men are in crisis because women are properly challenging male dominance. Women are asking men to share the public reins and men can’t bear it. Ask antifeminists and you will get a diagnosis that is, in one respect, similar. Men are troubled, many conservative pundits say, because women have gone far beyond their demands for equal treatment and are now trying to take power and control away from men…The underlying message: men cannot be men, only eunuchs, if they are not in control. Both the feminist and antifeminist views are rooted in a peculiarly modern American perception that to be a man means to be at the controls and at all times to feel yourself in control.

Faludi never interrogates the notion of control. She never considers that the notion that men were somehow in control, in power, and satisfied with their lives before contemporary feminist movement is false.

Patriarchy as a system has denied males access to full emotional well-being, which is not the same as feeling rewarded, successful, or powerful because of one’s capacity to assert control over others. To truly address male pain and male crisis we must as a nation be willing to expose the harsh reality that patriarchy has damaged men in the past and continues to damage them in the present. If patriarchy were truly rewarding to men, the violence and addiction in family life that is so all-pervasive would not exist. This violence was not created by feminism. If patriarchy were rewarding, the overwhelming dissatisfaction most men feel in their work lives—a dissatisfaction extensively documented in the work of Studs Terkel and echoed in Faludi’s treatise—would not exist.

In many ways Stiffed was yet another betrayal of American men because Faludi spends so much time trying not to challenge patriarchy that she fails to highlight the necessity of ending patriarchy if we are to liberate men. Rather she writes:

Instead of wondering why men resist women’s struggle for a freer and healthier life, I began to wonder why men refrain from engaging in their own struggle. Why, despite a crescendo of random tantrums, have they offered no methodical, reasoned response to their predicament: Given the untenable and insulting nature of the demands placed on men to prove themselves in our culture, why don’t men revolt?…Why haven’t men responded to the series of betrayals in their own lives—to the failures of their fathers to make good on their promises–with something coequal to feminism?

Note that Faludi does not dare risk either the ire of feminist females by suggesting that men can find salvation in feminist movement or rejection by potential male readers who are solidly antifeminist by suggesting that they have something to gain from engaging feminism. So far in our nation visionary feminist movement is the only struggle for justice that emphasizes the need to end patriarchy. No mass body of women has challenged patriarchy and neither has any group of men come together to lead the struggle. The crisis facing men is not the crisis of masculinity, it is the crisis of patriarchal masculinity. Until we make this distinction clear, men will continue to fear that any critique of patriarchy represents a threat. Distinguishing political patriarchy, which he sees as largely committed to ending sexism, therapist Terrence Real makes clear that the patriarchy damaging us all is embedded in our psyches: Psychological patriarchy is the dynamic between those qualities deemed “masculine” and “feminine” in which half of our human traits are exalted while the other half is devalued. Both men and women participate in this tortured value system.

Psychological patriarchy is a “dance of contempt,” a perverse form of connection that replaces true intimacy with complex, covert layers of dominance and submission, collusion and manipulation. It is the unacknowledged paradigm of relationships that has suffused Western civilization generation after generation, deforming both sexes, and destroying the passionate bond between them.

By highlighting psychological patriarchy, we see that everyone is implicated and we are freed from the misperception that men are the enemy. To end patriarchy we must challenge both its psychological and its concrete manifestations in daily life. There are folks who are able to critique patriarchy but unable to act in an antipatriarchal manner.

To end male pain, to respond effectively to male crisis, we have to name the problem. We have to both acknowledge that the problem is patriarchy and work to end patriarchy. Terrence Real offers this valuable insight:

“The reclamation of wholeness is a process even more fraught for men than it has been for women, more difficult and more profoundly threatening to the culture at large.”

If men are to reclaim the essential goodness of male being, if they are to regain the space of openheartedness and emotional expressiveness that is the foundation of well-being, we must envision alternatives to patriarchal masculinity. We must all change.

___

This is an excerpt from The Will To Change by bell hooks (chapter 2).

bell hooks is an American social activist, feminist and author. She was born on September 25, 1952. bell hooks is the nom de plume for Gloria Jean Watkins. bell hooks examines the multiple networks that connect gender, race, and class. She examines systematic oppression with the goal of a liberatory politics. She also writes on the topics of mass media, art, and history. bell hooks is a prolific writer, having composed a plethora of articles for mainstream and scholarly publications. bell hooks has written and published dozens of books. At Yale University, bell hooks was a Professor of African and African-American Studies and English. At Oberlin College, she was an Associate Professor of Women‚’s Studies and American Literature. At the City College of New York, bell hooks also held the position of Distinguished Lecturer of English Literature. bell hooks has been awarded The American Book Awards/Before Columbus Foundation Award, The Writer’s Award from Lila Wallace-Reader’s Digest Fund, and The Bank Street College Children’s Book of the Year. She has also been ranked as one of the most influential American thinkers by Publisher’s Weekly and The Atlantic monthly.

This work is licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

tim hjersted on what we are here for

I have made a promise to this world that I will carry with me to my last days. It is my vow to lessen the suffering of the world while I am here – it is to ensure that every toxic legacy that I inherited from our culture ends with me – and, ideally, ends with all of us, in our lifetime. The task may be impossible, but I have to help. I have to do it because my true nature wants me to. When I do this work, my heart sings. My inner self rejoices. That is because your happiness is my happiness. Doing the work connects me with what is really true. We are all connected. We are all in relationship.

Focusing on media activism, it is quite easy to get swept up in a thousand different messages, leaving me sometimes feeling like I’ve gotten off track with my core message and purpose. What am I doing here? Why am I here?

The answer is in an old Sufi song I learned as a child, “What are we here for? To love, serve and remember.”

To love, serve and remember.

Remember what?

That we are all family.

That you are because I am.

That what is sacred in me is sacred in you. And that sacredness pervades the cosmos, if we choose.*

Reverence and awe for the world is our choice to make. We can see that beauty, and live that life, or we can choose not to see it, and live without that beauty.

Look at your lover this way today. See the sacred in her. See the sacred in him. When you see it in them, see it in your family and your friends. Then, start looking for it in people you see at the grocery store and on the street. Then see it in all of the animal creatures in your life. See it in the trees and plants that grow outside your house. See life in everything, truly be present to its nature and vibrational energy.

