Fan-made video.

Category Archives: love

björk – stonemilker (forest swords remix) (2017)

This is incredible.

martha wainwright – proserpina (2012)

The last song written by her mother, Kate McGarrigle.

kate & anna mcgarrigle – walking song (1977)

my bloody valentine – to here knows when (1991)

This is for Gareth.

joanna newsom – jackrabbits (2010)

antony and the johnsons – fistful of love (2005)

nazim hikmet – things I didn’t know i loved (1962)

It’s 1962 March 28th

I’m sitting by the window on the Prague-Berlin train

night is falling

I never knew I liked

night descending like a tired bird on a smoky wet plain

I don’t like

comparing nightfall to a tired bird

I didn’t know I loved the earth

can someone who hasn’t worked the earth love it

I’ve never worked the earth

it must be my only Platonic love

and here I’ve loved rivers all this time

whether motionless like this they curl skirting the hills

European hills crowned with chateaus

or whether stretched out flat as far as the eye can see

I know you can’t wash in the same river even once

I know the river will bring new lights you’ll never see

I know we live slightly longer than a horse but not nearly as long as a crow

I know this has troubled people before

and will trouble those after me

I know all this has been said a thousand times before

and will be said after me

I didn’t know I loved the sky

cloudy or clear

the blue vault Andrei studied on his back at Borodino

in prison I translated both volumes of War and Peace into Turkish

I hear voices

not from the blue vault but from the yard

the guards are beating someone again

I didn’t know I loved trees

bare beeches near Moscow in Peredelkino

they come upon me in winter noble and modest

beeches are Russian the way poplars are Turkish

“the poplars of Izmir

losing their leaves. . .

they call me The Knife. . .

lover like a young tree. . .

I blow stately mansions sky-high”

in the Ilgaz woods in 1920 I tied an embroidered linen handkerchief

to a pine bough for luck

I never knew I loved roads

even the asphalt kind

Vera’s behind the wheel we’re driving from Moscow to the Crimea

Koktebele

formerly “Goktepé ili” in Turkish

the two of us inside a closed box

the world flows past on both sides distant and mute

I was never so close to anyone in my life

bandits stopped me on the red road between Bolu and Geredé

when I was eighteen

apart from my life I didn’t have anything in the wagon they could take

and at eighteen our lives are what we value least

I’ve written this somewhere before

wading through a dark muddy street I’m going to the shadow play

Ramazan night

a paper lantern leading the way

maybe nothing like this ever happened

maybe I read it somewhere an eight-year-old boy

going to the shadow play

Ramazan night in Istanbul holding his grandfather’s hand

his grandfather has on a fez and is wearing the fur coat

with a sable collar over his robe

and there’s a lantern in the servant’s hand

and I can’t contain myself for joy

flowers come to mind for some reason

poppies cactuses jonquils

in the jonquil garden in Kadikoy Istanbul I kissed Marika

fresh almonds on her breath

I was seventeen

my heart on a swing touched the sky

I didn’t know I loved flowers

friends sent me three red carnations in prison

I just remembered the stars

I love them too

whether I’m floored watching them from below

or whether I’m flying at their side

I have some questions for the cosmonauts

were the stars much bigger

did they look like huge jewels on black velvet

or apricots on orange

did you feel proud to get closer to the stars

I saw color photos of the cosmos in Ogonek magazine now don’t

be upset comrades but nonfigurative shall we say or abstract

well some of them looked just like such paintings which is to

say they were terribly figurative and concrete

my heart was in my mouth looking at them

they are our endless desire to grasp things

seeing them I could even think of death and not feel at all sad

I never knew I loved the cosmos

snow flashes in front of my eyes

both heavy wet steady snow and the dry whirling kind

I didn’t know I liked snow

I never knew I loved the sun

even when setting cherry-red as now

in Istanbul too it sometimes sets in postcard colors

but you aren’t about to paint it that way

I didn’t know I loved the sea

except the Sea of Azov

or how much

I didn’t know I loved clouds

whether I’m under or up above them

whether they look like giants or shaggy white beasts

moonlight the falsest the most languid the most petit-bourgeois

strikes me

I like it

I didn’t know I liked rain

whether it falls like a fine net or splatters against the glass my

heart leaves me tangled up in a net or trapped inside a drop

and takes off for uncharted countries I didn’t know I loved

rain but why did I suddenly discover all these passions sitting

by the window on the Prague-Berlin train

is it because I lit my sixth cigarette

one alone could kill me

is it because I’m half dead from thinking about someone back in Moscow

her hair straw-blond eyelashes blue

the train plunges on through the pitch-black night

I never knew I liked the night pitch-black

sparks fly from the engine

I didn’t know I loved sparks

I didn’t know I loved so many things and I had to wait until sixty

to find it out sitting by the window on the Prague-Berlin train

watching the world disappear as if on a journey of no return

19 April 1962

Moscow

__

(Thank you to Lesego Rampolokeng for showing me this poem I didn’t know I loved.❤)

