Here’s a thought piece I wrote for an MPhil African Studies class back in April, in the thick of the Rhodes Must Fall resistance. I want to put it here to archive it.

Problematising the Study Of Africa Assignment:

On Colonial Legacies at the University of Cape Town

—

“Remember that you are an Englishman, and have consequently won first prize in the lottery of life.” — Cecil John Rhodes[1]

“[N]o matter what a white man does, the colour of his skin—his passport to privilege—will always put him miles ahead of the black man. Thus in the ultimate analysis no white person can escape being part of the oppressor camp.” — Bantu Stephen Biko[2]

“For the black man there is only one destiny, and it is white.” — Frantz Fanon[3]

—

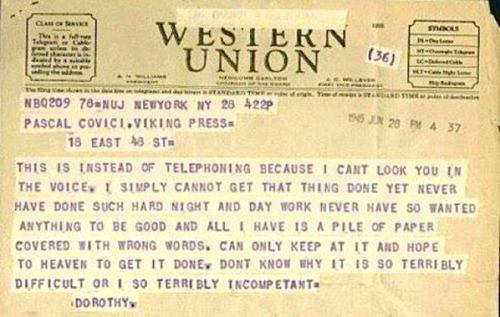

Rhodes statue, head covered in garbage bags. University of Cape Town, 17 March 2015. Photo: Rosemary Lombard

As a child, I remember reading about the railway Cecil John Rhodes envisioned from Cape Town to Cairo, and never imagining it in any light other than as a benevolent feat of engineering that would link people to others, bringing access to resources and the rest of the modern world for those cut off from Western civilisation, literally bringing light to the darkest parts of the continent.

I revised my romantic understanding of Rhodes’ expansionist desires as I became aware of the rampantly exploitative nature of these ambitions, and colonial mechanisms of dominion and exploitation more generally, but it was not until the recent events at UCT surrounding a statue of the man on campus that I realised the true psychological extent and durability of this oppressive colonial legacy, and the way its violence has been rendered almost invisible to those of us on the privileged side of what Walter Mignolo terms the “colonial difference” or divide[4].

The call for transformation is not new: it stretches back more than two decades. The present moment is notable in that students, staff and workers have organised powerfully in concert. A bucket of human excrement thrown on a statue of Rhodes that occupied a central position on UCT’s upper campus escalated tensions around institutional racism that have flared regularly since even before the formal end of the Apartheid era 21 years ago. Black students formed a movement that became known as “Rhodes Must Fall” (RMF) after the social media hashtag they used to mobilise. The students occupied an administrative building for several weeks, in which they held intensive teach-ins and discussions around decolonisation in solidarity with the Students’ Representative Council (SRC), other students, academic staff and workers. University management eventually capitulated to the removal of the statue on 9 April 2015, after a month-long struggle in which RMF demanded to be engaged on their own terms, rather than allowing university management to dictate the terms or to dismiss the protest as had been the case on many previous occasions.

Richard Pithouse describes the mobilisation thus:

The students in Cape Town have, very rapidly, punched a gaping hole into the continuum of English liberal hegemony over the university, and a set of linked sites of a certain kind of elite power, and, thereby, a mode of white supremacy and coloniality that has not been subject to sufficient critique and opposition. It is an extraordinary political achievement that will, no doubt, inscribe itself into the history of the South African academy, and the wider society.[5]

At this historically significant moment, it is on white liberal hegemony and institutional transformation at UCT that I reflect: how has hegemonic whiteness been constructed at UCT, and how does the university continue to function as a colonial space, despite speaking about transformation?

—

I have made several false starts on this assignment (one of which has been losing an entire day’s work on it due to a computer glitch). Initially my idea was to write an open letter to university management, particularly the deputy Vice-Chancellor with the portfolio for transformation, Crain Soudien, whose public behaviour over the past weeks – both in his capacity as a member of university management[6] and in his written statements in the press – has seemed at odds with his historically professed radical stance against uninterrogated hegemony, and his advocacy of deep transformation as chair of the country-wide Ministerial inquiry into institutional racism just a few years ago[7]. Soudien, and other prominent black members of the corporate, academic establishment such as Jonathan Jansen, are interpellated[8] representatives of their institutions’ ideology, and any hint of activism they once displayed has evaporated.

