Category Archives: embodiment

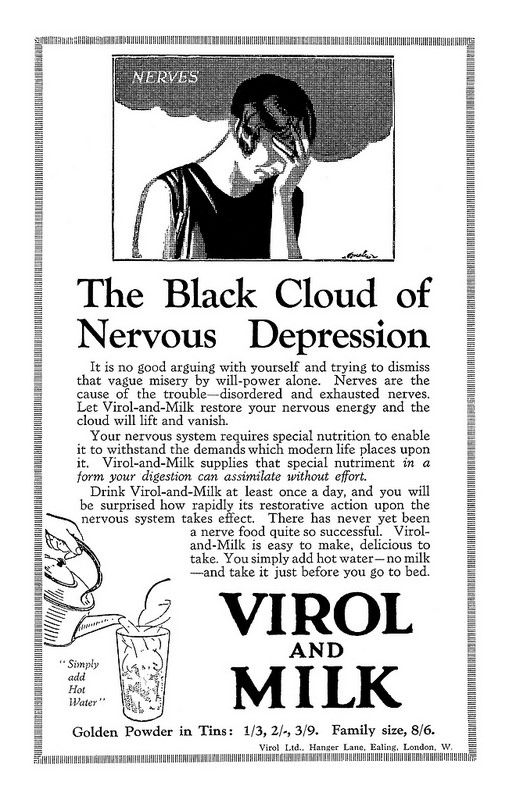

advertisement for virol and milk, 1927

gaelynn lea – npr music tiny desk concert (2016)

“Bird, why do you sing?

Fate has clipped your wings.”

Read Gaelynn on keeping inner demons at bay.

Thank you Derek Davey for introducing me to this artist.

“the quickening art”(2008)

“The past which is not recoverable in any other way is embedded, as if in amber, in the music, and people can regain a sense of identity…”— Oliver Sacks

So utterly incredible.

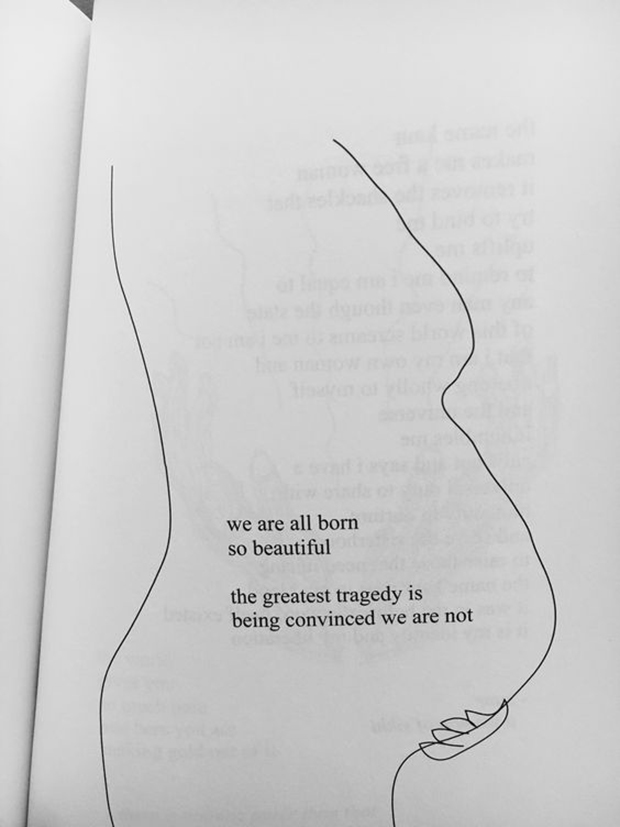

rupi kaur – we are all born beautiful (2014)

From milk and honey.

sleep tight, capucine (2006-2016)

john perkins on empire’s power tools

urgent call for help by art students under threat from paramilitary security on campus

#umhlangano

Dear Comrades, Allies and Supporters.

WE NEED YOUR URGENT HELP. TOMORROW IS D-DAY FOR #UMHLANGANO

WE ALSO NEED VISIBLE SUPPORT OUTSIDE AND INSIDE OUR CAMPUS TOMORROW. GATHER AT 5 AM, CAMPUS FORMERLY KNOWN AS HIDDINGH, ORANGE STREET, GARDENS. COME DRESSED PLAYFULLY. WE WANT A PLAYFUL, CREATIVE PERFORMANCE, THE MORE RIDICULOUS THE BETTER. WE DO NOT NEED TO BE BRUTALISED FOR THIS OKAY?

On Monday #october3 Max Price, the Vice Chancellor of the University of Cape Town says the he will send private security to #openUCT. Government has given the go-ahead to use force to reopen school.

We, #Umhlangano, are in direct talks with the Dean of Humanities and the staff of Drama and Fine Art.

We are intervening peacefully, making art, performance and play making on the Campus Formerly Known as Hiddingh. We are exploring non-violent responses to police brutality and private security occupation on our campuses. On Monday, the institution sends former soldiers, dressed in private security uniforms, in full body armour against us. For making art, for intervening peacefully, for doing the work that they just want us to study, but we guess, not actually practice.

Artists are expected to intervene in society. To make meaningful contribution, to shift the status quo. Nothing about this is right. Nothing about this is fair. Nothing about this is either democratic or reasonable.

We are trying to make safe space to explore what a free decolonial education looks like after years of listening to how the institution just needs time to implement substantive reforms but never does.

If Max Price and the UCT council get their way, on Monday none of us are safe on campus. We will be teargassed, brutalised and shot at. Even the sight of these weaponised security guards has triggered PTSD symptoms in most of us. We watched members of our collective crumbling before us. Those who had , the previous week, drew courage from the power of love and creativity now trembled and sobbed in the arms of their cadres. The action we took came from a belly-deep desperation to be heard, to be visible and regarded as equals.

