Category Archives: poetry

aimless love – billy collins

This morning as I walked along the lakeshore,

I fell in love with a wren

and later in the day with a mouse

the cat had dropped under the dining room table.

In the shadows of an autumn evening,

I fell for a seamstress

still at her machine in the tailor’s window,

and later for a bowl of broth,

steam rising like smoke from a naval battle.

This is the best kind of love, I thought,

without recompense, without gifts,

or unkind words, without suspicion,

or silence on the telephone.

The love of the chestnut,

the jazz cap and one hand on the wheel.

No lust, no slam of the door –

the love of the miniature orange tree,

the clean white shirt, the hot evening shower,

the highway that cuts across Florida.

No waiting, no huffiness, or rancor –

just a twinge every now and then

for the wren who had built her nest

on a low branch overhanging the water

and for the dead mouse,

still dressed in its light brown suit.

But my heart is always propped up

in a field on its tripod,

ready for the next arrow.

After I carried the mouse by the tail

to a pile of leaves in the woods,

I found myself standing at the bathroom sink

gazing down affectionately at the soap,

so patient and soluble,

so at home in its pale green soap dish.

I could feel myself falling again

as I felt its turning in my wet hands

and caught the scent of lavender and stone.

__

(Thanks Debbie for this.)

From Aimless Love, Penguin Random House, 2014.

nostalghia (1983)

Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky’s film from 1983. I’m not going to link to any analysis here because to do so would narrow the interpretive possibilities of this opaque, allegorical masterpiece. Very superficially, though, the storyline is about a writer who, trapped by his fame and an unhappy marriage, seeks out his cultural past in Italy. Here he meets a local pariah who declares that the world is coming to an end. The writer finds this prophecy curiously more alluring than the possibility of a dead-end future. Nostalghia won the Grand Prix de Creation and the International Critics Prize at the 1984 Cannes Film Festival.

You can pick (slightly crappy) subtitles in several languages.

кумушки

“Among all the remarkable Usvyaty singers it is necessary, first and foremost, to single out the name of Olga Fedoseevna Sergeeva [I can’t find any English website for her]. We communicated with Olga Sergeeva for ten years and recorded over 300 songs in the most various genres performed by her. I brought the singer to Leningrad three times and she performed in ethnographic concerts in the House of Composers, on Leningrad radio and made some records with “Melodia” company.

“Sergeeva is an outstanding folk singer. Ritual songs and old lyric prevail in her richest repertoire which indicates the high artistic taste of Olga Sergeeva, as most of her contemporaries prefer singing new lyrical songs of the romance type. In the lyrical songs especially loved by the singer, her voice sounds plummy, deep–however, reserved at the same time and even subdued a bit, and from the very first sounds it spellbinds the listener with its beauty and cordiality.

“There is nothing outward, emotionally open in her performance, this is singing for herself with no relation to the listener. At the same time plainness, naturalness, strictness, is combined here with improvised freedom and excellence of micro variation. “Each song has one hundred changes”, the singer remarked once. It is not by chance that Andrei Tarkovsky chose the recording of Olga Sergeevas’s 1971/2 recording of the old song ‘Kumushki’ for his film Nostalghia.” (From HERE.)

The second version that follows here is also very beautiful, but a more contemporary interpretation, by singer Pelageya off her album Girls’ Songs in 2007.

Here is a translation of the words that I found:

Oh, my girlfriends, be sweet;

be sweet and love one another,

be sweet and love one another,

Love me too.

You will go to the green garden,

take me with you.

You will pick flowers,

Pick some for me too.

You will weave garlands,

take me with you.

You will go to the Donau,

take me with you.

You will offer your wreaths to the river,

offer mine too.

Your wreaths will float on the water,

but mine will sink to the bottom.

Your boyfriends came back from the war!

Mine didn’t return.

patti smith – kimberly (1975)

The wall is high, the black barn,

The babe in my arms in her swaddling clothes

And I know soon that the sky will split

And the planets will shift,

Balls of jade will drop and existence will stop.

Little sister, the sky is falling, I don’t mind, I don’t mind.

Little sister, the fates are calling on you.

Ah, here I stand again in this old ‘lectric whirlwind,

The sea rushes up my knees like flame

And I feel like just some misplaced Joan Of Arc

And the cause is you lookin’ up at me.

