“It is no measure of health to be well-adjusted to a profoundly sick society.”

~ Jiddu Krishnamurti

“It is no measure of health to be well-adjusted to a profoundly sick society.”

~ Jiddu Krishnamurti

Studio album, released in 1970

Tracks

1. Baby night (16:24)

2. Silly Sally (16:22)

Total Time: 32:46

Musicians

– Andrew Dershin / bass

– Jay Dorfman / drums, percussion

– Marvin Kaminowitz / lead guitar, vocals

– Michael Paris / tenor saxophone, alto recorder, vocals, percussion

– Steve Rosenstein / rhythm guitar, vocals

Release information

LP EMI/Electrola 1C 064-28886 / LP EMI/Electrola 1C 062-28886 / LP EMI/Harvest 054-24311 / CD EMI CDP 538-7 48871 (1990)

Fire in My Belly (1987): David Wojnarowicz

Music: Diamanda Galas

Made by David Wojnarowicz for Rosa von Praunheim’s Silence = Death (1990).

A positive diagnosis for HIV in 1987 didn’t leave you with many options. The pharmaceuticals that have extended life spans for many of those now infected were not then available. Hostility and fear were rampant. It was reasonable to assume not only that you had received a death sentence, but that there was no hope on the horizon for those who, inevitably, would follow in your footsteps: an anguished decision to be tested, an excruciating wait for the results, a terrifying trip to the testing centre, and a life-shattering conversation with a grim-faced nurse or social worker.

Some turned to holistic medicine and yoga. Others to activism. Many just returned to their apartments, curled up in the corner, and waited to die.

But some, like David Wojnarowicz, who died in 1992 at the age of 37, used art to keep a grip on the world. He was the quintessential East Village figure, a bit of a loner, a bit crazy, ferociously brilliant and anarchic. He was a self-educated dropout who made art on garbage can lids, who painted inside the West Side piers where men met for anonymous sex, who pressed friends into lookout duty while he covered the walls of New York with graffiti. In 1987, his former lover and best friend, Peter Hujar, died of complications from AIDS, and Wojnarowicz learned that he, too, was infected with HIV.

Wojnarowicz, whose video A Fire in My Belly was removed from an exhibition of gay portraiture at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery last week after protests from a right-wing Catholic group and members of Congress, was an artist well before AIDS shattered his existence. But AIDS sharpened his anger, condensed his imagery and fueled his writing, which became at least as important as his visual work in the years before he died. In the video that has now been censored from the prominent and critically lauded exhibition Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture, Wojnarowicz perfectly captured a raw Gothic, rage-filled sensibility that defined a style of outsider art that was moving into the mainstream in the late 1980s.

It may feel excessive now, but like other classic examples of excessive art – Allen Ginsberg’s 1955 poem, Howl, Krzyzstof Penderecki’s 1960 symphonic work, Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima, or Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1975 film, Salo – it is an invaluable emotional snapshot. Not simply a cry of anguish or protest, Wojnarowicz’s work captures the contradiction, speed and phantasmagoria of a time when it was reasonable to assume that all the political and social progress gay people had achieved in the 1960s and ’70s was being revoked – against the surreal, Reagan-era backdrop of Morning in America, and a feel-good surge of American nostalgia and triumphalism.

Read more of this 2010 article by Philip Kennicott, from the Washington Post, HERE.

“Get to me and turn me well; I’m a tired soul.”

Album: Jewellery

Label: Rough Trade Records/Accidental

Video Director & Editor: Joan Guasch

“All that we know is nothing, we are merely crammed wastepaper baskets, unless we are in touch with that which laughs at all our knowing.”

– D H Lawrence

This poetic, surrealistic and disturbing Swedish film – sometimes called a “black comedy” – written and directed by Roy Andersson, received a number of awards, including the Swedish Film Critics Award and the Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival. It makes use of many quotations from the work of the Peruvian poet César Vallejo. It’s like a multiple pile-up where Vallejo is crashed into by Beckett, tail-ended by Bergman… and Monty Python can’t slow down or swerve enough to avoid sandwiching them all together.