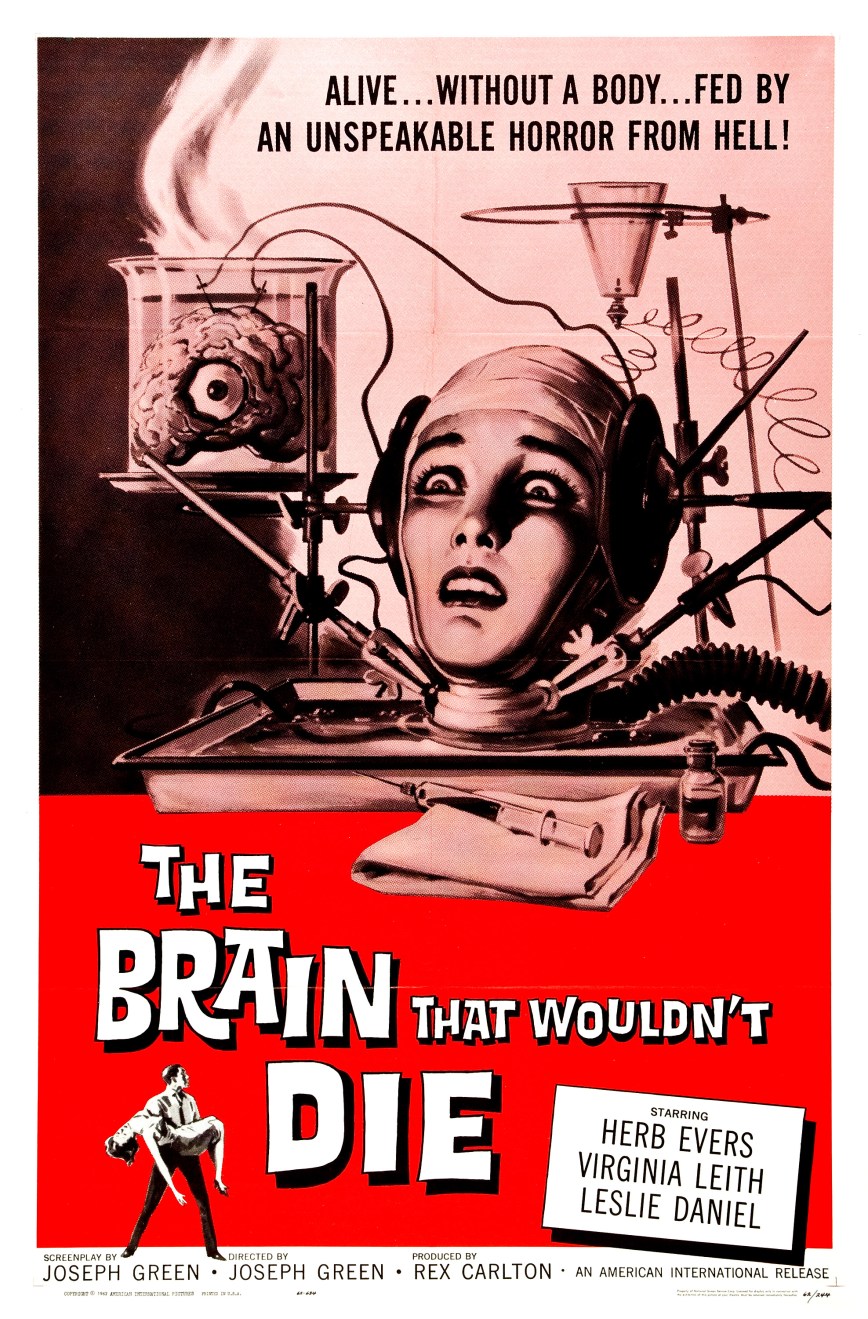

the brain that wouldn’t die (joseph green, 1962)

msaki – crimson love (2014)

Follow Asanda Msaki Mvana HERE.

the tiger lillies – stitch me up (1995)

rainer maria rilke – from “requiem for a friend” (1908)

… That’s what you had to come back for: the lament that we omitted. Can you hear me? I would like to fling my voice out like a cloth over the fragments of your death, and keep pulling at it until it is torn to pieces, and all my words would have to walk around shivering, in the tatters of that voice; as if lament were enough.