Oh baby, I remember when you were born,

It was dawn and the storm settled in my belly

And I rolled in the grass and I spit out the gas

And I lit a match and the void went flash

And the sky split and the planets hit,

Balls of jade dropped and existence stopped, stopped, stop, stop.

Little sister, the sky is falling, I don’t mind, I don’t mind.

Little sister, the fates are calling on you.

I was young ‘n crazy, so crazy I knew I could break through with you,

So with one hand I rocked you and with one heart I reached for you.

Ah, I knew your youth was for the takin’, fire on a mental plane,

So I ran through the fields as the bats with their baby vein faces

Burst from the barn and flames in a violent violet sky,

And I fell on my knees and pressed you against me.

Your soul was like a network of spittle,

Like glass balls movin’ in like cold streams of logic,

And I prayed as the lightning attacked

That something will make it go crack, something will make it go crack,

Something will make it go crack, something will make it go crack.

The palm trees fall into the sea,

It doesn’t matter much to me

As long as you’re safe, Kimberly.

And I can gaze deep

Into your starry eyes, baby, looking deep in your eyes, baby,

Looking deep in your eyes, baby, looking deep in your eyes, baby,

Into your starry eyes, oh.

Oh, in your starry eyes, baby,

Looking deep in your eyes, baby, looking deep in your eyes, baby, oh.

Oh, looking deep in your eyes, baby,

Into your starry eyes, baby, looking deep in your eyes, baby…

—

Simon Reynolds in a fascinating discussion with Patti Smith of her Horses album here.

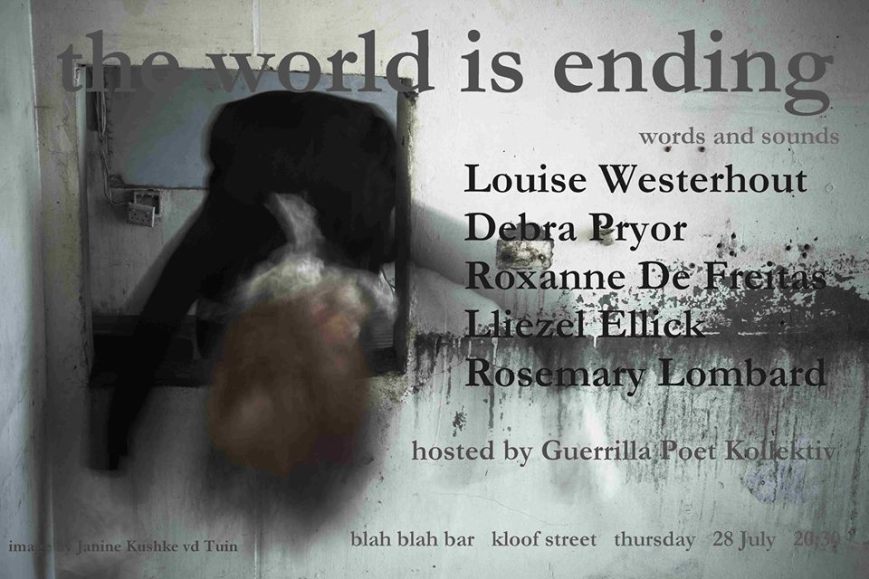

note to self (live at the blah blah bar)

A poem by Louise Westerhout, accompanied by Lliezel Ellick (cello) and Rosemary Lombard (autoharp), performed on 28 July 2016 at the Blah Blah Bar’s Open Mouth night.

Next time we’ll make sure we find a venue where rude men at the bar are not entitled to talk through performances…

gloomy sunday (live at the blah blah bar)

A version of the Rezsö Seress classic that we performed on 28 July 2016 as part of a collective which included Louise Westerhout, Lliezel Ellick, Rosemary Lombard, Debra Pryor and Roxanne de Freitas, at Blah Blah Bar’s “Open Mouth” night. We had had just two rehearsals, and I feel like this has the potential to go a lot further… Watch this space!

lotte lenya – lost in the stars

Lost in the Stars is a musical with score by Kurt Weill, based on the novel Cry, the Beloved Country (1948) by Alan Paton. The musical premiered on Broadway in 1949; it was the composer’s last work for the stage before he died the following year.