Each person in the world is family – caught with us amid the “splendour and travail of the earth.”

When we see the sacred in every person, we can see that those who cause others to suffer are also suffering and have been deeply wounded by this culture since they were born. Every child is born with love in their hearts. The child does not know that we are not all family until they are taught so. This is how we forget.

Our culture teaches us to forget. Our culture teaches us who to love and who not to love. It is a very small circle of people. But that circle is growing bigger for more and more people each day.

More and more people are remembering that our family is life itself.

That is the core message I am trying to spread with my activism.

From this revolution of the heart flowers every other revolution. Sexism, racism, environmental destruction, poverty and war are not possible when true love is there. True love dissolves illusion. True love shatters prejudice and malice. True love liberates both the child and the adult from centuries of our inherited suffering. It is the revolution we need most desperately to save every 5 year old child from the suffering they will inherit if we do not vow to ensure that every toxic cultural legacy of our culture ends with us.

*I define sacred as something having intrinsic worth and value, so for me the word connects with me on both a secular and spiritual level. In a scientific sense that value may be entirely subjective, but I’m okay with that. For me, it’s a choice to see the sacred in life. I can choose to see that beauty, or not see it.

___

Tim Hjersted is the director and co-founder of Films For Action. 16 August 2016.

This work is licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

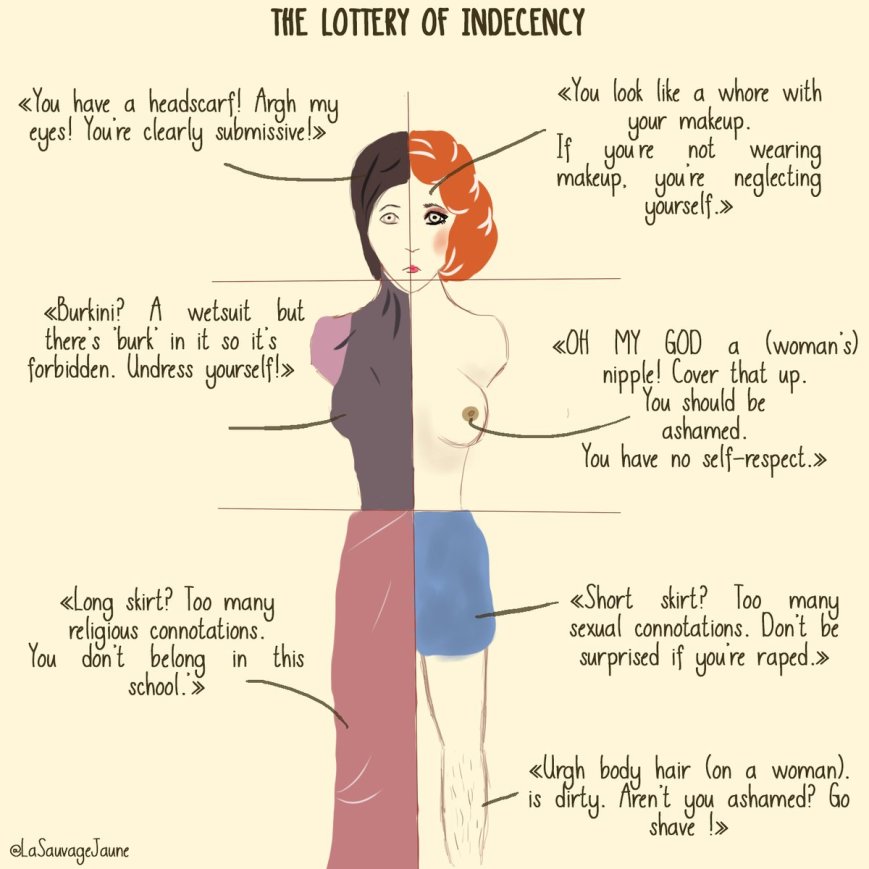

the lottery of indecency (2016)

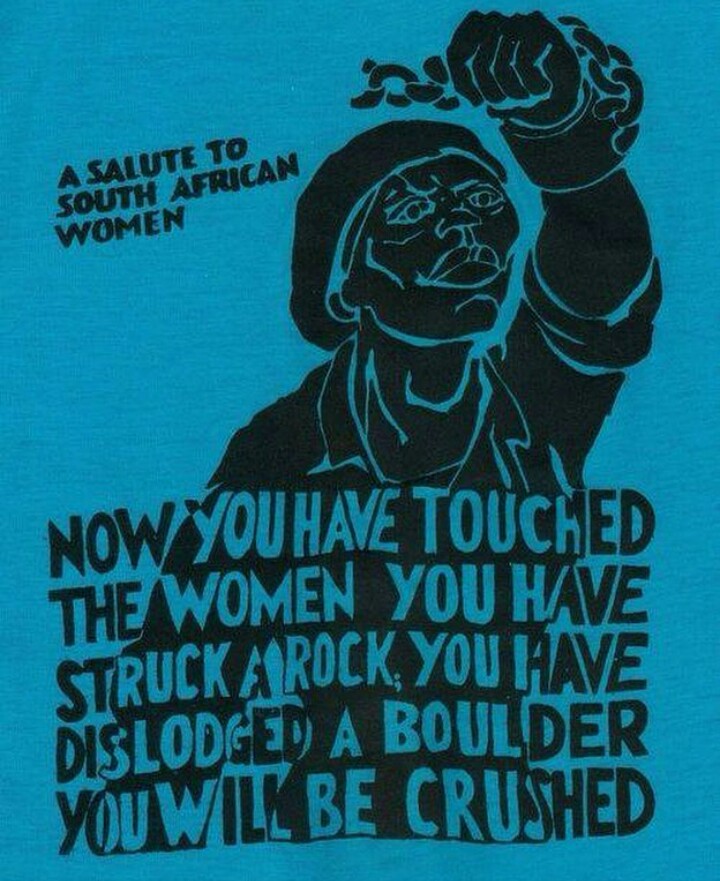

9 august

On set at Muti Films tonight.

maya deren – ritual in transfigured time (1946)

Originally a silent film, this soundtrack was added by Nikos Kokolakis in 2015 – turn the sound off if you prefer.

