― Nick Hornby, High Fidelity

Category Archives: writing

thokozani mthiyane – from the mad man’s diary

ntozake shange – dark phrases

dark phrases of womanhood

of never havin been a girl

half-notes scattered

without rhythm/no tune

distraught laughter fallin

over a black girl’s shoulder

it’s funny/it’s hysterical

the melody-less-ness of her dance

don’t tell nobody don’t tell a soul

she’s dancin on beer cans & shingles

this must be the spook house

another song with no singers

lyrics/no voices

& interrupted solos

unseen performances

are we ghouls?

children of horror?

the joke?

don’t tell nobody don’t tell a soul

are we animals? have we gone crazy?

i can’t hear anythin

but maddening screams

& the soft strains of death

& you promised me

you promised me…

somebody/anybody

sing a black girl’s song

bring her out

to know herself

to know you

but sing her rhythms

carin/struggle/hard times

sing her song of life

she’s been dead so long

closed in silence so long

she doesn’t know the sound

of her own voice

her infinite beauty

she’s half-notes scattered

without rhythm/no tune

sing her sighs

sing the song of her possibilities

sing a righteous gospel

let her be born

let her be born

& handled warmly.

— from For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf. Macmillan Publishing, 1977. Shange was born Paulette L. Williams in Trenton, New Jersey. She later changed her name to isiXhosa/isiZulu – read more HERE.

anne carson – the gender of sound

Madness and witchery as well as bestiality are conditions commonly associated with the use of the female voice in public, in ancient as well as modern contexts. Consider how many female celebrities of classical mythology, literature and cult make themselves objectionable by the way they use their voice.

For example, there is the heart-chilling groan of the Gorgon, whose name is derived from a Sanskrit word, *garg meaning “a guttural animal howl that issues as a great wind from the back of the throat through a hugely distended mouth”. There are the Furies whose high-pitched and horrendous voices are compared by Aiskhylos to howling dogs or sounds of people being tortured in hell (Eumenides). There is the deadly voice of the Sirens and the dangerous ventriloquism of Helen (Odyssey) and the incredible babbling of Kassandra (Aiskhylos, Agamemnon) and the fearsome hullabaloo of Artemis as she charges through the woods (Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite). There is the seductive discourse of Aphrodite which is so concrete an aspect of her power that she can wear it on her belt as a physical object or lend it to other women (Iliad). There is the old woman of Eleusinian legend Iambe who shrieks obscenities and throws her skirt up over her head to expose her genitalia. There is the haunting garrulity of the nymph Echo (daughter of Iambe in Athenian legend) who is described by Sophokles as “the girl with no door on her mouth” (Philoktetes).

Putting a door on the female mouth has been an important project of patriarchal culture from antiquity to the present day. Its chief tactic is an ideological association of female sound with monstrosity, disorder and death.

— From “The Gender of Sound”, in Glass, Irony and God. New Directions, 1995: pp 120-121

The brilliant Anne Carson presents a history of the gendered voice, from Sophocles to Gertrude Stein. She outlines what is at stake in our assumptions around sound, questioning whether the concept of ‘self-control’ is a barrier to acknowledging other forms of human order, feeding into wider debates on social order, both past and present.

Read the whole essay HERE.

was salinger too pure for this world?

By JOYCE MAYNARD in the New York Times, September 14, 2013

“As the mother of a daughter myself, I would say that a man who treats those offering up their love and trust as expendable is lesser himself for having done so.”

In the 50 years since J.D. Salinger removed himself from the public eye and stopped publishing, he has been viewed — more accurately, worshiped — as the human embodiment of purity, a welcome antidote to phoniness. To many, he was a kind of god.

Now comes the word — though not really news, to some — that over the years when he was cherishing his privacy, Salinger was also carrying on relationships with young women 15, and in my case, 35 years younger than he.

“Salinger,” a new documentary film touches — though politely — on the story of just five of these young women (most under 20 when he sought them out), but the pattern was wider: letters I’ve received over the 15 years since I broke the unwritten rule and spoke of my own experiences with the man revealed to me that there were more than a dozen. In at least one case, Salinger was corresponding with one teenage girl while sharing his home with another: me.

Like many of the others involved, I was a young person in possession of particular vulnerabilities as well as strengths — a story that began with my family, not Salinger, and inspired me to seek out an Ivy League education with the dream of becoming a writer. Nine months after I arrived at Yale, having published a story that attracted Salinger’s attention, I received a letter from him. Then many more.

I was 18 when he wrote to me in the irresistible voice of Holden Caulfield, though he was 53 at the time. Within months I left school to live with Salinger; gave up my scholarship; severed relationships with friends; disconnected from my family; forswore all books, music, food and ideas not condoned by him. At the time, I believed I’d be with Jerry Salinger forever.

His was a seduction played out with words and ideas, not lovemaking, but to the young girl reading those words — as with a few million other readers — there could have been no more powerful allure.

Salinger wasn’t simply brilliant, funny, wise; he burrowed into one’s brain, seeming to understand things nobody else ever had. His expressions of admiration (“I couldn’t have created a character I love more than you”) were intoxicating. His dismissal and contempt, when they came, were devastating.

I was 19 when he put two $50 bills in my hand and sent me away. Years after he dismissed me, his voice stayed in my head, offering opinions on everything he loved and all that he condemned. This was true even though, on his list of the condemned, was my own self.

This was not made easier by Salinger’s unwritten edict on secrecy: if Salinger wrote you a letter, you must never say you received it. If he broke your heart you must never mention it happened. To do anything else constituted more than the violation of the privacy of a great writer; it was proof of one’s own reprobate soul, the exploitation (a word with which I’ve grown familiar over the years) of a man so much purer than the false and shallow world around him, an artist who wanted only to be left alone.

To a stunning degree, for a period of over half a century, Salinger managed to convince a significant portion of the reading population that his words and actions should be exempt from scrutiny for the simple reason that he wrote those nine stories, and “The Catcher in the Rye.” And because he said so.

Now the story well known to me is known to the world, though there are voices raised up still, decrying the violation of Salinger’s legendary privacy. But while this recent burst of disclosure might seem to demystify the man (or call his role as sage into question), a troubling phenomenon has surfaced along with the news.

It is the quiet acceptance, apparently alive and well in our culture, of the notion that genius justifies cruel or abusive treatment of those who serve the artist and his art. Richard Schickel, writing of Salinger’s activities, expresses the view that despite the disclosures about Salinger’s pursuit of young women he lived “a ‘normal’ life.”

“He liked pretty young girls. Stop the presses,” writes the film critic (and father of daughters) David Edelstein. The implication being, what’s the fuss?

One of these girls, 14 when Salinger first pursued her long ago, described him in terms usually reserved for deities, and spoke of feeling privileged to have served as inspiration and muse to a great writer — though she also reports that he severed their relationship the day after their one and only sexual encounter.

Some will argue that you can’t have it both ways: how can a woman say she is fully in charge of her body and her destiny, and then call herself a victim when, having given a man her heart of her own volition, he crushes it? How can a consensual relationship, as Salinger’s unquestionably were, constitute a form of abuse?

But we are talking about what happens when people in positions of power — mentors, priests, employers or simply those assigned an elevated status — use their power to lure much younger people into sexual and (in the case of Salinger) emotional relationships. Most typically, those who do this are men. And when they are done with the person they’ve drawn toward them, it can take that person years or decades to recover.

Continue reading this New York Times article HERE.

piotr dumala – crime and punishment (2001)

Trained as a sculptor as well as an animator, Piotr Dumala calls his innovative stop-motion technique in which an image is scratched into painted plaster, then painted over and the next image scratched on top “destructive animation”. He devised the method while studying art conservation at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts.

Crime and Punishment (Zbrodnia i Kara), Dumala’s expressionist half-hour long Dostoevsky adaptation, is a succession of shadowy, minimalist tableaux that emerge slowly from darkness and return to it. Stripping the Russian masterwork down to two scenes — the murder and Raskolnikov’s meeting of Sonia — Dumala interprets the novel’s themes with chiaroscuro intensity, choosing to highlight just a few strands of the story:

“It was not my aim to copy the book. I was really close to the book. I took one level of the book. It’s not possible to show everything from this book… This is about love and how obsession can destroy love. In our life we are under two opposite influences to be good or bad and to love or hate.”