EDIT: The live performance I originally posted was removed from YouTube. Here is another version.

ruth white – spleen (1969)

From her 1969 album of interpretations of Baudelaire’s poetry, Flowers of Evil.

the world is ending

the smiths – cemetry gates (1986)

A dreaded sunny day

So I meet you at the cemetry gates

Keats and Yeats are on your side

A dreaded sunny day

So I meet you at the cemetry gates

Keats and Yeats are on your side

While Wilde is on mine

So we go inside and we gravely read the stones

All those people, all those lives

Where are they now?

With loves, and hates

And passions just like mine

They were born

And then they lived

And then they died

It seems so unfair

I want to cry

You say: “‘Ere thrice the sun done salutation to the dawn”

And you claim these words as your own

But I’ve read well, and I’ve heard them said

A hundred times (maybe less, maybe more)

If you must write prose/poems

The words you use should be your own

Don’t plagiarise or take “on loan”

‘Cause there’s always someone, somewhere

With a big nose, who knows

And who trips you up and laughs

When you fall

Who’ll trip you up and laugh

When you fall

You say: “‘Ere long done do does did”

Words which could only be your own

And then produce the text

From whence t’was ripped

(Some dizzy whore, 1804)

A dreaded sunny day

So let’s go where we’re happy

And I’ll meet you at the cemetry gates

Oh, Keats and Yeats are on your side

A dreaded sunny day

So let’s go where we’re wanted

And I’ll meet you at the cemetry gates

Keats and Yeats are on your side

But you lose

‘Cause weird lover Wilde is on mine

hera lindsay bird – keats is dead so fuck me from behind (2016)

Keats is dead so fuck me from behind

Keats is dead so fuck me from behind

Slowly and with carnal purpose

Some black midwinter afternoon

While all the children are walking home from school

Peel my stockings down with your teeth

Coleridge is dead and Auden too

Of laughing in an overcoat

Shelley died at sea and his heart wouldn’t burn

& Wordsworth……………………………………………..

They never found his body

His widow mad with grief, hammering nails into an empty meadow

Byron, Whitman, our dog crushed by the garage door

Finger me slowly

In the snowscape of your childhood

Our dead floating just below the surface of the earth

Bend me over like a substitute teacher

& pump me full of shivering arrows

O emotional vulnerability

Bosnian folk-song, birds in the chimney

Tell me what you love when you think I’m not listening

Wallace Stevens’s mother is calling him in for dinner

But he’s not coming, he’s dead too, he died sixty years ago

And nobody cared at his funeral

Life is real

And the days burn off like leopard print

Nobody, not even the dead can tell me what to do

Eat my pussy from behind

Bill Manhire’s not getting any younger

__

Read an interview with Hera Lindsay Bird at The Spinoff.

laure – (untitled)

pablo neruda – from sonnet xvii

“… I love you as certain dark things are to be loved,

in secret, between the shadow and the soul.

I love you as the plant that never blooms

but carries in itself the light of hidden flowers;

thanks to your love a certain solid fragrance,

risen from the earth, lives darkly in my body…”

__

From 100 Love Sonnets. Translated by Stephen Tapscott (UT Press, 1986).

mary oliver – not anyone who says

Not anyone who says, “I’m going to be

careful and smart in matters of love,”

who says, “I’m going to choose slowly,”

but only those lovers who didn’t choose at all

but were, as it were, chosen

by something invisible and powerful and uncontrollable

and beautiful and possibly even

unsuitable —

only those know what I’m talking about

in this talking about love.

___

From Felicity (Penguin Press, 2015).

yuki – “the snow” (edo period – late 1700s)

Yuki, “The Snow”, was composed by Koto Minezaki, and is considered one of the most difficult yet also iconic pieces of Jiuta, a traditional Japanese genre performed here by Shufu Abe. In many songs or theatrical pieces in which cold, dark weather is mentioned, the melody of Yuki’s instrumental interlude is employed as a leitmotif.

The character is reflecting on her string of failed love affairs. She decides to retreat from society and become a nun. As she walks towards the monastery, soft snow begins to fall.

