Chapter Eight from This Sex Which Is Not One, 1985. This text was originally published as “Le marche des femmes,” in Sessualita e politica, (Milan: Feltrinelli, 1978).

The society we know, our own culture, is based upon the exchange of women. Without the exchange of women, we are told, we would fall back into the anarchy (?) of the natural world, the randomness (?) of the animal kingdom. The passage into the social order, into the symbolic order, into order as such, is assured by the fact that men, or groups of men, circulate women among themselves, according to a rule known as the incest taboo.

Whatever familial form this prohibition may take in a given state of society, its signification has a much broader impact. It assures the foundation of the economic, social, and cultural order that has been ours for centuries.

Why exchange women? Because they are “scarce [commodities] . . . essential to the life of the group,” the anthropologist tells us.1 Why this characteristic of scarcity, given the biological equilibrium between male and female births? Because the “deep polygamous tendency, which exists among all men, always makes the number of available women seem insufficient. Let us add that even if there were as many women as men, these women would not be equally desirable … and that, by definition. . ., the most desirable women must form a minority. “2

Are men all equally desirable? Do women have no tendency toward polygamy? The good anthropologist does not raise such questions. A fortiori: why are men not objects of exchange among women? It is because women’s bodies – through their use, consumption, and circulation – provide for the condition making social life and culture possible, although they remain an unknown “infrastructure” of the elaboration of that social life and culture. The exploitation of the matter that has been sexualized female is so integral a part of our sociocultural horizon that there is no way to interpret it except within this horizon.

In still other words: all the systems of exchange that organize patriarchal societies and all the modalities of productive work that are recognized, valued, and rewarded in these societies are men’s business. The production of women, signs, and commodities is always referred back to men (when a man buys a girl, he “pays” the father or the brother, not the mother … ), and they always pass from one man to another, from one group of men to another. The work force is thus always assumed to be masculine, and “products” are objects to be used, objects of transaction among men alone.

Which means that the possibility of our social life, of our culture, depends upon a ho(m)mo-sexual monopoly? The law that orders our society is the exclusive valorization of men’s needs/desires, of exchanges among men. What the anthropologist calls the passage from nature to culture thus amounts to the institution of the reign of hom(m)o-sexuality. Not in an “immediate” practice, but in its “social” mediation. From this point on, patriarchal societies might be interpreted as societies functioning in the mode of “semblance.” The value of symbolic and imaginary productions is superimposed upon, and even substituted for, the value of relations of material, natural, and corporal (re)production.

From “The Sensualist”, Kōshoku Ichidai Otoko’s animated interpretation of the 17th century novel by Ihara Seikaku

In this new matrix of History, in which man begets man as his own likeness, wives, daughters, and sisters have value only in that they serve as the possibility of, and potential benefit in, relations among men. The use of and traffic in women subtend and uphold the reign of masculine hom(m)o-sexuality, even while they maintain that hom(m)o-sexuality in speculations, mirror games, identifications, and more or less rivalrous appropriations, which defer its real practice. Reigning everywhere, although prohibited in practice, hom(m)o-sexuality is played out through the bodies of women, matter, or sign, and heterosexuality has been up to now just an alibi for the smooth workings of man’s relations with himself, of relations among men.

Whose “sociocultural endogamy” excludes the participation of that other, so foreign to the social order: woman. Exogamy doubtless requires that one leave one’s family, tribe, or clan, in order to make alliances. All the same, it does not tolerate marriage with populations that are too far away, too far removed from the prevailing cultural rules. A sociocultural endogamy would thus forbid commerce with women. Men make commerce of them, but they do not enter into any exchanges with them. Is this perhaps all the more true because exogamy is an economic issue, perhaps even subtends economy as such? The exchange of women as goods accompanies and stimulates exchanges of other “wealth” among groups of men. The economy in both the narrow and the broad sense-that is in place in our societies thus requires that women lend themselves to alienation in consumption, and to exchanges in which they do not participate, and that men be exempt from being used and circulated like commodities.

*

Marx’s analysis of commodities as the elementary form of capitalist wealth can thus be understood as an interpretation of the status of woman in so-called partriarchal societies. The organization of such societies, and the operation of the symbolic system on which this organization is based-a symbolic system whose instrument and representative is the proper name: the name of the father, the name of God-contain in a nuclear form the developments that Marx defines as characteristic of a capitalist regime: the submission of “nature” to a “labor” on the part of men who thus constitute “nature” as use value and exchange value; the division of labor among private producer-owners who exchange their women-commodities among themselves, but also among producers and exploiters or exploitees of the social order; the standardization of women according to proper names that determine their equivalences; a tendency to accumulate wealth, that is, a tendency for the representatives of the most “proper” names-the leaders-to capitalize more women than the others; a progression of the social work of the symbolic toward greater and greater abstraction; and so forth.

