Tag Archives: noise

writing wrongs

my wrists ache

wrest them

look out

a deck of shards

sick notes

cutting in

cutting up

cutting down

cutting out

cutting off

the pulse

wound up wound

wind up wind

wound up wind

wound down wind

wind down wound

wind up wounded

binds unbound

an unstruck sound

this name means nothing to me

rolling off my glossed tongue

the missing ink

the beads of spittle in the pink

the drown flying in my drink

sink for yourself

sink or blink

outside carries on

the whorl of a banshee

howling at the pane

open your eyes

close your mouth

close your eyes

open your mouth

open your close

eye your mouth

mouth your silence

silence your eyes

make the whirl go away

sudden infant – girl

The brand new video from the brand new album, Wölfli’s Nightmare (2014, Voodoo Rhythm Records). Produced by the über-distinguished Roli Mosimann, this is the first release from Sudden Infant as a trio:

Joke Lanz: vocals, electronics

Christian Weber: bass

Alexandre Babel: drums

this heat – deceit (full album)

Released on Rough Trade in 1981, Deceit is a dark, intense post-punk classic. Band member Charles Hayward said of the zeitgeist that shaped the album:

“The whole speak, ‘Little Boy’, ‘Big Boy’, calling missiles cute little names. The whole period was mad! We had a firm belief that we were going to die and the record was made on those terms.… The whole thing was designed to express this sort of fear, angst, which the group was all about, really… Some of the album was really plush sounding, some dim and pokey. Sometimes it would sound like the machinery was breaking up. We deliberately would make it sound as though the record player was exploding.”

Read more about this brilliant album at DROWNED IN SOUND.

Track List

Sleep 0:00

Paper Hats 2:14

Triumph 8:17

S.P.Q.R. 11:12

Cenotaph 14:41

Shrink Wrap 19:20

Radio Prague 21:01

Makeshift Swahili 23:23

Independence 27:27

A New Kind Of Water 31:09

Hi Baku Shyo 36:06

__________________________________

Charles Hayward — Vocals, Bass Guitar, Keyboards, Drums, Tape Music

Gareth Williams — Vocals, Bass Guitar, Keyboards, Tape Music

Charles Bullen — Vocals, Clarinet, Guitar, Drums, Tape Music

David Cunningham — Production

Martin Frederick — Mixing

Laurie-Rae Chamberlain — Colour Xerography

Nicholas Goodall — Sleeve Photography Direction

Studio 54 — Sleeve Design

roald dahl – the sound machine (1949)

For a while longer, Klausner fussed about with the wires in the black box; then he straightened up and in a soft excited whisper said, “Now we’ll try again… We’ll take it out into the garden this time… and then perhaps, perhaps… the reception will be better. Lift it up now… carefully… Oh, my God, it’s heavy!”

He carried the box to the door, found that he couldn’t open the door without putting it down, carried it back, put it on the bench, opened the door, and then carried it with some difficulty into the garden. He placed the box carefully on a small wooden table that stood on the lawn. He returned to the shed and fetched a pair of earphones. He plugged the wire connections from the earphones into the machine and put the earphones over his ears. The movements of his hands were quick and precise. He was excited, and breathed loudly and quickly through his mouth. He kept on talking to himself with little words of comfort and encouragement, as though he were afraid–afraid that the machine might not work and afraid also of what might happen if it did. He stood there in the garden beside the wooden table, so pale, small and thin that he looked like an ancient, consumptive, bespectacled child.

The sun had gone down. There was no wind, no sound at all. From where he stood, he could see over a low fence into the next garden, and there was a woman walking down the garden with a flower-basket on her arm. He watched her for a while without thinking about her at all. Then he turned to the box on the table and pressed a switch on its front. He put his left hand on the volume control and his right hand on the knob that moved a needle across a large central dial, like the wavelength dial of a radio. The dial was marked with many numbers, in a series of bands, starting at 15,000 and going on up to 1,000,000. And now he was bending forward over the machine. His head was cocked to one side in a tense, listening attitude. His right hand was beginning to turn the knob.

The needle was travelling slowly across the dial, so slowly he could hardly see it move, and in the earphones he could hear a faint, spasmodic crackling. Behind this crackling sound he could hear a distant humming tone which was the noise of the machine itself, but that was all. As he listened, he became conscious of a curious sensation, a feeling that his ears were stretching out away from his head, that each ear was connected to his head by a thin stiff wire, like a tentacle, and that the wires were lengthening, that the ears were going up and up towards a secret and forbidden territory, a dangerous ultrasonic region where ears had never been before and had no right to be. The little needle crept slowly across the dial, and suddenly he heard a shriek, a frightful piercing shriek, and he jumped and dropped his hands, catching hold of the edge of the table.