If you visit the website of the privatised private security company that they will send against us. http://www.vetusschola.co.za to understand why we are so concerned. Why we have slept with one eye on the door and know why #october3 we will be finding creative ways to keep ourselves, and other vulnerable student safer, no matter what violence sent against us. We need your help, write letters, write emails, make facebook posts, tweet @uct_news and blow up Max Price’s email (vc@uct.ac.za) Please, no more violence. Please, no more teargas, stun grenades, no more bleeding brutalised students. USE WHATEVER CHANNEL YOU CAN.

More love, more music, more art, more play, more collaboration.

#UMHLANGANO

#BLACKLIVESMATTER

PLEASE SHARE, WE NEED THIS VIRAL BEFORE TOMORROW MORNING.

cecilia ferreira – belle (2013)

Making up is hard to do.

shilpa ray – nocturnal emissions (2012)

Off Last Year’s Savage. I love this video, which, according to Shilpa Ray, is a commentary on the conservative reproductive rights lobby, inspired by the Todd Akin controversy.

Here comes that ticker tape parade

Bless all my lucky stars

Cause I’ve saved the day

There goes my ego exploding

In mushroom clouds all over

My third world body

Well this air’s better

And I’m wetter

And taste just like ice cream

Don’t ever wake me up, bitch

Don’t ever wake me up

From where the gifts are pouring

The fans adoring

All the trophies that I win

I am the King

I am the King

Pretty soon I’m gonna have to let it go

Pretty soon I’m gonna have to let it go

In my fifteen hours of sleep

There’s no more suffering me

Maybe some suffering for you

This is my regime

And it’s perpetual pageantry

There’s no existence of my mistakes

No humility

Well my dick’s bigger

My breasts are thicker

Whatever power means

Don’t ever wake me up, bitch

Don’t ever wake me up

From where I’m well fed

I’m well bred

Shitting 24ct bricks

I am the King

I am the King

And pretty soon I’m gonna have to let it go

And pretty soon I’m gonna have to let it go

Pretty soon I’m gonna have to let it go

In my 15 hours of sleep

Here comes that ticker tape parade

And there goes my ego exploding

Here comes that ticker tape parade

There goes my ego exploding

Here comes that ticker tape parade

There goes my ego exploding

a message to all you guys and gals (2016)

The makeup tutorial to end all makeup tutorials.

donna haraway – anthropocene, capitalocene, cthulucene: staying with the trouble (5 september 2014)

Sympoiesis, not autopoiesis, threads the string figure game played by Terran critters. Always many-stranded, SF is spun from science fact, speculative fabulation, science fiction, and, in French, soin de ficelles (care of/for the threads). The sciences of the mid-20th-century “new evolutionary synthesis” shaped approaches to human-induced mass extinctions and reworldings later named the Anthropocene. Rooted in units and relations, especially competitive relations, these sciences have a hard time with three key biological domains: embryology and development, symbiosis and collaborative entanglements, and the vast worlds of microbes. Approaches tuned to “multi-species becoming with” better sustain us in staying with the trouble on Terra. An emerging “new new synthesis” in trans-disciplinary biologies and arts proposes string figures tying together human and nonhuman ecologies, evolution, development, history, technology, and more. Corals, microbes, robotic and fleshly geese, artists, and scientists are the dramatis personae in this talk’s SF game.

For Donna Haraway, we are already assimilated.

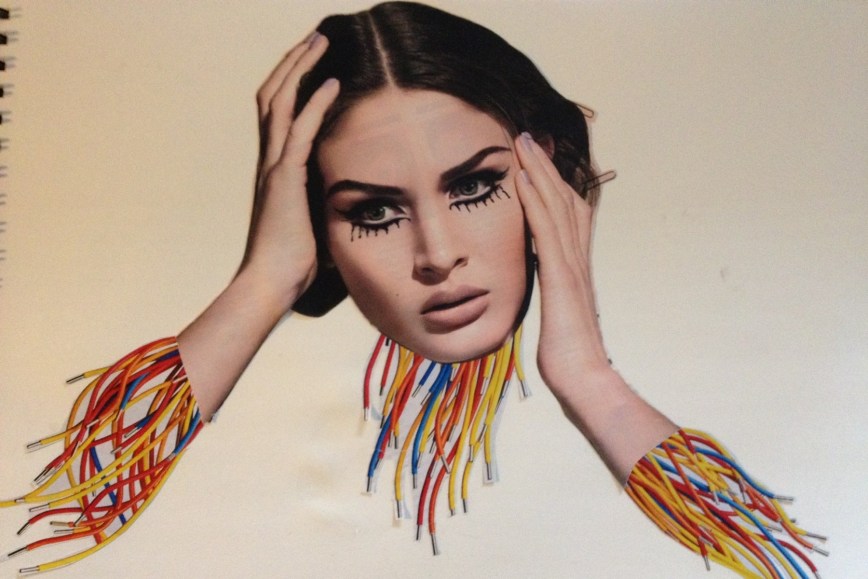

“The monster opens the curtains of Victor Frankenstein’s bed. Schwarzenegger tears back the skin of his forearm to display a gleaming skeleton of chrome and steel. Tetsuo’s skin bubbles as wire and cable burst to the surface. These science fiction fevered dreams stem from our deepest concerns about science, technology, and society. With advances in medicine, robotics, and AI, they’re moving inexorably closer to reality. When technology works on the body, our horror always mingles with intense fascination. But exactly how does technology do this work? And how far has it penetrated the membrane of our skin?”

Go HERE to read the rest of this article about Donna Haraway from way back in 1997.

bomba estéreo – soy yo (2016)

“Lo único que importa es lo que esta por dentro,” – you’re the only one whose opinions on you matter.

Written by Liliana Margarita Saumet Avila, Eric Frederic, Joe Spargur, Federico Simon Mejia Ochoa, this catchy anthem is from their 2015 album Amanecer .