In the worlds Dumala sketches, the lines between light and darkness are stark, but also shifting and mutable.

Read more about the background to Dumala and this film in Chris Robinson’s article for Animation World Magazine, HERE.

stephen fry on enduring

I used many times to touch my own chest and feel, under its asthmatic quiver, the engine of the heart and lungs and blood and feel amazed at what I sensed was the enormity of the power I possessed. Not magical power, but real power. The power simply to go on, the power to endure, that is power enough, but I felt I had also the power to create, to add, to delight, to amaze and to transform.

― Stephen Fry, from his autobiography, Moab Is My Washpot (Random House, 1997)

hélène cixous – the laugh of the medusa (1976)

Hello, reader :)

It’s Fleurmach’s first birthday! To celebrate, here is a ground-shifting text, a manifesto of sorts, from Hélène Cixous back in 1976 (the year punk broke). If you haven’t ever read Cixous (and even if you have, once upon a time), do yourself a favour and plough through this, SERIOUSLY. I tried to excerpt chunks from it (and may still), but decided that it’s really important and enriching to read the piece in its entirety.

Thank you all for your ongoing support and contributions to the Fleurmach community.

Much love,

Cherry Bomb

I shall speak about women’s writing: about what it will do. Woman must write her self: must write about women and bring women to writing, from which they have been driven away as violently as from their bodies – for the same reasons, by the same law, with the same fatal goal.

Woman must put herself into the text – as into the world and into history – by her own movement.

The future must no longer be determined by the past. I do not deny that the effects of the past are still with us. But I refuse to strengthen them by repeating them, to confer upon them an irremovability the equivalent of destiny, to confuse the biological and the cultural. Anticipation is imperative.

Since these reflections are taking shape in an area just on the point of being discovered, they necessarily bear the mark of our time-a time during which the new breaks away from the old, and, more precisely, the (feminine) new from the old (la nouvelle de l’ancien). Thus, as there are no grounds for establishing a discourse, but rather an arid millennial ground to break, what I say has at least two sides and two aims: to break up, to destroy; and to foresee the unforeseeable, to project.

I write this as a woman, toward women. When I say “woman”, I’m speaking of woman in her inevitable struggle against conventional man; and of a universal woman subject who must bring women to their senses and to their meaning in history. But first it must be said that in spite of the enormity of the repression that has kept them in the “dark” – that dark which people have been trying to make them accept as their attribute – there is, at this time, no general woman, no one typical woman. What they have in common I will say. But what strikes me is the infinite richness of their individual constitutions: you can’t talk about a female sexuality, uniform, homogeneous, classifiable into codes – any more than you can talk about one unconscious resembling another.

Women’s imaginary is inexhaustible, like music, painting, writing: their stream of phantasms is incredible.

I have been amazed more than once by a description a woman gave me of a world all her own which she had been secretly haunting since early childhood. A world of searching, the elaboration of a knowledge, on the basis of a systematic experimentation with the bodily functions, a passionate and precise interrogation of her erotogeneity. This practice, extraordinarily rich and inventive, in particular as concerns masturbation, is prolonged or accompanied by a production of forms, a veritable aesthetic activity, each stage of rapture inscribing a resonant vision, a composition, something beautiful. Beauty will no longer be forbidden.

I wished that that woman would write and proclaim this unique empire so that other women, other unacknowledged sovereigns, might exclaim: I, too, overflow; my desires have invented new desires, my body knows unheard-of songs. Time and again I, too, have felt so full of luminous torrents that I could burst – burst with forms much more beautiful than those which are put up in frames and sold for a stinking fortune. And I, too, said nothing, showed nothing; I didn’t open my mouth, I didn’t repaint my half of the world. I was ashamed. I was afraid, and I swallowed my shame and my fear. I said to myself: You are mad! What’s the meaning of these waves, these floods, these outbursts?

Where is the ebullient, infinite woman who, immersed as she was in her naïveté, kept in the dark about herself, led into self-disdain by the great arm of parental-conjugal phallocentrism, hasn’t been ashamed of her strength? Who, surprised and horrified by the fantastic tumult of her drives (for she was made to believe that a well-adjusted normal woman has a … divine composure), hasn’t accused herself of being a monster?

Who, feeling a funny desire stirring inside her (to sing, to write, to dare to speak, in short, to bring out something new), hasn’t thought she was sick? Well, her shameful sickness is that she resists death, that she makes trouble.

And why don’t you write? Write! Writing is for you, you are for you; your body is yours, take it. I know why you haven’t written. (And why I didn’t write before the age of twenty-seven.) Because writing is at once too high, too great for you, it’s reserved for the great – that is, for “great men”; and it’s “silly.” Besides, you’ve written a little, but in secret. And it wasn’t good, because it was in secret, and because you punished yourself for writing, because you didn’t go all the way; or because you wrote, irresistibly, as when we would masturbate in secret, not to go further, but to attenuate the tension a bit, just enough to take the edge off. And then as soon as we come, we go and make ourselves feel guilty – so as to be forgiven; or to forget, to bury it until the next time.

Write, let no one hold you back, let nothing stop you: not man; not the imbecilic capitalist machinery, in which publishing houses are the crafty, obsequious relayers of imperatives handed down by an economy that works against us and off our backs; and not yourself.

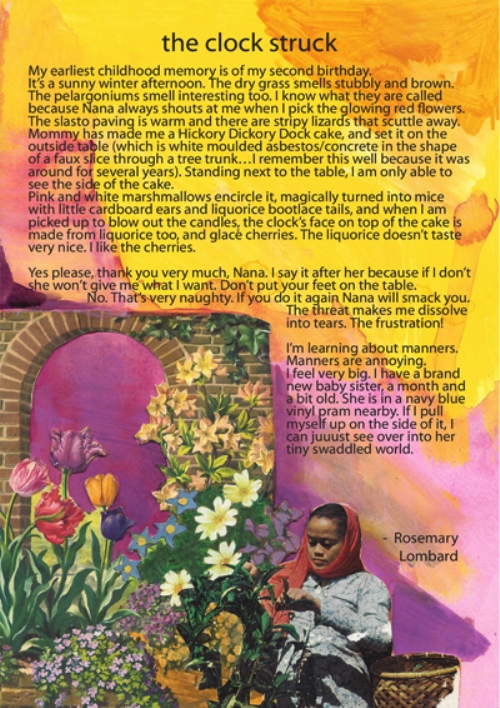

cherry bomb – the clock struck

This is a page taken from FLEURZINE, a zine curated and illustrated by Julia Mary Grey. You can go and download this beautiful work of art for free on her site, HERE.

The name was inspired by Fleurmach, and six pieces of writing from this blog appear in the publication. This piece is by Fleurmach curator Cherry Bomb and was first posted HERE.

ella jara – sweets for thohoyandou

This is a page taken from FLEURZINE, a zine curated and illustrated by Julia Mary Grey. You can go and download this beautiful work of art for free on her site, HERE.

The name was inspired by Fleurmach, and six pieces of writing from this blog appear in the publication. This piece is by Fleurmach contributor NoHolyCows, and first appeared HERE.

the fabulous bloar of margaret atwood

Toby stares at them, fascinated: she’s never seen a liobam in the flesh, only pictures. Am I imagining things? she wonders. No, the liobams are actual. They must be zoo animals freed by one of the more fanatical sects in those last desperate days.

They don’t look dangerous, although they are. The lion-sheep splice was commissioned by the Lion Isaiahists in order to force the advent of the Peaceable Kingdom. They’d reasoned that the only way to fulfil the lion/lamb friendship prophecy without the first eating the second would be to meld the two of them together. But the result hadn’t been strictly vegetarian.

Still, the liobams seem gentle enough, with their curly golden hair and twirling tails. They’re nibbling flower heads, they don’t look up; yet she has the sense that they’re perfectly aware of her. Then the male opens its mouth, displaying its long, sharp canines, and calls. It’s an odd combination of baa and roar: a bloar, thinks Toby.