However, I decided that I could not, in good conscience, from my position as an historical beneficiary of the untransformed system, write such a letter. So, dropping the academic apparatus as prompted by this assignment, I feel I have only enough authority to write from a personal, situated angle in attempt to contextualise the recent Rhodes Must Fall chain of events at UCT, with particular reference to the institution’s persisting coloniality. I cannot assume anything other than my own subject position, as a white, cisgender, heterosexual female, who comes from relative privilege. To do so would be disingenuous, as I have learned a trenchant lesson through listening to what students have been saying these past weeks: despite my best intentions and all the empathy I can muster, I cannot have knowledge of what it is to experience institutional racism.

As a “white” person, I have ancestrally been on the powerful side of the racial divide put in place with the advent of Western colonial activity, and I continue to be identified with that subject position. “Whiteness” is the term used to describe the position of privilege this subjectivity puts me and others like me in.

If there is one thing the Rhodes Must Fall moment has driven home to me, it’s that from my subject position I am unqualified to make authoritative pronouncements regarding the experiences or motives of anyone except myself, regardless of racial identity: it’s obvious that I can’t speak to “black” experience, but the most common “white” responses to RMF have largely made me feel alienated, too.

Two decades of rainbow nation narrative have led to the unreflexive “I don’t see colour” rhetoric becoming the status quo among liberal-thinking white South Africans, as well as black people assimilated to corporate institutional capitalist ideology. This is pernicious in that it obscures the very real, material persistence of different life experiences and oppression based on inherited structural inequalities, stemming from racial discrimination.

Coloniality, the set of dispositions, values and forms of practice set in place in the colonial world, outlives the moment of formal political decolonisation, and carries through beyond it in lasting ways. The white Western self speaks from the site of the universal, as a bearer of modernity and civilisation, situated dynamically inside of linear time and at home in a global, cosmopolitan world. All forms of knowledge produced by the Western self, in other words, are deemed to have universal, rational, historical currency.

In contrast, those selves and forms of knowledge encountered by the Western self that are deemed to be other than the Western self are deemed to be “local”, labelled “indigenous”. An indigenous self or indigenous knowledge is constituted as static, standing outside of history and linear time, and inside of tradition, which becomes the opposed category to modernity. Western, colonial knowledge is framed in binaries, in relation to Western supremacy: the privileged poles of these dyads are whiteness, maleness, heterosexuality, and so forth.

Manichean power relationships instituted on the basis of the colonial apparatus did not end with apartheid in 1994. They persist throughout social interactions, their oppressive dynamics all but invisible to those on the privileged side of such relationships, such as white people and males, due to the hegemonic nature of this framing.

A common criticism I saw levelled at black protesters by white commenters was that things changed with the coming of the democratic dispensation in 1994, and that they should stop “holding on to the past” or “playing the race card” with a “victim mentality”, that they should “move on”. But being cognisant of how the legacy of chronologically past events persists into the present is not the same as “holding on to” the past. Only those who are not experiencing the continuation of structural oppression every day can advocate ignoring or disregarding it, and “moving swiftly on”.

Western knowledge systems condition us not to admit any other perspective to the realm of validity. It thus takes concerted effort from white people to listen and not dismiss other points of view if they are to “click” and be able to acknowledge that the hegemonic “white” point of view is not the only, natural point of view. Recognition of the persisting inequality and oppression of black people generates a sense of discomfort and cognitive dissonance. I have realised through conversations with white people I know, as well as the comments I’ve read on social media, that most are unwilling (or perhaps intellectually unable?) to make this effort. Most who identify as liberal (“colour-blind”, non-racist) do not want to accept that they continue to benefit from this system at the expense of others, and display great defensiveness when confronted with the persistence of structural racism, and white complicity therewith.

The comments I have seen by white people who consider themselves liberal and “non-racial” (strenuously disavowing racism) against protesters have been telling – describing them as “uncivilised”, “uneducated”, “unreasonable”, “backward”, “barbarians”, “savages”, “childish”, “monkeys”: these epithets bear the distinctive, unreflexive tang of colonial binaries, binaries set up in implied counterpoint to the opposite values ostensibly possessed by the hallowed university. These colonial tropes have pervaded media, misrepresenting Rhodes Must Fall as an unthinking, destructive mob, when the reality is that the movement created, in a deliberate and considered way, an autonomous space which has surfaced deep pain, but also fostered constructive discussion and reimaginative work.[9]

Acts of physical protest occur when speech has failed, or is perceived to be inadequate. The act of flinging sewage at the statue of Rhodes went beyond talking, because talking was no longer believed to be a viable option for engaging. For dialogue to happen, there needs to be a willingness to listen communicated clearly. UCT, and whiteness more generally, has historically demonstrated itself to be dismissive, unprepared to engage black students’ and staff’s grievances about structural oppression. UCT even went so far as to criminalise protesters.

