Category Archives: history

my first mixtape

Something I wrote in 2004 (You can listen to the mixtape here as you read.)

I remember being happy and carefree until about the year I turned 10. That was the year everyone around me became aware of something called “coolness”. It seemed you had to do certain things a certain way to be deemed “cool”. It didn’t make much sense to me. I collected stamps and pressed indigenous flowers. The other girls were really into pastel writing paper (blank). I was in the school choir. I had takkies instead of hockey boots (I hated hockey; why waste my parents’ money?). I read voraciously — National Geographics, Rumer Godden, Lucy Maud Montgomery. There was always a queue to read the next Sweet Valley High that I never joined.

While others were playing handstands and kissing catchers, I liked to walk further out, past the squeals, put my sandwich out on the grass, lie down and wait for a yellow-billed kite to spy it. I loved to feel the wind from its wings as it swooped down right over me from way up high… in the next second, bird and morsel would be gone; a tiny shadow, a cry far, far out of reach.

Almost all my time inside and outside school was spent dreaming up elaborate, exotic worlds and cobbling approximations of them together from whatever was at hand: cardboard, tablecloths, our little red wagon, press-ganged siblings, pets. Some games took weeks. Gypsy caravans morphed into Voortrekker laagers morphed into hunter-gatherers in the Drakensberg morphed into refugee camps morphed into townships morphed into castles under siege. Ways of being that were other than mine held endless fascination for me; every scenario a mystery I longed to inhabit. Engrossed with historical detail, with exact measurements, with flavours and textures and smells, I would be nowhere but there in my head – not exactly germane to making flesh-and-blood friends. Maybe worst of all, though, when the teacher asked questions in class and I was actually paying attention, I would put up my hand and answer, or even disagree with her.

I found out that my differences did not endear me to others, did not interest them. In fact, the things that made me different made me actively UNcool. At first I didn’t really care, but then it started to hurt. I was frozen out, systematically. The nastiest kids used to make me cry. They would pass notes warning their cronies not to borrow my scissors because I had “AIDS”. This was 1987. We didn’t really know what it was, only that it was worse than leprosy… and the lepers we’d heard about at Sunday School were pretty abhorrent.

One day I punched a boy called Stuart Urquhart when he had kicked my school bag, put Prestik in my hair and called me “ginger”, “fatty” and “freckles” one too many times. So what, I had freckles (show me a redhead who doesn’t… I quite liked mine, and I always liked my hair), but “fatty” I couldn’t accept. (It stuck regardless though. Around 16 I was weighing all my food to make sure I knew how many kilojoules I was swallowing.) Stuart came off with a respectably-sized purple and yellow bruise. The teacher made me stay in at big break and beat chalkboard dusters while Stuart got on with “getting off” with girls behind the change rooms on the far side of the field, where the myopic staff member on duty couldn’t make out that there were boys on the girls’ side. It was a Belle & Sebastian song just waiting to happen.

(This is a Youtube playlist I made to go with this piece.)

Fast forward to a year or two later, when I discovered The Smiths, the Pixies, U2 and the House of Love through a mix tape copied for me by the Std 7 boy I (and everyone else, it seemed) had a devastating crush on. He saved my life. Inadvertently, of course. He was the minister’s son, a gymnast with beautiful arms. Sitting outside, vestigial and bored at the Std 5 leavers’ disco, I imagined those taut biceps encircling my pubescent torso, crushing my stonies to him, exquisite pain as we slow-danced to Richard Marx, eternal reverie in the fuggy November night…

“Whatever it takes, or how my heart breaks, I will be right here waiting for you.”

When, oh when, would a boy sing that to me? (Note to younger self: “Don’t hold your breath, girlie.”) Only one boy had ever been sweet (or brave?) enough to ask me to dance at the handful of parties to which I was invited. The time he did, it wasn’t a slow song. He wasn’t that sweet (or brave?). His name was Francis and he flapped his elbows like a chicken. I was staying outside. I hadn’t developed a sense of irony yet.

“Close your eyes, gimme your hand, darlin'” … “Lay a whisper on my pillow” … “Huh-ush, hush, keep it down now, voices carry…”

Back then, those numbers induced in me a wild yearning for a reason to empathise with the girls from my Pop Shop tapes, and an overwhelming sense of hopelessness that things were not moving in that direction. That was before I discovered The Smiths, Depeche Mode, The Cure, Tears for Fears. What? Bands who were singing about how I really felt, instead of what I would never be?! Singing, in fact, about the precise feeling of inadequacy that perfect pop had provoked in me! They left me standing alone with a smirk, instead of the sigh of an outcast. The relief I felt was immediate.

“Sheila take a, Sheila take a bow/ Boot the grime of this world in the crotch, dear/ Throw your homework onto the fire/ Go out and find the one you love”

I wished I’d brought my rollerskates that night. I wanted to glide away down the smooth, concrete walkways, eerie dark tunnels ringing silently with the monitors’ “No running on the corridors!” refrain, the illicit rumble of my wheels propelling me far from all the clammy paired-off hands and Bon Jovi… I slipped out across the moonlit playing fields, the dew muddying both pairs of roll-down lumo-pink and white nylon socks I was wearing, my black takkies squeaking with every step. Grasping the perimeter fence, I pressed my face against the diamond mesh until it patterned my cheeks, and the dog barking at me from across the road forced the preternatural image that had projected itself into the sky — the minister’s son, away at boarding school in ‘Maritzburg, straw boater cocked rakishly — to dissipate.

The crush passed, though not until after I had wasted more than a year of stupefying Fridays at youth group watching the blonde chicks compete for his attention. I never tried. I had learned that tragedy was also cool. And anyway, Morrissey said I was the one for him (fatty). Who needed 15-year-old zitfarms when you had Morrissey’s alabaster chest and bruised daffodils, and Robert Smith’s bleeding mouth? So hot. So beyond sex. So beyond my stupid suburban world.