But now I must accuse: not the man who withdrew you from yourself (I cannot find him; he looks like everyone), but in this one man, I accuse: all men. When somewhere, from deep within me, there arises the vivid sense of having been a child, the purity and essence of that childhood where I once lived: then I don’t want to know it. I want to form an angel from that sense and hurl him upward, into the front row of angels who scream out, reminding God.

For this suffering has lasted far too long; none of us can bear it; it is too heavy — this tangled suffering of spurious love which, building on convention like a habit, calls itself just, and fattens on injustice. Show me a man with a right to his possession. Who can possess what cannot hold its own self, but only, now and then, will blissfully catch itself, then quickly throw itself away, like a child playing with a ball. As little as a captain can hold the carved Nike facing outward from his ship’s prow when the lightness of her godhead suddenly lifts her up, into the bright sea-wind: so little can one of us call back the woman who, now no longer seeing us, walks on along the narrow strip of her existence as though by miracle, in perfect safety — unless, that is, he wishes to do wrong. For this is wrong, if anything is wrong: not to enlarge the freedom of a love with all the inner freedom one can summon. We need, in love, to practice only this: letting each other go. For holding on comes easily; we do not need to learn it.

Are you still here? Are you standing in some corner? You knew so much of all this, you were able to do so much; you passed through life so open to all things, like an early morning. I know: women suffer; for love means being alone; and artists in their work sometimes intuit that they must keep transforming, where they love. You began both; both exist in that which any fame takes from you and disfigures. Oh you were far beyond all fame; were almost invisible; had withdrawn your beauty, softly, as one would lower a brightly colored flag on the gray morning after a holiday. You had just one desire: a year’s long work — which was never finished; was somehow never finished. If you are still here with me, if in this darkness there is still some place where your spirit resonates on the shallow sound waves stirred up by my voice: hear me: help me. We can so easily slip back from what we have struggled to attain, abruptly, into a life we never wanted; can find that we are trapped, as in a dream, and die there, without ever waking up. This can occur. Anyone who has lifted his blood into a years-long work may find that he can’t sustain it, the force of gravity is irresistible, and it falls back, worthless. For somewhere there is an ancient enmity between our daily life and the great work. Help me, in saying it, to understand it.

Do not return. If you can bear to, stay dead with the dead. The dead have their own tasks. But help me, if you can without distraction, since in me what is most distant sometimes helps.

[Translator: Stephen Mitchell]

sharon van etten – love more (2011)

bon iver – heavenly father (2014)

joan armatrading – whatever’s for us (1972)

alunageorge – i remember (2016)

virna lindt – i experienced love (1984)

wanda jackson – sweet nothing

jeff buckley – if you see her, say hello (1993)

leonard cohen – on the level (2016)

the greenhornes feat. holly golightly – there is an end (2002)

billy childish & holly golightly – i believe (1999)

naomi shihab nye – kindness (1995)

Before you know what kindness really is

you must lose things,

feel the future dissolve in a moment

like salt in a weakened broth. What you held in your hand,

what you counted and carefully saved,

all this must go so you know how desolate the landscape can be between the regions of kindness. How you ride and ride

thinking the bus will never stop,

the passengers eating maize and chicken

will stare out the window forever.

Before you learn the tender gravity of kindness

you must travel where the Indian in a white poncho

lies dead by the side of the road. You must see how this could be you,

how he too was someone

who journeyed through the night with plans

and the simple breath that kept him alive.

Before you know kindness as the deepest thing inside,

you must know sorrow as the other deepest thing.

You must wake up with sorrow.

You must speak to it till your voice

catches the thread of all sorrows

and you see the size of the cloth.

Then it is only kindness that makes sense anymore,

only kindness that ties your shoes

and sends you out into the day to gaze at bread,

only kindness that raises its head

from the crowd of the world to say

It is I you have been looking for,

and then goes with you everywhere

like a shadow or a friend.