Reviewed by Anton Bitel:

“Everything has its day,” says the CEO Lennart (Bengt CW Carlsson), concealed (but for his bare feet) beneath a sunbed, to his flustered sub-manager Pelle (Torbjörn Fahlström) in the opening scene of Roy Andersson’s Songs From The Second Floor. “This is a new day and age, Pelle – you have to realise that.” Faced with the imminent collapse of his business empire and the mass unemployment that will inevitably result, this invisible mogul has already decided to take the money and run, contemplating a better life (or should that be afterlife?) abroad for himself in the future once he has put the past behind him. With blithe disregard for those that he is abandoning, he asks, “What’s the point of staying where there is only misery?” – and yet Andersson’s film offers a dystopian vision of the new millennium, where misery, pain, guilt and despair are the universal condition, where escape is impossible, and where, no matter how much anyone tries to turn their back on the past, somehow it always returns.

If everything has its day, the Songs From The Second Floor was certainly a long time in coming. Andersson first discovered the avant-garde Peruvian poet César Vallejo (19892-1938) back in 1965, and first read his poem Stumble Between Two Stars while working on his second feature Gilliap (1975). In the early Eighties he began preparations for a documentary feature based around the poem, before concluding that the material would be better served by the medium of fiction. So he established an independent film studio in 1981, and devoted the next 15 years of work (in short films and commercials) to inventing and honing an aesthetic style that would make his unique vision for this third feature possible. Production proper began in 1996, and lasted four long years – but the results were well worth the wait, and would indeed win the Swedish writer/director a slew of international awards.

The film is told in a series of stylised, hyperreal tableaux, unfolding in indifferent wideshot before an unmoving camera whose very distance helps convert all the tragedy of human experience on display into a very singular brand of dark comedy. Hence the mannered grey makeup worn by the performers – for while this may reflect their status as spiritual zombies lost to their own moral damnation, it is also the familiar mask of clowns, and all these characters are both the living dead and comic chumps. So it is that when, in one sequence, a stage magician (Lucio Vucina) accidentally saws into the belly of his hapless volunteer (Per Jörnelius), eliciting immediate cries of pain, we share the fictive audience’s initial instinct to laugh, even as we are horrified.

Some of the film’s episodes are self-contained vignettes, while others feature an ensemble of recurring characters in the orbit of Kalle (Lars Nordh). Having just torched his own furniture business, this corpulent, middle-aged salesman must deal with sceptical insurance adjusters and find a new outlet (viz. crucifixes) for his flagging spirit of entrepreneurship, even as a strong sense of guilt, both personal and collective, keeps creeping up on him.

Meanwhile Kalle’s eldest son, the poet Thomas (Peter Roth), suffers in silence in a mental institution, leaving his sensitive younger brother Stefan (Stefan Larsson) to pick up the pieces and hear the depressed confessions of passengers in his taxi cab. In the background of all this grief and anxiety, Andersson reveals a grimly absurd vista of societal breakdown, where acts of racist violence go unchecked, traffic jams go on forever, suited flagellants mortify themselves in the street, the dead walk among the (almost) living, panicking financiers resort to crystal balls, and a virgin is publicly sacrificed in a last-ditch effort to fend off not just economic ruin but the end of days.

“Beloved be the ones who sit down,” reads on-screen text near the beginning of Songs From The Second Floor, cited from Vallejo’s Stumble Between Two Stars – and it will recur, along with other lines from the poem, several times within the film itself. At first there might seem little room for poetry in Andersson’s nightmarish picture of a venal, gloomy and bleakly prosaic metropolis whose only poet, Thomas, whether driven mad by his work or by the world, has been reduced to inarticulate muteness.

And yet, like the ghosts of the dead that continue to haunt Kalle’s heavy conscience, or like the buried Nazi past of the superannuated general (Nils-Åke Olsson) that resurfaces in a torrent of Tourette’s-style outbursts (à la Dr Strangelove), poetry just keeps coming back. Even in a setting as banal as a commuter train, Andersson’s drab characters are apt to burst into choral song (magisterially scored by none other than ABBA’s Benny Andersson).

Much of the film’s poetic humanism derives from the word ‘beloved’ that forms a refrain in Vallejo’s poem. For while Andersson may offer up a monstrous parade of vices and vulnerabilities, he invites us to love his gallery of rogues precisely for the flaws that make them – and all of us – so human. A key, repeating image in the film is of different characters perched on the end of their beds, making each and every one of them “the ones who sit down” – but it is a phrase that rather pointedly describes any viewer as well, ensconced in cinema or on sofa. After all, Andersson’s story of frailty and folly is our story too – and at the end of the extraordinary 10-minute single take that closes Songs From The Second Floor, the look that Kalle gives straight to camera implicates us all in the film’s haunting return of the repressed.