I ditched the stamps and started collecting Melody Makers & NMEs with religious fervour. Plastered my room with Joy Division, Bowie, Bauhaus, Jim Morrison, Sinead o’ Connor, Jesus & Mary Chain posters. Cultivated a floppy fringe and faraway eyes. Whined for Docs. A couple of years on my mom would be despairing at the puddles of black kohl staining my pillow. Every day, regardless of Natal’s weather, I wore the darkest parts of my school uniform: the navy jersey and dark stockings. Every day, I packed the same cabbage salad in my lunchbox, skimping on the mayo, trying to suppress my burgeoning curves, to look tortured, sick, blank, cold, mechanical, monosyllabic. Like I was inside.

The new wave music in my head deflected everything irrelevant. And everything felt irrelevant. I could identify with nothing around me. With no one — certainly not white South Africa in 1993! The violence. The confusion. The fear. The news explained nothing. I could taste the lies.

“Ich möchte ein Eisbär sein/ Im kalten Polar/ Dann müßte ich nicht mehr schrei’n/ Alles wär’ so klar.”

“All we ever wanted was everything/ All we ever got was cold/ Get up, eat jelly, Sandwich bars and barbed wire/ Squash every week into a day.”

“I could turn and walk away, or I could fire the gun/ Staring at the sky, staring at the sun/ Whatever I do, it amounts to the same: Absolutely nothing/ I’m alive/ I’m dead/ I am the stranger/ Killing an Arab.”

“Me… I disconnect from you…”

“I belong to the blank generation, and I can take or leave it each time.”

“I see liberals; I am just a fashion accessory… La tristessa durera, scream to a si-i-igh, to a si-i-igh…”

“Rock ‘n’ roll is our epiphany: culture, alienation, boredom and despair,” the Manic Street Preachers howled. I was in love with fragile, callow Richey Manic, with the leather, leopard print and makeup. We scrawled copycat slogans on our Std 9 history teacher’s blackboard before class. Mr Mundell was a Springbok walker (yes, a competitive WALKER) with a tight arse and vindictive streak a mile wide towards any “non-athlete”, his term for anyone who preferred house plays to hayfever. We spent our time in his classes on Bismarck and the Cold War and Botha VS Smuts writing rainbow pages in advance for “forgetting” our P.E. kits. Notice I say “we”, for by then the other angry girls in dark stockings had deigned to notice me. They were rebels. They’d nicked the template from their elder sisters who’d been in London.

Penny and Olwen were in love with their horses, and also with Dave Gahan and Brett Anderson. They had tails: long, snarled strands of hair that they had to keep rolled up and clipped under the other short hair to avoid being bust. When they got bored with those, they got undercuts. Anything to cause shit, to push the limits, to be different. I didn’t really get the point of that at high school. I had my mom do me a tight plait down my back most days. I made her do it over if it wasn’t perfect.

I tagged along with them, mostly for the music I could sponge off their connections. Penny had given me the Stone Roses record her sister bought her in London, for example. She’d scorned it cos it was “too pop”. She couldn’t see that part of its brilliance lay in the way the shambling prettiness cloaked the meticulous cruelty beneath:

“You’ve been bought and paid/ You’re a whore and a slave/ Your dark star holy shrine/ Come taste the end, you’re mine/ Here he comes/ Got no questions, got no love/ I’m throwing stones at you man/ I want you black and blue and/ I’m gonna make you bleed/ Gonna bring you down to your knees/ Bye bye badman/ Ooh, bye bye/ I’ve got a bad intention/ I intend to/ Knock you down/ These stones I throw/ Oh these French kisses/ Are the only way I’ve found…”

Swigging vodka and crème soda out of a juice bottle under the stands on Sports Day, keeping cave while they smoked, I couldn’t quite buy in to group rebellion. Drinking was fun. Cigarettes were siff. Dagga was a chance I was nervous of taking. I heard rumours that it could make you schizo. I already doubted my sanity too often. Also, I was pretty sure dagga definitely killed brain cells, and, well, I was coming top in the standard, and my parents expected me to continue doing so… My parents were the only people in the world I knew really did love me. Didn’t mean we liked each other much but I felt like I shouldn’t fuck that up…

Rewind a couple of years again: “You can all just kiss off into the air/ behind my back I can see them stare/ They’ll hurt me bad, but I won’t mind/ They’ll hurt me bad, they do it all the time, yeah, yeah, they do it all the time…”

The Violent Femmes! Never had I heard anything like them! Pasty, whiny smalltown nerds. They wrote lonely, ugly songs, about masturbation and Jesus and killing your daughters and wanting to fuck black girls. They broke the rules in a way I could dig. They broke them because they had to. But what really got me was the rock ‘n’ roll. Deadpan-venomous-breakneck-shake-a-chicken-rock’n’roll, baybeh. The fattest, twangiest bass… and a marimba! I wanted to be defiled! I hadn’t felt like dancing this much since I was about 9 or 10 and Dad used to stick on the Beatles’ Red Album for us when it was raining and we couldn’t play outside.

It was in a marquee on the beach at Kenton-on-Sea in the Eastern Cape that I noticed the first boy I would ever kiss watching me, kinda slo-mo headbanging to “American Music”. I remember he seemed passably cute. He lurched over, wordlessly, and pulled me close. Dizzy from my Cure-style flailings and a couple of Hunter’s Golds, I collapsed on top of him on a hay bale and his tongue found mouth. It busied itself deep in my nonplussed oral cavity for a while. It was all a bit too gross to feel like the miracle I had anticipated for years, but boy was I stoked. My necklace popped undone. Tiny, cold beads rolled down between my breasts, between my shoulder blades, adding to the strange, electric shivers as the foreign hand inched up, up under my Rattle & Hum t-shirt, fumbling round to the front. I think he pulled away because he had to burp.