__

Naomi Shihab Nye was born in St. Louis, Missouri in 1952. Her father was a Palestinian refugee and her mother an American of German and Swiss descent, and Nye spent her adolescence in both Jerusalem and San Antonio, Texas. Read more here.

eartha kitt on love and compromise (1982)

From the documentary All by Myself: the Eartha Kitt Story.

god is busy with ghosts and grime

What world to which you do not belong

What world to which you do not belong

What barren place, what days are these

What awful thing has laid you down

Betwixt this bed alone, you sleep

In a room of ghosts and grime and sin

With no bedding to curl against your chest

To comfort skin and heart and head

Or find reprieve, remember this:

This world to which you do not belong

Is not of you or Her or He

But a world of them, the scribbled lines

of man and man, now man-machine

What of your bed amidst their house

Do you make it, leave it, invite them in?

Or do you tie the sheets and fashion means

To hang your life, go whispering

Along the corridors where they tried to kiss you

Beneath the beams of others gone

Below the words of men who missed you

And missed the most, your unborn son

What now, what world (you’re standing yet –

You’ve left the bed and room and curse)

“What will you have me do this time

What good is left, what use of verse?”

And yonder still, the One you seek

Forever held in suspension there

Just beyond and just ahead

The endless walk to God knows where

But now the ghosts and grime are yours

Not all have seen that bathroom floor,

Fewer still, been strapped to beds;

Freed their limbs and asked for more

Folly! You live; you’re safe and sound

And most of ghosts have long since left

This talk of lover and beloved, how,

When Aleppo burns, lovers bereft

Of beloved, once in bone and flesh

Oh God (for what is God but wonder)

In what world does hell come breathing thus?

Who tears such limbs and hearts asunder?

But this is mine (you speak of light)

And that is theirs, by karma dealt

If this were true (you once were them)

You’d fall to the floor with all you felt

And further into darkness go,

With mimicry of the darkest yet,

To give all that you could and all that you are

To pray in a place where light had left

Throw glitter, glitter at every bent

Hold lightly prayers for beloved thine

You ask for more but don’t malign

A God who’s busy with ghosts and grime.

mica levi – love (2014)

This video from Mica Levi (of Micachu and the Shapes) is my favourite discovery this week.

Breathe a balloon full of kisses

Let it go where it will

And it will

🎈

sharon van etten – flirted with you all my life (2010)

This is incredible.

A cover of the 2009 Vic Chesnutt song, from the Fantasy Covers: The 2000s Part Two podcast.

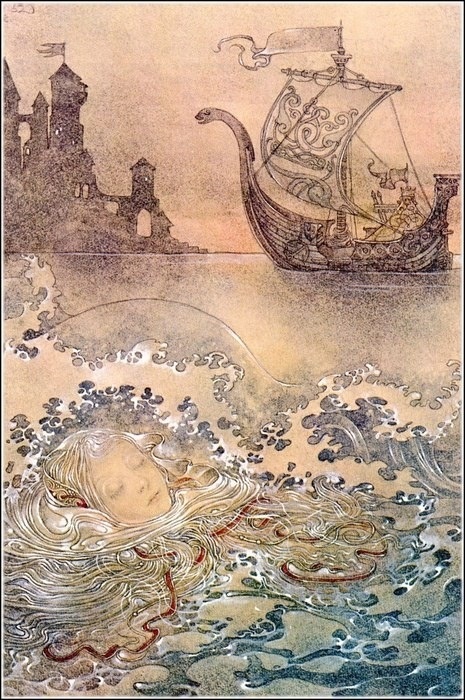

italo calvino – the distance of the moon (1965)

‘Like many a critical humanist before him, from Michel de Montaigne to Jonathan Swift, Calvino seems to wonder if our best intellectual efforts, even the sciences, fall subject to “the foibles and fancies of humans,” and to the askew narrative logic of folklore.’ I found this wonderful thing via Open Culture. I had to go and find the story on which the animation is based, and when I did, I had to share it with you, at new moon.

The Distance of the Moon

At one time, according to Sir George H. Darwin, the Moon was very close to the Earth. Then the tides gradually pushed her far away: the tides that the Moon herself causes in the Earth’s waters, where the Earth slowly loses energy.