He stared around him as if expecting to see the person who had shrieked. There was no one in sight except the woman in the garden next door, and it was certainly not she. She was bending down, cutting yellow roses and putting them in her basket. Again it came–a throatless, inhuman shriek, sharp and short, very clear and cold. The note itself possessed a minor, metallic quality that he had never heard before.

Klausner looked around him, searching instinctively for the source of the noise. The woman next door was the only living thing in sight. He saw her reach down; take a rose stem in the fingers of one hand and snip the stem with a pair of scissors. Again he heard the scream. It came at the exact moment when the rose stem was cut. At this point, the woman straightened up, put the scissors in the basket with the roses and turned to walk away.

“Mrs Saunders!” Klausner shouted, his voice shrill with excitement. “Oh, Mrs Saunders!” And looking round, the woman saw her neighbour standing on his lawn–a fantastic, arm-waving little person with a pair of earphones on his head–calling to her in a voice so high and loud that she became alarmed. “Cut another one! Please cut another one quickly!”

She stood still, staring at him. “Why, Mr Klausner,” she said, “What’s the matter?”

“Please do as I ask,” he said. “Cut just one more rose!”

Mrs Saunders had always believed her neighbour to be a rather peculiar person; now it seemed that he had gone completely crazy. She wondered whether she should run into the house and fetch her husband. No, she thought. No, he’s harmless. I’ll just humour him.

“Certainly, Mr Klausner, if you like,” she said.

She took her scissors from the basket, bent down and snipped another rose. Again Klausner heard that frightful, throatless shriek in the earphones; again it came at the exact moment the rose stem was cut. He took off the earphones and ran to the fence that separated the two gardens. “All right,” he said. “That’s enough. No more. Please, no more.”

The woman stood there, a yellow rose in one hand, clippers in the other, looking at him.”I’m going to tell you something, Mrs Saunders,” he said, “something that you won’t believe.” He put his hands on top of the fence and peered at her intently through his thick spectacles. “You have, this evening, cut a basketful of roses. You have, with a sharp pair of scissors, cut through the stems of living things, and each rose that you cut screamed in the most terrible way. Did you know that, Mrs Saunders?”

“No,” she said. “I certainly didn’t know that.”

“It happens to be true,” he said. He was breathing rather rapidly, but he was trying to control his excitement. “I heard them shrieking. Each time you cut one, I heard the cry of pain. A very high-pitched sound, approximately one hundred and thirty-two thousand vibrations a second. You couldn’t possibly have heard it yourself. But I heard it.”

“Did you really, Mr Klausner?” She decided she would make a dash for the house in about five seconds.

“You might say,” he went on, “that a rose bush has no nervous system to feel with, no throat to cry with. You’d be right. It hasn’t. Not like ours, anyway. But how do you know, Mrs Saunders”–and here he leaned far over the fence and spoke in a fierce whisper, “how do you know that a rose bush doesn’t feel as much pain when someone cuts its stem in two as you would feel if someone cut your wrist off with a garden shears? How do you know that? It’s alive, isn’t it?”

“Yes, Mr Klausner. Oh, yes and good night.”

Quickly she turned and ran up the garden to her house. Klausner went back to the table. He put on the earphones and stood for a while listening. He could still hear the faint crackling sound and the humming noise of the machine, but nothing more. He bent down and took hold of a small white daisy growing on the lawn. He took it between thumb and forefinger and slowly pulled it upward and sideways until the stem broke. From the moment that he started pulling to the moment when the stem broke, he heard–he distinctly heard in the earphones–a faint high-pitched cry, curiously inanimate.

He took another daisy and did it again. Once more he heard the cry, but he wasn’t sure now that it expressed pain. No, it wasn’t pain; it was surprise. Or was it? It didn’t really express any of the feelings or emotions known to a human being. It was just a cry, a neutral, stony cry–a single, emotionless note, expressing nothing. It had been the same with the roses. He had been wrong in calling it a cry of pain. A flower probably didn’t feel pain. It felt something else which we didn’t know about–something called tom or spun or plinuckment, or anything you like.

He stood up and removed the earphones. It was getting dark and he could see pricks of light shining in the windows of the houses all around him. Carefully he picked up the black box from the table, carried it into the shed and put it on the workbench. Then he went out, locked the door behind him and walked up to the house.

The next morning Klausner was up as soon as it was light. He dressed and went straight to the shed. He picked up the machine and carried it outside,clasping it to his chest with both hands, walking unsteadily under its weight. He went past the house, out through the front gate, and across the road to the park.There he paused and looked around him; then he went on until he came to a large tree, a beech tree, and he placed the machine on the ground close to the trunk of the tree.