His plaque was flavoured with curdled Black Label and zol, and the rest of him with that purple Ego deodorant – what was it called? Bahama Mist? Afterwards, back from my holiday, I would go into Spar with my mom, loiter around the mens’ toiletries while she was in another aisle, spray Bahama Mist nonchalantly into the lid, take a hit of sweaty rapture on my isle of romance, over and over again.

I don’t recall a word he said. I forgot his name years ago. But his friend’s, who had set about ravishing my younger sister in similar fashion, is indelibly etched in my mind. It was Geoff. You see, for weeks afterwards she and I chanted the Pixies’ refrain, “Jefrey-with-one-ef-Jefrey”, when alluding to the escapade in front of Mom and Dad. We were convinced if they found out what naughty things we’d got up to right under their noses, we’d NEVER be allowed to go to parties unchaperoned again.

Jef was a surfer, a boarder at a boys’ high school in King William’s Town. Suave. Told us he had a mattress in the back of his bakkie. (HIS bakkie? How old were they??) We shat ourselves. When they staggered off to find more dop, we skedaddled home to my grandparents’ house via the most brightly lit street. Out of breath with giggles, we picked the straw from our tresses, only a little more relieved than regretful that we had been sensible. Ooh, but hadn’t they given us their phone numbers?! When we dialled them from a tickiebox next day we got the out-of-order tone. And making a getaway the night before, I had forgotten to retrieve my beloved velvet hat from whence it had tumbled as I fell into first base. The first brutal abandonment, and there’d be too many down the years to keep count.

“A sad fact widely known/ The most impassioned song to a lonely soul/ Is so easily outgrown/ But don’t forget the songs that made you smile/ And the songs that made you cry/ As you lay in awe on your bedroom floor/ And said ‘Oh! Oh! Smother me, Mother…’/ Yes, you’re older now and you’re a clever swine/ But they were the only ones who ever stood by you…/ I’m here with the cause; I’m holding the torch/ In the corner of your room, can you hear me? And when you’re dancing, and laughing, and finally living/ Hear my voice in your head and think of me kindly.”

I do, Steven Patrick, you whiny old git, every now and then I really do. And you can consider this one such paean of my gratitude to your ilk. (2004)

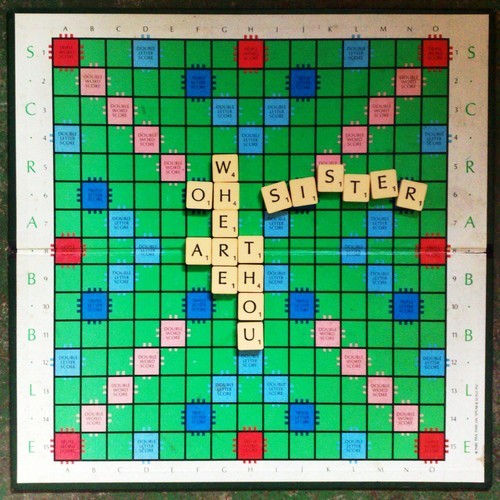

oh sister, where art thou? – bei mir bistu shein

lee morse – the music racket (1930)

One of three Vitaphone films Lee Morse starred in in 1930. She was a gifted songwriter, composer and band leader – Lee Morse and her Bluegrass Boys. The songs performed here are “Mailman Blues” and “In the Middle of the Night.” For a synopsis of the film, go HERE. For more biographical info, go HERE.

dezurik sisters – birmingham jail (1950)

duke ellington – the mooche

tale of tales (skazka skazok)

Astoundingly beautiful animation masterpiece by Yuri Norstein (USSR,1979, 28 min).

From Wikipedia:

Tale of Tales, like Tarkovsky’s Mirror, attempts to structure itself like a human memory. Memories are not recalled in neat chronological order; instead, they are recalled by the association of one thing with another, which means that any attempt to put memory on film cannot be told like a conventional narrative. The film is thus made up of a series of related sequences whose scenes are interspersed between each other. One of the primary themes involves war, with particular emphasis on the enormous losses the Soviet Union suffered on the Eastern Front during World War II. Several recurring characters and their interactions make up a large part of the film, such as the poet, the little girl and the bull, the little boy and the crows, the dancers and the soldiers, and especially the little grey wolf (Russian: се́ренький волчо́к, syeryenkiy volchok). Another symbol connecting nearly all of these different themes are green apples (which may symbolise life, hope, or potential).

Yuriy Norshteyn wrote in Iskusstvo Kino magazine that the film is “about simple concepts that give you the strength to live.”

anne michaels – phantom limbs (excerpt)

So much of the city

is our bodies. Places in us

old light still slants through to.

Places that no longer exist but are full of feeling,

like phantom limbs.

Even the city carries ruins in its heart.

Longs to be touched in places

only it remembers…

(from The Weight of Oranges / Miner’s Pond. McClelland & Stewart, 1997. p.86)

jayne cortez and the firespitters – there it is

ruth etting – i’m nobody’s baby (1927)

Rising to fame in the twenties and early thirties, Ruth Etting was renowned for her great beauty, her gorgeous voice and her tragic life. She starred on Broadway, made movies in Hollywood, married a mobster, had numerous hit-records, and was known as America’s Sweetheart of Song.

Born in David City, Nebraska on November 23, 1897, Ruth left home at seventeen for Chicago and art school. She got a job designing costumes at a night club called the Marigold Gardens and when the tenor got sick, she was pulled into the show since she was the only one who could sing low enough. That led to dancing in the chorus line and eventually featured solos.

By 1918 she was the featured vocalist at the club and the Gimp entered her life. A Chicago gangster, Moe Snyder married Ruth in 1922 and managed her career for the next two decades. Her numerous radio appearances during these years led to her becoming known as Chicago’s Sweetheart.