Steven Friedman remarks:

It is no accident that the protests are happening on the campuses of English-speaking “liberal” universities, which have long claimed to be victims of racism: it is precisely at those institutions that race is kept alive by denying it. Under apartheid, many English-speaking whites insisted that apartheid was created by Afrikaners alone. The “liberal” English-language universities joined in — they proclaimed their right to teach whatever and whomever they pleased, declaring that discrimination was imposed on them by the state. This smugness ignored the extent to which white English speakers in the professions and business profited from the denial of opportunities to others — and the degree to which they believed that blacks could win acceptance only if they adopted the values of whites. The universities ignored the reality that, when they were allowed to do as they pleased, they limited black student numbers and taught courses that assumed that every South African was white… This shows how deep-rooted the attitudes that underpinned apartheid are — and it points a finger at a form of liberalism that has washed its hands of racism while continuing to practise it…

When democracy arrived, the legal barriers tumbled; deep-rooted beliefs that whites are superior did not. The “liberal” universities now had the right to teach who and what they pleased: they used it to keep alive the racial pecking order in a “colour blind” guise… Whites remain largely in charge — but, because they are “liberal”, they always have a good “nonracial” reason for why this should be so.[10]

Hegemonic white power is not always subtle. UCT management has an historical track record of overt institutional racism too. There are several junctures at which these issues have crystallised blatantly, and I will mention two:

In 1968, the accomplished black anthropologist, Archie Mafeje, was made an offer of employment by UCT, but this offer was rescinded under pressure from the Apartheid government, sparking protests. In 1991, the university again offered Mafeje a position. Although he had by that time, 23 years after the first offer, attained the rank of professor, it offered him only a senior lecturer post, still treating him as a junior academic. UCT apologised to Mafeje for this indignity after his death, naming a room in the Bremner building in his honour. It was no coincidence that this room was made the headquarters of Rhodes Must Fall when they occupied that building, renaming it “Azania House” in symbolic redress.

The so-called “Mamdani Affair” unfolded at UCT in 1996 when eminent Ugandan scholar Mahmood Mamdani, who at that point held the AC Jordan Chair in the Centre for African Studies, challenged the university to place African scholarship at the centre of the curriculum. He compiled a curriculum centred on African scholarship which was met with resistance from the all-white advisory committee, apparently because it did not reflect thinkers well-known enough to the committee – that is, it did not reproduce the established western canon of writing about Africa closely enough. Via a manipulation of administrative processes, the curriculum Mamdani planned was rejected and replaced by one produced by the committee. He was suspended and left UCT soon afterwards for the United States. Nomalanga Mkhize charges that the affair “exposed the ignorance of many prominent, predominantly white South African scholars who, because of their racially privileged positions, had risen up the ranks without having to engage three decades of rigorous post-independence African scholarship.”[11]

Black students and academics are angry. Twenty years since the formal end of apartheid, they are still treated as second-class citizens on campus. Only a fraction of teaching staff are black[12], and the syllabus overwhelmingly represents the perspectives of white thinkers. Black thinkers continue to be marginalised. The disciplines are still, overwhelmingly, epistemologically “white”. Francis Nyamnjoh, writing in 2012, describes the insidious outcome of this:

In Africa, the colonial conquest of Africans – body, mind and soul – has led to real or attempted epistemicide – the decimation or near complete killing and replacement of endogenous epistemologies with the epistemological paradigm of the conqueror. The result has been education through schools and other formal institutions of learning in Africa largely as a process of making infinite concessions to the outside – mainly the western world. Such education has tended to emphasize mimicry over creativity, and the idea that little worth learning about, even by Africans, can come from Africa. It champions static dichotomies and boundedness of cultural worlds and knowledge systems. It privileges teleology and analogy over creative negotiation by Africans of the multiple encounters, influences and perspectives evident throughout their continent. It thus impoverishes the complex realities of those it attracts or represses as students.[13]

A statement by UCT’s Student Representative Council, made at a meeting the day the statue was removed, echoes the points made above:

[T]he black folk’s problem is still chiefly the potency of whiteness. In the new democratic dispensation, we have only been concerned with the ‘rainbow nation’ rhetoric and singing kumbaya while our economy still reflects the same socio-economic disparities of the apartheid era. Democracy has granted a few blacks seats at the master’s table; the rest are still fighting over breadcrumbs falling off the table. And it is these few and mostly politically connected ‘privileged’ blacks who assist their white masters in maintaining the status quo.