About her fourth complete film, Ritual in Transfigured Time (1946), Maya Deren writes: “A ritual is an action that seeks the realisation of its purpose through the exercise of form… In this sense ritual is art; and even historically, all art derives from ritual. In ritual, the form is the meaning. More specifically, the quality of movement is not merely a decorative factor; it is the meaning itself of the movement. In this sense, this film is dance […] It’s an inversion towards life, the passage from sterile winter into fertile spring; mortality into immortality; the child-son into the man-father; or, as in this film, the widow into the bride”.

– Maya Deren: Chamber Films, program notes for a presentation, 1960

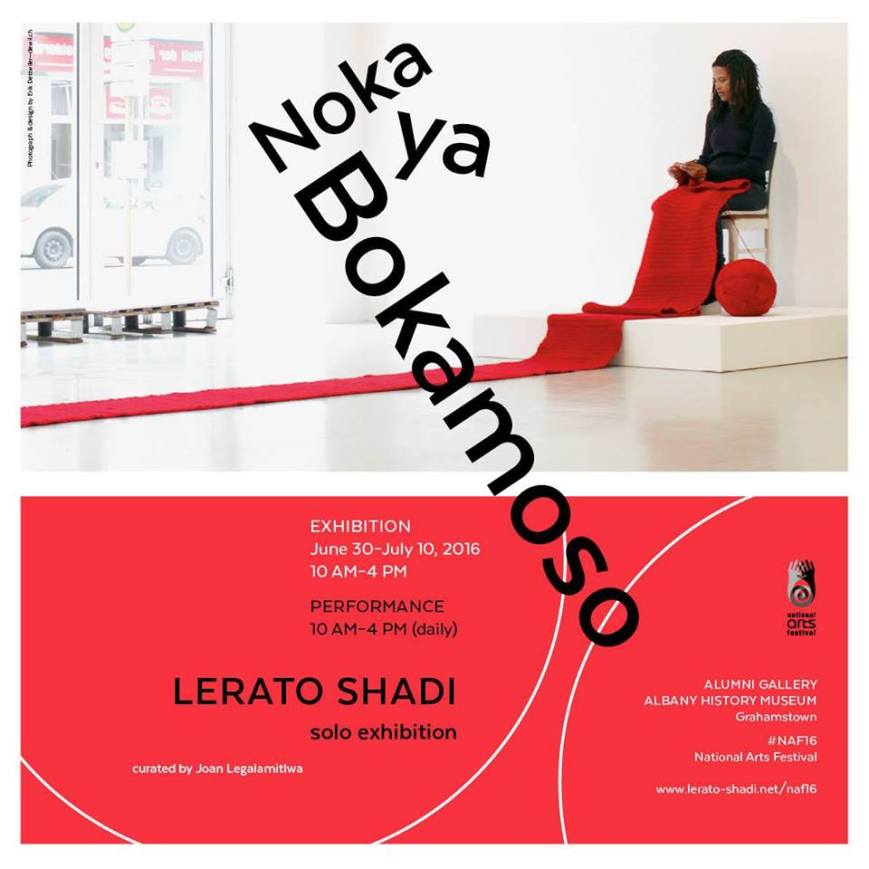

opening tomorrow: lerato shadi – noka ya bokamoso

NOKA YA BOKAMOSO: A SOLO EXHIBITION BY LERATO SHADI

2016 National Arts Festival – Grahamstown

Alumni Gallery, Albany History Museum

30 June – 10 July

Lerato Shadi invites you to her latest solo exhibition and debut National Arts Festival appearance, Noka Ya Bokamoso. This exhibition by the Mahikeng born, Berlin based video and performance artist is one of the six visual art showcases chosen for the main programme.

The exhibition features four of Shadi’s latest works; two performative installations Makhubu and Mosako Wa Nako as well as two video works Sugar & Salt and Untitled.

Curator, Joan Legalamitlwa says,

“The works on the show were purposefully selected as they weave together history as told by and through the Black female body, in its truest and sincerest form, as it should be. Noka Ya Bokamoso is about the Black subject being in control of its own narrative and also about encouraging the visitors to do some introspection when it comes to matters of identity and representation.”

Makhubu is a work performed in the days preceding the festival, executed in absence of an audience. This performance involves Shadi arduously writing in concentric circles with a red pencil, then erasing the writing, leaving traces of the text on the wall and red remnants of the rubber eraser on the floor. This work looks at the historical erasure of the Black subject within the context of Grahamstown’s problematic history as well as historic erasure in the national narrative and how that has impacted on the kinds of stories that we currently tell. The absence of an audience becomes a corporeal metaphor, emphasising the ways in which South Africans, continue to construct a sense of nationhood unaware of significant violent acts that have shaped them.

For Mosako Wa Nako, Shadi will be seated one end of the gallery space for an uninterrupted six hours a day, over the eleven days of the Festival, crocheting what looks like be a red woollen carpet. Sugar & Salt, a video work featuring Shadi and her mother consuming a mineral in the form of salt and a carbohydrate in the form of sugar, makes references to the complexities and intricacies of mother-daughter relationships.

Untitled, Shadi’s latest video work, having its world premiere at the National Arts Festival, will be shot on location in her home village of Lotlhakane, in June 2016. The work consists of a two channel video work conceptualised in three parts: the first deals with the utmost extremes of individual resistance; the second deals with how Shadi experiences the impact of colonial language; the final part is an allegory of resistance.

Shadi’s work explores problematic assumptions projected onto the Black female body and how performance, video and installation create a space for artists to engage with those preconceived notions, making the body both visible and invisible. Using time, repetitive actions as well as stillness, she questions, ‘How does one create oneself?’ rather than allowing others or history to shape one’s person.

The key aim of Noka Ya Bokamoso is to re-center Shadi’s works to its primary audience – the South African audience. Shadi has practiced and exhibited in New York, Bern, Dakar, Moscow and Scotland and now seeks to utilise her work to foster and encourage dialogue around questions of historical knowledge production and its inclusion and exclusion of certain subjects. Her ultimate goal is that she, along with her audiences, will be encouraged not only to consume, but consciously engage in the processes of unearthing subsumed histories and producing critical knowledge.