In 1926 she was discovered by a record company executive and immediately signed to an exclusive recording deal with Columbia Records, which led to nationwide exposure. Her early recordings were very straightforward in delivery. She later commented that “I sounded like a little girl on those records!” and insisted that her voice was actually much deeper than these recordings would lead one to believe.

In 1927 Ruth hit New York and she was an instant success. Irving Berlin suggested her for the Ziegfeld Follies and she was hired after Ziegfeld checked her ankles, not her voice. She appeared in the Follies of 1927. In 1929 she starred with Eddie Cantor in Whoopee! and in 1930 she made 135 appearances in Simple Simon with Ed Wynn. In 1931 she appeared in the very last Follies, shortly before Ziegfeld’s death.

Her blond hair and blue eyes and stunning voice all led to her being dubbed the Sweetheart of Columbia Records, America’s Radio Sweetheart, and finally America’s Sweetheart of Song. She began to experiment with tempo and phrasing during this period in her career. Her trademark was to change the tempo – alternating between normal tempo, half-time and double-time to create and maintain interest.

Ruth had over sixty hit recordings. Among her best in the Jazz Age are “Button Up Your Overcoat” and “Mean to Me” and, in the depression, “Ten Cents A Dance”. Her versions of “Shine on Harvest Moon”, “Let Me Call You Sweetheart”, “You Made Me Love You” and “Love Me or Leave Me” became her signature songs.

Next she headed to Hollywood and made a string of movie shorts and three full-length features. Her big break came in Roman Scandals with Eddie Cantor and Lucille Ball in a bit part. Then came Gift of Gab and Hips Hips Hooray.

It was in Hollywood that her loveless marriage finally fell apart. In 1937 Ruth fell for her accompanist and, in a rage, the Gimp shot him. The musician survived, Snyder went to jail and Ruth ended up divorcing him and marrying her true love, Meryl Alderman. But the scandal was too much for her career to survive. She made a few attempts at a comeback, but her days as America’s Sweetheart were over.

(Information from ruthetting.com, a site maintained by the granddaughter of one of Ruth Etting’s cousins.)

“imagination has turned into hallucination”

The following are excerpts from Vilém Flusser’s Towards a Philosophy of Photography (London: Reaktion Books, 2000).

The Image

Images are mediations between the world and human beings. Human beings ‘ex-ist’, i.e. the world is not immediately accessible to them and therefore images are needed to make it comprehensible. However, as soon as this happens, images come between the world and human beings. They are supposed to be maps but they turn into screens: Instead of representing the world, they obscure it until human beings’ lives finally become a function of the images they create. Human beings cease to decode the images and instead project them, still encoded, into the world ‘out there’, which meanwhile itself becomes like an image – a context of scenes, of state of things. This reversal of function of the image can be called ‘idolatry’; we can observe the process at work in the present day: The technical images currently all around us are in the process of magically reconstructing our ‘reality’ and turning it into a ‘global image scenario’. Essentially this is a question of ‘amnesia’. Human beings forget they created the images in order to orient themselves in the world. Since they are no longer able to decode them, their lives become a function of their own images: Imagination has turned into hallucination. (pp 9-10)

The struggle of writing against the image – historical consciousness against magic – runs throughout history. With writing, a new ability was born called ‘conceptual thinking’ which consisted of abstracting lines from surfaces, i.e. producing and decoding them. Conceptual thought is more abstract than imaginative thought as all dimensions are abstract from phenomena – with the exception of straight lines. Thus with the invention of writing, human beings took one step further back from the world. Texts do not signify the world; they signify the images they tear up. Hence, to decode texts means to discover the images signified by them. The intention of texts is to explain images, while that of concepts is to make ideas comprehensible. In this way, texts are a metacode of images.

This raises the question of the relationship between texts and images – a crucial question for history. In the medieval period, there appears to have been a struggle on the part of Christianity, faithful to the text, against idolaters or pagans; in modern times, a struggle on the part of textual science against image-bound ideologies. The struggle is a dialectical one. To the extent that Christianity struggled against paganism, it absorbed images and itself became pagan; to the extent that science struggled against ideologies, it absorbed ideas and itself became ideological. The explanation for this is as follows: Texts admittedly explain images in order to explain them away, but images also illuminate texts in order to make them comprehensible. Conceptual thinking admittedly analyze magical thought in order to clear it out of the way, but magical thought creeps into conceptual thought so as to bestow significance on it. In the course of this dialectical process, conceptual and imaginative thought mutually reinforce one another. In other words, images become more and more conceptual, texts more and more imaginative. Nowadays, the greatest conceptual abstraction is to be found in conceptual images (in computer images, for example); the greatest imagination is to be found in scientific texts. Thus, behind one’s back, the hierarchy of codes is overturned. Texts, originally a metacode of images, can themselves have images as a metacode.

That is not all, however. Writing itself is a mediation – just like images – and is subject to the same internal dialectic. In this way, it is not only externally in conflict with images but is also torn apart by an internal conflict. If it is the intention of writing to mediate between human beings and their images, it can also obscure images instead of representing them and insinuate itself between human beings and their images. If this happens, human beings become unable to decode their texts and reconstruct the images signified in them. If the texts, however, become incomprehensible as images, human beings’ lives become a function of their texts. There arises a state of ‘textolatry’ that is no less hallucinatory than idolatry. Examples of textolatry, of ‘faithfulness to the text’, are Christianity and Marxism. Texts are then projected into the world out there, and the world is experienced, known and evaluated as a function of these texts. A particularly impressive example of the incomprehensible nature of texts it provided nowadays by scientific discourse. Any ideas we may have of the scientific universe (signified by these texts) are unsound: If we do form ideas about scientific discourse, we have decoded it ‘wrongly’: anyone who tries to imagine anything, for example, using the equation of the theory of relativity, has not understood it. But as, in the end, all concepts signify ideas, the scientific, incomprehensible universe is an ’empty’ universe.