Whites have not even begun to see blacks as equals and as being capable of thinking for themselves. They continually want to have a say in how we break the shackles of oppression administered and maintained by them. They cry foul as soon as blacks start organising and speaking for themselves. Deep down they understand that they stand to lose their privileges. The white liberal has continued to play a rather peculiar role in the oppression of the black masses, his racist and conservative ways continue to be shielded in his subtle and ‘angelic’ approach. It is the white liberal who is at the forefront of spreading the gospel of integration and a peaceful society. White liberals point towards white conservatives as the problem, and they have convinced themselves that they have arrived at enlightenment pertaining to the sins committed by their forefathers. Yet subconsciously they share the same set of values and desire to protect their privileges.

The ideology and culture of formerly ‘whites only’ spaces has still not changed. What has taken place is that blacks can now access those spaces of learning and living in order to immerse themselves in a western culture. Thus, for the blacks to enjoy the benefits of accessing those places they have to integrate into whiteness. Our integration is nothing but black people assimilating to what is still regarded as righteous, ordained, intelligent, beautiful and angelic whiteness.[14]

Richard Pithouse comments, with hope:

Liberalism has always been fundamentally tied up with the poisonous fantasy of its barbarian other. In 1859 John Stuart Mill, the great philosopher of English liberalism, declared, in his famous essay On Liberty, that “Despotism is a legitimate mode of dealing with barbarians”. The essential logic of actually existing liberalism – freedom for some, despotism for others – was never merely, as they say, academic. In 1887 Rhodes, speaking in parliament in Cape Town echoed these sentiments when he declared that: “we must adopt a system of despotism in our relations with the barbarians of South Africa”.

Yet in 2015, in a society still fundamentally shaped by the historical weight of this idea of freedom for some and despotism for others, a text book for first year politics students, written and prescribed in South African universities, a text book in which not a single African person is presented as a thinker worthy of study, declares that “Most discussions of freedom begin with John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty”.

This sort of academic consensus, which seemed entrenched a few weeks ago, no longer seems to have much of a future. The students have made an intervention of real weight and consequence.

In addressing the necessity of curricular transformation, Harry Garuba writes about the need for a “contrapuntal pedagogy that brings the knowledge of the marginalised to bear on our teaching… The Cecil John Rhodes statue at the centre of the upper campus of UCT may have been physically removed, but what we now need to move is the hegemonic gaze of the Rhodes that is lodged in our ways of thinking… our professional practices as teachers, academics, scholars and students. We need to take a critical look at our everyday routines… In short, we need to remove the Rhodes that lives in our disciplines and the curricula that underpin them.”[15]

—

Stories about the past do not only tell us where we come from. They also tell us where we belong and where we should be headed: they influence how we understand our present and imagine our future. Statues and memorials intentionally inscribe in space particular stories, effectively fixing in stone a version of the past chosen by those in power.

The spatial symbolic order at UCT is hard evidence of the university’s lack of transformation. The university, stretched across the lower slopes of Devil’s Peak, is a carefully curated memorial landscape that concretises colonial ideologies of power and knowledge: a site of prospect, and temple of rarefied knowledge on the hill. Moving through this space as individuals, we are forced to conduct a conversation with these imperial ideas: they exert their influence on us tangibly, directing our attention. Little has been changed about symbolism on the campus in the past twenty years, save for the additive naming of a few buildings and spaces after black icons: Steve Biko Student’s Union, Cissy Gool Plaza, Madiba Circle.

Dependent on one’s subject position, the power exerted by such spatial and ideological configurations feels more or less oppressive. As white people, we may not give much thought to whether we feel at home or belong in the landscape. Black people, on the contrary, constantly confronted by representations of white triumph at the expense of black lives, feel alienated and suffocated. SRC Chair Ramabina Mohapa said at the 16 March meeting convened by UCT management on Heritage Signage and Symbolism, before walking out with most of the student body present, that black students “can no longer breathe”.[16]

As already discussed, colonial dispositions are not easily apprehended or altered, because they remain hegemonic in wider society, rendering them invisible to those who fall on the privileged side of the colonial divide between those privileged and those not privileged.