Put simply, the everyday apocalypse envisaged in Songs From The Second Floor is a wonder to behold, an idiosyncratic humanist allegory without parallel in cinema – unless, of course, you include Andersson’s equally astonishing follow-up You, The Living (2007), with which it forms the first two parts of a projected trilogy on the “inadequacy of man”.

Directed and written by: Roy Andersson

Director of Photography: István Borbás, Jesper Klevenås

Music: Benny Andersson

This review was first published HERE.

Trailer for the new Katinka Heyns film Die Wonderwerker, based on the life of poet, lawyer, naturalist and morphine addict, Eugene Marais.

Released: 7th September 2012

Starring: Cobus Rossouw, Marius Weyers, Sandra Kotze, Dawid Minnaar, Elize Cawood, Anneke Weidemann, Kaz McFadden, Erica Wessels

Synopsis:

Eugene Marais was not only a remarkable poet and naturalist, but an extraordinary person whose life was a continuous source of drama and controversy. In 1908, he is a qualified lawyer who has just spent a solitary 2 years living amongst the baboons of the remote Waterberg; studying their habits.

On his way to Nylstroom, in the grip of a Malaria induced fever, he stops on a farm looking for drinking water. Observing his weakness and the seriousness of his illness, Gys van Rooyen and his wife Maria take him into their home to recover.

Maria leads an unfulfilled life and she is lonely. The forty year old Eugene Marais is attractive, charming and mysterious. She, as many women before her, falls in love with him. There are two others resident in the house, the Van Rooyen’s son Adriaan, and a seventeen year old adopted daughter Jane Brayshaw.

Twelve years earlier Marais’ young wife, Aletta, died giving birth to their only child, something he was never able to process. Jane is a striking embodiment of her. Gradually he realizes he is losing his heart to her. And she reciprocates. What further complicates matters is that the young Adriaan is himself smitten with Jane.

Eugene Marais’ secret demon is his morphine addiction. He is a high functioning addict- whose behaviour is only affected when he doesn’t use it. Maria discovers his secret. In an attempt to not only curb his addiction but also to assert control over him, she confiscates his morphine and begins rationing it back to him.

This leads to a love quadrangle, like a time bomb ticking. Inevitably ticking…

This Film is in Afrikaans with English subtitles.

“There is no why for my making films. I just liked the twitters of the machine, and since it was an extension of painting for me, I tried it and loved it. In painting I never liked the staid and static, always looked for what would change the source of light and stance, using glitters, glass beads, luminous paint, so the camera was a natural for me to try—but how expensive!” – Marie Menken

16mm, color, sound, 4 min

Original score by Teiji Ito. “A new sound version of this classic. It is a beautiful experience to see her fabulous shooting. The cutting is just as fabulous and is something for all to study; the new score by Teiji Ito is ‘out of this world’ with its many-leveled instrumentation. Marie says ‘These animated observations of tiles and Moorish architecture were made as a thank-you to Kenneth for helping to shoot on another film in Spain.’ Shot in the Alhambra in one day.” – Gryphon Film Group