Lerato Shadi lives and works in Berlin. She completed a BFA in Fine Art from the University of Johannesburg. She was included in The Generational: ‘Younger Than Jesus’ artists directory published by the New Museum, New York. In 2010 she was awarded a Pro Helvetia residency in Bern. In the same year she had her solo exhibition Mosako Wa Seipone at Goethe on Main in Johannesburg. From 2010 to 2012 she was a member of the Bag Factory artist studios in Johannesburg. In 2012 her work was featured at the Dak’art Biennale in Dakar, Senegal and in the III Moscow International Biennale. She is a fellow of Sommerakademie 2013 (Zentrum Paul Klee) and completed in the same year a residency program by invitation of INIVA at Hospitalfield (supported by ROSL). In 2014 she was awarded with the mart stam studio grant. She is currently completing her MFA at the Kunsthochschule Berlin Weissensee.

Noka Ya Bokamoso is made possible through the generous support of the National Arts Festival.

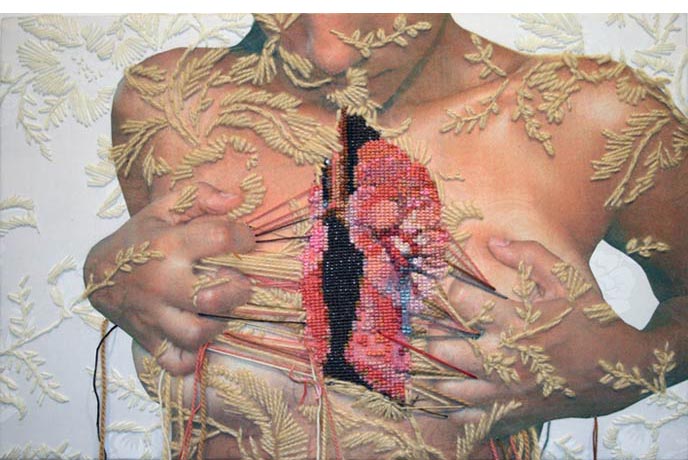

katie collins – woven into the fabric of the text (2016)

The following is excerpted from a feature essay on the LSE blog by Katie Collins, entitled “Woven into the Fabric of the Text: Subversive Material Metaphors in Academic Writing”. Collins proposes that we shift our thinking about academic writing from building metaphors – the language of frameworks, foundations and buttresses – to stitching, sewing and piecing. Needlecraft metaphors offer another way of thinking about the creative and generative practice of academic writing as decentred, able to accommodate multiple sources and with greater space for the feminine voice.

__

[W]hy do I regard switching from a metaphor of building to one of stitching as a subversive act? For several reasons. Throughout history, needlework has been a marker of femininity in its various iterations, a means to inculcate it, and something to sneer at as a way of shoring up women’s supposed inferiority. Theodore Roethke described women’s poetry as ‘the embroidering of trivial themes […] running between the boudoir and the alter, stamping a tiny foot against God…’ (165), for example. Women’s naturally nimble fingers were to be occupied; we were to be kept out of the way and out of trouble, shut in the top room of a circular tower and thus prevented from engaging in the masculine pursuits of politics, thinking, reading and writing and making Art (for a fascinating discussion on women, folk art and cultural femicide, I recommend this post by Dr Lucy Allen). The frills and fripperies our needles produced were ample evidence, should anyone require it, that we were frivolous creatures entirely unsuited to public life. Or so the story was. So using needlework metaphors in my academic writing blows a resonant raspberry to that notion, for one thing. But the subversion here is not as straightforward as reclamation, of presenting something usually disparaged as having value after all. Femininity and its inculcation is a displeasingly twisted yarn of benevolence and belittlement. The trick is to unpick the knots without snapping the thread and unravelling the beautiful work, to value that which has been constructed as feminine while at the same time escaping its constricting net.

Imagining academic writing as piecing fragments is one way of recognising that it can integrate all sorts of sources but, more significantly, piecing is also a decentred activity. When quilting, one can plan, cut and stitch many individual squares whenever there is a moment spare, before bringing them together to form the overall pattern, which is flat and in aesthetic terms may have no centre or many centres, and no predetermined start or end. This holds true both for the practice of quilting and how we might think differently about academic writing, with each contribution not a brick in a structured wall but a square ready to stitch onto other squares to make something expected or unexpected, the goal depth and intensity rather than progress (see Mara Witzling). There is sedition here in several senses. This way of imagining how writing works is not individualistic or competitive. Each voice is a thread, and only when they are woven together do they form a whole, as Ann Hamilton’s tapestries represent social collaboration and interconnectedness; many voices not one, cut from the same cloth or different.

But acknowledging that one might have to fit the work of writing around other things, a problem that has occupied me from the moment I became a mother, is a particularly rebellious act, I think. As Adrienne Rich expresses in the poem ‘Transcendental Etude’:

Vision begins to happen in such a life

as if a woman quietly walked away

from the argument and jargon in a room

and sitting down in the kitchen, began turning in her lap

bits of yarn, calico and velvet scraps,

laying them out absently on the scrubbed boards

in the lamplight, with small rainbow-colored shells

sent in cotton-wool from somewhere far away,

and skeins of milkweed from the nearest meadow –

original domestic silk, the finest findings.

This way of imagining academic writing as something that is part of life, rather than something apart, challenges the view of the scholar as the extraordinary, solitary genius who sits alone in his study day after day while the minutiae of clothing and food is organised for him, around him, despite him. But with metaphors that emphasise the piecing of fragments, both everyday and exceptional, we recognise a way of working in which every fragment that can be pieced together into a square is ‘the preservation of a woman’s voice’.

Read the whole of this great essay by Katie Collins HERE.

adrienne rich – diving into the wreck

First having read the book of myths,

First having read the book of myths,

and loaded the camera,

and checked the edge of the knife-blade,

I put on

the body-armor of black rubber

the absurd flippers

the grave and awkward mask.

I am having to do this

not like Cousteau with his

assiduous team

aboard the sun-flooded schooner

but here alone.

There is a ladder.