However, moments in which the symbolic order is ruptured, like the toppling of the Rhodes statue, provide rare opportunities where the usually obscured hegemony becomes plainly apparent. It is at catalytic moments such as these that spacetime is malleable: contrapuntal conversations become possible, competing epistemologies thinkable; candid self-examination and interventions, too. Perhaps substantive transformation happens more effectively in sudden shifts than gradually.

I would like to close with a trio of comments that I gleaned from my Facebook feed on 10 April 2015, the day after Rhodes’ statue was removed.

We stop mistaking Rhodes for a good white person and we stop believing in white supremacy because everywhere you look you see white people’s statues – it’s almost as though there was no one here when they arrived and they just happened to discover the gold (which, coincidentally, was discovered by a black man). When the statues are gone, we can start asking the important questions like why are there 110 white male South African professors and not a single black female South African professor at UCT – South Africa’s most prestigious university. And questions like why is the curriculum at these universities so Eurocentric in its outlook with scant reflection on Africa and her rich history and her bright future. Without these statues and the prestige and honour bestowed on the founding fathers of white supremacy, the leaders of these institutions will have no choice but to answer those questions truthfully and reflect on those answers. Further, removing these reminders of the fallacy of white supremacy leaves space for black excellence to flourish without having to use the white gaze and its tools of measurement to validate itself.

– Fumbatha May

Watched Rhodes fall last night. I’ve never experienced such an atmosphere of happiness and liberation at UCT – particularly when the students refused to let the old bastard go gracefully but crowned him with a bucket of paint as he rode off into the sunset of empire. For the past few weeks, the students have been teaching the university its most important lesson in decades, and will continue to do so for a long time to come. At last, being at UCT is beginning to feel like being at a real university.

– Carlo Germeshuys

Driving home from work passed the plinth where Rhodes stood. It has a tag sprayed on the neat wood box that is covering the base: ‘C.J. WAS HERE ~>’ There is a black girl in a blue dress leaning up on it, smiling broadly as she chats to a white guy in green shorts who is sitting on the edge of it, swinging his legs as he rummages for something in his bookbag beside him. I swear there is a lighter feeling seeing that figure gone! An invitation to a new conversation.

– Debbie Pryor

These comments convey the general mood on campus well: there is a sense of hope and determination that the symbolic fall of Rhodes’ statue will be followed by deep institutional transformation, sentiments I share.

__

REFERENCES

Africa Network Expert Panel. 2014. Why are there so few black professors in South Africa? The Guardian Africa, 6 October 2014. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/oct/06/south-africa-race-black-professors

Althusser, L. 1971. “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes towards an Investigation)”. Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays. Verso.

Biko, S. 1988. I Write What I Like. London: Heinemann.

Friedman, S. 2015. “The racial denialism of South African liberals”. Rand Daily Mail. 1 April 2015. http://www.rdm.co.za/politics/2015/04/01/the-racial-denialism-of-south-african-liberals

Garuba, H. 2015. “What is an African curriculum?” Mail and Guardian, 17 April 2015 00:00. http://mg.co.za/article/2015-04-17-what-is-an-african-curriculum

Goodrich, A. 2015. “Statue controversies in South Africa – reimagine/recontextualise/replace” April 15, 2015. http://www.syntheticzero.net/2015/04/15/statue-controversies-in-south-africa-reimaginerecontextualisereplace/

Majavu, M. 2015. “Uct and Rhodes: Removing Statues, Dismantling Colonial Legacies”. Equal Times, 30 March 2015. http://www.equaltimes.org/uct-and-rhodes-removing-statues?lang=en#.VTUs9tyUd8E

Mangcu, X. 2015. Danger of ‘rationalist conceit’ in Cape Times, March 25 2015 at 01:52pm. http://www.iol.co.za/capetimes/danger-of-rationalist-conceit-1.1836933

Mangcu, X. 2015. “Assault on idea of academic freedom”. Cape Times,April 14 2015 at 01:44pm. http://www.iol.co.za/capetimes/assault-on-idea-of-academic-freedom-1.1844918.

