Creation: good broken up into pieces and scattered throughout evil.

Creation: good broken up into pieces and scattered throughout evil.

Evil is limitless but it is not infinite. Only the infinite limits the limitless.

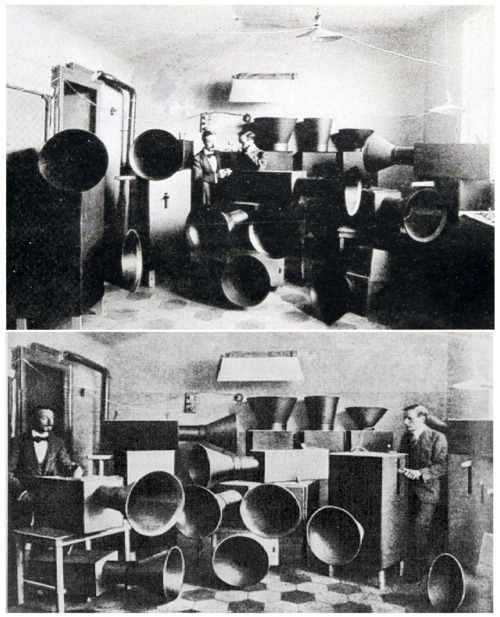

Monotony of evil: never anything new, everything about it is equivalent. Never anything real, everything about it is imaginary. It is because of this monotony that quantity plays so great a part. A host of women (Don Juan) or of men (Célimène), etc. One is condemned to false infinity. That is hell itself.

Evil is licence and that is why it is monotonous: everything has to be drawn from ourselves. But it is not given to man to create, so it is a bad attempt to imitate God.

Not to recognize and accept this impossibility of creating is the source of many an error. We are obliged to imitate the act of creation, and there are two possible imitations—the one real and the other apparent—preserving and destroying.

There is no trace of ‘I’ in the act of preserving. There is in that of destroying. The ‘I’ leaves its mark on the world as it destroys.

Literature and morality. Imaginary evil is romantic and varied; real evil is gloomy, monotonous, barren, boring. Imaginary good is boring; real good is always new, marvellous, intoxicating. Therefore ‘imaginative literature’ is either boring or immoral (or a mixture of both). It only escapes from this alternative if in some way it passes over to the side of reality through the power of art—and only genius can do that.

A certain inferior kind of virtue is good’s degraded image, of which we have to repent, and of which it is more difficult to repent than it is of evil—The Pharisee and the Publican.

Good as the opposite of evil is, in a sense, equivalent to it, as is the way with all opposites.

It is not good which evil violates, for good is inviolate: only a degraded good can be violated.

That which is the direct opposite of an evil never belongs to the order of higher good. It is often scarcely any higher than evil! Examples: theft and the bourgeois respect for property, adultery and the ‘respectable woman’; the savings-bank and waste; lying and ‘sincerity’.

Good is essentially other than evil. Evil is multifarious and fragmentary, good is one, evil is apparent, good is mysterious; evil consists in action, good in non-action, in activity which does not act, etc.—Good considered on the level of evil and measured against it as one opposite against another is good of the penal code order. Above there is a good which, in a sense, bears more resemblance to evil than to this low form of good. This fact opens the way to a great deal of demagogy and many tedious paradoxes.

Good which is defined in the way in which one defines evil should be rejected. Evil does reject it. But the way it rejects it is evil.

Is there a union of incompatible vices in beings given over to evil? I do not think so. Vices are subject to gravity and that is why there is no depth or transcendence in evil.

We experience good only by doing it.

We experience evil only by refusing to allow ourselves to do it, or, if we do it, by repenting of it. When we do evil we do not know it, because evil flies from the light.

Does evil, as we conceive it to be when we do not do it, exist? Does not the evil that we do seem to be something simple and natural which compels us? Is not evil analogous to illusion? When we are the victims of an illusion we do not feel it to be an illusion but a reality. It is the same perhaps with evil. Evil when we are in its power is not felt as evil but as a necessity, or even a duty.

As soon as we do evil, the evil appears as a sort of duty. Most people have a sense of duty about doing certain things that are bad and others that are good. The same man feels it to be a duty to sell for the highest price he can and not to steal etc. Good for such people is on the level of evil, it is a good without light.

The sensitivity of the innocent victim who suffers is like felt crime. True crime cannot be felt. The innocent victim who suffers knows the truth about his executioner, the executioner does not know it. The evil which the innocent victim feels in himself is in his executioner, but he is not sensible of the fact. The innocent victim can only know the evil in the form of suffering. That which is not felt by the criminal is his own crime. That which is not felt by the innocent victim is his own innocence. It is the innocent victim who can feel hell.

The sin which we have in us emerges from us and spreads outside ourselves setting up a contagion of sin. Thus, when we are in a temper, those around us grow angry. Or again, from superior to inferior: anger produces fear. But at the contact of a perfectly pure being there is a transmutation and the sin becomes suffering. Such is the function of the just servant of Isaiah, of the Lamb of God. Such is redemptive suffering. All the criminal violence of the Roman Empire ran up against Christ and in him it became pure suffering. Evil beings, on the other hand, transform simple suffering (sickness for example) into sin.