— from Margaret Atwood’s The Year of the Flood (Doubleday, 2009)

saskia druyan – miss rosemary and i

This is a page taken from FLEURZINE, a zine curated and illustrated by Julia Mary Grey. You can go and download this beautiful work of art for free on her site, HERE.

This is a page taken from FLEURZINE, a zine curated and illustrated by Julia Mary Grey. You can go and download this beautiful work of art for free on her site, HERE.

The name was inspired by Fleurmach, and six pieces of writing from this blog appear in the publication!

david foster wallace on life before death

David Foster Wallace was arguably one of the most brilliant American writers of his generation. In this excerpt from a speech he gave, first published on the Guardian website a week after his death in 2008, he reflects on the difficulties of daily life and ‘making it to 30, or maybe 50, without wanting to shoot yourself in the head’. Read it below the jump or listen to the audio recording here:

There are these two young fish swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, “Morning, boys, how’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, “What the hell is water?”

If you’re worried that I plan to present myself here as the wise old fish explaining what water is, please don’t be. I am not the wise old fish. The immediate point of the fish story is that the most obvious, ubiquitous, important realities are often the ones that are the hardest to see and talk about. Stated as an English sentence, of course, this is just a banal platitude – but the fact is that, in the day-to-day trenches of adult existence, banal platitudes can have life-or-death importance. That may sound like hyperbole, or abstract nonsense. So let’s get concrete …

A huge percentage of the stuff that I tend to be automatically certain of is, it turns out, totally wrong and deluded. Here’s one example of the utter wrongness of something I tend to be automatically sure of: everything in my own immediate experience supports my deep belief that I am the absolute centre of the universe, the realest, most vivid and important person in existence. We rarely talk about this sort of natural, basic self-centredness, because it’s so socially repulsive, but it’s pretty much the same for all of us, deep down. It is our default setting, hard-wired into our boards at birth. Think about it: there is no experience you’ve had that you were not at the absolute centre of. The world as you experience it is right there in front of you, or behind you, to the left or right of you, on your TV, or your monitor, or whatever. Other people’s thoughts and feelings have to be communicated to you somehow, but your own are so immediate, urgent, real – you get the idea. But please don’t worry that I’m getting ready to preach to you about compassion or other-directedness or the so-called “virtues”. This is not a matter of virtue – it’s a matter of my choosing to do the work of somehow altering or getting free of my natural, hard-wired default setting, which is to be deeply and literally self-centred, and to see and interpret everything through this lens of self.

By way of example, let’s say it’s an average day, and you get up in the morning, go to your challenging job, and you work hard for nine or ten hours, and at the end of the day you’re tired, and you’re stressed out, and all you want is to go home and have a good supper and maybe unwind for a couple of hours and then hit the rack early because you have to get up the next day and do it all again. But then you remember there’s no food at home – you haven’t had time to shop this week, because of your challenging job – and so now, after work, you have to get in your car and drive to the supermarket. It’s the end of the workday, and the traffic’s very bad, so getting to the store takes way longer than it should, and when you finally get there the supermarket is very crowded, because of course it’s the time of day when all the other people with jobs also try to squeeze in some grocery shopping, and the store’s hideously, fluorescently lit, and infused with soul-killing Muzak or corporate pop, and it’s pretty much the last place you want to be, but you can’t just get in and quickly out: you have to wander all over the huge, overlit store’s crowded aisles to find the stuff you want, and you have to manoeuvre your junky cart through all these other tired, hurried people with carts, and of course there are also the glacially slow old people and the spacey people and the kids who all block the aisle and you have to grit your teeth and try to be polite as you ask them to let you by, and eventually, finally, you get all your supper supplies, except now it turns out there aren’t enough checkout lanes open even though it’s the end-of-the-day rush, so the checkout line is incredibly long, which is stupid and infuriating, but you can’t take your fury out on the frantic lady working the register.

Anyway, you finally get to the checkout line’s front, and pay for your food, and wait to get your cheque or card authenticated by a machine, and then get told to “Have a nice day” in a voice that is the absolute voice of death, and then you have to take your creepy flimsy plastic bags of groceries in your cart through the crowded, bumpy, littery parking lot, and try to load the bags in your car in such a way that everything doesn’t fall out of the bags and roll around in the trunk on the way home, and then you have to drive all the way home through slow, heavy, SUV-intensive rush-hour traffic, etc, etc.

The point is that petty, frustrating crap like this is exactly where the work of choosing comes in. Because the traffic jams and crowded aisles and long checkout lines give me time to think, and if I don’t make a conscious decision about how to think and what to pay attention to, I’m going to be pissed and miserable every time I have to food-shop, because my natural default setting is the certainty that situations like this are really all about me, about my hungriness and my fatigue and my desire to just get home, and it’s going to seem, for all the world, like everybody else is just in my way, and who are all these people in my way? And look at how repulsive most of them are and how stupid and cow-like and dead-eyed and nonhuman they seem here in the checkout line, or at how annoying and rude it is that people are talking loudly on cell phones in the middle of the line, and look at how deeply unfair this is: I’ve worked really hard all day and I’m starved and tired and I can’t even get home to eat and unwind because of all these stupid goddamn people.

Or if I’m in a more socially conscious form of my default setting, I can spend time in the end-of-the-day traffic jam being angry and disgusted at all the huge, stupid, lane-blocking SUVs and Hummers and V12 pickup trucks burning their wasteful, selfish, 40-gallon tanks of gas, and I can dwell on the fact that the patriotic or religious bumper stickers always seem to be on the biggest, most disgustingly selfish vehicles driven by the ugliest, most inconsiderate and aggressive drivers, who are usually talking on cell phones as they cut people off in order to get just 20 stupid feet ahead in a traffic jam, and I can think about how our children’s children will despise us for wasting all the future’s fuel and probably screwing up the climate, and how spoiled and stupid and disgusting we all are, and how it all just sucks …

If I choose to think this way, fine, lots of us do – except that thinking this way tends to be so easy and automatic it doesn’t have to be a choice. Thinking this way is my natural default setting. It’s the automatic, unconscious way that I experience the boring, frustrating, crowded parts of adult life when I’m operating on the automatic, unconscious belief that I am the centre of the world and that my immediate needs and feelings are what should determine the world’s priorities. The thing is that there are obviously different ways to think about these kinds of situations. In this traffic, all these vehicles stuck and idling in my way: it’s not impossible that some of these people in SUVs have been in horrible car accidents in the past and now find driving so traumatic that their therapist has all but ordered them to get a huge, heavy SUV so they can feel safe enough to drive; or that the Hummer that just cut me off is maybe being driven by a father whose little child is hurt or sick in the seat next to him, and he’s trying to rush to the hospital, and he’s in a much bigger, more legitimate hurry than I am – it is actually I who am in his way.

Again, please don’t think that I’m giving you moral advice, or that I’m saying you’re “supposed to” think this way, or that anyone expects you to just automatically do it, because it’s hard, it takes will and mental effort, and if you’re like me, some days you won’t be able to do it, or you just flat-out won’t want to. But most days, if you’re aware enough to give yourself a choice, you can choose to look differently at this fat, dead-eyed, over-made-up lady who just screamed at her little child in the checkout line – maybe she’s not usually like this; maybe she’s been up three straight nights holding the hand of her husband who’s dying of bone cancer, or maybe this very lady is the low-wage clerk at the Motor Vehicles Dept who just yesterday helped your spouse resolve a nightmarish red-tape problem through some small act of bureaucratic kindness. Of course, none of this is likely, but it’s also not impossible – it just depends on what you want to consider. If you’re automatically sure that you know what reality is and who and what is really important – if you want to operate on your default setting – then you, like me, will not consider possibilities that aren’t pointless and annoying. But if you’ve really learned how to think, how to pay attention, then you will know you have other options. It will be within your power to experience a crowded, loud, slow, consumer-hell-type situation as not only meaningful but sacred, on fire with the same force that lit the stars – compassion, love, the sub-surface unity of all things. Not that that mystical stuff’s necessarily true: the only thing that’s capital-T True is that you get to decide how you’re going to try to see it. You get to consciously decide what has meaning and what doesn’t. You get to decide what to worship.