How well I know! — old Qfwfq cried,– the rest of you can’t remember, but I can. We had her on top of us all the time, that enormous Moon: when she was full — nights as bright as day, but with a butter-colored light — it looked as if she were going to crush us; when she was new, she rolled around the sky like a black umbrella blown by the wind; and when she was waxing, she came forward with her horns so low she seemed about to stick into the peak of a promontory and get caught there. But the whole business of the Moon’s phases worked in a different way then: because the distances from the Sun were different, and the orbits, and the angle of something or other, I forget what; as for eclipses, with Earth and Moon stuck together the way they were, why, we had eclipses every minute: naturally, those two big monsters managed to put each other in the shade constantly, first one, then the other.

Orbit? Oh, elliptical, of course: for a while it would huddle against us and then it would take flight for a while. The tides, when the Moon swung closer, rose so high nobody could hold them back. There were nights when the Moon was full and very, very low, and the tide was so high that the Moon missed a ducking in the sea by a hair’s breadth; well, let’s say a few yards anyway. Climb up on the Moon? Of course we did. All you had to do was row out to it in a boat and, when you were underneath, prop a ladder against her and scramble up.

The spot where the Moon was lowest, as she went by, was off the Zinc Cliffs. We used to go out with those little rowboats they had in those days, round and flat, made of cork. They held quite a few of us: me, Captain Vhd Vhd, his wife, my deaf cousin, and sometimes little Xlthlx — she was twelve or so at that time. On those nights the water was very calm, so silvery it looked like mercury, and the fish in it, violet-colored, unable to resist the Moon’s attraction, rose to the surface, all of them, and so did the octopuses and the saffron medusas. There was always a flight of tiny creatures — little crabs, squid, and even some weeds, light and filmy, and coral plants — that broke from the sea and ended up on the Moon, hanging down from that lime-white ceiling, or else they stayed in midair, a phosphorescent swarm we had to drive off, waving banana leaves at them.

This is how we did the job: in the boat we had a ladder: one of us held it, another climbed to the top, and a third, at the oars, rowed until we were right under the Moon; that’s why there had to be so many of us (I only mentioned the main ones). The man at the top of the ladder, as the boat approached the Moon, would become scared and start shouting: “Stop! Stop! I’m going to bang my head!” That was the impression you had, seeing her on top of you, immense, and all rough with sharp spikes and jagged, saw-tooth edges. It may be different now, but then the Moon, or rather the bottom, the underbelly of the Moon, the part that passed closest to the Earth and almost scraped it, was covered with a crust of sharp scales. It had come to resemble the belly of a fish, and the smell too, as I recall, if not downright fishy, was faintly similar, like smoked salmon.

In reality, from the top of the ladder, standing erect on the last rung, you could just touch the Moon if you held your arms up. We had taken the measurements carefully (we didn’t yet suspect that she was moving away from us); the only thing you had to be very careful about was where you put your hands. I always chose a scale that seemed fast (we climbed up in groups of five or six at a time), then I would cling first with one hand, then with both, and immediately I would feel ladder and boat drifting away from below me, and the motion of the Moon would tear me from the Earth’s attraction. Yes, the Moon was so strong that she pulled you up; you realized this the moment you passed from one to the other: you had to swing up abruptly, with a kind of somersault, grabbing the scales, throwing your legs over your head, until your feet were on the Moon’s surface. Seen from the Earth, you looked as if you were hanging there with your head down, but for you, it was the normal position, and the only odd thing was that when you raised your eyes you saw the sea above you, glistening, with the boat and the others upside down, hanging like a bunch of grapes from the vine.

My cousin, the Deaf One, showed a special talent for making those leaps. His clumsy hands, as soon as they touched the lunar surface (he was always the first to jump up from the ladder), suddenly became deft and sensitive. They found immediately the spot where he could hoist himself up; in fact just the pressure of his palms seemed enough to make him stick to the satellite’s crust. Once I even thought I saw the Moon come toward him, as he held out his hands.

He was just as dextrous in coming back down to Earth, an operation still more difficult. For us, it consisted in jumping, as high as we could, our arms upraised (seen from the Moon, that is, because seen from the Earth it looked more like a dive, or like swimming downwards, arms at our sides), like jumping up from the Earth in other words, only now we were without the ladder, because there was nothing to prop it against on the Moon. But instead of jumping with his arms out, my cousin bent toward the Moon’s surface, his head down as if for a somersault, then made a leap, pushing with his hands. From the boat we watched him, erect in the air as if he were supporting the Moon’s enormous ball and were tossing it, striking it with his palms; then, when his legs came within reach, we managed to grab his ankles and pull him down on board.