Textolatry reached a critical level in the nineteenth century. To be exact, with it history came to an end. History, in the precise meaning of the world, is a progressive transcoding of images into concepts, a progressive elucidation of ideas, a progressive disenchantment (taking the magic out of things), a progressive process of comprehension. If texts become incomprehensible, however, there is nothing left to explain, and history has come to an end. During this crisis of texts, technical images were invented: in order to make texts comprehensible again, to put them under a magic spell – to overcome the crisis of history. (pp 11 – 13)

++++++++++

To summarize: Photographs are received as objects without value that everyone can produce and that everyone can do what they like with. In fact, however, we are manipulated by photographs and programmed to act in a ritual fashion in the service of a feedback mechanism for the benefit of cameras. Photographs suppress our critical awareness in order to make us forget the mindless absurdity of the process of functionality, and it is only thanks to this suppression that functionality is possible at all. Thus photographs form a magic circle around us in the shape of the photographic universe. What we need is to break this circle. (pg 64)

++++++++++

Why a Philosophy of Photography is Necessary

With one exception: so-called experimental photographers – those photographers in the sense of the word intended here. They are conscious that image, apparatus, program and information are the basic problems that they have to come to terms with. They are in fact consciously attempting to create unpredictable information, i.e. to release themselves from the camera, and to place within the image something that is not in its program. They know they are playing against the camera. Yet even they are not conscious of the consequence of their practice: They are not aware that they are attempting to address the question of freedom in the context of apparatus in general. (pg 81)

A philosophy of photography is necessary for raising photographic practice to the level of consciousness, and this is again because this practice gives rise to a model of freedom in the post-industrial context in general. A philosophy of photography must reveal the fact that there is no place for human freedom within the area of automated, programmed and programming apparatuses, in order finally to show a way in which it is nevertheless possible to open up a space for freedom. The task of a philosophy of photography is to reflect upon this possibility of freedom – and thus its significance – in a world dominated by apparatuses; to reflect upon the ways in which, despite everything, it is possible for human beings to give significance to their lives in face of the chance necessity of death. Such a philosophy is necessary because it is the only form of revolution left open to us. (pp 81-82)

Read more excerpts from Flusser’s text HERE.

complete notes on the dissection of cadavers

More illustrations from the book HERE.

bob dylan – blind willie mctell

“Well, God is in His heaven

And we all want what’s His

But power and greed and corruptible seed

Seem to be all that there is

I’m gazing out the window

Of the St. James Hotel

And I know no one can sing the blues

Like Blind Willie McTell.”

Copyright © 1983 by Special Rider Music, from The Bootleg Series, Vol 1-3: Rare & Unreleased 1961-1991

howard zinn on war, violence and human nature

Howard Zinn talking about the environmental factors that influence aggression. Excerpt from You Can’t Be Neutral On a Moving Train, 2004 [DVD], available from firstrunfeatures.com.

alice in wonderland (w. w. young, 1915)

W. W. Young’s 1915 film of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. Starring Viola Savoy as Alice. Produced by The American Film Manufacturing Company (Flying A Studios) and released on 19 January 1915.

alice in wonderland (hepworth/stow, 1903)

Directed by two of the founders of British cinema, Cecil Hepworth and Percy Stow, its original running time of twelve minutes made the first cinematic adaptation of Lewis Carroll’s literary classic the longest running British film to date.The one remaining print has been restored by the BFI, and here it is, courtesy of Youtube.

Alice in Wonderland was clearly made for cinema goers who had already read the book, hence describing this version of Alice in Wonderland as a literary adaptation in the modern understanding of the term may be misleading (without prior knowledge of the books, deciphering the events of the film would be quite difficult). Given the film’s length, it would be better to describe it as a series of vignettes from the book. It is perhaps this aspect of the film’s organisation that gives it a peculiar and slightly disjointed feel.

It is memorable for its use of special effects, clearly inspired by the likes of Georges Méliès and the Lumière Brothers.

Despite the BFI’s best efforts, the original reel of Alice in Wonderland was damaged to such an extent that the deterioration is quite clearly visible on the restored print. This however, only heightens the dreamlike atmosphere of the film. Combined with the fact that the film is not a ‘conventional narrative’, Alice in Wonderland can be seen as a forerunner for the works of surrealist filmmakers such as René Clair, Luis Buñuel and Jean Cocteau.

Read more about the film HERE.

baloji with konono n°1 – karibu ya bintou (english subtitles)

From the album Kinshasa Succursale (Crammed Discs, 2011)

Video shot in the streets of Kinshasa.

Electric thumb piano (likembé) played by Konono N°1, the legendary Congolese band whose junkyard sonics and trademark “Congotronics” sound has had a major influence on the electronic and indie rock scenes.

Directors: Spike and Jones

DOP: Nicolas Karakatsanis

Producer: Annemie Decorte (Dr. Film)

Styling: Ann Lauwerys

Mask: Katrien Matthys

More info:

http://www.baloji.com

http://www.crammed.be

die wonderwerker

Trailer for the new Katinka Heyns film Die Wonderwerker, based on the life of poet, lawyer, naturalist and morphine addict, Eugene Marais.

Released: 7th September 2012

Starring: Cobus Rossouw, Marius Weyers, Sandra Kotze, Dawid Minnaar, Elize Cawood, Anneke Weidemann, Kaz McFadden, Erica Wessels

Synopsis:

Eugene Marais was not only a remarkable poet and naturalist, but an extraordinary person whose life was a continuous source of drama and controversy. In 1908, he is a qualified lawyer who has just spent a solitary 2 years living amongst the baboons of the remote Waterberg; studying their habits.