The ladder is always there

hanging innocently

close to the side of the schooner.

We know what it is for,

we who have used it.

Otherwise

it is a piece of maritime floss

some sundry equipment.

I go down.

Rung after rung and still

the oxygen immerses me

the blue light

the clear atoms

of our human air.

I go down.

My flippers cripple me,

I crawl like an insect down the ladder

and there is no one

to tell me when the ocean

will begin.

First the air is blue and then

it is bluer and then green and then

black I am blacking out and yet

my mask is powerful

it pumps my blood with power

the sea is another story

the sea is not a question of power

I have to learn alone

to turn my body without force

in the deep element.

And now: it is easy to forget

what I came for

among so many who have always

lived here

swaying their crenellated fans

between the reefs

and besides

you breathe differently down here.

I came to explore the wreck.

The words are purposes.

The words are maps.

I came to see the damage that was done

and the treasures that prevail.

I stroke the beam of my lamp

slowly along the flank

of something more permanent

than fish or weed

the thing I came for:

the wreck and not the story of the wreck

the thing itself and not the myth

the drowned face always staring

toward the sun

the evidence of damage

worn by salt and sway into this threadbare beauty

the ribs of the disaster

curving their assertion

among the tentative haunters.

This is the place.

And I am here, the mermaid whose dark hair

streams black, the merman in his armored body.

We circle silently

about the wreck

we dive into the hold.

I am she: I am he

whose drowned face sleeps with open eyes

whose breasts still bear the stress

whose silver, copper, vermeil cargo lies

obscurely inside barrels

half-wedged and left to rot

we are the half-destroyed instruments

that once held to a course

the water-eaten log

the fouled compass

We are, I am, you are

by cowardice or courage

the one who find our way

back to this scene

carrying a knife, a camera

a book of myths

in which

our names do not appear.

__

From Diving into the Wreck: Poems 1971-1972. W. W. Norton & Company, 2013

i’m glad i never (demo – 2015)

I recorded this 1971 Lee Hazlewood song last year in Copenhagen on New Year’s Eve with Jim Neversink. I love how a song’s original sense can be radically subverted when a person in a different subject position sings.

grimm versus gira (2008 – 2016)

I share this in solidarity with Larkin Grimm, and my niece Juliette, and every other woman who has been exploited or violated through unequal power relationships during artistic collaboration. Speak your truth. Don’t shut up. Make them squirm. Let them burn.

—

Yesterday, singer/songwriter Larkin Grimm claimed that Swans frontman Michael Gira raped her in spring 2008, when she was recording her album Parplar for Gira’s Young God label. In a Facebook post yesterday, she said she confronted Gira and he then dropped her from his label. Gira called Grimm’s accusations “a slanderous lie” on his personal Facebook page. In an official statement through his publicist, Gira has acknowledged the spring 2008 night in question, but calls the incident “an awkward mistake.” Read his full statement below. Update (2/27, 9:40 a.m.): Grimm sent us a statement in response to Gira’s comments, which she calls “an admission of guilt.” Read it below.

Michael Gira:

Eight years ago, while I was still married to my first wife, Larkin Grimm and I headed towards a consensual romantic moment that fortunately was not consummated. As she wrote in her recent social media postings about that night, I said to her, “this doesn’t feel right,” and abruptly but completely our only intimate encounter ended. It was an awkward mistake.

Larkin may regret, as I certainly do, that the ill-advised tryst went even that far, but now, as then, I hold her in high esteem for her music and her courage as an artist.

I long ago apologized to my wife and family and told them the truth about this incident. My hope is that Larkin finds peace with the demons that have been darkening her soul since long before she and I ever met.

Larkin Grimm:

This is a perfect example of why we need to have education about consent. In a gentlemanly move he admits the act happened but cannot conceive of himself as a rapist. Thank you Michael Gira for your honesty. This is your truth as you remember it. Unfortunately, this was still rape. I said no to you many times before that day, begged you not to interfere with me sexually, even made it a part of a verbal agreement we had when I signed a contract with you. I asked you to promise that you would never have sex with me. You assured me that I could trust you. That is about as clear a NO as I could ever cry. I asked for this because I had had other experiences in my music career and I KNEW.

That night I was far too intoxicated to give you consent for any sexual act. The psychological effects of this betrayal were devastating. Even worse, when I finally confronted you about what you had done, you terminated my relationship with Young God Records, damaging my career and leading people to believe there was something wrong with me or my music.

In the end, this is about business. Art is my career. I have worked long and hard for this career, making incredible sacrifices along the way to continue to make music. The fact that a man in power can throw a woman’s life and work away like they are garbage, simply because she won’t sleep with him, is an immoral injustice that happens to many, many women in music. I won’t stand for it and neither should you.

The “Demons darkening my soul” are the men like you who interfere with my ability to do my work as a musician. This is a job I am good at. All I want is to be left in peace while I am working.

From Pitchfork.

larkin grimm interview (2014)

alexis pauline gumbs – pulse (for the 50 and beyond)

A poem for those who died, shot in Pulse nightclub in Orlando this weekend past.