Because here’s something else that’s true. In the day-to-day trenches of adult life, there is no such thing as atheism. There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship. And an outstanding reason for choosing some sort of god or spiritual-type thing to worship – be it JC or Allah, be it Yahweh or the Wiccan mother-goddess or the Four Noble Truths or some infrangible set of ethical principles – is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive. If you worship money and things – if they are where you tap real meaning in life – then you will never have enough. Never feel you have enough. It’s the truth. Worship your own body and beauty and sexual allure and you will always feel ugly, and when time and age start showing, you will die a million deaths before they finally plant you. On one level, we all know this stuff already – it’s been codified as myths, proverbs, clichés, bromides, epigrams, parables: the skeleton of every great story. The trick is keeping the truth up front in daily consciousness. Worship power – you will feel weak and afraid, and you will need ever more power over others to keep the fear at bay. Worship your intellect, being seen as smart – you will end up feeling stupid, a fraud, always on the verge of being found out.

The insidious thing about these forms of worship is not that they’re evil or sinful; it is that they are unconscious. They are default settings. They’re the kind of worship you just gradually slip into, day after day, getting more and more selective about what you see and how you measure value without ever being fully aware that that’s what you’re doing. And the world will not discourage you from operating on your default settings, because the world of men and money and power hums along quite nicely on the fuel of fear and contempt and frustration and craving and the worship of self. Our own present culture has harnessed these forces in ways that have yielded extraordinary wealth and comfort and personal freedom. The freedom to be lords of our own tiny skull-sized kingdoms, alone at the centre of all creation. This kind of freedom has much to recommend it. But there are all different kinds of freedom, and the kind that is most precious you will not hear much talked about in the great outside world of winning and achieving and displaying. The really important kind of freedom involves attention, and awareness, and discipline, and effort, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them, over and over, in myriad petty little unsexy ways, every day. That is real freedom. The alternative is unconsciousness, the default setting, the “rat race” – the constant gnawing sense of having had and lost some infinite thing.

I know that this stuff probably doesn’t sound fun and breezy or grandly inspirational. What it is, so far as I can see, is the truth with a whole lot of rhetorical bullshit pared away. Obviously, you can think of it whatever you wish. But please don’t dismiss it as some finger-wagging Dr Laura sermon. None of this is about morality, or religion, or dogma, or big fancy questions of life after death. The capital-T Truth is about life before death. It is about making it to 30, or maybe 50, without wanting to shoot yourself in the head. It is about simple awareness – awareness of what is so real and essential, so hidden in plain sight all around us, that we have to keep reminding ourselves, over and over: “This is water, this is water.”

· Adapted from the commencement speech the author gave to a graduating class at Kenyon College, Ohio. First published on the Guardian website.

pj harvey interview (2011)

In this fascinating interview for Spinner, PJ Harvey describes the intensive process of anchoring down the words and forms of the songs in advance of recording her album, Let England Shake.

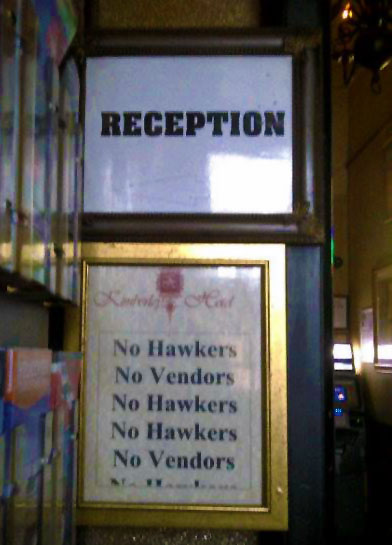

liberals at dusk (2005)

(Posted this first on Papanihil, a now-defunct blog I used to contribute to – on 29 June 2005)

“Oh C’MONNN!” The driver in front of me hesitates as the light turns orange. Rearing to a halt, I yank up the handbrake and a woman’s waddling over, a wad of Big Issues clamped under one armpit, a limp bundle slipping sleeping from its swaddling under the other. My window’s half-open.

In one deft movement she hikes up low-slung child with elbow, thrusts out magazine with hand. I shake my head, smiling blankly; she jerks hers toward the May issue lying on my back seat, barely visible in the failing light.

“Hey M’am, that one’s too much old now!”

“Sorry, at the moment I really don’t have any money, Sisi – see, I’m working as a volunteer. I’m not being paid this month.” It’s so bloody cold with the window down.

“Ohh, okay,” she shrugs, arching an eyebrow (what incredible co-ords), “I understand… You working for free.” Her words puff out, grey and laconic, a dragon’s exhausted fumes. She smiles. “Hawu. But you too stupid.”

I grin back, stupidly. “You’re right, hey.” The light’s about to change. “Okay, byebye now. Next month, I hope…”

She steps back, the car bucking forward as I take my sheepish foot off the clutch just a little too quickly. At least I had a valid excuse.

ella jara – phoenix of the sabbathi

This is a page taken from FLEURZINE, a zine curated and illustrated by Julia Mary Grey. You can go and download this beautiful work of art for free on her site, HERE.

The name was inspired by Fleurmach, and six pieces of writing from this blog appear in the publication. This piece is by Fleurmach contributor NoHolyCows.

i’m sorry i have to post this

TRIGGER WARNINGS: rape; lethal violence; murder.

I have just dreamed again of being Anene Booysen at the moment of her rape and immediately after it, my pooled blood congealing as my insides lie unseamed in the dust outside me, hacked apart from me, the jagged outside slammed inside me, in my last flickers of awareness the spasms of their hate ripping through me, thudding waves of blows, my head a heavy, dull explosion… the swirling, pulsing aftershocks of pain… going cold, knowing I can never be back together again, that I am smeared asunder into the ground like a fly or a cockroach or an ant, irreversibly crushed. It’s that final. I am no longer me, just a slowly drying patch of gore, beyond being gathered up and revived, soothed, cradled, stitched, kissed better, healed. No one can fix this, not my ma, not the hospital, not God. There is no “if” or “but”. I am aware that this is how I have ended.

I have no words strong enough to express the horror of this experience every time it happens to me, this dream. Yet I need to try to write it out of me in the hope that I never dream it again. Shhh, I tell myself, shivering uncontrollably, curled rigid and foetal, it was only a dream.

But it isn’t. This really happened. Really happens. Continues to happen. And that is what is most horrifying of all.

helen moffett on “women’s day” in 2013

“FUCK WOMEN’S DAY. FUCK IT.

Don’t ask me to celebrate Women’s Day. Don’t offer me ten percent off beauty products or a free glass of cheap bubbly. Don’t even ask me to commemorate the historic women’s march on the Union buildings – a milestone event whose noble essence has been sold down the river by leaders who are eager to claim some sort of retrospective credit for it, but don’t even pretend to honour its values.

Last year, I was in an epic rage. This year, I’m in despair.”

Read why Helen Moffett is so upset about this travesty of a public holiday HERE.

charles warnke on why you should date a girl who doesn’t read

You should date an illiterate girl.

You should date an illiterate girl.

Date a girl who doesn’t read. Find her in the weary squalor of a Midwestern bar. Find her in the smoke, drunken sweat, and varicolored light of an upscale nightclub. Wherever you find her, find her smiling. Make sure that it lingers when the people that are talking to her look away. Engage her with unsentimental trivialities. Use pick-up lines and laugh inwardly. Take her outside when the night overstays its welcome. Ignore the palpable weight of fatigue. Kiss her in the rain under the weak glow of a streetlamp because you’ve seen it in a film. Remark at its lack of significance. Take her to your apartment. Dispatch with making love. Fuck her.

Let the anxious contract you’ve unwittingly written evolve slowly and uncomfortably into a relationship. Find shared interests and common ground like sushi and folk music. Build an impenetrable bastion upon that ground. Make it sacred. Retreat into it every time the air gets stale or the evenings too long. Talk about nothing of significance. Do little thinking. Let the months pass unnoticed. Ask her to move in. Let her decorate. Get into fights about inconsequential things like how the fucking shower curtain needs to be closed so that it doesn’t fucking collect mold. Let a year pass unnoticed. Begin to notice.