On his way to Nylstroom, in the grip of a Malaria induced fever, he stops on a farm looking for drinking water. Observing his weakness and the seriousness of his illness, Gys van Rooyen and his wife Maria take him into their home to recover.

Maria leads an unfulfilled life and she is lonely. The forty year old Eugene Marais is attractive, charming and mysterious. She, as many women before her, falls in love with him. There are two others resident in the house, the Van Rooyen’s son Adriaan, and a seventeen year old adopted daughter Jane Brayshaw.

Twelve years earlier Marais’ young wife, Aletta, died giving birth to their only child, something he was never able to process. Jane is a striking embodiment of her. Gradually he realizes he is losing his heart to her. And she reciprocates. What further complicates matters is that the young Adriaan is himself smitten with Jane.

Eugene Marais’ secret demon is his morphine addiction. He is a high functioning addict- whose behaviour is only affected when he doesn’t use it. Maria discovers his secret. In an attempt to not only curb his addiction but also to assert control over him, she confiscates his morphine and begins rationing it back to him.

This leads to a love quadrangle, like a time bomb ticking. Inevitably ticking…

This Film is in Afrikaans with English subtitles.

great southern land

sezen aksu – hıdrellez (1997)

Turkish language version of the Roma song “Ederlezi”, made famous outside the Balkans via Goran Bregovic’s version in Emir Kusturica’s film, Time of the Gypsies.

The song got its name from Ederlezi (Turkish: Hıdırellez) which is a spring festival celebrated by Roma people in the Balkans, Turkey and elsewhere around the world.

From Wikipedia:

Hıdırellez or Hıdrellez (Turkish: Hıdrellez or Hıdırellez, Azerbaijani: Xıdır İlyas or Xıdır Nəbi, Crimean Tatar: Hıdırlez, Romani language: Ederlezi) is celebrated in Turkey and throughout the Turkic world as the day on which prophets Hızır (Al-Khidr) and Ilyas (Elijah) met on the earth. Hıdırellez starts on May 5 night and falls on May 6 in the Gregorian calendar and on April 23 in the Julian calendar. It celebrates the arrival of spring and is a religious holiday for the Alevi as well. Đurđevdan or the Feast of Saint George is the Christian variety of this spring festival celebrated throughout the Balkans, including Serbia and Bulgaria, notably in areas under the control of the Ottoman Empire by the end of the 16th century.

There are various theories about the origin of Hızır and Hıdırellez. Ceremonies and rituals were performed for various gods with the arrival of the spring or summer in Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Iran and other Mediterranean countries since ancient times. One widespread belief suggests that Hızır attained immortality by drinking the water of life. He often wanders the earth, especially in the spring, helping people in difficulty. People see him as a source of bounty and health, as the festival takes place in Spring, the time of new life.

English translation:

Spring has come,

I’ve tied a red pouch on a rose’s branch,

I’ve vowed a house with two rooms

In the name of a lover

The mountain is green, the branches are green

They’ve awakened for the bayram (festival day)

All hearts are happy

Only my fate is black

The scent of jonquils is everywhere,

It’s time.

This spring, I’m the only one

Whom the bayram has not affected

Don’t cry, Hıdrellez

Don’t cry for me

I’ve sowed pain, and instead of it,

Love will sprout, will sprout

In another spring.

He has neither a way (known) nor a trace

His face is not familiar

The long and short of it,

My wish from the God is love.

I don’t have anyone to love, I don’t have a partner

One more day has dawned.

O my star of luck,

Smile on me!

(Translation based on the one here; not sure how good it is!)

katibim (üsküdar’a gider iken) – my scribe (going to üsküdar) (1929)

Folk song, recorded in 1949 in Istanbul. Sung by Safiye Ayla. Played with violin, kanun, ud and clarinet. This recording is in the public domain. You can download it HERE.

Background

Üsküdar (Scottary), now a section of Istanbul on the Anatolian (Asian) side, used to be a village/town across the Bosphorus from Istanbul proper, where nursing began during the Crimean War (British and French assisted Turks against Russia, 1854-56).

There is much fascinating debate about the origins of this song. Whose Is This Song? is a documentary made about the subject by Adela Peeva in 2003. Here’s the blurb:

“In her search for the true origins of a haunting melody, the filmmaker travels to Turkey, Greece, Macedonia, Albania, Bosnia, Serbia and Bulgaria. The trip is filled with humour, suspense, tragedy and surprise as each country’s citizens passionately claim the song to be their own and can even furnish elaborate histories for its origins. The tune emerges again and again in different forms: as a love song, a religious hymn, a revolutionary anthem, and even a Scottish military march. The powerful emotions and stubborn nationalism raised by one song seem at times comical and other times, eerily telling. In a region besieged by ethnic hatred and war, what begins as a light-hearted investigation ends as a sociological and historical exploration of the deep misunderstandings between the people of the Balkans.”

You can watch the preview HERE.

Lyrics

Here’s a translation of the Turkish version’s lyrics (a compound I have made from various versions I found online), which have been credited in some places to Nuri Halil Poyraz (1885 – 1950) and Muzaffer Sarisozen (1899 – 1963):

On the way to Üsküdar, it started raining

My scribe (katip) wears a frock coat, its long skirt muddied

He has just woken from sleep: his eyes are languid

The scribe is mine; I am his; hands will intertwine

It looks so lovely on my scribe, that starched shirt of his

On the way to Üsküdar, I found a handkerchief

I filled the handkerchief with Turkish delight (lokum)

As I was looking for my helper, I found him next to me

The scribe is mine; I am his; what is it to others?

It looks so lovely on my clerk, that starched shirt of his.