INSTRUMENTS:

REIKIN (Steel-Stringed Koto/Lute)

SHAKUHACHI (Bamboo Flute)

HOTEKI (Japanese Flute)

Translation of the words (from HERE):

When I brush away

The flowers, and the snow-

How clear my sleeves become!

Truly it was an affair

Of long, long ago.

The man I waited for

May still be waiting for me.

The cry of the mandarin duck

Calling for his mate

From his freezing nest

Makes me feel sorrowful.

The temple bell at midnight

Wakes me

From my lonely reverie.

It makes me sad to hear

That distant temple bell.

When the patter of hail

Reaches my pillow,

I seem to hear, somehow,

His knocking on my door again.

And less and less am I able

To dam up my tears.

Freezing now

Into icicles.

I no longer care about

This hard, bitter life.

I’m only sorry that

I still can’t think of

My former lover as sinful.

Ah, the discarded sorrows!

The forsaken world of sorrow!

maya deren – ritual in transfigured time (1946)

Originally a silent film, this soundtrack was added by Nikos Kokolakis in 2015 – turn the sound off if you prefer.

About her fourth complete film, Ritual in Transfigured Time (1946), Maya Deren writes: “A ritual is an action that seeks the realisation of its purpose through the exercise of form… In this sense ritual is art; and even historically, all art derives from ritual. In ritual, the form is the meaning. More specifically, the quality of movement is not merely a decorative factor; it is the meaning itself of the movement. In this sense, this film is dance […] It’s an inversion towards life, the passage from sterile winter into fertile spring; mortality into immortality; the child-son into the man-father; or, as in this film, the widow into the bride”.

– Maya Deren: Chamber Films, program notes for a presentation, 1960

koleka putuma – water (2016)

michael rosen on fascism (2014)

I sometimes fear that

people think that fascism arrives in fancy dress

worn by grotesques and monsters

as played out in endless re-runs of the Nazis.

Fascism arrives as your friend.

It will restore your honour,

make you feel proud,

protect your house,

give you a job,

clean up the neighbourhood,

remind you of how great you once were,

clear out the venal and the corrupt,

remove anything you feel is unlike you…

It doesn’t walk in saying,

“Our programme means militias, mass imprisonments, transportations, war and persecution.”

From HERE.

adrienne rich – diving into the wreck

First having read the book of myths,

First having read the book of myths,

and loaded the camera,

and checked the edge of the knife-blade,

I put on

the body-armor of black rubber

the absurd flippers

the grave and awkward mask.

I am having to do this

not like Cousteau with his

assiduous team

aboard the sun-flooded schooner

but here alone.

There is a ladder.

The ladder is always there

hanging innocently

close to the side of the schooner.

We know what it is for,

we who have used it.

Otherwise

it is a piece of maritime floss

some sundry equipment.

I go down.

Rung after rung and still

the oxygen immerses me

the blue light

the clear atoms

of our human air.

I go down.

My flippers cripple me,

I crawl like an insect down the ladder

and there is no one

to tell me when the ocean

will begin.

First the air is blue and then

it is bluer and then green and then

black I am blacking out and yet

my mask is powerful

it pumps my blood with power

the sea is another story

the sea is not a question of power

I have to learn alone

to turn my body without force

in the deep element.

And now: it is easy to forget

what I came for

among so many who have always

lived here

swaying their crenellated fans

between the reefs

and besides

you breathe differently down here.

I came to explore the wreck.

The words are purposes.

The words are maps.

I came to see the damage that was done

and the treasures that prevail.

I stroke the beam of my lamp

slowly along the flank

of something more permanent

than fish or weed

the thing I came for:

the wreck and not the story of the wreck

the thing itself and not the myth

the drowned face always staring

toward the sun

the evidence of damage

worn by salt and sway into this threadbare beauty

the ribs of the disaster

curving their assertion

among the tentative haunters.

This is the place.

And I am here, the mermaid whose dark hair

streams black, the merman in his armored body.

We circle silently

about the wreck

we dive into the hold.

I am she: I am he

whose drowned face sleeps with open eyes

whose breasts still bear the stress

whose silver, copper, vermeil cargo lies

obscurely inside barrels

half-wedged and left to rot

we are the half-destroyed instruments

that once held to a course

the water-eaten log

the fouled compass

We are, I am, you are

by cowardice or courage

the one who find our way

back to this scene

carrying a knife, a camera

a book of myths

in which

our names do not appear.