Figure that you should probably get married because you will have wasted a lot of time otherwise. Take her to dinner on the forty-fifth floor at a restaurant far beyond your means. Make sure there is a beautiful view of the city. Sheepishly ask a waiter to bring her a glass of champagne with a modest ring in it. When she notices, propose to her with all of the enthusiasm and sincerity you can muster. Do not be overly concerned if you feel your heart leap through a pane of sheet glass. For that matter, do not be overly concerned if you cannot feel it at all. If there is applause, let it stagnate. If she cries, smile as if you’ve never been happier. If she doesn’t, smile all the same.

Let the years pass unnoticed. Get a career, not a job. Buy a house. Have two striking children. Try to raise them well. Fail frequently. Lapse into a bored indifference. Lapse into an indifferent sadness. Have a mid-life crisis. Grow old. Wonder at your lack of achievement. Feel sometimes contented, but mostly vacant and ethereal. Feel, during walks, as if you might never return or as if you might blow away on the wind. Contract a terminal illness. Die, but only after you observe that the girl who didn’t read never made your heart oscillate with any significant passion, that no one will write the story of your lives, and that she will die, too, with only a mild and tempered regret that nothing ever came of her capacity to love.

Do those things, damnit, because nothing sucks worse than a girl who reads. Do it, I say, because a life in purgatory is better than a life in hell. Do it, because a girl who reads possesses a vocabulary that can describe that amorphous discontent of a life unfulfilled—a vocabulary that parses the innate beauty of the world and makes it an accessible necessity instead of an alien wonder. A girl who reads lays claim to a vocabulary that distinguishes between the specious and soulless rhetoric of someone who cannot love her, and the inarticulate desperation of someone who loves her too much. A vocabulary, goddamnit, that makes my vacuous sophistry a cheap trick.

Do it, because a girl who reads understands syntax. Literature has taught her that moments of tenderness come in sporadic but knowable intervals. A girl who reads knows that life is not planar; she knows, and rightly demands, that the ebb comes along with the flow of disappointment. A girl who has read up on her syntax senses the irregular pauses—the hesitation of breath—endemic to a lie. A girl who reads perceives the difference between a parenthetical moment of anger and the entrenched habits of someone whose bitter cynicism will run on, run on well past any point of reason, or purpose, run on far after she has packed a suitcase and said a reluctant goodbye and she has decided that I am an ellipsis and not a period and run on and run on. Syntax that knows the rhythm and cadence of a life well lived.

Date a girl who doesn’t read because the girl who reads knows the importance of plot. She can trace out the demarcations of a prologue and the sharp ridges of a climax. She feels them in her skin. The girl who reads will be patient with an intermission and expedite a denouement. But of all things, the girl who reads knows most the ineluctable significance of an end. She is comfortable with them. She has bid farewell to a thousand heroes with only a twinge of sadness.

Don’t date a girl who reads because girls who read are storytellers. You with the Joyce, you with the Nabokov, you with the Woolf. You there in the library, on the platform of the metro, you in the corner of the café, you in the window of your room. You, who make my life so goddamned difficult. The girl who reads has spun out the account of her life and it is bursting with meaning. She insists that her narratives are rich, her supporting cast colorful, and her typeface bold. You, the girl who reads, make me want to be everything that I am not. But I am weak and I will fail you, because you have dreamed, properly, of someone who is better than I am. You will not accept the life of which I spoke at the beginning of this piece. You will accept nothing less than passion, and perfection, and a life worthy of being told. So out with you, girl who reads. Take the next southbound train and take your Hemingway with you. Or, perhaps, stay and save my life.*

*NOTE: Instead of the brave note on which the last sentence of the above version shared with me by Mavis Vermaak ends, the original text I googled when looking to credit the author correctly has as its ending the following two sentences:

“I hate you. I really, really, really hate you.”

montaigne on goody-two-shoeses

“There is no man so good, who, were he to submit all his thoughts and actions to the laws, would not deserve hanging ten times in his life.”

— Michel de Montaigne, essayist (1533-1592)

bifo berardi on how to act now

I must act “as if”. As if the forces of labour and knowledge may overcome the forces of greed and of proprietary obsession. As if the cognitive workers may overcome the fractalisation of their life and intelligence, and give birth to a process of the self-organisation of collective knowledge. I must resist simply because I cannot know what will happen after the future, and I must preserve the consciousness and sensibility of social solidarity, of human empathy, of gratuitous activity, of freedom, equality and fraternity. Just in case, right? Just because we don’t know what is going to be happening next, in the empty space that comes after the future of modernity. I must resist because this is the only way to be in peace with my self.

— Franco “Bifo” Berardi, from After the Future

bataille on the insubordination of material facts

Human life, distinct from juridical existence, existing as it does on a globe isolated in celestial space, from night to day and from one country to another—human life cannot in any way be limited to the closed systems assigned to it by reasonable conceptions. The immense travail of recklessness, discharge, and upheaval that constitutes life could be expressed by stating that life starts with the deficit of these systems; at least what it allows in the way of order and reserve has meaning only from the moment when the ordered and reserved forces liberate and lose themselves for ends that cannot be subordinated to any thing one can account for. It is only by such insubordination—even if it is impoverished—that the human race ceases to be isolated in the unconditional splendour of material things.

― Georges Bataille, from The Notion of Expenditure

further materials toward a theory of the man-child

In some cases, anonymity itself, which was supposed to express solidarity, abets sexism. Take Tiqqun. Founded in the late 1990s and dissolved after the 9/11 attacks, the French journal of radical philosophy attracted media attention when one of its founders, Julien Coupat, was arrested in November 2008 in connection with plans to sabotage the TGV train lines.

Semiotext(e) published translations of Tiqqun’s Introduction to Civil War and This is Not a Program between 2009 and 2011, and the anarchist press Little Black Cart books distributed Tiqqun 1 and Theory of Bloom in 2011 and 2012. Though their cops-and-robbers bombast sometimes raised our eyebrows, we read these with interest. Then, late last year, Semiotext(e) put out its next Tiqqun installment. Enclosed in a bright pink cover, and bookended with what looked like low-grade xerox collages of glossy magazine ads and soft porn, Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl confirmed all that we had begun to suspect.

Theory of the Young-Girl opens with a 10-page excursus sketching the “total war” that contemporary capitalism wages against anyone who dares oppose it. Echoing the work of Michel Foucault and Gilles Deleuze, Tiqqun argues that capitalism compels individuals to internalize its imperatives to live (and thus consume) in certain ways. Because the entire conflict is invisible, Tiqqun professes that “rethinking the offensive for our side is a matter of making the battlefield manifest,” revealing the processes by which contemporary society compels us to commodify even our intimate lives. Where can they best expose the front lines where capitalism is waging its invisible war? The “Young-Girl,” a figure Tiqqun invents to play both the exemplary subject of and the agent reproducing this system.

Tiqqun claims it has lady members and seems eager to reassure us that it does not hate us. “Listen,” Tiqqun writes. “The Young-Girl is obviously not a gendered concept … The Young-Girl is simply the model citizen as redefined by consumer society.” When early 20th century capitalism realized that, to reproduce itself, it would have to colonize social life, it particularly targeted the spheres of “youth” and “femininity”: the young, because they needed and wanted things, and did not yet work; women, because they governed social reproduction, i.e., had and raised kids.

The majority of what follows consists of a Situationist-ish collage that, in a series of vacillating typefaces and font sizes, presents the Young-Girl as a scapegoat as much as a victim.

Deep down inside, the Young-Girl has the personality of a tampon: she exemplifies all of the appropriate indifference, all of the necessary coldness demanded by the conditions of metropolitan life.

In love more than anywhere else, the Young-Girl behaves like an accountant.

There isn’t room for two in the body of a Young-Girl.

It appears that all the concreteness of the world has taken refuge in the ass of the Young-Girl.

There are beings that give you the desire to die slowly before their eyes, but the Young-Girl only excites the desire to vanquish her, to take advantage of her.

Like the nice guy from your grad-school program who tries to cover up his hurt feelings by concocting a general theory that explains why he never got a text after his one-night stand, the book portrays the Young-Girl as vain, frivolous, and acquisitive. She serves the traditional female role of reproducing the population and social order, but here, the social order is corrupt. Therefore, Tiqqun suggests, their intervention requires an ironic performance of misogyny. The question remains: Why is misogyny their only option? And why are so many thoughtful people ready to accept that a layer of irony suffices to turns hateful language into the basis of a sound critique?