Quickly he went back to the house and got an axe from the coal cellar and carried it across the road into the park. He put the axe on the ground beside the tree. Then he looked around him again, peering nervously through his thick glasses in every direction. There was no one about. It was six in the morning.He put the earphones on his head and switched on the machine. He listened for a moment to the faint familiar humming sound; then he picked up the axe, took a stance with his legs wide apart and swung the axe as hard as he could at the base of the tree trunk.

The blade cut deep into the wood and stuck there, and at the instant of impact he heard a most extraordinary noise in the earphones. It was a new noise, unlike any he had heard before–a harsh, noteless, enormous noise, a growling, low pitched, screaming sound, not quick and short like the noise of the roses, but drawn out like a sob lasting for fully a minute, loudest at the moment when the axe struck, fading gradually fainter and fainter until it was gone.

—

Excerpted from Roald Dahl’s short story, “The Sound Machine”, first published in The New Yorker on September 17, 1949. Read the full story HERE.

sonic youth – daydream nation (full album)

1988. Enigma Records. Essential.

00:00 Teen Age Riot

06:58 Silver Rocket

10:46 The Sprawl

18:29 ‘Cross the Breeze

25:29 Eric’s Trip

29:18 Total Trash

36:52 Hey Joni

41:14 Providence

43:56 Candle

48:55 Rain King

53:35 Kissability

56:44 Trilogy: a)The Wonder b)Hyperstation c)Eliminator Jr.

ride – drive blind

“Windows all open, chaos in my hair…” from Smile (Creation Records, 1990).

marie laforêt – la voix du silence

A cover of Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Sound of Silence” on Laforêt’s Album 3 (Disques Festival, 1967). The video contains footage from the film, The Graduate (1967), in which this and other Simon and Garfunkel songs feature prominently during pivotal montage scenes.

signal to noise

kim gordon & ikue mori – la casa encendida

Live performance, 28 July 2012, Madrid.

sylvain chauveau – je suis vivant et vous etes morts

From The Black Book Of Capitalism (2008)

zeena parkins & ikue mori – phantom orchard

where the echoes stop

Erwin Raphael McManus – Where the Echoes Stop

I want to stand where the echoes stop.

Far past where sound has abandoned thought.

Where silence reigns over redundancy.

Where once well said is more than enough.I want to stand where the echoes stop.

Where words must be born to be heard.

Where speech is a gift and not a curse.

Where there is more of the unique and less of the mundane.I want to stand where the echoes stop.

Where meaning is rescued from noise…

Where conviction replaces thoughtless repetition…

Where what everyone is saying surrenders to what needs to be said.I want to stand where the echoes stop.

Where the shouting of the masses falls silent to the whisper of the one…

Where the voice of the majority submits to the voice of reason…

Where “they” do not exist; but “we” do.I want to stand where the echoes stop.

Where substance overthrows the superficial…

Where courage conquers compliance and conformity…

Where words do not travel farther than the person who speaks them.I want to stand where the echoes stop.

Where I only say what I believe.

Where I only repeat what changes me.

Where empty words finally rest in peace.“Be still and know that I am God…” — Psalm 46:10a