__

From Diving into the Wreck: Poems 1971-1972. W. W. Norton & Company, 2013

maggie smith – good bones

alexis pauline gumbs – pulse (for the 50 and beyond)

A poem for those who died, shot in Pulse nightclub in Orlando this weekend past.

i was going to see you

i was going to dance

in the same place with you someday

i was going to pretend not to notice

how you and your friends smiled

when you saw me and my partner

trying to cumbia to bachata

but i was going to feel more free anyway

because you were smiling

and we were together

and you had your stomach out

and you felt beautiful in your sweat

i was going to smile when i walked by

i was going to hug you the first time

a friend of a friend introduced us

i was going to compliment your shoes

instead of writing you a love poem

i was going to smile every time i saw you

and struggle to remember your name

we were going to sing together

we were going to belt out Selena

i was going to mispronounce everything

except for amor

and ay ay ay

i was going to covet your confidence and your bracelet

i was going to be grateful for the sight of you

i was going scream YES!!! at nothing in particular

at everything especially

meaning you

meaning you beyond who i knew you to be

i was going to see you in hallways

and be too shy to say hello

you were going to come to the workshop

you were going to sign up for the workshop and not come

you were going to translate the webinar

even though my politics seemed out there

we were going to sign up for creating change the same day

and be reluctant about it for completely different reasons

we were going to watch the keynotes

and laugh at completely different times

i was going to hold your hand in a big activity

about the intimacy of strangers

about the strangeness of needing prayer

we were going to get the same automated voice message

when we complained that it was not what it should have been

we were going to be standing in the same line

for various overpriced drinks

during a shift change

i was going to breathe loudly so you would notice me

you were going to compliment my hair

it isn’t fair

because we were going to work

to beyonce and rihanna

and the rihanna’s and beyonce’s to come

and the beyonce’s and rihanna’s after that

we were going to not drink enough water

and stay out later than our immune systems could handle

we were going to sit in traffic in each others blindspots

listening to top 40 songs that trigger queer memories

just outside the scope of marketing predictions

we were going to get old and i was going to wonder

about the hint of a tattoo i could see under your sleeve

i was going to blink and just miss

the fought-for laughter lines around your liner-loved eyes

i was going to go out for my birthday

but i didn’t

and you did

we were going to be elders

just because we were still around

and i was going to listen to you on a panel

we didn’t feel qualified for

and hear you talk about your guilt

for still being alive

when so many of your friends were taken

by suicide

by AIDS

by racist police

and jealous ex-lovers

and poverty

and no access to healthcare

and how you had a stable job

you suffered at until the weekend

how you avoided the drama

and only went to the club at pride

and so here you were with no one to dance with anymore

i was going to see you and forget you

and only remember you in my hips

and how my smile came easier than clenching my teeth eventually

and how i finally learned whatever it is i still haven’t learned yet

i was going to hear you laugh and not know why

and not care

our ancestors fought for a future

and we were both going to be there

until we weren’t

and i don’t know if it would hurt more

to lose you later after knowing you

i don’t know if it would hurt more

to know you died on your own day

by your own hands

or any of the other systems

that stalk you and me and ours forever

i only know the pain that i am having

and that you are not here to share it

you are not here to bear it

you were going to pass me a candle at the next vigil

but now i am pulse

and now you

are flame.

mary oliver – praying

It doesn’t have to be

the blue iris, it could be

weeds in a vacant lot, or a few

small stones; just

pay attention, then patch

a few words together and don’t try

to make them elaborate, this isn’t

a contest but the doorway

into thanks, and a silence in which

another voice may speak.

From Thirst (Beacon Press, 2006).

on undoing the self and paying attention

Excerpted from this post at Wine, Women and Philosophy:

Excerpted from this post at Wine, Women and Philosophy:

… And aren’t unsettling folk just like that? You think you’ve done them, ticked them off, when suddenly, you’re back to square one… This other quagmire into which we had unwittingly waded – the actual technicalities involved in “undoing the creature in us” so as to successfully “decreate” a la Weil – required our immediate attention.