To be sure, the means of production have evolved, new techniques have been developed, but it does seem that as soon as the father-man was assured of his reproductive power and had marked his products with his name, that is, from the very origin of private property and the patriarchal family, social exploitation occurred. In other words, all the social regimes of “History” are based upon the exploitation of one “class” of producers, namely, women. Whose reproductive use value (reproductive of children and of the labor force) and whose constitution as exchange value underwrite the symbolic order as such, without any compensation in kind going to them for that “work.” For such compensation would imply a double system of exchange, that is, a shattering of the monopolization of the proper name (and of what it signifies as appropriative power) by father-men.

Thus the social body would be redistributed into producer-subjects no longer functioning as commodities because they provided the standard of value for commodities, and into commodity objects that ensured the circulation of exchange without participating in it as subjects.

*

Let us now reconsider a few points (3) in Marx’s analysis of value that seem to describe the social status of women.

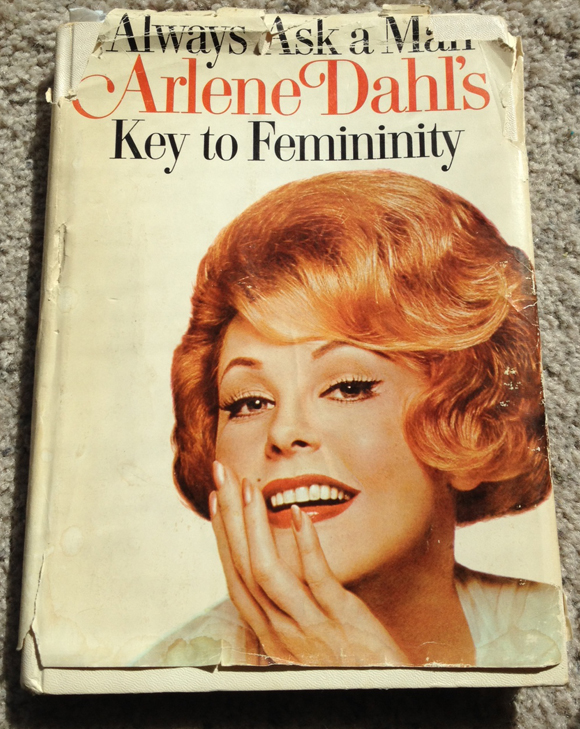

Wealth amounts to a subordination of the use of things to their accumulation. Then would the way women are used matter less than their number? The possession of a woman is certainly indispensable to man for the reproductive use value that she represents; but what he desires is to have them all. To “accumulate” them, to be able to count off his conquests, seductions, possessions, both sequentially and cumulatively, as measure or standard(s).

All but one? For if the series could be closed, value might well lie, as Marx says, in the relation among them rather than in the relation to a standard that remains external to them – whether gold or phallus.

The use made of women is thus of less value than their appropriation one by one. And their “usefulness” is not what counts the most. Woman’s price is not determined by the “properties” of her body-although her body constitutes the material support of that price.

But when women are exchanged, woman’s body must be treated as an abstraction. The exchange operation cannot take place in terms of some intrinsic, immanent value of the commodity.

It can only come about when two objects-two women are in a relation of equality with a third term that is neither the one nor the other. It is thus not as “women” that they are exchanged, but as women reduced to some common feature-their current price in gold, or phalluses-and of which they would represent a plus or minus quantity. Not a plus or a minus of feminine qualities, obviously. Since these qualities are abandoned in the long run to the needs of the consumer, woman has value on the market by virtue of one single quality: that of being a product of man’s “labor.”

On this basis, each one looks exactly like every other. They all have the same phantom-like reality. Metamorphosed in identical sublimations, samples of the same indistinguishable work, all these objects now manifest just one thing, namely, that in their production a force of human labor has been expended, that labor has accumulated in them. In their role as crystals of that common social substance, they are deemed to have value.

Liu Jianhua – ceramic

As commodities, women are thus two things at once: utilitarian objects and bearers of value. “They manifest themselves therefore as commodities, or have the form of commodities, only in so far as they have two forms, a physical or natural form, and a value form” (p. 55).

But “the reality of the value of commodities differs in respect from Dame Quickly, that we don’t know ‘where to have it”’ (ibid.). Woman, object of exchange, differs from woman, use value, in that one doesn’t know how to take (hold of) her, for since “the value of commodities is the very opposite of the coarse materiality of their substance, not an atom of matter enters into its composition. Turn and examine a single commodity, by itself, as we will. Yet in so far as it remains an object of value, it seems impossible to grasp it” (ibid.). The value of a woman always escapes: black continent, hole in the symbolic, breach in discourse . . . It is only in the operation of exchange among women that something of this-something enigmatic, to be sure-can be felt. Woman thus has value only in that she can be exchanged. In the passage from one to the other, something else finally exists beside the possible utility of the “coarseness” of her body. But this value is not found, is not recaptured, in her. It is only her measurement against a third term that remains external to her, and that makes it possible to compare her with another woman, that permits her to have a relation to another commodity in terms of an equivalence that remains foreign to both.