Mejía: On this one, we recorded a couple of traditional Colombian instruments live – which is something we like to do on all of our albums. It has a gaita [a folkloric wind instrument of indigenous origin] and a tambor alegre [a percussion instrument of African origin used in cumbia music]. It’s a really fun song and the most Colombian one on the album.

Saumet: The lyrics are about respecting people for who they are and not trying to change them. Sometimes as people we tend to judge others too much. So what if people criticize you? That’s the way you are.

river

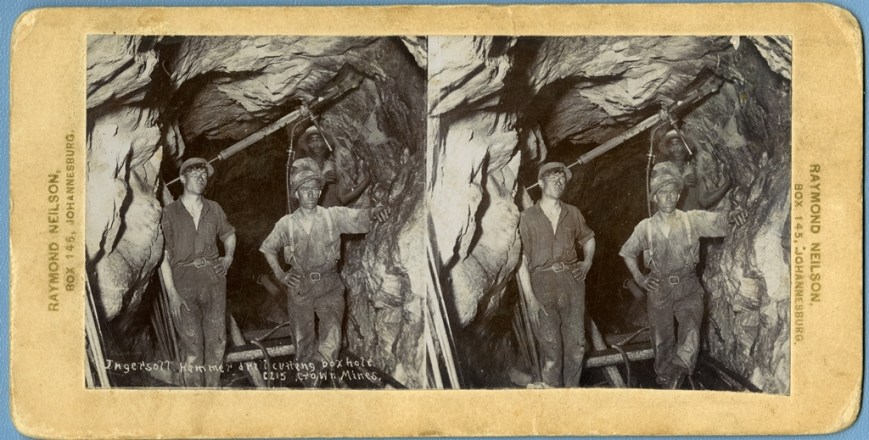

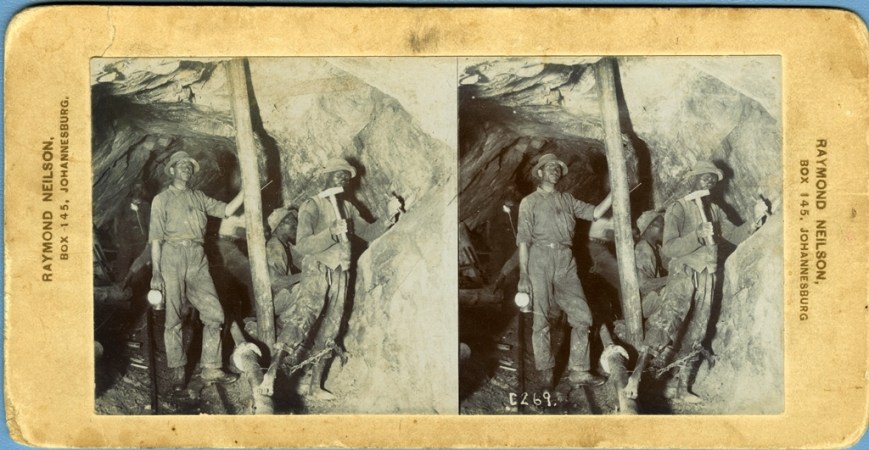

“bared life” – looking at stereographs of south african miners produced in the early 1900s (rosemary lombard, 2014)

This is a research paper I wrote in 2014 for “The Public Life of the Image”, an MPhil course offered through the Centre for African Studies at the University of Cape Town.

“[T]he striking mine workers at Marikana have become spectacularised. It is a stark reminder that the mine worker, a modern subject of capitalism, in these parts of the world is also the product of a colonial encounter.”

— Suren Pillay (2014)

“We need to understand how photography works within everyday life in advanced industrial societies: the problem is one of materialist cultural history rather than art history.”

— Allan Sekula (2003)

__

I pick up the odd wood and metal contraption. This is a stereoscope, I am told. It feels old, in the sense that there is a certain worn patina about it, and a non-utilitarian elegance to the turned wood and decoration, though not as if it were an expensive piece – just as if it came from an era where there was time for embellishment. It feels cheaply put together, mass-produced and flimsy as opposed to delicate, the engraving detail of the tinny sheet metal rather rough, the fit of the one piece as it glides through the other somewhat rickety in my hands.

From two elevations, a stereoscope almost identical to the one I used. Various kinds were devised in the 19th century. The particular hand-held variety, of oak, tin, glass and velvet depicted here dates back to 1901, Based on a design by the inventor Oliver Wendell Holmes, it is perhaps the most readily available and simplest model.

I reach for the pile of faded stereographs; flipping through them slowly. There are 24, picked up in an antique shop in an arcade off Cape Town’s Long Street together with the viewing device. A stereograph is composed of two photographs of the same subject taken from slightly different angles. When placed in the stereoscope’s wire holder, and viewed through the eyeholes, an illusion of perspective and depth is achieved as the two images appear to combine through a trick of parallax.

Susan Sontag remarks that “[p]hotographs, which cannot themselves explain anything, are inexhaustible invitations to deduction, speculation, and fantasy”2. And Allan Sekula calls the photograph an “incomplete utterance, a message that depends on some external matrix of conditions and presuppositions for its readability. That is, the meaning of any photographic message is necessarily context determined”3. In what follows, while unable to offer definitive conclusions, I will look more closely at 2 out of these 24 pictures and, through a contextual discussion, attempt to unpack a few aspects of the complex relationships of photography with its subjects and also with public circulation.

Each thick, oblong card with its rounded, scuffed edges discoloured by age has two seemingly identical images on it, side by side, and is embossed with the name of what I guess must have been the photographer or printing studio’s name in gold down the margin: “RAYMOND NEILSON, BOX 145, JOHANNESBURG”. The images depict miners underground. Some are very faded, to the extent that the figures in them appear featureless and ghostly. There is virtually no annotation on most of the photos. On just a few of them, spidery white handwriting on the photo itself, as if scratched into the negative before it was printed, announces the name of the machinery or activity in the picture and the name of the mine: “Crown Mines”.