And so, spurred on by Anne Carson’s insight into how to go about actually paying attention – “Attention is a choice of where you put your mind…And looking at the object of your attention to the extent that you forget you’re doing the looking” – we embarked on a series of exercises designed to both instruct us on the ins and outs of destroying the “I,” and sharpen our skills in the attentiveness department.

Of course, there was a lot of preliminary discussion as to whether destroying the “I” was a desirable thing in the first place. In a sense, that Weilian notion of carving out a void in the space where the self normally resides goes counter to the rah-rah-be-your-biggest-and-best-self kind of rhetoric on offer in Self-Esteem for Dummies etc. In a culture where Self reigns Supreme, doing away with it is unnerving at best, terrifying at worst – even if this negation is, as Weil contends, a necessary move if one is to fully open oneself to Truth and Knowledge and Whatever Else Truly Matters.

For the self gets in the way. Like a shadow, it blocks out the light. Like unwanted baggage, it weighs you down. Like the elephant in the room, it takes up all the space. Clear the shadow, the baggage, the elephant, and you’re starting to get somewhere. A strange way to go about getting to the bottom of self-esteem, perhaps. But it seemed to offer something in the way of getting more out of life, and so we bit.

Simone Weil suffered from terrible migraines. She tried many ways of clearing them out of her head, but nothing seemed to work. One thing she knew for sure was that they got in the way of her being able to turn her full attention to what mattered. In April 1938 she found herself attending the Easter Mass at the Abbeye St-Pierre in Solesmes. She felt the Gregorian chanting of the monks enter her body, go straight to the space in her head filled with migraine. As the chanting poured in, her migraine did a peculiar thing: it emptied out. Soon, the space formerly known as migraine was awash with Gregorian Chant. It was a space rendered ready for paying attention: for “a patient holding in the mind,” as Weil referred to the act of paying attention, which in turn would make thought itself “available, empty, penetrable by the object.”

This is a radical take on the role of thought in the life of the mind: not the light bulb switching on as it encounters its object, but rather, the necessary conditions for the object to come to light. In Weil’s conception, thought must be suspended if the object of one’s attention is to find its way in, gain a proper foothold. If thought is busy thinking, the object just passes it by. If thoughtfulness hasn’t twinned itself up with attentiveness, the best we can hope for when it comes to thinking is a worrying – Weil would go so far as to say dangerous – mishmash of “partial attitudes.”

That, at least, is the theory. We obviously needed to put ourselves in Weil’s shoes to grasp what it felt like in practice. And so we experimented with filling our heads with the self-same Gregorian chants that had so impacted Weil, and making of the resulting void a luminous object-ready nesting ground. Yah, right. Weil, as I suggested earlier, was unsettling: not your average, run-of-the-mill, kind of gal.

But we gave it a go, and then turned our attention to other aural stimuli: a metronome’s steady tick-tocking, which brought the Weilian notion of time as “unvarying perpetuity” into the equation; a wind-up music box with its twirling ballerina and its ever-decelerating ditty, which prompted us to probe yet further how time, if invariably monotonous for Weil, could helpfully be categorized as either “time surpassed” – as in here comes the void, which is good monotonous – or as “time sterilized” – as in me just going round and round like “a squirrel turning it its cage” and never getting anywhere near the void, much less admitting to myself that I am going round and round (which for Weil is the worst sin of all, this kind of self-delusion) and which is, not surprisingly, bad monotonous.

This seemed as good a queue for a song as we were likely to get, so we broke out Anne Carson’s Duet of What is a Question from her Weil-inspired opera in three parts, Decreation (2005), and gave it our valiant best. Improvising the vocal arrangements – Carson had only supplied the libretto – provided us with the perfect opportunity to pay attention to each other, and hone our deep listening skills. As for getting us closer to the void, we were still a little in the dark. Enter American poet Fanny Howe (b.1940) and her beautifully observed prose poem, Doubt.

If Baruch Spinoza is the physicists’ philosopher, Simone Weil, it would seem, is the poets’ philosopher. Though it is easy to understand why Weil speaks to poets like Carson and Howe, the writing that comes of their interest in her ideas and her personal narrative is as tantalizing and challenging as Weil herself.