Mignolo, W. 2002. “The Geopolitics of Knowledge and the Colonial Difference”. The South Atlantic Quarterly 101.1 (2002) 57-96. Duke University Press.

Mkhize, N. 2015. “Anger over Rhodes vindicates Mamdani”. Business Day, 7 April 2015. http://www.bdlive.co.za/opinion/columnists/2015/04/07/anger-over-rhodes-vindicates-mamdani

Moodie, A. 2010.”The Soudien Report: Deny racism at your peril”25 April 2010. University World News, Issue No:121. http://www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=20100424200305969

Mudimbe, V. 1988. The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy and the Order of Knowledge. London: James Curry.

Muller, S. 2014. “Transformation is not UCT’s priority”. Mail and Guardian 21 November 2014. http://mg.co.za/article/2014-11-21-transformation-is-not-ucts-priority

Nyamnjoh, F. 2012. “’Potted Plants in Greenhouses’: A Critical Reflection on the Resilience of Colonial Education in Africa”. Journal of Asian and African Studies. February 15, 2012. doi: 10.1177/0021909611417240.

O’Connell, S & Himmelman, N. 2011. “Lessons in continued oppression: UCT’s conception of post-apartheid freedom sets the bar too low”. https://concernedcasstudents.wordpress.com/2011/05/15/lessons-in-continued-oppression-ucts-conception-of-post-apartheid-freedom-sets-the-bar-too-low/

Pithouse, R. 2015. “South Africa in the Twilight of Liberalism”. Kafila, 19 April 2015. http://kafila.org/2015/04/19/south-africa-in-the-twilight-of-liberalism-richard-pithouse/

Soudien et al. 2008. Report of the Ministerial Committee on Transformation and Social Cohesion and the Elimination of Discrimination in Public Higher Education Institutions. 30 November 2008

Soudien, C. 2015 “UCT stands devoted to debate”. Cape Times, April 14 2015 at 12:43pm. http://www.iol.co.za/capetimes/uct-stands-devoted-to-debate-1.1844882

Wolpe, H. 1995. “The debate on university transformation in South Africa: The case of the University of the Western Cape.” Comparative Education, 31(2): 275 – 292.

___

[1] Attributed in “The lottery of life”, The Independent, 5 May 2001.

[2] From I Write What I Like: Selected Writings by Steve Biko, 1969 – 1972. Heinemann, 1987.

[3] Introduction to Black Skin, White Masks. Translated by Charles Lam Markmann. New York: Grove Press, 1967.

[4] Mignolo, 2002.

[5] Pithouse, 2015.

[6] See, for example, Soudien’s handling of a walkout by the SRC and Rhodes Must Fall during a meeting at UCT on “Heritage, Signage and Symbolism”, 16 March 2015: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4NgpJ00M5Ho

[7] Compare Soudien et al 2008; Alison Moodie’s 2010 interview with Soudien, entitled “The Soudien Report: Deny racism at your peril” and the defensive tone of Soudien 2015.

[8] Althusser, 1971. Interpellation is the process by which the ideology of an institution constitutes individual subjects’ identities through the process of the institution and its discourses ‘hailing’ them in social interactions.

[9] I would like to state as an aside that I do not believe it is the place of beneficiaries of structural racism to offer opinions on how transformation would be best effected. I believe white people should make space to listen and take cues from those who are still being squashed by the non-transformation of the society we inhabit as to what to do. Those who encounter the problem have far more authority in this matter. This is difficult for some white people to grasp due to an ingrained sense of entitlement, and the way whiteness and white knowledge regimes still have hegemonic authority. Several have accused me of promoting self-censorship. It is very far from that. As a white person, to make space for black voices at this moment in the way I am advocating is not to disengage from the debate. It is an active decision to be quiet, to listen and reflect, an action based on a recognition that unless we with white voices behave differently, the status quo of the balance of representation being skewed in the favour of white voices will not change materially.

[10] Friedman, 2015.

[11] Mkhize, 2015.

[12] The number of white professors at UCT stands at about 87 per cent, whereas black professors make up only 4 per cent of the professorial complement (Majavu, 2015).

[13] Nyamnjoh, 2012: 129-130.

[14] UCT SRC statement delivered by Ramabina Mahapa on 9 April 2015. http://www.uct.ac.za/dailynews/?id=9096

[15] Garuba, 2015.

[16] A video of the proceedings can be found at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4NgpJ00M5Ho.