i was going to see you

i was going to dance

in the same place with you someday

i was going to pretend not to notice

how you and your friends smiled

when you saw me and my partner

trying to cumbia to bachata

but i was going to feel more free anyway

because you were smiling

and we were together

and you had your stomach out

and you felt beautiful in your sweat

i was going to smile when i walked by

i was going to hug you the first time

a friend of a friend introduced us

i was going to compliment your shoes

instead of writing you a love poem

i was going to smile every time i saw you

and struggle to remember your name

we were going to sing together

we were going to belt out Selena

i was going to mispronounce everything

except for amor

and ay ay ay

i was going to covet your confidence and your bracelet

i was going to be grateful for the sight of you

i was going scream YES!!! at nothing in particular

at everything especially

meaning you

meaning you beyond who i knew you to be

i was going to see you in hallways

and be too shy to say hello

you were going to come to the workshop

you were going to sign up for the workshop and not come

you were going to translate the webinar

even though my politics seemed out there

we were going to sign up for creating change the same day

and be reluctant about it for completely different reasons

we were going to watch the keynotes

and laugh at completely different times

i was going to hold your hand in a big activity

about the intimacy of strangers

about the strangeness of needing prayer

we were going to get the same automated voice message

when we complained that it was not what it should have been

we were going to be standing in the same line

for various overpriced drinks

during a shift change

i was going to breathe loudly so you would notice me

you were going to compliment my hair

it isn’t fair

because we were going to work

to beyonce and rihanna

and the rihanna’s and beyonce’s to come

and the beyonce’s and rihanna’s after that

we were going to not drink enough water

and stay out later than our immune systems could handle

we were going to sit in traffic in each others blindspots

listening to top 40 songs that trigger queer memories

just outside the scope of marketing predictions

we were going to get old and i was going to wonder

about the hint of a tattoo i could see under your sleeve

i was going to blink and just miss

the fought-for laughter lines around your liner-loved eyes

i was going to go out for my birthday

but i didn’t

and you did

we were going to be elders

just because we were still around

and i was going to listen to you on a panel

we didn’t feel qualified for

and hear you talk about your guilt

for still being alive

when so many of your friends were taken

by suicide

by AIDS

by racist police

and jealous ex-lovers

and poverty

and no access to healthcare

and how you had a stable job

you suffered at until the weekend

how you avoided the drama

and only went to the club at pride

and so here you were with no one to dance with anymore

i was going to see you and forget you

and only remember you in my hips

and how my smile came easier than clenching my teeth eventually

and how i finally learned whatever it is i still haven’t learned yet

i was going to hear you laugh and not know why

and not care

our ancestors fought for a future

and we were both going to be there

until we weren’t

and i don’t know if it would hurt more

to lose you later after knowing you

i don’t know if it would hurt more

to know you died on your own day

by your own hands

or any of the other systems

that stalk you and me and ours forever

i only know the pain that i am having

and that you are not here to share it

you are not here to bear it

you were going to pass me a candle at the next vigil

but now i am pulse

and now you

are flame.

helen mirren in herostratus (1967)

A scene from the movie Herostratus (1967), directed by experimental filmmaker Don Levy.

The plot of Herostratus is deceptively simple: A young poet, Max (Michael Gothard), is sick of being poor, unemployed and feeling inadequate and unnoticed and trapped by society. After a few setbacks early in the film, particularly when it comes to paying the rent to a landlady he can no longer avoid, Max decides to commit suicide by jumping off a tall building. But Max decides to make a point of his death instead, and enlists the help of Farson (Peter Stephens), a successful public relations ad man, who helps him turn his suicide, conceived as a sacrificial act of protest against modern society, into a media circus.

Farson does not actually believe Max will go through with the suicide, and decides to let Max spend time at his studio, and its there that Max falls in love with Farson’s assistant Clio (Gabriella Licudi), with whom he shares his first sexual experience. Farson encourages their coupling, believing it’ll end in tears and the young man’s mental torment will be something he can further exploit, but then everyone finds out just how bad of a poet Max really is, and they encourage him to kill himself, for real, and Max realizes that his reactionary gesture is being seen by everyone as simply a cry for attention.

Depressed by this last futile attempt to make himself understood, Max goes up to to the roof but his suicidal jump is stopped by a man who happens to be working on the roof that day — but during their struggle, the worker falls to his death, and Max escapes into the woods.

Herostratus, it should be noted, is titled for the Greek poet who sought to immortalize his own name by setting fire to the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus, in the fourth century B.C. His name was later stricken from all records until it was discovered that Alexander the Great was born the night Herostratus committed his fatal act.

This was Don Levy’s first feature film after having attending on a scholarship at Cambridge University, where he began a PhD study in Theoretical Chemical Physics. At some point Levy withdrew from his science courses and began focusing on creative endeavors, including painting and playing jazz and filmmaking. He moved over to the London-based Slade School of Fine Art, where he made a series of short science documentaries, including his most successful film, 1962’s Time Is, which explored the theories and conception of time.

James Quinn, then director of the British Film Institute, had worked with Levy onTime Is, helping him secure a grant to finish the film. He then helped the director obtain the funds — from the BFI Experimental Film Fund — to make another short film, but Levy soon found his ambitions were exceeding the budget as it expanded into a feature-length production, with additional funding coming from the BBC. That film was Herostratus, and it took five years to complete, but it was largely met with indifference, and was not the spectacular success that Levy (and Quinn) had hoped for. After a handful of initial screenings, including its premiere at London’s Institute of Contemporary Artst, in April 1968, Herostratus was shelved and virtually forgotten.

Levy’s artistic filmmaking style — juxtaposing images of postwar urban decay and burlesque stripteases with carcasses hanging in an abattoir — met largely with indifference from the public and from most film critics, even though later critics have pointed out that he did have some influence on his contemporaries, including Richard Lester and Stanley Kubrick, especially on the latter’s 1971 film Clockwork Orange.

The few surviving prints of Herostratus show it to be a flawed yet highly perceptive dissection of 1960s idealism, seduced by the Mephistophelian deception of market forces and the empty promise of mass media celebrity.

Helen Mirren’s singular contribution (about 54 minutes into the film) as “Advert Woman” provides one of the few dark moments of humor in an otherwise very dark film. In the scene, she is wearing rubber gloves for the filming of a commercial which is supposed to be a statement about consumerism, but we know what the real product is: the camera lingers lasciviously (as it will so often in her later career) over her cleavage. Once she’s delivered her lines, Gothard scoops her up and carries her off set. The scene is barely more than three minutes long.

helen mirren dealing with a totally sexist interviewer (1975)

He is vile. She handles him with brilliant wit and poise.

charity hamilton – troubled bodies: metaxu, suffering and the encounter with the divine

The body is the canvas on which the female experience is painted and through which female identity is often understood. The female body is a slate on which a patriarchal story has been written, scarred onto the flesh.

For Simone Weil metaxu was simultaneously that which separated and connected, so for instance the wall between two prison cells cuts off the prisoners but was also the means by which they communicated by knocking on that wall. Could the body be that metaxu all at once separating us and connecting us to the Divine? The nature of metaxu is that it offers a route not just for the individual soul but for the souls of others to travel…

—

It’s all well and good to dust off a dead French Jewish Catholic not-quite-feminist-philosopher called Simone Weil and say ‘thanks, your theory of metaxu is great’, but what I want to know within the bones of my so-called soul is how this notion of metaxu can draw me into God, how can it liberate my sisters and how can it usher in the kingdom of the mother of all creation?