Sometimes, though, what poetry gives us that philosophy cannot is a line of such stark and heart-breaking beauty that knowing what the void, for example, actually is, or what it is to make one or find it or get there no longer seems to matter. For a very brief moment, we just feel decreated – like the creature in us has unraveled, like we have completely come undone.

fanny howe – doubt (2003)

Virginia Woolf committed suicide in 1941 when the German bombing campaign against England was at its peak and when she was reading Freud whom she had staved off until then.

Virginia Woolf committed suicide in 1941 when the German bombing campaign against England was at its peak and when she was reading Freud whom she had staved off until then.

Edith Stein, recently and controversially beatified by the Pope, who had successfully worked to transform an existential vocabulary into a theological one, was taken to Auschwitz in August 1942.

Two years later Simone Weil died in a hospital in England—of illness and depression—determined to know what it is to know.

She, as much as Woolf and Stein, sought salvation in a choice of words.

But multiples succumb to the sorrow induced by an inexact vocabulary.

While a whole change in discourse is a sign of conversion, the alteration of a single word only signals a kind of doubt about the value of the surrounding words.

Poets tend to hover over words in this troubled state of mind. What holds them poised in this position is the occasional eruption of happiness.

While we would all like to know if the individual person is a phenomenon either culturally or spiritually conceived and why everyone doesn’t kill everyone else, including themselves, since they can—poets act out the problem with their words.

Why not say “heart-sick” instead of “despairing”?

Why not say “despairing” instead of “depressed”?

Is there, perhaps, a quality in each person—hidden like a laugh inside a sob—that loves even more than it loves to live?

If there is, can it be expressed in the form of the lyric line?

Dostoevsky defended his later religious belief, saying of his work, “Even in Europe there have never been atheistic expressions of such power. My hosannah has gone through a great furnace of doubt.”

According to certain friends, Simone Weil would have given everything she wrote to be a poet. It was an ideal but she was wary of charm and the inauthentic. She saw herself as stuck in fact with a rational prose line for her surgery on modern thought. She might be the archetypal doubter but the language of the lyric was perhaps too uncertain.

As far as we know she wrote a play and some poems and one little prose poem called Prologue.

Yet Weil could be called a poet, if Wittgenstein could, despite her own estimation of her writing, because of the longing for a conversion that words might produce.

In Prologue the narrator is an uprooted seeker who still hopes that a transformation will come to her from the outside. The desired teacher arrives bearing the best of everything, including delicious wine and bread, affection, tolerance, solidarity (people come and go) and authority. This is a man who even has faith and loves truth.

She is happy. Then suddenly, without any cause, he tells her it’s over. She is out on the streets without direction, without memory. Indeed she is unable to remember even what he told her without his presence there to repeat it, this amnesia being the ultimate dereliction.

If memory fails, then the mind is air in a skull.

This loss of memory forces her to abandon hope for either rescue or certainty.

And now is the moment where doubt—as an active function—emerges and magnifies the world. It eliminates memory. And it turns eyesight so far outwards, the vision expands. A person feels as if she is the figure inside a mirror, looking outwards for her moves. She is a forgery.

When all the structures granted by common agreement fall away and that “reliable chain of cause and effect” that Hannah Arendt talks about—breaks—then a person’s inner logic also collapses. She moves and sees at the same time, which is terrifying.

Yet strangely it is in this moment that doubt shows itself to be the physical double to belief; it is the quality that nourishes willpower, and the one that is the invisible engine behind every step taken.

Doubt is what allows a single gesture to have a heart.

In this prose poem Weil’s narrator recovers her balance after a series of reactive revulsions to the surrounding culture by confessing to the most palpable human wish: that whoever he was, he loved her.

Hope seems to resist extermination as much as a roach does.

Hannah Arendt talks about the “abyss of nothingness that opens up before any deed that cannot be accounted for.” Consciousness of this abyss is the source of belief for most converts. Weil’s conviction that evil proves the existence of God is cut out of this consciousness.

Her Terrible Prayer—that she be reduced to a paralyzed nobody—desires an obedience to that moment where coming and going intersect before annihilation.

And her desire: “To be only an intermediary between the blank page and the poem” is a desire for a whole-heartedness that eliminates personality.