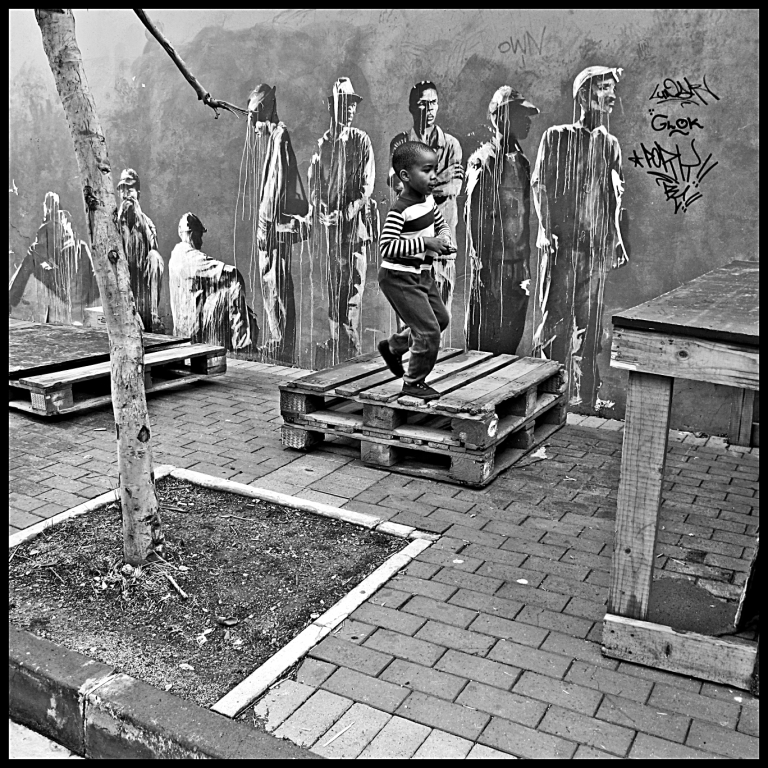

© Germaine de Larch Images. First published on http://www.life-writ-large.posterous.com

Street art by Faith47 (www.faith47.com)

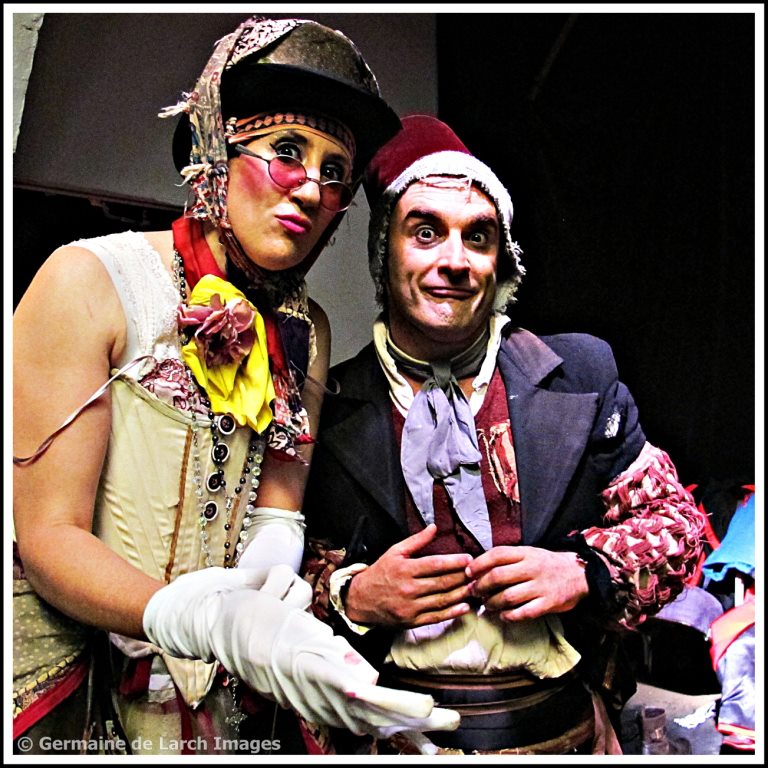

Patricia Boyer & Jason Kennett

© Germaine de Larch Images. First published on http://www.life-writ-large.posterous.com

‘He is on a journey, during the night, the end of which keeps receding. He has a sense of the danger, of the loss that the pseudo-object attracting him represents for him, but he cannot help taking the risk at the very moment he sets himself apart. And the more he strays, the more he is saved.’

– Julia Kristeva, 1982

“I think ahead of you… I think instead of you.”

Performed live, the disjointed conglomerate of sighing, stuttering samples becomes a sunny little menace on Later… with Jools Holland, 1996.

“I like your music very, very much, because you give space to the listener. He can go inside and live there. But a lot of music from the last few centuries, you just have to sit, and listen.”

Björk interviews Arvo Pärt for the BBC program ‘Modern Minimalists’ (1997).

Sometimes I wish I had a penis.

How much simpler it would make things!

We’d hang together,

free flowing,

without ration,

without suspicion,

without tourniquets

to cut off our blood

if it quickened

in each other’s presence.

It’s brutally,

uselessly,

PAINFUL

being confined to this

invisible,

plugged-up

box.

William S. Burroughs performing A Thanksgiving Prayer. (C) 1990 The Island Def Jam Music Group

las parcas 1 and 3 bromoil transfer on paper (1930)

from a triptych by Spanish photographer Joaquim Pla Janini (1879 – 1970) based on Les Parcae (the Fates).