Human beings are created in the image of God and formed from the dust of the earth, and thus the body has an echoing significance throughout Christian history. The body is the perceived seat of what some describe as the fall, the locus of the incarnation, the home of crucifixion, the vessel of redemption, salvation and resurrection. The body is not an external meaningless diversion from the spiritual path; rather it is an incredibly important recurring theme both biblically and in Christian tradition and history. Bray and Colebrook state that,

The body is a negotiation with images, but it is also a negotiation with pleasures, pains, other bodies, space, visibility, and medical practice; no single event in this field can act as a general ground for determining the status of the body (Bray and Colebrook, 1998).

Yet more than all of this, the body is the place in which we dwell, it is all we have. As Elizabeth Moltmann Wendell says ‘I am my body’ (Moltmann-Wendell, 1994). For each of our sisters the body is the canvas on which the female experience is painted and through which female identity is often understood. It is on the stage of our female bodies that some of the most fixed church doctrines have been written and enacted. The female body is a slate on which a patriarchal story has been written, scarred onto the flesh. These bodies of ours are patriarchal constructs which must be liberated and re-adopted into the Christian story without the limitations of perceived notions or definitions of ‘gender’.

Isherwood and Stuart assert that ‘From the moment we are asked to believe that Eve was a rib removed from the side of Adam we understand that theology is based in the body and we are at a disadvantage!’ (Isherwood and Stuart, 1998: 15). The historical dichotomy between the Eve and the Mary constructions has led to a definitive inequality for women, both in terms of physical wellbeing and in terms of spiritual and psychological wellbeing. The choices for a woman to be the sin-formed, temptress Eve or the virginal pure vessel Mary are seen historically in the precarious place of women in the church and in society.

Elizabeth Stuart writes that ‘Women were regarded as being ensnared in their bodiliness to a far greater degree than men and they too had to be tamed and subdued for their own good and the good of the men they might tempt into sin’ (Stuart, 1996: 23). It is hardly surprising therefore that twentieth and twenty-first century feminist, womanist, mujerista and black theologians have worked hard to undo and re-express a theology of the body which offers a more authentic narrative of the relationship between the Divine and the physical which both liberates the female body and liberates God from the patriarchal box the Church has created around her.

…The female body can only be liberated from that patriarchal overwriting by writing its own narrative, much of which will be based upon experiences of being troubled. The true nature of the female body can only be revealed by a concerted effort to ‘re-own’ this body as our own not as we have been taught to understand it. This in turn means that the systems, doctrines and ‘ways of being’ which exist within the Church and society must be challenged and re-imagined from the perspective of the un-vocalized and troubled female narrative. In the sense that the female body has not really been ours, has not been an authentically female body and yet has the potential to be unlocked as such, it therefore makes for the perfect condition for metaxu, it is that thing which separates in its forms of oppression and connects in its potential liberation. It is at once a place where great evil has been wrought and a place of divine goodness. Weil writes of love that,

Creation is an act of love and it is perpetual. At each moment our existence is God’s love for us. But God can only love himself. His love for us is love for himself through us. Thus, he who gives us our being loves in us the acceptance of not being. Our existence is made up only of his waiting for our acceptance not to exist. He is perpetually begging from us that existence which he gives. He gives it to us in order to beg it from us (Weil, 2002: 28).

According to Weil, our very existence is from God and returns to God. I would argue that to be able to return this ‘not being’ to God, the body has to take some form of action, or have some form of action performed upon it to open a space in which our not being or not existing can be offered to God. It is this removal of our self which I argue can be interpreted as a removal of the socially created self to leave only the God part of ourselves, the authentic self that is God. The body is metaxu in that it is imperfect and yet perfect. The body is human and therefore unreal and socially recreated, yet the body is also created by God and God dwells within it. The female body is both imprisoned and is liberated. Its imprisonment is the very thing that enables it to unravel the layers of patriarchal construction to locate the God part and its imprisonment is the thing which allows for an authentic narrative to be written. The female body has to separate us from the Divine in order to connect us to the Divine.

Read the whole of this interesting paper by Charity Hamilton HERE.

the slits – typical girls (1979)

Album: Cut

Year: 1979

virginia woolf – a room of one’s own (1929)

Undated photo of Virginia Woolf. (AP Photo)

I told you in the course of this paper that Shakespeare had a sister; but do not look for her in Sir Sidney Lee’s life of the poet. She died young – alas, she never wrote a word. She lies buried where the omnibuses now stop, opposite the Elephant and Castle. Now my belief is that this poet who never wrote a word and was buried at the crossroads still lives.

She lives in you and in me, and in many other women who are not here tonight, for they are washing up the dishes and putting the children to bed. But she lives; for great poets do not die; they are continuing presences; they need only the opportunity to walk among us in the flesh. This opportunity, as I think, it is now coming within your power to give her.

For my belief is that if we live another century or so – I am talking of the common life which is the real life and not of the little separate lives which we live as individuals – and have five hundred a year each of us and rooms of our own; if we have the habit of freedom and the courage to write exactly what we think; if we escape a little from the common sitting-room and see human beings not always in their relation to each other but in relation to reality; and the sky, too, and the trees or whatever it may be in themselves; if we look past Milton’s hogey, for no human being should shut out the view; if we face the fact, for it is a fact, that there is no arm to cling to, but that we go alone and that our relation is to the world of reality and not only to the world of men and women, then the opportunity will come and the dead poet who was Shakespeare’s sister will put on the body which she has so often laid down.

Drawing her life from the lives of the unknown who were her forerunners, as her brother did before her, she will be born. As for her coming without that preparation, without that effort on our part, without that determination that when she is born again she shall find it possible to live and write her poetry, that we cannot expect, for that would be impossible. But I maintain that she would come if we worked for her, and that so to work, even in poverty and obscurity, is worthwhile.

ica 3rd space symposium at uct

L-R: jackï job, Dee Moholo, Koleka Putuma, Khanyi Mbongwa (Vasiki), Ilze Wolff, Lois Anguria

The most decolonised academic space I have yet had the joy of experiencing. The conference continues today. If you’re in Cape Town, come. It’s free!