I pick up the first card, slot it into the stereoscope, and peer through the device. On the left of the two images, the writing announces: “Ingersoll hammer drill cutting box hole. C215. Crown Mines.”

I slide the holder backwards and forwards along the wooden shaft to focus. I’m seeing two images, nothing remarkable, until suddenly, at a precise point on the axis, the images coalesce into one, three-dimensional. The experience is that of a gestalt switch, the optical illusion uncanny. I blink hard. It’s still there. It feels magical, as if the figures in the photos are stepping right out of the card towards me. Their eyes stare into mine through over a century of time, gleaming white out of dirty, sweaty faces.

Startlingly tangible, here stand two young white men in a mine shaft, scarcely out of their teens, leaning against rock, each with a hand on a hip and a jauntily cocked hat. They are very young… yet very old too, I immediately think: definitely dead now; and perhaps dead soon after the picture was taken, living at risk, killed in a rock fall or in World War One. A pang of indefinable emotion hits. I am amazed at how powerfully this image has flooded my imagination. Even with the difficult viewing process, the effect is astonishing.

I am reminded of Susan Sontag’s contention that all photographs are memento mori: “To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt”5.

I also notice that the trick of parallax (and concurrently, the evocativeness) works most pronouncedly on the figures in the foreground, probably due to the camera angle and vanishing points of the perspective. Behind the two white youngsters, almost fading into the darkness, is a black man, holding up a drill over all of their heads that seems to penetrate the tunnel of rock in which they are suspended.

He appears to have moved during the shot as his face is blurred. This could also be due to the low light in the shaft. Though he is looking straight at me, I can’t connect with him like I do with the figures in front. He is very much in the background, a presence without substance. The way the photo was set up and taken has placed him in that position, and this viewpoint is indelible, no matter how hard I try to look past it.

There is no writing on this one except for what seems to be a reference number: “C269”. The figure in the foreground is a black man, miming work with a mallet and chisel against the rock face, though clearly standing very still for the shot, as he is perfectly in focus, his sceptical gaze on us, a sharp shadow thrown on the rock behind him. This is no ordinary lamp light: it seems clear that these pictures have been professionally illumined by the photographer, perhaps using magnesium flares, because these shots definitely predate flash photography.

To the man with the chisel’s left stands a white man, face dark with dirt. He is holding a lamp in one hand, and his other grasps a support pile which bisects the shaft and also the photo. Tight-jawed, he stares beyond us, his eyes preoccupied, glazed over. Behind the two men in the foreground, there are more men – parts of two, perhaps three workers can be seen, one a black man crouched down at the rock face behind the man with the chisel.

What strikes me most trenchantly about this picture — the punctum, after Barthes7 — is the man with the chisel’s bare feet. He is at work in an extremely hazardous environment without shoes. Looking at all the photographs, every white worker is wearing boots, but there are several pictures where it is visible that many of the black workers are barefoot.

This is shocking visual evidence of an exploitative industry which does not take its workers’ safety seriously: these men are placed at incredible risk without the provision of adequate protective attire: none have hard protection for their heads, and black workers are without shoes. Men not deemed worthy of protection are, by inference, expendable. From these photos, one surmises that black lives are more dispensable than white.

I am really curious to find out more about these pictures. Perhaps the visual evidence here is echoed in literature? Perhaps they can tell us things the literature does not?

Who were these people posing? There is nothing on the back of the photos. No captions, no dates. Who was the photographer? For what purpose were these pictures being taken? The lack of answers to these most mundane of questions lends the photos an uncanny, almost spectral quality.

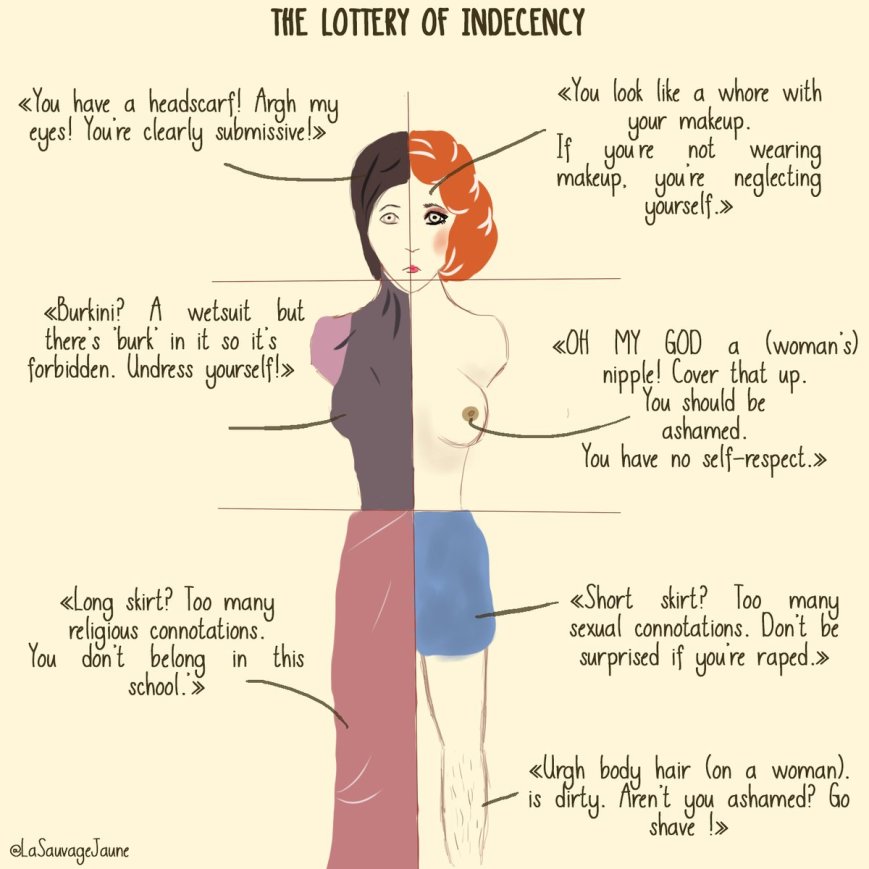

the lottery of indecency (2016)