Käthe Kollwitz (July 8, 1867 – April 22, 1945)

“I have never produced anything cold but always to some extent with my blood. I do not want to die…until I have faithfully made the most of my talent and cultivated the seed that was placed in me until the last small twig has grown. I am in the world to change the world.”

http://www.rogallery.com/Kollwitz/Kollwitz-bio.htm

http://www.spaightwoodgalleries.com/Pages/Kollwitz_self_portraits.html

metaphors for abandonment: exploring urban ruins

The photographs in this post are of an abandoned hot springs resort/health spa, taken by me in July 2009. The resort is situated in Aliwal North, a tiny town on the border of South Africa’s Free State and Eastern Cape provinces. During Victorian times, and continuing into the dark era of Apartheid, this settlement on the Orange River was a popular holiday destination (whose amenities would have been available to whites only). I was stuck here for several days following a car accident, so I went exploring. I was told by a local that the resort had fallen into disrepair only recently, in the past decade, due to mismanagement of the allocated maintenance funds. I wondered to what extent this might reflect a rejection of the resort’s oppressive past by its post-1994 custodians.

I share the fascination with documenting ruins and decay that is the subject of the following excerpt from the excellent blog, Archaeology and Material Culture:

An astounding number of web pages document abandoned materiality, encompassing a broad range of architectural spaces including asylums, bowling alleys,industrial sites, Cold War sites, and roadside motels as well as smaller things like pianosand even scale models of abandonment. This ruination lust is not simply the province of a small handful of visual artists, hipsters colonizing Detroit, or recalcitrant trespassers; instead, it invokes something that reaches far deeper socially, has international dimensions, extends well into the past, and reflects a deep-seated fascination with—if not apprehension of—abandonment. The question is what explains our apparently sudden collective fascination with abandonment, ruination, and decay. The answers are exceptionally complex and highly individual, but there seem to be some recurrent metaphors in these discourses.

For “urban explorers” (a term that might loosely include artists, photographers, archaeologists, and curious folks alike), such journeys seek out “abandoned, unseen, and off-limits” spaces that imagine ruination in a wide range of artistic, emotional, scholarly, and political forms. Many of these urban explorers and artists see themselves as visual historians, documenting the architectural and community heritage reflected in abandoned spaces. For instance, Jonathan Haeber’s urban exploration blog Bearings explains that “I’m just an eye. I’m just a camera. … An urban explorer is just a documentarian. … We only appreciate the creations that are overlooked. … It is what remains that is the democratic equivalent of a revolution.” Continue reading

the flower of seven colours

Cvetik Semicvetik (Flower of Seven Colours) is a beautiful Soviet children’s animation from 1948, based on a beloved folk tale about a little girl who receives a magic flower with seven free wishes from an old crone. None of her wishes leads to happiness, until the last wish, which she doesn’t use for herself, but for someone else. By making someone else happy, she is made happy too.

There are many different illustrated versions out there, but perhaps the most trippy one comes from the mind of Russian artist Benjamin Losin. Losin apparently illustrated two different versions of this book.

hoagy carmichael – stardust (original vocal version)

On October 31, 1927, Hoagy Carmichael and His Pals recorded Carmichael’s composition “Stardust” at the Gennett Records studio in Richmond, Indiana. Hoagy’s “pals,” Emil Seidel and His Orchestra, agreed to record the medium-tempo instrumental in between their Sunday evening and Monday matinee performances in Indianapolis, seventy miles away.

In 1928 Carmichael again recorded “Stardust,” this time with lyrics he had written, but Gennett rejected it because the instrumental had sold so poorly. The following year, at Mills Music, Mitchell Parish was asked to set lyrics to coworker Carmichael’s song. The result was the 1929 publication date of “Star Dust” with the music and lyrics we know today. The Mills publication changed the title slightly to “Star Dust” from “Stardust” as it was originally spelled.

This information taken from JazzStandards.com.

the romance of winds

There is a whirlwind in southern Morocco, the aajej, against which the fellahin defend themselves with knives. There is the africo, which has at times reached into the city of Rome. The alm, a fall wind out of Yugoslavia. The arifi, also christened aref or rifi, which scorches with numerous tongues. These are permanent winds that live in the present tense.

There are other, less constant winds that change direction, that can knock down horse and rider and realign themselves anticlockwise. The bist roz leaps into Afghanistan for 170 days, burying villages. There is the hot, dry ghibli from Tunis, which rolls and rolls and produces a nervous condition. The haboob — a Sudan dust storm that dresses in bright yellow walls a thousand metres high and is followed by rain. The harmattan, which blows and eventually drowns itself into the Atlantic. Imbat, a sea breeze in North Africa. Some winds that just sigh towards the sky. Night dust storms that come with the cold. The khamsin, a dust in Egypt from March to May, named after the Arabic word for ‘fifty,’ blooming for fifty days–the ninth plague of Egypt. The datoo out of Gibraltar, which carries fragrance.

There is also the ——, the secret wind of the desert, whose name was erased by a king after his son died within it. And the nafhat — a blast out of Arabia. The mezzar-ifoullousen — a violent and cold southwesterly known to Berbers as ‘that which plucks the fowls.’ The beshabar, a black and dry northeasterly out of the Caucasus, ‘black wind.’ The samiel from Turkey, ‘poison and wind,’ used often in battle. As well as the other ‘poison winds,’ the simoom, of North Africa, and the solano, whose dust plucks off rare petals, causing giddiness.

Other, private winds.

Travelling along the ground like a flood. Blasting off paint, throwing down telephone poles, transporting stones and statue heads. The harmattan blows across the Sahara filled with red dust, dust as fire, as flour, entering and coagulating in the locks of rifles. Mariners called this red wind the ‘sea of darkness.’ Red sand fogs out of the Sahara were deposited as far north as Cornwall and Devon, producing showers of mud so great this was also mistaken for blood. ‘Blood rains were widely reported in Portugal and Spain in 1901.’