Virginia Woolf, a maestro of lyric resistance, was frightened by Freud’s claustrophobic determinism since she had no ground of defense against it. The hideous vocabulary of mental science crushed her dazzling star-thoughts into powder and brought her latent despair into the open air.

Born into a family devoted to skepticism and experiment, she had made a superhuman effort at creating a prose-world where doubt was a mesmerizing and glorious force.

Anyone who tries, as she did, out of a systematic training in secularism, to forge a rhetoric of belief is fighting against the odds. Disappointments are everywhere waiting to catch you, and an ironic realism is always convincing.

Simone Weil’s family was skeptical too, and secular and attentive to the development of the mind. Her older brother fed her early sense of inferiority with intellectual put-downs. Later, her notebooks chart a superhuman effort at conversion to a belief in affliction as a sign of God’s presence.

Her prose itself is tense with effort. After all, to convert by choice (that is, without a blast of revelation or a personal disaster) requires that you shift the names for things, and force a new language out of your mind onto the page.

You have to make yourself believe. Is this possible? Can you turn “void” into “God” by switching the words over and over again?

Any act of self-salvation is a problem because of death which always has the last laugh, and if there has been a dramatic and continual despair hanging over childhood, then it may even be impossible.

After all, can you call “doubt” “bewilderment” and suddenly be relieved?

Not if your mind has been fatally poisoned. . . .

But even then, it seems the dream of having no doubt continues, finding its way into love and work where choices matter exactly as much as they don’t matter—at least when luck is working in your favor.

—

Fanny Howe, from Gone: Poems. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

rainer maria rilke – les roses xvii

XVII

XVII

C’est toi qui prépares en toi

plus que toi, ton ultime essence.

Ce qui sort de toi, ce troublant émoi,

c’est ta danse.

Chaque pétale consent

et fait dans le vent

quelques pas odorants

invisibles.

Ô musique des yeux,

toute entourée d’eux,

tu deviens au milieu

intangible.

XVII

Your inner self is the one creating

more than yourself, your ultimate essence.

The uneasiness emerging from you,

that is your dance.

Each petal consents

and takes a few steps,

invisible, fragrant

in the wind.

O music to the eyes,

petals all around,

in their midst you become

intangible.

Rainer Maria Rilke (c 1926) From his series “Les Roses”, Jung Journal: Culture & Psyche,

5:4, 17-21. Translated from French by Susanne Petermann (2011).

rainer maria rilke – les roses xxi

XXI

XXI

Cela ne te donne-t-il pas le vertige

de tourner autour de toi sur ta tige

pour te terminer, rose ronde?

Mais quand ton propre élan t’inonde,

tu t’ignores dans ton bouton.

C’est un monde qui tourne en rond

pour que son calme centre ose

le rond repos de la ronde rose.

XXI

Doesn’t it make you dizzy, rose,

to spin on your stem around yourself

ending in your round self ?

Overwhelmed by your own momentum

you forget the bud that is you.

It’s a world that whirls around,

daring its calm center to hold

the round repose of the round rose.

Rainer Maria Rilke (c 1926) From his series “Les Roses”, Jung Journal: Culture & Psyche,

5:4, 17-21. Translated from French by Susanne Petermann (2011).

rilke on god

“Yet, no matter how deeply I go down into myself, my God is dark, and like a webbing made of a hundred roots that drink in silence. I know that my trunk rose from his warmth, but that’s all, because my branches hardly move at all near the ground, and just wave a little in the wind.”

“Yet, no matter how deeply I go down into myself, my God is dark, and like a webbing made of a hundred roots that drink in silence. I know that my trunk rose from his warmth, but that’s all, because my branches hardly move at all near the ground, and just wave a little in the wind.”

― Rainer Maria Rilke

paul celan – the no-one’s-rose (1963)

PSALM

No one kneads us again out of earth and clay,

no one incants our dust.

No one.

Blessed art thou, No One.

In thy sight would

we bloom.

In thy

spite.

A Nothing

we were, are now, and ever

shall be, blooming:

the Nothing-, the

No-One’s-Rose.

With

our pistil soul-bright,

our stamen heaven-waste,

our corona red

from the purpleword we sang

over, O over

the thorn.Paul Celan, “Psalm” from Selected Poems and Prose, translated by John Felstiner. Copyright © 2001 by John Felstiner.