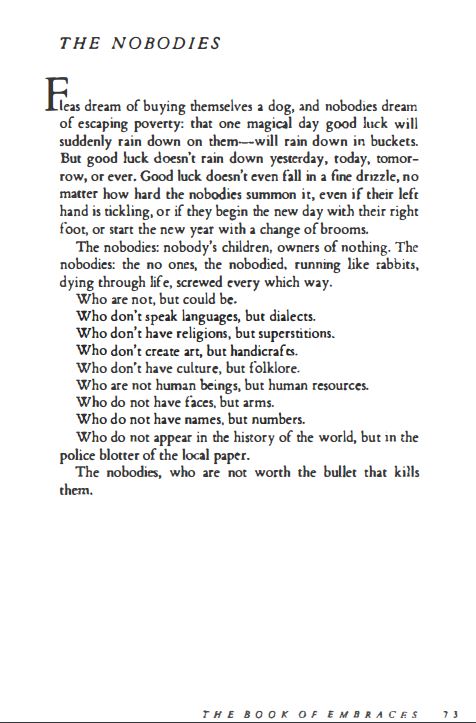

eduardo galeano – the nobodies (1991)

pharmakon interview (2015)

Great Interview with Margaret Chardiet AKA “Pharmakon” in Santiago, Chile, September 02, 2015, for her South American Tour “Sacred Bones”.

pharmakon – bestial burden (short film, 2014)

Directed by: Nina Hartmann and Margaret Chardiet.

Four days before New York noise musician Margaret Chardiet was supposed to leave for her first European tour as Pharmakon, she had a medical emergency which resulted in a major surgery. Suddenly, instead of getting on a plane, she was bedridden for three weeks, missing an organ.

“After seeing internal photographs taken during the surgery, I became hyperaware of the complex network of systems just beneath the skin, any of which were liable to fail or falter at any time,” Chardiet said. “It all happened so fast and unexpectedly that my mind took a while to catch up to the reality of my recovery. I felt a widening divide between my physical and mental self. It was as though my body had betrayed me, acting as a separate entity from my consciousness. I thought of my corporeal body anthropomorphically, with a will or intent of its own, outside of my will’s control, and seeking to sabotage. I began to explore the idea of the conscious mind as a stranger inside an autonomous vessel, and the tension that exists between these two versions of the self.”

Consumed by these ideas, and unable to leave her bed, Chardiet occupied herself by writing the lyrics and music that would become Bestial Burden, the second Pharmakon LP for Sacred Bones Records. The record is a harrowing collection of deeply personal industrial noise tracks, each one brimming with struggle and weighted with the intensity of Chardiet’s internal conflict.

Release date: 10/14/2014

Listen to the full album HERE.

pharmakon – abandon (2013/2016)

Margaret Chardiet describes her drive to make noise music as something akin to an exorcism where she is able to express her “deep-seated need/drive/urge/possession to reach other people and make them FEEL something [specifically] in uncomfortable/confrontational ways.” Engineered by Sean Ragon of Cult of Youth at his self-built recording studio Heaven Street, Abandon is Pharmakon’s first proper studio album and also her first widely distributed release.

Release date: 5/14/2016

Unlike other experimental projects, Pharmakon does not improvise when performing or recording. She is concise and exact; each song/movement is linear with a clear trajectory. Perhaps more than any other style of music, noise is a genre almost exclusively dominated by male performers. Spin Magazine is apt to point out that her,“perfectionism might explain why her recordings are few and far between—a rarity in a scene where noise bros are wont to puke out hour after endless hour of stoned basement jams into a limitless stream of limited-edition tapes. Her music may be as cuddly as a trepanning drill, but it’s also just as precise: She glowers in measured silence as often as she shrieks, and every serrated tone cuts straight to the bone, a carefully calibrated interplay between frequency and resistance.” The songs on this album were all written and recorded during a turbulent three month time period during which several fundamental life changes forced her to begin living in a completely new way and in a new space. She describes the lyrical themes of this album as being about, “Loss. Losing everything. Relinquishing control. Complete psychic abandon. Blind leaps of faith into the fire, walking out unscathed. Crawling out of the pit.”

edge of wrong presents “variations on the body” – 27 august 2016

Please join us for an evening of experimental live music hosted by the Edge of Wrong and featuring performances from pianist Coila-Leah Enderstein, electronic musician Daniel Gray, noise maestro Justin Allart and movement-based composition artists Aragorn23, Chantelle Gray and Amantha.

Please join us for an evening of experimental live music hosted by the Edge of Wrong and featuring performances from pianist Coila-Leah Enderstein, electronic musician Daniel Gray, noise maestro Justin Allart and movement-based composition artists Aragorn23, Chantelle Gray and Amantha.

Entrance is pay-what-you-can (recommended donation R50) and you can bring your own refreshments. Please make sure you arrive by 7:30 to minimise disruptions during performances.

___ ABOUT THE ARTISTS ___

Coila-Leah Enderstein is a classically trained pianist based in Cape Town. She’s into in experimental new music and interdisciplinary performance.

daniel gray is an artist from johannesburg and now lives in cape town. he is currently working as a high school maths teacher. he is interested in sound as image, dreams, collective improvisation and chance processes. in 2014-2016 he released an audiovisual album called “fantasmagoria”, a noise/peace album called “mssapessm”, took part in GIPCA live arts festival, performed around cape town, formed the now defunct subdwellers dj collective, started primitive ancestor records – a net label, to name a few of the many noisy endeavours. this will be the third edge of wrong event that he has participated in.

Justin Allart is a highly prolific experimental/noise musician who performs using a motley array of non-musical instruments. Expect sandpaper on turntables and effects pedals talking to themselves.