Hello babies. Welcome to Earth. It’s hot in the summer and cold in the winter. It’s round and wet and crowded. On the outside, babies, you’ve got a hundred years here. There’s only one rule that I know of, babies ―”God damn it, you’ve got to be kind”.

― Kurt Vonnegut, from God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater

Don’t surrender your loneliness so quickly.

Let it cut more deeply.

Let it ferment and season you

as few humans and even divine ingredients can.

Something missing in my heart tonight

has made my eyes so soft,

my voice so tender,

my need for God absolutely clear.

~ Hāfez

Biographical note:

Khwāja Šams ud-Dīn Muhammad Hāfez-e Šīrāzī, or simply Hāfez (Persian: خواجه شمسالدین محمد حافظ شیرازی), was a Persian mystic and poet. He was born sometime between the years 1310 and 1337. John Payne, who has translated the Diwan Hafez, regards Hafez as one of the three greatest poets of the world. His lyrical poems, known as ghazals, are noted for their beauty and bring to fruition the love, mysticism, and early Sufi themes that had long pervaded Persian poetry. Moreover, his poetry possesses elements of modern surrealism.

US garage psych from 1966.

Based on the unfinished film by Henri George Clouzot, L’Enfer” (Inferno), with the beautiful Romy Schneider. Music by Lee Hazlewood.

Abîme… Abîme!

Tu as commis le pire des crimes

En faisant de Dieu

L’instrument de ta morsure.

Mon père s’est marié à deux reprises

Une fois à l’Est et une deuxième fois à l’Ouest… de Jérusalem…

Je suis palestinienne

Et ma demi- sœur est israélienne

On ne se parle plus…

Je parle arabe, elle parle hébreu

Mais on ne se comprend plus…

On fait semblant de ne plus se comprendre!

From HERE.

An improvisation with microphone, guitar effects pedal and bongos.

Turkish language version of the Roma song “Ederlezi”, made famous outside the Balkans via Goran Bregovic’s version in Emir Kusturica’s film, Time of the Gypsies.

The song got its name from Ederlezi (Turkish: Hıdırellez) which is a spring festival celebrated by Roma people in the Balkans, Turkey and elsewhere around the world.

From Wikipedia:

Hıdırellez or Hıdrellez (Turkish: Hıdrellez or Hıdırellez, Azerbaijani: Xıdır İlyas or Xıdır Nəbi, Crimean Tatar: Hıdırlez, Romani language: Ederlezi) is celebrated in Turkey and throughout the Turkic world as the day on which prophets Hızır (Al-Khidr) and Ilyas (Elijah) met on the earth. Hıdırellez starts on May 5 night and falls on May 6 in the Gregorian calendar and on April 23 in the Julian calendar. It celebrates the arrival of spring and is a religious holiday for the Alevi as well. Đurđevdan or the Feast of Saint George is the Christian variety of this spring festival celebrated throughout the Balkans, including Serbia and Bulgaria, notably in areas under the control of the Ottoman Empire by the end of the 16th century.

There are various theories about the origin of Hızır and Hıdırellez. Ceremonies and rituals were performed for various gods with the arrival of the spring or summer in Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Iran and other Mediterranean countries since ancient times. One widespread belief suggests that Hızır attained immortality by drinking the water of life. He often wanders the earth, especially in the spring, helping people in difficulty. People see him as a source of bounty and health, as the festival takes place in Spring, the time of new life.

English translation:

Spring has come,

I’ve tied a red pouch on a rose’s branch,

I’ve vowed a house with two rooms

In the name of a lover

The mountain is green, the branches are green

They’ve awakened for the bayram (festival day)

All hearts are happy

Only my fate is black

The scent of jonquils is everywhere,

It’s time.

This spring, I’m the only one

Whom the bayram has not affected

Don’t cry, Hıdrellez

Don’t cry for me

I’ve sowed pain, and instead of it,

Love will sprout, will sprout

In another spring.

He has neither a way (known) nor a trace

His face is not familiar

The long and short of it,

My wish from the God is love.

I don’t have anyone to love, I don’t have a partner

One more day has dawned.

O my star of luck,

Smile on me!

(Translation based on the one here; not sure how good it is!)