We believe that Tiqqun has mistaken its object. The real enigma of our age is not the Young-Girl, who, we submit, has been punished enough already for how commodity culture exploits her. It is, rather, her boyish critic. Forms of crypto- and not-so-crypto misogyny have proved startlingly persistent not just within the radical left but also in the bourgeois-left spheres of cultural production: the publishing world, the museum, and the humanities departments of liberal-arts universities. We propose that a particular type is responsible for perpetuating such bad behavior. Call him the Man-Child.

***

It is not that we cannot talk Tiqqun talk. Look:

The Man-Child has two moods: indecision, and entitlement to this indecisiveness.

The Man-Child tells a racist joke. It is not funny. It is the fact that the Man-Child said something racist that is.

The Man-Child wants you to know that you should not take him too seriously, except when you should. At any given moment, he wants to you to take him only as seriously as he wants to be taken. When he offends you, he was kidding. When he means it, he means it. What he says goes.

The Man-Child thinks the meaning of his statement inheres in his intentions, not in the effects of his language. He knows that speech-act theory is passé.

The Man-Child’s irony may be a part of a generational aversion to political risk: he would not call out a sexist or racist joke, for fear of sounding too earnest. Ironically, the Man-Child lives up to a stereotype about the men from the rom-coms he holds in contempt: he has a fear of commitment.

The Man-Child won’t break up with you, but will simply stop calling. He doesn’t want to seem like an asshole.

He tells you he would break up with his girlfriend, but they share a lease.

The Man-Child breaks up with you even though the two of you are not in a relationship. He cites his fear of settling down. You don’t want marriage, at least not with him, but he never thought to ask you.

The Man-Child can’t even commit to saying no.

Why are you crying? The Man-Child is just trying to be reasonable. This is his calm voice.

The Man-Child isn’t a player. Many a Man-Child lacks throw-down. He puts on a movie and never makes a move.

Is Hamlet the original Man-Child? No: the Romantics made him one.

Just as not all men are Man-Children, neither are all Man-Children men.

Lena Dunham may be living proof that the Man-Child is now equal opportunity. That is, the character she plays on Girls is. A real man-child would never get it together to get an HBO show. As we watch Hannah Horvath pull a splinter out of her ass, we wonder: Is this second-wave feminism? Or fourth? It is no accident that Judd Apatow wrote the scene. The mesh tank Dunham wears over bare tits is isomorphic with the dick joke.

The hipster and the douchebag may be subspecies of the genus Man-Child.

If the Man-Child could use his ironic sexism to build a new world, would you want to live in it? Would anyone?

***

We could go on like this. Others have. Since Theory of the Young-Girl appeared in France in the late 1990s, the Man-Child has wandered far afield from the barricades, turning up more and more often in the mainstream liberal press. When Hanna Rosin published her widely discussed Atlantic essay and subsequent book, The End of Men, proposing that “modern, postindustrial society is just better suited to women,” she inaugurated a genre. A spate of articles lamented how the “mancession” was discouraging even nice boys from fulfilling the roles traditionally expected of them—holding a job, taking girls on dinner dates, eventually choosing one to marry, outearn, beget kids with, etc.

“The End of Courtship,” which the New York Times ran in January, is exemplary. “It is not uncommon to walk into the hottest new West Village bistro on a Saturday night and find five smartly dressed young women dining together—the nearest man the waiter,” its author concludes. “Income equality, or superiority, for women muddles the old, male-dominated dating structure.” Meanwhile, an online panic-mongering industry thrives by offering more or less reactionary advice to female page-viewers about how to turn whatever romantic temp work comes their way into a long-term contract.

Mancession Lit portrays the Man-Child as pitiful, contrasting him with women who are well-adjusted and adult. But it rarely acknowledges the real question that this odd couple raises. Namely, are women better suited to the new economy because they are easier to exploit?

In the mid-1970s, Italian Marxist feminists attempted to integrate an account of “immaterial labor” into their critique of capitalist society. They argued that when a shop attendant smiles for a customer, or a teacher worries too much about her students, or a parent does housework, they perform real labor. No accident that their examples came from spheres traditionally occupied by women. Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt later used the phrase “affective labor” to describe the emotional exertion that white-collar jobs increasingly require. Employers in economically dominant countries now primarily demand “education, attitude, character, and ‘prosocial’ behavior.” When job listings ask for “a worker with a good attitude,” what they want, say Hardt and Negri, is a smile.

In the culture sector, economic precarity constantly reminds employees of their expendability and, therefore, the importance of their investing affect in their workplace. To gain even an unpaid internship or a barely paid entry-level position in journalism, publishing, museums, or higher education, dedication is a must. Many jobs that used to be meal tickets for starving artists are now considered covetable and require “love.” A college freshman recently told us: “I have a passion for marketing.” A journalist friend recounts how, when she was still in college, a magazine editor approached her at a party with the line: “Yo, you should be my intern.” We imagine her smiling, as if to flatter his delusion that there were any print-media jobs still worth sleeping your way into; in any case, she did get a gig there.

Women’s long history of performing work without its even being acknowledged as work, much less compensated fairly, may account for their relative success in today’s white-collar economy. This is, at least, the story of the heroine that the new Mancession Lit has created. Call her the Grown Woman. A perpetual-motion machine of uncomplaining labor, shuttling between her job and household tasks, the Grown Woman could not be more different from either fat-year brats like Carrie Bradshaw, or Judd Apatow’s lady Man-Children. The Grown Woman holds down her job and pays for her own dinner. The Grown Woman feels like a bad mom when she sees the crafts and organic snacks that other moms are posting on Pinterest. She wonders whether feminism lied to her, but knows she will inherit the earth. Could this be because she is better than the Man-Child at performing what current economic conditions demand? She is certainly more practiced. Who among us hasn’t faked it, if only to make him stop asking?

***

Tiqqun knows and says what the Lifestyle section does or cannot: Today the economy is feminizing everyone. That is, it puts more and more people of both genders in the traditionally female position of undertaking work that traditionally patriarchal institutions have pretended is a kind of personal service outside capital so that they do not have to pay for it. When affective relationships become part of work, we overinvest our economic life with erotic value. Hence, “passion for marketing.” Hence, “Like” after “Like” button letting you volunteer your time to help Facebook sell your information to advertisers with ever greater precision.

In the postindustrial era, work and leisure grow increasingly indistinguishable: We are all shop girls now. From this “feminization of the world,” Tiqqun writes, “one can only expect the cunning promotion of all manner of servitudes.” At times, Tiqqun speaks of this exploitation sympathetically. More often, however, they blame the Young-Girl for opening the floodgates by complying with her own exploitation, thus making it easier for control capitalism to make her attitude compulsory for everyone.

Though its anxieties are of the moment, Tiqqun lifts its language from a long intellectual tradition that uses “woman” as shorthand. You can trace this line to Goethe’s Faust and the “eternal feminine” or Friedrich Schiller’s “Veiled Statue at Sais,” where “a youth, impelled by a burning thirst for knowledge,” pokes around Egypt looking for a busty sculpture of Isis that he calls “Truth.” Nietzsche continues using “woman” as a metaphor for the metaphysical essence that philosophers looked for beneath the surface of mere existence. But he borrows the language of his predecessors only to show how their quest failed—proposing, for instance, in Human, All Too Human that “women, however you may search them, prove to have no content but are purely masks.” Nietzsche’s point is that the woman called Truth was always already a cocktease: Nothing except existence exists.

Tiqqun offers an edgy update to such misogynist metaphors deployed for the purposes of demystification. At times, it speaks longingly of women who have not been utterly corrupted by capitalism. But when it learns what it knew all along—there is no outside; all human relationships have become reified—its disappointment at finding no one authentic to grow old with intensifies its vitriol. “It wasn’t until the Young-Girl appeared that one could concretely experience what it means to ‘fuck,’ that is, to fuck someone without fucking anyone in particular. Because to fuck a being that is really so abstract, so utterly interchangeable, is to fuck in the absolute.” Tiqqun’s language may be obscene, but its point is nothing new. The failure to see women as “anyone in particular,” or as subjects endowed with their own ends, has allowed men to fuck women over for centuries.