Aragorn23 is an experimental musician based in South Africa. His current work focuses on algorithmic and gestural composition and the use of the body as an instrument. He will be performing alongside collaborators Chantelle Gray and Amantha on the evening.

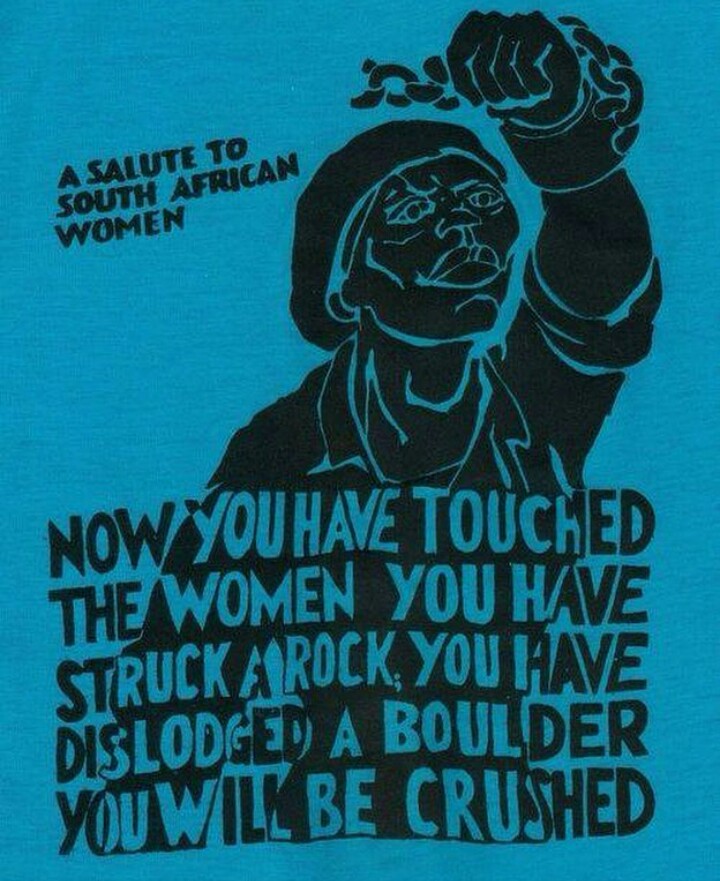

9 august

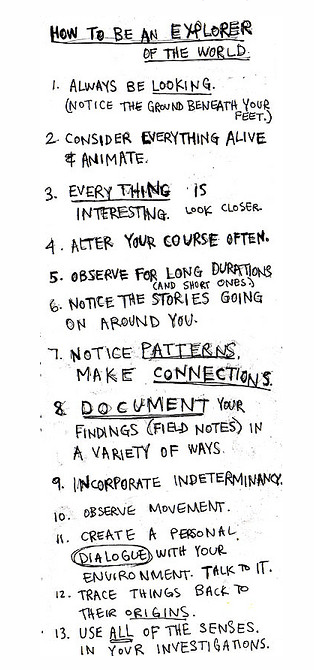

keri smith – how to be an explorer of the world

patti smith – kimberly (1975)

The wall is high, the black barn,

The babe in my arms in her swaddling clothes

And I know soon that the sky will split

And the planets will shift,

Balls of jade will drop and existence will stop.

Little sister, the sky is falling, I don’t mind, I don’t mind.

Little sister, the fates are calling on you.

Ah, here I stand again in this old ‘lectric whirlwind,

The sea rushes up my knees like flame

And I feel like just some misplaced Joan Of Arc

And the cause is you lookin’ up at me.

Oh baby, I remember when you were born,

It was dawn and the storm settled in my belly

And I rolled in the grass and I spit out the gas

And I lit a match and the void went flash

And the sky split and the planets hit,

Balls of jade dropped and existence stopped, stopped, stop, stop.

Little sister, the sky is falling, I don’t mind, I don’t mind.

Little sister, the fates are calling on you.

I was young ‘n crazy, so crazy I knew I could break through with you,

So with one hand I rocked you and with one heart I reached for you.

Ah, I knew your youth was for the takin’, fire on a mental plane,

So I ran through the fields as the bats with their baby vein faces

Burst from the barn and flames in a violent violet sky,

And I fell on my knees and pressed you against me.

Your soul was like a network of spittle,

Like glass balls movin’ in like cold streams of logic,

And I prayed as the lightning attacked

That something will make it go crack, something will make it go crack,

Something will make it go crack, something will make it go crack.

The palm trees fall into the sea,

It doesn’t matter much to me

As long as you’re safe, Kimberly.

And I can gaze deep

Into your starry eyes, baby, looking deep in your eyes, baby,

Looking deep in your eyes, baby, looking deep in your eyes, baby,

Into your starry eyes, oh.

Oh, in your starry eyes, baby,

Looking deep in your eyes, baby, looking deep in your eyes, baby, oh.

Oh, looking deep in your eyes, baby,

Into your starry eyes, baby, looking deep in your eyes, baby…

—

Simon Reynolds in a fascinating discussion with Patti Smith of her Horses album here.

note to self (live at the blah blah bar)

A poem by Louise Westerhout, accompanied by Lliezel Ellick (cello) and Rosemary Lombard (autoharp), performed on 28 July 2016 at the Blah Blah Bar’s Open Mouth night.

Next time we’ll make sure we find a venue where rude men at the bar are not entitled to talk through performances…

jacky bowring – a field guide to melancholy (2008)

“Melancholy is a twilight state; suffering melts into it and becomes a sombre joy. Melancholy is the pleasure of being sad.”

– Victor Hugo, Toilers of the Sea

Melancholy is ambivalent and contradictory. Although it seems at once a very familiar term, it is extraordinarily elusive and enigmatic. It is something found not only in humans – whether pathological, psychological, or a mere passing mood – but in landscapes, seasons, and sounds. They too can be melancholy. Batman, Pierrot, and Hamlet are all melancholic characters, with traits like darkness, unrequited longing, and genius or heroism. Twilight, autumn and minor chords are also melancholy, evoking poignancy and the passing of time.