There are always millions of tons of dust in the air, just as there are millions of cubes of air in the earth and more living flesh in the soil (worms, beetles, underground creatures) than there is grazing and existing on it. Herodotus records the death of various armies engulfed in the simoom who were never seen again. One nation was ‘so enraged by this evil wind that they declared war on it and marched out in full battle array, only to be rapidly and completely interred.

— Michael Ondaatje, from The English Patient.

schtumm!

Illustration done by Willy Pogany in 1914 for T. W. Rolleston’s Tale of Lohengrin,1914. You can download the whole book from HERE.

Lohengrin is a character in German Arthurian literature. His story, which first appears in Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival, is a version of the Knight of the Swan legend known from a variety of medieval sources.

The son of Parzival (Percival), Lohengrin is a knight of the Holy Grail sent in a boat pulled by swans to rescue a maiden, Elsa, who is the daughter of the Duke of Brabant, and who is forbidden to ask about his identity. At King Arthur’s command he is taken by a swan through the air to Mainz, where he fights for Elsa, overthrows her persecutor, and marries her. He then accompanies the emperor to fight against the Hungarians, and subsequently against the Saracens. On his return home to Cologne, Elsa, contrary to the prohibition, persists in asking him about his origin. After being asked a third time he tells her, but at that instant is carried away by the swan back to the Grail.

Wolfram’s story was expanded in two later romances. In 1848 Richard Wagner adapted the medieval tale into his popular opera Lohengrin, on which Rolleston based his book.

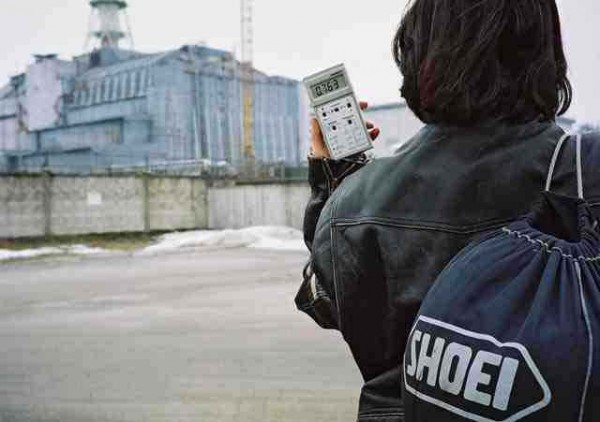

elena filatova – the serpent’s wall

Elena Filatova has created this intriguing site about the defensive walls around Kiev in the Ukraine. They were built before the Mongol invasion in the 12th Century and a huge resistance was mounted in WWII against the Germans there. It’s a fascinating read, despite her not-so-good English.

Elena and a bunch of friends spend loads of time digging for relics around Kiev. They take bikes and metal detectors and beers and camp out and play guitar at night, after digging until they drop in the daylight. They’re addicted to the thrill of unearthing old arrowheads and earrings and coins that go back thousands of years, or machine guns or helmets or grenades from massive, half-flooded concrete bunkers from the Second World War.

Elena, whose father was a nuclear physicist, also (apparently) rode through the Chernobyl ‘dead’ site on a fuckoff big motorbike, documenting the destruction that was left behind, including how the ‘liquidators’ were sent in to seal the site and how many died later as a result of massive exposure to radiation. It’s all on kidofspeed.com. There has been a lot of speculation on the Net that Elena didn’t actually ride through the Chernobyl zone on a bike. Some writers on sites like Wikipedia suspect her story is a hoax. But even if she did go as part of a tour, in a car, her photos are nevertheless real, and so are the stories they tell, for instance, of people who refused to leave, who have mostly since died… “I would rather die at home from radiation, than die in an unfamiliar place of home-sickness,” as one old man put it… Stories of an area of the earth that will be polluted for the next 48 000 years…

Elena, whose father was a nuclear physicist, also (apparently) rode through the Chernobyl ‘dead’ site on a fuckoff big motorbike, documenting the destruction that was left behind, including how the ‘liquidators’ were sent in to seal the site and how many died later as a result of massive exposure to radiation. It’s all on kidofspeed.com. There has been a lot of speculation on the Net that Elena didn’t actually ride through the Chernobyl zone on a bike. Some writers on sites like Wikipedia suspect her story is a hoax. But even if she did go as part of a tour, in a car, her photos are nevertheless real, and so are the stories they tell, for instance, of people who refused to leave, who have mostly since died… “I would rather die at home from radiation, than die in an unfamiliar place of home-sickness,” as one old man put it… Stories of an area of the earth that will be polluted for the next 48 000 years…

Elena has also documented experiences of Russian prisoners – you can find these on Echoes of Trapped Voices – with titles like “Shoveling diamonds up the arse of one’s own destiny”. If you do enough trawling on the Net, you’ll find she’s written about a host of topics, from the nuclear disaster in Japan to the London bombings. She is sure one fascinating, free, unusual hell of a woman.

history by robert lowell

clutching and close to fumbling all we had–

it is so dull and gruesome how we die,

unlike writing, life never finishes.

Abel was finished; death is not remote,

a flash-in-the-pan electrifies the skeptic,

his cows crowding like skulls against high-voltage wire,

his baby crying all night like a new machine.

As in our Bibles, white-faced, predatory,

the beautiful, mist-drunken hunter’s moon ascends–

a child could give it a face: two holes, two holes,

my eyes, my mouth, between them a skull’s no-nose–

O there’s a terrifying innocence in my face

drenched with the silver salvage of the mornfrost.

![22hr38min [photo: Niklas Zimmer]C-type print 120x99,4cm (Ed.3) and 60x49,7cm (Ed.7)](https://fleurmach.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/22hr38min-niklas-zimmer.jpg?w=869)