HERE is the programme. 🌸

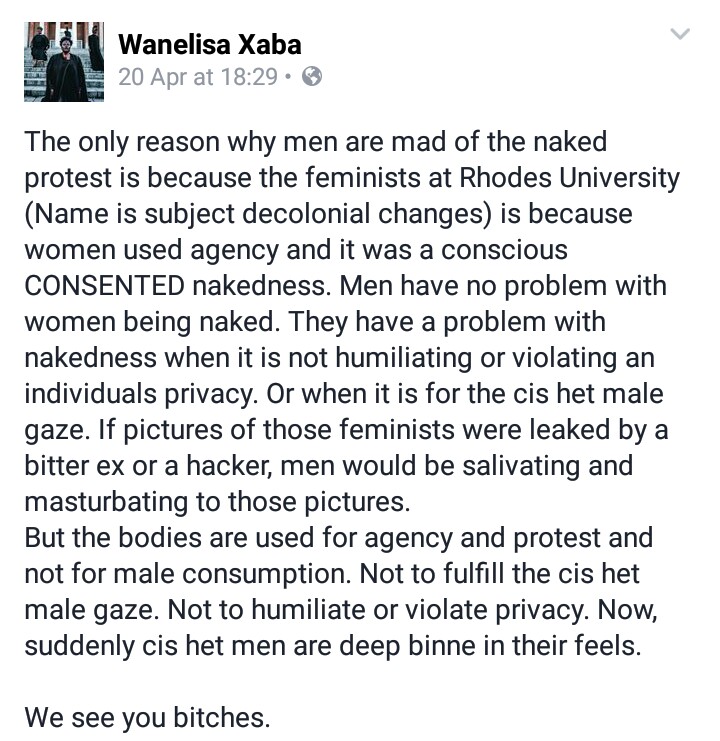

disrupt

Published on 4 May 2016

Having followed the #RUReferenceList and #RUInterdict, Activate has put together a feature-length documentary about the silencing of students and staff within the space that is currently known as Rhodes University.

DISRUPT stands to continue the conversation surrounding this mistreatment of survivors and the ways in which the university management and police have failed us. It is a direct response to the use of legalese – in the form of an interdict against involved parties – to try and force the university back into “business as usual”.

Featuring interviews with members of the student and staff body, footage from the two weeks of protest and the resulting use of police force on students and workers, DISRUPT serves as both a chronological documenting of the events of the last three weeks; but also uses the window of the #RUReferenceList protests to shine a light on the institutional issue that is rape culture.

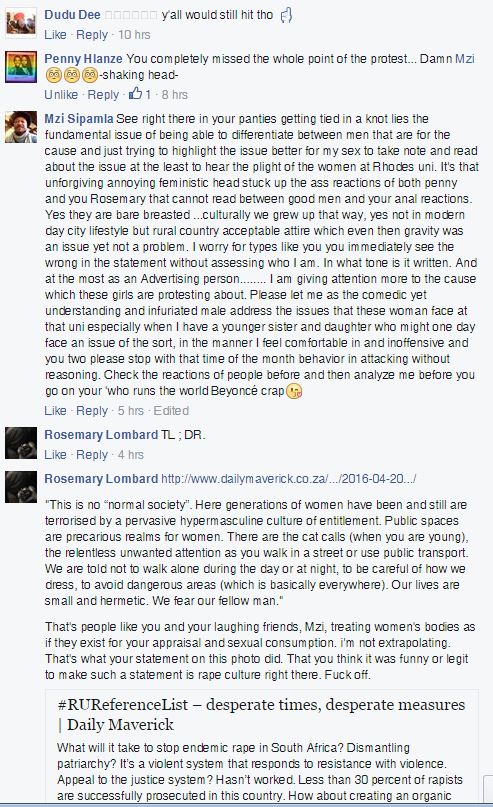

not for your gaze

today’s dose of sexism, just for example

This has made me so furious that I need to share it.

(That article linked to is HERE.)

being a girl: a brief personal history of violence

What is your narrative of misogyny? We all have one.

1.

I am six. My babysitter’s son, who is five but a whole head taller than me, likes to show me his penis. He does it when his mother isn’t looking. One time when I tell him not to, he holds me down and puts penis on my arm. I bite his shoulder, hard. He starts crying, pulls up his pants and runs upstairs to tell his mother that I bit him. I’m too embarrassed to tell anyone about the penis part, so they all just think I bit him for no reason.

I get in trouble first at the babysitter’s house, then later at home.

The next time the babysitter’s son tries to show me his penis, I don’t fight back because I don’t want to get in trouble.

One day I tell the babysitter what her son does, she tells me that he’s just a little boy, he doesn’t know…

View original post 1,529 more words

george eliot (mary ann evans) – on being disagreeable

“George Eliot” was the pen name chosen by Mary Ann Evans, a Victorian writer. She chose a male pen name so that her works were taken seriously, in response to an 1856 essay she wrote for the Westminster Review, ‘Silly Novels by Lady Novelists’.

“George Eliot” was the pen name chosen by Mary Ann Evans, a Victorian writer. She chose a male pen name so that her works were taken seriously, in response to an 1856 essay she wrote for the Westminster Review, ‘Silly Novels by Lady Novelists’.

angelo fick on upholding rape culture in south africa

“In South Africa we have no business criticizing the young with homilies about propriety and dignity, decency and politesse. There can be no equality for young women in higher education if the spaces they are supposed to study in are organized around enabling their violation by omission, silence and inaction.

“In South Africa we have no business criticizing the young with homilies about propriety and dignity, decency and politesse. There can be no equality for young women in higher education if the spaces they are supposed to study in are organized around enabling their violation by omission, silence and inaction.

The shame does not reside with the survivors, despite the insults and abuse flung at them, despite the rubber bullets fired at them, despite being wrestled to the ground for daring to object to the normalization of and silence on their violence, and the inaction of organizations and institutions.”

– Angelo Fick, 20 April 2016. Read the full piece HERE.