How is melancholy defined? A Field Guide to Melancholy traces out some of the historic traditions of melancholy, most of which remain today, revealing it to be an incredibly complex term. Samuel Johnson’s definition, in his eighteenth century Dictionary of the English Language, reveals melancholy’s multi-faceted nature was already well established by then: ‘A disease, supposed to proceed from a redundance of black bile; a kind of madness, in which the mind is always fixed on one object; a gloomy, pensive, discontented temper.’2 All of these aspects – disease, madness and temperament – continue to coalesce in the concept of melancholy, and rather than seeking a definitive definition or chronology, or a discipline-specific account, this book embraces contradiction and paradox: the very kernel of melancholy itself.

As an explicit promotion of the ideal of melancholy, the Field Guide extols the benefits of the pursuit of sadness, and questions the obsession with happiness in contemporary society. Rather than seeking an ‘architecture of happiness’, or resorting to Prozac-with-everything, it is proposed that melancholy is not a negative emotion, which for much of history it wasn’t – it was a desirable condition, sought for its ‘sweetness’ and intensity. It remains an important point of balance – a counter to the ‘loss of sadness’. Not grief, not mourning, not sorrow, yet all of those things.

Melancholy is profoundly interdisciplinary, and ranges across fields as diverse as medicine, literature, art, design, psychology and philosophy. It is over two millennia old as a concept, and its development predates the emergence of disciplines.While similarly enduring concepts have also been tackled by a breadth of disciplines such as philosophy, art and literature, melancholy alone extends across the spectrum of arts and sciences, with significant discourses in fields like psychiatry, as much as in art. Concepts with such an extensive period of development (the idea of ‘beauty’ for example) tend to go through a process of metamorphosis and end up meaning something distinctly different.3 Melancholy has been surprisingly stable. Despite the depth and breadth of investigation, the questions, ideas and contradictions which form the ‘constellation’4 of melancholy today are not dramatically different from those at any time in its history. There is a sense that, as psychoanalytical theorist Julia Kristeva puts it, melancholy is ‘essential and trans-historical’.5

Melancholy is a central characteristic of the human condition, and Hildegard of Bingen, the twelfth century abbess and mystic, believed it to have been formed at the moment that Adam sinned in taking the apple – when melancholy ‘curdled in his blood’.6 Modern day Slovenian philosopher, Slavoj Žižek, also positions melancholy, and its concern with loss and longing, at the very heart of the human condition, stating ‘melancholy (disappointment with all positive, empirical objects, none of which can satisfy our desire) is in fact the beginning of philosophy.’7

The complexity of the idea of melancholy means that it has oscillated between attempts to define it scientifically, and its embodiment within a more poetic ideal. As a very coarse generalisation, the scientific/psychological underpinnings of melancholy dominated the early period, from the late centuries BC when ideas on medicine were being formulated, while in later, mainly post-medieval times, the literary ideal became more significant. In recent decades, the rise of psychiatry has re-emphasised the scientific dimensions of melancholy. It was never a case of either/or, however, and both ideals, along with a multitude of other colourings, have persisted through history.

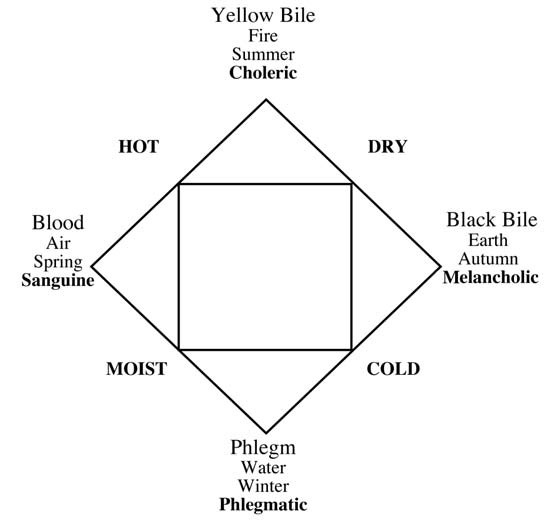

The essential nature of melancholy as a bodily as well as a purely mental state is grounded in the foundation of ideas on physiology; that it somehow relates to the body itself. These ideas are rooted in the ancient notion of ‘humours’. In Greek and Roman times humoralism was the foundation for an understanding of physiology, with the four humours ruling the body’s characteristics.

Phlegm, blood, yellow bile and black bile were believed to be the four governing elements, and each was ascribed to particular seasons, elements and temperaments. This can be expressed via a tetrad, or four-cornered diagram.

The Four Humours, adapted from Henry E Sigerist (1961) “A History of Medicine”, 2 vols New York: Oxford University Press, 2:232

The four-part divisions of temperament were echoed in a number of ways, as in the work of Alkindus, the ninth century Arab philosopher, who aligned the times of the day with particular dispositions. The tetrad could therefore be further embellished, with the first quarter of the day sanguine, second choleric, third melancholic and finally phlegmatic. Astrological allegiances reinforce the idea of four quadrants, so that Jupiter is sanguine, Mars choleric, Saturn is melancholy, and the moon or Venus is phlegmatic. The organs, too, are associated with the points of the humoric tetrad, with the liver sanguine, the gall bladder choleric, the spleen melancholic, and the brain/ lungs phlegmatic.

Melancholy, then, is associated with twilight, autumn, earth, the spleen, coldness and dryness, and the planet Saturn. All of these elements weave in and out of the history of melancholy, appearing in mythology, astrology, medicine, literature and art.The complementary humours and temperaments were sometimes hypothesised as balances, so that the opposite of one might be introduced as a remedy for an excess of another. For melancholy, the introduction of sanguine elements – blood, air and warmth – could counter the darkness. This could also work at an astrological level, as in the appearance of the magic square of Jupiter on the wall behind Albrecht Dürer’s iconic engraving Melencolia I, (1514) – the sign of Jupiter to introduce a sanguine balance to the saturnine melancholy angel.