Read the rest of this incisive article HERE.

trancescript

before my lack of words

am I under your spelling

unformed

your words

write me out

uniformed

regimented

rote

do you read me

de-scribed

written off

declaimed

b e y o n d y o u r p r o n o u n c e m e n t s

i remain

uninformed

unsigned

do you read me

do you feel meta now?

Thanks to Michelle for this.

Thanks to Michelle for this.

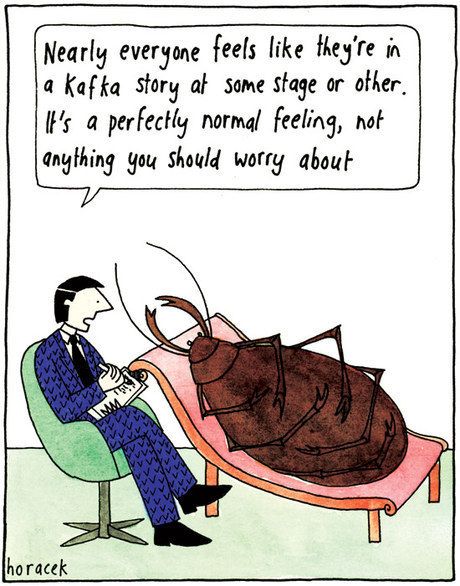

franz kafka on books worth reading

“I think we ought to read only the kind of books that wound and stab us. If the book we are reading doesn’t wake us up with a blow on the head, what are we reading it for? …We need the books that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone, like a suicide. A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us.”

— Franz Kafka

an open letter to barack obama

… On the occasion of his 2013 visit to South Africa

From Andile Lungisa, president of the Panafrican Youth Union

Dear Mr Obama,

Your election as the first President of the United States of America of African ancestry aroused immeasurable passions among the great multitude in our continent and around the world. The forlorn hope was premised on the retrospectively foolish idea that because your forebears were of those who had been dehumanized, hunted, captured, brutalized and ‘civilized’ throughout history, your leadership of the sole hyper-power on the planet would usher a period of decency, respect of human life, justice and peace.

Listening to your ‘Hopey’ enunciations, our people believed that the God of the dispossessed, tyrannized and abandoned had at last heard their raw and enduring prayers and had raised a son of their seed to redeem their humanity and medicate their future. On the 27th of November 2008, the day of your election, we cried and danced in the slums of Nairobi, the barrios of Caracas, ghettos of Detroit, gutters of Khayelitsha, hell zones of Cite Soleil, the brutally occupied territories of Palestine, in Manshiet Nasser of Cairo, in the shanty towns of Mumbai, the Al Qaryahs of Bayda, and in the many wastelands around the globe. Your election, which was energized by the young people of the United States, we were convinced, was a repudiation of the callousness, force, contempt and criminality with which the powerful from the industrialized West treated the majority of men. More importantly we hoped your victory signalled the beginning of the end of the 500 year war that the West has waged against the rest of humankind.

The oratory subterfuge notwithstanding, your presidency, Mr Obama, has been a geyser of gunk, incessant deceit and vacuity. Not only have you inherited the boorish and fantastical logic of imperial grandiosity, but you have embellished it to frightening heights. In an attempt to arrest the terminal historic decline of the US’ global hegemony and retain its position as the gendarme of capital accumulation, you have cultivated and harnessed an infrastructure of control, domination, death and destruction and thus ensuring a brutal future for the majority of humanity. In a delicious irony, tragic-comic in proportion, Lady History has elected you Mr Obama, a lawman by trade of African descent, to preside over the systematic defiling of the rule of law, and in turn magnify the death of a democratic consciousness and ascendance of thuggery among the ruling elites in the West.

Your administration has overseen a historic transfer of wealth from the public to the rapacious banksters to whom you are beholden. You have exhibited cold indifference, save for the empty rhetorical platitudes, to the most serious job crisis since the Great Depression, which has devastated especially African American communities, and left millions in destitution. You have intensified the hunting of the Black liberation revolutionary, Assata Shakur, who sought refuge in Cuba in 1979, escaping from the racist American industrial gulag that disproportionately incarcerates Black and Hispanic youths.

In your sanctimonious lecturing, please tell the young people at the University of Johannesburg why you ordered the murder of the 16 year old, Abdulrahman al Alawaki. Better yet, advise them on the rationale for a former teacher of law to grant himself the right to secretly kill his own citizens and anyone else the corporate-industrial police state deems a ‘terrorist’. Mr Obama, exhibit some moral probity, not your strong suit I know, in front of the young, impressionable minds you will be addressing and express some remorse for the thousands of women and children that you have killed and injured in your ‘signature’ drone strikes.

Tell the young people why Bradley Manning, a real American hero, who exposed the true and ugly face of American militarism and criminality, has been arrested and treated in a ‘cruel and inhumane’ manner according to the United Nations, whilst those whom he exposed continue to live in impunity. The ‘humanitarian’ industrial violence you discharged on the then sovereign state of Libya, which you don’t consider to have been a war, because no American soldier died, has unleashed a racist pogrom against Black Africans by your ‘freedom fighters’. Any word for the victims of your liberators, Mr Obama?

Under your presidency, and largely because of the unforgivable stupidity of African leadership in this generation, the American empire is building the infrastructure for AFRICOM military command – a feat that your buffoonish predecessor could not achieve. You’ve continued aiding and abetting the Zionist criminal enterprise against the Palestinians. The apartheid state of Israel, which Archbishop Tutu deemed more egregious than apartheid South Africa, kills Palestinian children with weapons supplied by your administration.

You, Mr Obama, son of a Kenyan father, are no different from the Bantustan leaders that we had in this country, and no amount of lyrical gymnastics will change the facts of your presidency.

luce irigaray – women on the market

Chapter Eight from This Sex Which Is Not One, 1985. This text was originally published as “Le marche des femmes,” in Sessualita e politica, (Milan: Feltrinelli, 1978).

The society we know, our own culture, is based upon the exchange of women. Without the exchange of women, we are told, we would fall back into the anarchy (?) of the natural world, the randomness (?) of the animal kingdom. The passage into the social order, into the symbolic order, into order as such, is assured by the fact that men, or groups of men, circulate women among themselves, according to a rule known as the incest taboo.

Whatever familial form this prohibition may take in a given state of society, its signification has a much broader impact. It assures the foundation of the economic, social, and cultural order that has been ours for centuries.

Why exchange women? Because they are “scarce [commodities] . . . essential to the life of the group,” the anthropologist tells us.1 Why this characteristic of scarcity, given the biological equilibrium between male and female births? Because the “deep polygamous tendency, which exists among all men, always makes the number of available women seem insufficient. Let us add that even if there were as many women as men, these women would not be equally desirable … and that, by definition. . ., the most desirable women must form a minority. “2

Are men all equally desirable? Do women have no tendency toward polygamy? The good anthropologist does not raise such questions. A fortiori: why are men not objects of exchange among women? It is because women’s bodies – through their use, consumption, and circulation – provide for the condition making social life and culture possible, although they remain an unknown “infrastructure” of the elaboration of that social life and culture. The exploitation of the matter that has been sexualized female is so integral a part of our sociocultural horizon that there is no way to interpret it except within this horizon.

In still other words: all the systems of exchange that organize patriarchal societies and all the modalities of productive work that are recognized, valued, and rewarded in these societies are men’s business. The production of women, signs, and commodities is always referred back to men (when a man buys a girl, he “pays” the father or the brother, not the mother … ), and they always pass from one man to another, from one group of men to another. The work force is thus always assumed to be masculine, and “products” are objects to be used, objects of transaction among men alone.

Which means that the possibility of our social life, of our culture, depends upon a ho(m)mo-sexual monopoly? The law that orders our society is the exclusive valorization of men’s needs/desires, of exchanges among men. What the anthropologist calls the passage from nature to culture thus amounts to the institution of the reign of hom(m)o-sexuality. Not in an “immediate” practice, but in its “social” mediation. From this point on, patriarchal societies might be interpreted as societies functioning in the mode of “semblance.” The value of symbolic and imaginary productions is superimposed upon, and even substituted for, the value of relations of material, natural, and corporal (re)production.