Women-as-commodities are thus subject to a schism that divides them into the categories of usefulness and exchange value; into matter-body and an envelope that is precious but impenetrable, ungraspable, and not susceptible to appropriation by women themselves; into private use and social use.

In order to have a relative value, a commodity has to be confronted with another commodity that serves as its equivalent.

Its value is never found to lie within itself And the fact that it is worth more or less is not its own doing but comes from that to which it may be equivalent. Its value is transcendent to itself, super-natural, ek-static.

In other words, for the commodity, there is no mirror that copies it so that it may be at once itself and its “own” reflection. One commodity cannot be mirrored in another, as man is mirrored in his fellow man. For when we are dealing with commodities the self-same, mirrored, is not “its” own likeness, contains nothing of its properties, its qualities, its “skin and hair.” The likeness here is only a measure expressing the fabricated character of the commodity, its trans-formation by man’s (social, symbolic) “labor.” The mirror that envelops and paralyzes the commodity specularizes, speculates (on) man’s “labor.” Commodities, women, are a mirror of value of and for man. In order to serve as such, they give up their bodies to men as the supporting material of specularization, of speculation. They yield to him their natural and social value as a locus of imprints, marks, and mirage of his activity.

Commodities among themselves are thus not equal, nor alike, nor different. They only become so when they are compared by and for man. And the prosopopoeia of the relation of commodities among themselves is a projection through which producers exchangers make them reenact before their eyes their operations of specula(riza)tion. Forgetting that in order to reflect (oneself), to speculate (oneself), it is necessary to be a “subject,” and that matter can serve as a support for speculation but cannot itself speculate in any way.

Thus, starting with the simplest relation of equivalence between commodities, starting with the possible exchange of women, the entire enigma of the money form-of the phallic function-is implied. That is, the appropriation-disappropriation by man, for man, of nature and its productive forces, insofar as a certain mirror now divides and travesties both nature and labor. Man endows the commodities he produces with a narcissism that blurs the seriousness of utility, of use.

Desire, as soon as there is exchange, “perverts” need. But that perversion will be attributed to commodities and to their alleged relations. Whereas they can have no relationships except from the perspective of speculating third parties.

The economy of exchange-of desire-is man’s business. For two reasons: the exchange takes place between masculine subjects, and it requires a plus-value added to the body of the commodity, a supplement which gives it a valuable form. That supplement will be found, Marx writes, in another commodity, whose use value becomes, from that point on, a standard of value.

But that surplus-value enjoyed by one of the commodities might vary: ‘Just as many a man strutting about in a gorgeous uniform counts for more than when in mufti” (p. 60). Or just as “A, for instance, cannot be ‘your majesty’ to B, unless at the same time majesty in B’s eyes assume the bodily form of A, and, what is more, with every new father of the people, changes its features, hair, and many other things besides” (ibid.).

Commodities – “things” produced – would thus have the respect due the uniform, majesty, paternal authority. And even God. “The fact that it is value, is made manifest by its equality with the coat, just as the sheep’s nature of a Christian is shown in his resemblance to the Lamb of God” (ibid.).

Commodities thus share in the cult of the father, and never stop striving to resemble, to copy, the one who is his representative. It is from that resemblance, from that imitation of what represents paternal authority, that commodities draw their value – for men. But it is upon commodities that the producers-exchangers bring to bear this power play. “We see, then, all that our analysis of the value of commodities has already told us, is told us by the linen itself, so soon as it comes into communication with another commodity, the coat. Only it betrays its thoughts in that language with which alone it is familiar, the language of commodities. In order to tell us that its own value is created by labour in its abstract character of human labour, it says that the coat, in so far as it is worth as much as the linen, and therefore is value, consists of the same labour as the linen. In order to inform us that its sublime reality as value is not the same as its buckram body, it says that value has the appearance of a coat, and consequently that so far as the linen is value, it and the coat are as like as two peas. We may here remark, that the language of commodities has, besides Hebrew, many other more or less correct dialects. The German ‘werthsein,’ to be worth, for instance, expresses in a less striking manner than the Romance verbs ‘valere,’ ‘valer,’ ‘valoir,’ that the equating of commodity B to commodity A, is commodity A’s own mode of expressing its value. Paris vaut bien une messe” (pp. 60-61).

So commodities speak. To be sure, mostly dialects and patois, languages hard for “subjects” to understand. The important thing is that they be preoccupied with their respective values, that their remarks confirm the exchangers’ plans for them. Continue reading →

Deep down inside, the Young-Girl has the personality of a tampon: she exemplifies all of the appropriate indifference, all of the necessary coldness demanded by the conditions of metropolitan life.

Deep down inside, the Young-Girl has the personality of a tampon: she exemplifies all of the appropriate indifference, all of the necessary coldness demanded by the conditions of metropolitan life.