Now, you will ask me what in the world we went up on the Moon for; I’ll explain it to you. We went to collect the milk, with a big spoon and a bucket. Moon-milk was very thick, like a kind of cream cheese. It formed in the crevices between one scale and the next, through the fermentation of various bodies and substances of terrestrial origin which had flown up from the prairies and forests and lakes, as the Moon sailed over them. It was composed chiefly of vegetal juices, tadpoles, bitumen, lentils, honey, starch crystals, sturgeon eggs, molds, pollens, gelatinous matter, worms, resins, pepper, mineral salts, combustion residue. You had only to dip the spoon under the scales that covered the Moon’s scabby terrain, and you brought it out filled with that precious muck. Not in the pure state, obviously; there was a lot of refuse. In the fermentation (which took place as the Moon passed over the expanses of hot air above the deserts) not all the bodies melted; some remained stuck in it: fingernails and cartilage, bolts, sea horses, nuts and peduncles, shards of crockery, fishhooks, at times even a comb. So this paste, after it was collected, had to be refined, filtered. But that wasn’t the difficulty: the hard part was transporting it down to the Earth. This is how we did it: we hurled each spoonful into the air with both hands, using the spoon as a catapult. The cheese flew, and if we had thrown it hard enough, it stuck to the ceiling, I mean the surface of the sea. Once there, it floated, and it was easy enough to pull it into the boat. In this operation, too, my deaf cousin displayed a special gift; he had strength and a good aim; with a single, sharp throw, he could send the cheese straight into a bucket we held up to him from the boat. As for me, I occasionally misfired; the contents of the spoon would fail to overcome the Moon’s attraction and they would fall back into my eye.

I still haven’t told you everything, about the things my cousin was good at. That job of extracting lunar milk from the Moon’s scales was child’s play to him: instead of the spoon, at times he had only to thrust his bare hand under the scales, or even one finger. He didn’t proceed in any orderly way, but went to isolated places, jumping from one to the other, as if he were playing tricks on the Moon, surprising her, or perhaps tickling her. And wherever he put his hand, the milk spurted out as if from a nanny goat’s teats. So the rest of us had only to follow him and collect with our spoons the substance that he was pressing out, first here, then there, but always as if by chance, since the Deaf One’s movements seemed to have no clear, practical sense.

There were places, for example, that he touched merely for the fun of touching them: gaps between two scales, naked and tender folds of lunar flesh. At times my cousin pressed not only his fingers but — in a carefully gauged leap — his big toe (he climbed onto the Moon barefoot) and this seemed to be the height of amusement for him, if we could judge by the chirping sounds that came from his throat as he went on leaping. The soil of the Moon was not uniformly scaly, but revealed irregular bare patches of pale, slippery clay.

These soft areas inspired the Deaf One to turn somersaults or to fly almost like a bird, as if he wanted to impress his whole body into the Moon’s pulp. As he ventured farther in this way, we lost sight of him at one point. On the Moon there were vast areas we had never had any reason or curiosity to explore, and that was where my cousin vanished; I had suspected that all those somersaults and nudges he indulged in before our eyes were only a preparation, a prelude to something secret meant to take place in the hidden zones.

We fell into a special mood on those nights off the Zinc Cliffs: gay, but with a touch of suspense, as if inside our skulls, instead of the brain, we felt a fish, floating, attracted by the Moon. And so we navigated, playing and singing. The Captain’s wife played the harp; she had very long arms, silvery as eels on those nights, and armpits as dark and mysterious as sea urchins; and the sound of the harp was sweet and piercing, so sweet and piercing it was almost unbearable, and we were forced to let out long cries, not so much to accompany the music as to protect our hearing from it. Continue reading

siphokazi jonas – extraction (2016)

Listen. This woman’s words will transport you beyond the brutality, the sordid pettiness of humanity, and restore to you the depth of timeless Truth, which is Love. Give thanks with every atom of your being.

The stone is a room

Without windows or doors

Or floors.

The stone is a fist – holds

Captive a handful of broken bones

And perfect thorns.

The body of the stone does not conceive

She is a muted womb, a blunt fallopian tube

With a uterus like Jericho,

Her walls are always seven days

Away from falling.

She lies submerged

In an ocean without borders,

A stranger to shores.