From “The Sensualist”, Kōshoku Ichidai Otoko’s animated interpretation of the 17th century novel by Ihara Seikaku

In this new matrix of History, in which man begets man as his own likeness, wives, daughters, and sisters have value only in that they serve as the possibility of, and potential benefit in, relations among men. The use of and traffic in women subtend and uphold the reign of masculine hom(m)o-sexuality, even while they maintain that hom(m)o-sexuality in speculations, mirror games, identifications, and more or less rivalrous appropriations, which defer its real practice. Reigning everywhere, although prohibited in practice, hom(m)o-sexuality is played out through the bodies of women, matter, or sign, and heterosexuality has been up to now just an alibi for the smooth workings of man’s relations with himself, of relations among men.

Whose “sociocultural endogamy” excludes the participation of that other, so foreign to the social order: woman. Exogamy doubtless requires that one leave one’s family, tribe, or clan, in order to make alliances. All the same, it does not tolerate marriage with populations that are too far away, too far removed from the prevailing cultural rules. A sociocultural endogamy would thus forbid commerce with women. Men make commerce of them, but they do not enter into any exchanges with them. Is this perhaps all the more true because exogamy is an economic issue, perhaps even subtends economy as such? The exchange of women as goods accompanies and stimulates exchanges of other “wealth” among groups of men. The economy in both the narrow and the broad sense-that is in place in our societies thus requires that women lend themselves to alienation in consumption, and to exchanges in which they do not participate, and that men be exempt from being used and circulated like commodities.

*

Marx’s analysis of commodities as the elementary form of capitalist wealth can thus be understood as an interpretation of the status of woman in so-called partriarchal societies. The organization of such societies, and the operation of the symbolic system on which this organization is based-a symbolic system whose instrument and representative is the proper name: the name of the father, the name of God-contain in a nuclear form the developments that Marx defines as characteristic of a capitalist regime: the submission of “nature” to a “labor” on the part of men who thus constitute “nature” as use value and exchange value; the division of labor among private producer-owners who exchange their women-commodities among themselves, but also among producers and exploiters or exploitees of the social order; the standardization of women according to proper names that determine their equivalences; a tendency to accumulate wealth, that is, a tendency for the representatives of the most “proper” names-the leaders-to capitalize more women than the others; a progression of the social work of the symbolic toward greater and greater abstraction; and so forth.

To be sure, the means of production have evolved, new techniques have been developed, but it does seem that as soon as the father-man was assured of his reproductive power and had marked his products with his name, that is, from the very origin of private property and the patriarchal family, social exploitation occurred. In other words, all the social regimes of “History” are based upon the exploitation of one “class” of producers, namely, women. Whose reproductive use value (reproductive of children and of the labor force) and whose constitution as exchange value underwrite the symbolic order as such, without any compensation in kind going to them for that “work.” For such compensation would imply a double system of exchange, that is, a shattering of the monopolization of the proper name (and of what it signifies as appropriative power) by father-men.

Thus the social body would be redistributed into producer-subjects no longer functioning as commodities because they provided the standard of value for commodities, and into commodity objects that ensured the circulation of exchange without participating in it as subjects.

*

Let us now reconsider a few points (3) in Marx’s analysis of value that seem to describe the social status of women.

Wealth amounts to a subordination of the use of things to their accumulation. Then would the way women are used matter less than their number? The possession of a woman is certainly indispensable to man for the reproductive use value that she represents; but what he desires is to have them all. To “accumulate” them, to be able to count off his conquests, seductions, possessions, both sequentially and cumulatively, as measure or standard(s).

All but one? For if the series could be closed, value might well lie, as Marx says, in the relation among them rather than in the relation to a standard that remains external to them – whether gold or phallus.

The use made of women is thus of less value than their appropriation one by one. And their “usefulness” is not what counts the most. Woman’s price is not determined by the “properties” of her body-although her body constitutes the material support of that price.

But when women are exchanged, woman’s body must be treated as an abstraction. The exchange operation cannot take place in terms of some intrinsic, immanent value of the commodity.

It can only come about when two objects-two women are in a relation of equality with a third term that is neither the one nor the other. It is thus not as “women” that they are exchanged, but as women reduced to some common feature-their current price in gold, or phalluses-and of which they would represent a plus or minus quantity. Not a plus or a minus of feminine qualities, obviously. Since these qualities are abandoned in the long run to the needs of the consumer, woman has value on the market by virtue of one single quality: that of being a product of man’s “labor.”

On this basis, each one looks exactly like every other. They all have the same phantom-like reality. Metamorphosed in identical sublimations, samples of the same indistinguishable work, all these objects now manifest just one thing, namely, that in their production a force of human labor has been expended, that labor has accumulated in them. In their role as crystals of that common social substance, they are deemed to have value.

As commodities, women are thus two things at once: utilitarian objects and bearers of value. “They manifest themselves therefore as commodities, or have the form of commodities, only in so far as they have two forms, a physical or natural form, and a value form” (p. 55).

But “the reality of the value of commodities differs in respect from Dame Quickly, that we don’t know ‘where to have it”’ (ibid.). Woman, object of exchange, differs from woman, use value, in that one doesn’t know how to take (hold of) her, for since “the value of commodities is the very opposite of the coarse materiality of their substance, not an atom of matter enters into its composition. Turn and examine a single commodity, by itself, as we will. Yet in so far as it remains an object of value, it seems impossible to grasp it” (ibid.). The value of a woman always escapes: black continent, hole in the symbolic, breach in discourse . . . It is only in the operation of exchange among women that something of this-something enigmatic, to be sure-can be felt. Woman thus has value only in that she can be exchanged. In the passage from one to the other, something else finally exists beside the possible utility of the “coarseness” of her body. But this value is not found, is not recaptured, in her. It is only her measurement against a third term that remains external to her, and that makes it possible to compare her with another woman, that permits her to have a relation to another commodity in terms of an equivalence that remains foreign to both.

Women-as-commodities are thus subject to a schism that divides them into the categories of usefulness and exchange value; into matter-body and an envelope that is precious but impenetrable, ungraspable, and not susceptible to appropriation by women themselves; into private use and social use.

In order to have a relative value, a commodity has to be confronted with another commodity that serves as its equivalent.

Its value is never found to lie within itself And the fact that it is worth more or less is not its own doing but comes from that to which it may be equivalent. Its value is transcendent to itself, super-natural, ek-static.

In other words, for the commodity, there is no mirror that copies it so that it may be at once itself and its “own” reflection. One commodity cannot be mirrored in another, as man is mirrored in his fellow man. For when we are dealing with commodities the self-same, mirrored, is not “its” own likeness, contains nothing of its properties, its qualities, its “skin and hair.” The likeness here is only a measure expressing the fabricated character of the commodity, its trans-formation by man’s (social, symbolic) “labor.” The mirror that envelops and paralyzes the commodity specularizes, speculates (on) man’s “labor.” Commodities, women, are a mirror of value of and for man. In order to serve as such, they give up their bodies to men as the supporting material of specularization, of speculation. They yield to him their natural and social value as a locus of imprints, marks, and mirage of his activity.

Commodities among themselves are thus not equal, nor alike, nor different. They only become so when they are compared by and for man. And the prosopopoeia of the relation of commodities among themselves is a projection through which producers exchangers make them reenact before their eyes their operations of specula(riza)tion. Forgetting that in order to reflect (oneself), to speculate (oneself), it is necessary to be a “subject,” and that matter can serve as a support for speculation but cannot itself speculate in any way.

Thus, starting with the simplest relation of equivalence between commodities, starting with the possible exchange of women, the entire enigma of the money form-of the phallic function-is implied. That is, the appropriation-disappropriation by man, for man, of nature and its productive forces, insofar as a certain mirror now divides and travesties both nature and labor. Man endows the commodities he produces with a narcissism that blurs the seriousness of utility, of use.

Desire, as soon as there is exchange, “perverts” need. But that perversion will be attributed to commodities and to their alleged relations. Whereas they can have no relationships except from the perspective of speculating third parties.