In this early phase of the development of humoral thinking a key tension arose, as on one hand it was devised as a means of establishing degrees of wellness, but on the other it was a system of types of disposition. As Klibansky, Panofsky and Saxl put it, there were two quite different meanings to the terms sanguine, choleric, phlegmatic and melancholy, as either ‘pathological states or constitutional aptitudes’.9 Melancholy became far more connected with the idea of illness than the other temperaments, and was considered a ‘special problem’.

The blurry boundary between an illness and a mere temperament was a result of the fact that many of the symptoms of ‘melancholia’ were mental, and thus difficult to objectify, unlike something as apparent as a disfigurement or wound. The theory of the humours morphed into psychology and physiognomy, with particular traits or appearances associated with each temperament.

Melancholy was aligned with ‘the lisping, the bald, the stuttering and the hirsute’, and ‘emotional disturbances’ were considered as indicators of ‘mental melancholy’.10 Hippocrates in his Aphorismata, or ‘Aphorisms’, in 400 BC noted, ‘Constant anxiety and depression are signs of melancholy.’ Two centuries later the physician Galen, in an uncharacteristically succinct summation, noted that Hippocrates was ‘right in summing up all melancholy symptoms in the two following: Fear and Depression.’11

The foundations of the ideas on melancholy are fraught with complexity and contradiction, and this signals the beginning of a legacy of richness and debate. We have a love-hate relationship with melancholy, recognising its potential, yet fearing its connotations. What is needed is some kind of guide book, to know how to recognise it, where to find it – akin to the Observer’s Guides, the Blue Guides, or Gavin Pretor-Pinney’s The Cloudspotter’s Guide. Yet, to attempt to write a guide to such an amorphous concept as melancholy is overwhelmingly impossible, such is the breadth and depth of the topic, the disciplinary territories, the disputes, and the extensive creative outpourings. There is a tremendous sense of the infinite, like staring at stars, or at a room full of files, a daunting multitude. The approach is, therefore, to adopt the notion of the ‘constellation’, and to plot various points and co-ordinates, a join-the-dots approach to exploration which roams far and wide, and connects ideas and examples in a way which seeks new combinations and sometimes unexpected juxtapositions.

A Field Guide to Melancholy is therefore in itself a melancholic enterprise: for the writer, and the reader, the very idea of a ‘field guide’ to something so contradictory, so elusive, embodies the impossibility and futility that is central to melancholy’s yearning. Yet, it is this intangible, potent possibility which creates melancholy’s magnetism, recalling Joseph Campbell’s version of the Buddhist advice to “joyfully participate in the sorrows of the world”.12

Notes

1. Victor Hugo, Toilers of the Sea, vol. 3, p.159.

2. Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language, p.458, emphasis mine.

3. This constant shift in the development of concepts is well-illustrated by Umberto Eco (ed) (2004) History of Beauty, New York: Rizzoli, and his recent (2007) On Ugliness, New York: Rizzoli.

4. The term ‘constellation’ is Giorgio Agamben’s, and captures the sense of melancholy’s persistence as a collection of ideas, rather than one simple definition. See Giorgio Agamben, Stanzas:Word and Phantasm in Western Culture, p.19.

5. Julia Kristeva, Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia, p.258.

6. Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky and Fritz Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion and Art, p.79.

7. Slavoj Žižek, Did Somebody say Totalitarianism? Five Interventions on the (Mis)use of a Notion, p.148.

8. In Stanley W Jackson (1986), Melancholia and Depression: From Hippocratic Times to Modern Times, p.9.

9. Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky and Fritz Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion and Art, p.12.

10. ibid, p.15.

11. ibid, p.15, and n.42.

12. A phrase used by Campbell in his lectures, for example on the DVD Joseph Campbell (1998) Sukhavati. Acacia.

__

Excerpted from the introduction to Jacky Bowring’s A Field Guide to Melancholy, Oldcastle Books, 2008.

hera lindsay bird – keats is dead so fuck me from behind (2016)

Keats is dead so fuck me from behind

Keats is dead so fuck me from behind

Slowly and with carnal purpose

Some black midwinter afternoon

While all the children are walking home from school

Peel my stockings down with your teeth

Coleridge is dead and Auden too

Of laughing in an overcoat

Shelley died at sea and his heart wouldn’t burn

& Wordsworth……………………………………………..

They never found his body

His widow mad with grief, hammering nails into an empty meadow

Byron, Whitman, our dog crushed by the garage door

Finger me slowly

In the snowscape of your childhood

Our dead floating just below the surface of the earth

Bend me over like a substitute teacher

& pump me full of shivering arrows

O emotional vulnerability

Bosnian folk-song, birds in the chimney

Tell me what you love when you think I’m not listening

Wallace Stevens’s mother is calling him in for dinner

But he’s not coming, he’s dead too, he died sixty years ago

And nobody cared at his funeral

Life is real

And the days burn off like leopard print

Nobody, not even the dead can tell me what to do

Eat my pussy from behind

Bill Manhire’s not getting any younger

__

Read an interview with Hera Lindsay Bird at The Spinoff.

akira rabelais – eisoptrophobia (2001)

Akira Rabelais, one of my best Myspace discoveries – remember that strange place? I love this video, too, which was not available back then – one simply couldn’t stream hour-long films online. Get the album Eisoptrophobia (which is a term for the fear of one’s own image in reflection) HERE.

“i made a film that you will never see” (2015)

A short film about Michiel Kruger, who despite being blind, has set and broken various sports records the last 56 years. At the age of 70 he still holds 2 world records and runs a piano tuning business in Bloemfontein.

Director – Elmi Badenhorst

Camera and Edit – Jaco Bouwer

Music Composition – Braam Du Toit

Script and concept – Annelize Frost and Elmi Badenhorst

Ruan Scott – Subtitles