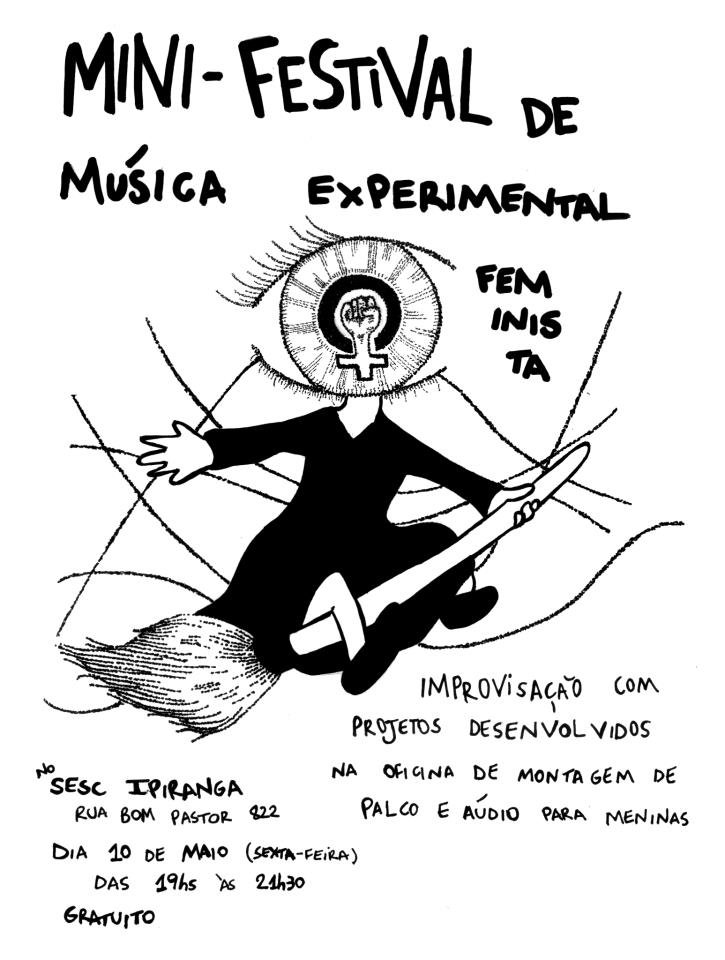

primeiro mini-festival de música experimental feminista

Happening this weekend in Sao Paulo:

More info on Facebook, HERE.

whatever floats your boat

nina hagen – born in xixax (1982)

This is again radio Yerevan with… our news (claps)

Oh, I’m sorry, you should turn on the machine

This is radio Yerevan, (laughs)

my name is Hans Ivanovich (laughs) Hagen and this is…

The news (laughs)

Continue reading

julia holter – goddess eyes 1

“The first thing that came to mind was an image that gradually deteriorates with visual noise, echoing the sonic noise present in the song. We go from lightness to darkness, away from a structured, fabricated place and into raw territory.”

~ Jose Wolff – August, 2012

Music by Julia Holter

Directed by Jose Wolff

Photography by Robson Muzel and Jose Wolff

“Broken figure” portrayed by Bryan Dodds

Shot on site at The Wulf, Elysian Park, and the Angeles Angeles Natural Forest. Special thanks to Emily Jane Kuntz and Eric KM Clark and Michael Winter at The Wulf

©2012 RVNG Intl.

thundersqueak on the edge of wrong (2009)

Thundersqueak — the noise trio of Gareth Dawson, Righard Kapp and Mark van Niekerk — performing live at Cape Town’s 4th annual festival of improvised music, ‘On The Edge of Wrong’ 2009. Filmed by Jaco Minnaar.

Righard and Gareth will be playing together tonight at this year’s EDGE OF WRONG.

but, soft!

no pillow

could swallow

my scream

if it started

noise and capitalism

“This book, Noise and Capitalism, is a tool for understanding the situation we are living through, the way our practices and our subjectivities are determined by capitalism. It explores contemporary alienation in order to discover whether the practices of improvisation and noise contain or can produce emancipatory moments and how these practices point towards social relations which can extend these moments.

If the conditions in which we produce our music affects our playing then let’s try to feel through them, understand them as much as possible and, then, change these conditions.

If our senses are appropriated by capitalism and put to work in an ‘attention economy’, let’s, then, reappropriate our senses, our capacity to feel, our receptive powers; let’s start the war at the membrane! Alienated language is noise, but noise contains possibilities that may, who knows, be more affective than discursive, more enigmatic than dogmatic.

Noise and improvisation are practices of risk, a ‘going fragile’. Yet these risks imply a social responsibility that could take us beyond ‘phoney freedom’ and into unities of differing.

We find ourselves poised between vicariously florid academic criticism, overspecialised niche markets and basements full of anti-intellectual escapists. There is, after all, ‘a Franco, Churchill, Roosevelt, inside all of us…’ yet this book is written neither by chiefs nor generals.

Here non-appointed practitioners, who are not yet disinterested, autotheorise ways of thinking through the contemporary conditions for making difficult music and opening up to the wilfully perverse satisfactions of the auricular drives.”

Sound interesting? HERE, DOWNLOAD NOISE AND CAPITALISM FREE.

Edited by Mattin Iles and Anthony Iles

Contributions from Ray Brassier, Emma Hedditch, Matthew Hyland, Anthony Iles, Sara Kaaman, Mattin, Nina Power, Edwin Prévost, Bruce Russell, Matthieu Saladin, Howard Slater, Csaba Toth, Ben Watson.

More details from the publishers, Arteleku Audiolab (Kritika series), Donostia-San Sebastián (Gipuzkoa)

Publication date: September 2009

t,o,u,c,h,i,n,g

TOUCHING is a 1969 short film by Paul Sharits.