Even the bulldozing tide cannot breach her pores,

What! with her lungs unravelled and

Worn like second skin to seal herself

From the influence of

The Spirit which hovers outside like breath.

She no longer desires to

Shatter surfaces and float.

A student to necessities of survival

She has taught herself to harness tornadoes like cattle and

To plow the dark and

Bury her solitude in the saline barrenness

Of the ocean floor –

The silence of the deep

Is graveyard.

From between tombstone lips she counts each body by name:

There is buried Faith.

There rests what is left of Peace,

In that corner is Love

In all its inglorious manifestations

And here lies Hope. Cremated.

She makes home in the company of ghosts

Where she once prayed for their resurrection.

Finds comfort

In the erosion and corrosion

Of a current without conscience

Surrendering to her inability to preserve things

To keep them from hitchhiking

On the tide and sailing away.

She is rooted in shadows here

Is undisturbed here

Wounds are familiar here

Healing is unwelcome here

Pain is a refugee here

Pretends to the point of believing

That the water in her lungs is air. Here.

Who would recognise

The tears of a stone submerged

In an ocean, without borders?

In this reluctant baptism

How can she know, that

She has all of God’s attention?

A Sculptor in love with a drowning stone.

In the beginning was a message in a bottle. He writes:

You say

To face God uncensored

Feels like almost dying

Feels like dying, almost.

Of course, life is a curse to those at

Peace with their death.

You ask

Who could love a stone without form

In the darkness, in the deep?

I have had feelings for you

Since before existence.

I have only created time to mark

Our first encounter.

This first love will not be relegated

To forgetfulness the tombs of memory.

Just

Give me six days to woo you.

For your sake, I will

Disguise myself as language.

My voice is a birth canal

Each word born a seed

That sprouts in speech

Each letter a bristle on a broom

To clear the air

I have always seen you

Crocheted and crafted you

In imagination

Every thread of DNA was designed

In thought

You are what I intended

Let there be light – that you might

See Me too

Hands First

Let them be home

Here the universe sleeps

Without anxiety and

Your name is a constellation that

Pre-dates the stars

Tattooed in nails

These palms are promises

Eager to cradle a rolling stone

These palms are day and revelation

They will anchor you in untethered night

When you do not see me

Acquaint yourself with the fingerprint of my works.

I will abolish the waters at the compulsion

Of my tongue, like a staff

Under the sea my word forges dry ground

And the tide will not go further

Than my command.

I could offer bouquets of flowers exiled from their roots

Or carpet petals at your feet

But the borders of my affection

Traverse generations

That the children of a stone

Might not forget the attention of Sculptor

You will buckle under the weight of my tenderness

Until you transform into flesh then spirit

And the spirit is clay, is soil, is field is fertility.

Let me dress you up from within

Make you an anchor for roots

Here you will yield fruit

like Russian dolls

You will bear

Seeds within seeds within seeds

Within season. A stone will be paradise.

For living things to gather

The site of resurrection for buried things

Wild and tame,

By air or on land.

The stone is a mine

Of precious things

The stone is mine.

Here are two rings

Their names are sun and moon

Sprinkled with galaxies and stars for gemstones

Encased in velvet heavens

This my proposal

In balls of fire and light

Wear them day or night

Until we reunite.

Now rest.

It is Sabbath.

****

The value of a precious stone

Lies in its cost to the one who will find it

Ask the Saviour of this blue and green culprit

Exchanged His life just to mine it

Day 6 set aside to carve it

With His hands until He fit it

Into His image. There can be no counterfeit

Not when the price was God in

A human outfit

Tell a poet

Who chisels words

Between papers and pens

But she will never be the Word

Only its subsidiary

Remind her

A stone can never earn or diminish

The love of a Rock

That stood before the beginning

All her attempts to give herself value

Are dust. Now mud. Now wrinkled.

The philosophies of one who has

Been in the water too long.

We are stones submerged

In the distortion of waters

Our separations from God are sirens

Singing us into

Resistance and suicide.

Tell that stone resident under your ribs

It is only precious

Because of the love of a Sculptor

7 billion stones drowning

In an ocean without borders

Some reluctant for rescue

Even if we refuse the proposal

The love of an ageless Rock will outlast

The extinction of time itself.

___

Siphokazi’s website is HERE.

sharon jones & the dap-kings – 100 days, 100 nights (2007)

Rest in peace. 💛