“There are moments in cinematic art when the narrative of the film is subjectively implied and subsequently written by the viewer. While this is common to most structural and lyrical films in the experimental genre, none hits louder than T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G, an angry and demonic piece that simultaneously lulls you into awareness and hypnotizes you into an emotive overload.”

nurse with wound – i’ve plummed this whole neighbourhood

This video is from the VHS compilation 23 Eazy Pieces (copyright 1990 by Home Video Club.) The song is from the compilation album Drastic Perversions and the video is by John Zewizz.

niklas zimmer – thinking aloud through the archives that sound

Along with Niklas, I attended a fascinating workshop at UCT last month – these are his reflections:

From August 22 to 24 this year, the Archive and Public Culture research initiative hosted a workshop, led by research fellow Dr Anette Hoffmann, under the title ‘sound/archive/voice/object.’ True to the trans-disciplinary spirit of APC, the range of academic positions present was heterogeneous, but beyond that, this workshop attracted a significant set of participants from beyond the institution: over three days in the much-loved Jon Berndt thought space, the voices of radio activism, sound art, turntablism and composition for film and theatre cross-faded with those of ethnomusicology, social anthropology, fine art and historical studies.

Dr Hoffmann’s carefully staged set of daily readings, gentle chairing and inspiring listening experiences of samples of ethnographic phonograph-recordings from Berlin’s Lautarchiv enabled us to begin thinking through the subject of sound in all its complexity. While ‘visual culture’ with its associated tropes has become commonplace, the same cannot be said for ‘sonic’ or ‘aural culture’ – the need for understanding sound (historically, psychologically, physiologically, etc.) is immanent, particularly when dealing with records of human subject research in the archive.

‘… sound is a product of the human senses and not a thing in the world apart from humans. Sound is a little piece of the vibrating world.’ (Jonathan Sterne)

As with other investigations into reproduction technologies developed in the 19th century (such as photography), a detailed understanding of the political, scientific and cultural drives that gave birth to them in the first place is key to surfacing relevant, contemporary perspectives on the audio archive. Studies into sound – and in particular the ethnographic voice recording – have so far remained in relative specialist isolation. In contrast to this, studies of visuality – and in particular ethnographic photographic portraiture – have been gaining interdisciplinary popularity. Beyond the misalignments of comparison between the two, and despite the multitude of overlaps between the orders of the eye and the ear, it becomes clear that the realms of the aural (or sonic) and the visual do require different sets of analytical tools.

‘The vocabulary may well distinguish nuances of meaning, but words fail us when we are faced with the intimate shades of the voice, which infinitely exceed meaning. (…) faced with the voice, words structurally fail.’ (Mladen Dolar)

Passive hearing and active listening involve a complex range of affective and cognitive processes which are incomparable to those associated with any other sense (other than perhaps touch) – any discussion of differences in technology for the capture and representation of aural as opposed to visual phenomena can only be secondary to this. In the shared process of active listening at the beginning of each workshop morning, the group sensed its way into some of the qualities of sound, particularly those of the speaking voice. We discovered that we are able to hear much more than we tend to trust ourselves to. The ethnographic and linguistic phonographic recordings of prisoners of war in WWI Germany from the Humboldt University’s Lautarchiv in Berlin revealed to us as listeners a small, but powerful glimpse into the potential of a different way of working with archival material. Because the transcripts and translations of the recordings were withheld until after the first listening-through, we relied on our own emotional and intellectual inferences in order to engage the questions that these ‘sound objects’ from the past carried into our present space. Listening engages us in a different way of knowing, as Dr Hoffmann pointed out, and ‘if the process of enunciation points at the locus of subjectivity in language, then voice also sustains an intimate link with the very notion of the subject.’ (Mladen Dolar)

Generally, the bigger paradigm of any research interest will at first tend towards sacrificing the individual voice to generalisation and dissection rather than a ‘regime of care’ as Prof Hamilton would remind us: sounds, in particular human voices on record are always re-presented in a web of power-relations, some of which are near-impossible to address, let alone shift. This becomes most paradoxical in thinking though the subaltern speaking position in the archive, where not only the act of recording has been an act of violence, but where the act of listening itself can be an act of othering and continued silencing. In view of this (in sound of this?), the best possible approach to reaching the necessary ‘audio condition’ from which to push at the limits of subaltern positionalities in the archive seems to be continuum of analysis, a reverence paid to the minutiae of humanity in the material. This was a recurring moment, a leitmotiv in our three days of sound studies: only a wide range of disciplines working together can actually achieve the description of the necessary aspects (aesthetic, ethical, cultural, historical, political, psychological) from which to consider a relevant engagement with the archive that sounds.

![[Artist unknown]](https://fleurmach.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/afloat-in-the-static.jpg?w=869)