It follows, perhaps, that redemptive suffering has to have a social origin. It has to be injustice, violence on the part of human beings.

The false God changes suffering into violence. The true God changes violence into suffering.

Expiatory suffering is the shock in return for the evil we have done. Redemptive suffering is the shadow of the pure good we desire.

A hurtful act is the transference to others of the degradation which we bear in ourselves. That is why we are inclined to commit such acts as a way of deliverance.

All crime is a transference of the evil in him who acts to him who undergoes the result of the action. This is true of unlawful love as well as murder.

The apparatus of penal justice has been so contaminated with evil, after all the centuries during which it has, without any compensatory purification, been in contact with evil-doers, that a condemnation is very often a transference of evil from the penal apparatus itself to the condemned man; and that is possible even when he is guilty and the punishment is not out of proportion. Hardened criminals are the only people to whom the penal apparatus can do no harm. It does terrible harm to the innocent.

When there is a transference of evil, the evil is not diminished but increased in him from whom it proceeds. This is a phenomenon of multiplication. The same is true when the evil is transferred to things.

Where, then, are we to put the evil?

We have to transfer it from the impure part to the pure part of ourselves, thus changing it into pure suffering. The crime which is latent in us we must inflict on ourselves.

In this way, however, it would not take us long to sully our own point of inward purity if we did not renew it by contact with an unchangeable purity placed beyond all possible attack.

Patience consists in not transforming suffering into crime. That in itself is enough to transform crime into suffering.

To transfer evil to what is exterior is to distort the relationship between things. That which is exact and fixed, number, proportion, harmony, withstands this distortion. Whatever my state, whether vigorous or exhausted, in three miles there are three milestones. That is why number hurts when we are suffering: it interferes with the operation of transference. To fix my attention on what is too rigid to be distorted by my interior modifications is to prepare to make possible within myself the apparition of something changeless and an access to the eternal.

We must accept the evil done to us as a remedy for that which we have done. It is not the suffering we inflict on ourselves but that which comes to us from outside which is the true remedy. Moreover, it has to be unjust. When we have sinned by injustice it is not enough to suffer what is just, we have to suffer injustice.

Purity is absolutely invulnerable as purity, in the sense that no violence can make it less pure. It is, however, highly vulnerable in the sense that every attack of evil makes it suffer, that every sin which touches it turns in it to suffering.

If someone does me an injury I must desire that this injury shall not degrade me. I must desire this out of love for him who inflicts it, in order that he may not really have done evil.

The saints (those who are nearly saints) are more exposed than others to the devil because the real knowledge they have of their wretchedness makes the light almost intolerable.

The sin against the Spirit consists of knowing a thing to be good and hating it because it is good. We experience the equivalent of it in the form of resistance every time we set our faces in the direction of good. For every contact with good leads to a knowledge of the distance between good and evil and the commencement of a painful effort of assimilation. It is something which hurts and we are afraid. This fear is perhaps the sign of the reality of the contact. The corresponding sin cannot come about unless a lack of hope makes the consciousness of the distance intolerable and changes the pain into hatred. Hope is a remedy in this respect, but a better remedy is indifference to ourselves and happiness because the good is good although we are far from it and may even suppose that we are destined to remain separated from it for ever.

Once an atom of pure good has entered the soul the most criminal weakness is infinitely less dangerous than the very slightest treason, even though this should be confined to a purely inward movement of thought lasting no more than an instant but to which we have given our consent. That is a participation in hell. So long as the soul has not tasted of pure goodness it is separated from hell as it is from paradise.

It is only possible to choose hell through an attachment to salvation. He who does not desire the joy of God but is satisfied to know that there really is joy in God, falls but does not commit treason.

When we love God through evil as such, it is really God whom we love.

We have to love God through evil as such: to love God through the evil we hate, while hating this evil: to love God as the author of the evil which we are actually hating.

Evil is to love, what mystery is to the intelligence. As mystery compels the virtue of faith to be supernatural, so does evil the virtue of charity. Moreover, to try to find compensation or justification for evil is just as harmful for charity as to try to expose the content of the mysteries on the plane of human intelligence.

Speech of Ivan in the Karamazovs: ‘Even though this immense factory were to produce the most extraordinary marvels and were to cost only a single tear from a single child, I refuse.’

I am in complete agreement with this sentiment. No reason whatever which anyone could produce to compensate for a child’s tear would make me consent to that tear. Absolutely none which the mind can conceive. There is just one, however, but it is intelligible only to supernatural love: ‘God willed it’. And for that reason I would consent to a world which was nothing but evil as readily as to a child’s tear.

The death agony is the supreme dark night which is necessary even for the perfect if they are to attain to absolute purity, and for that reason it is better that it should be bitter.

The unreality which takes the goodness from good; this is what constitutes evil. Evil is always the destruction of tangible things in which there is the real presence of good. Evil is carried out by those who have no knowledge of this real presence. In that sense it is true that no one is wicked voluntarily. The relations between forces give to absence the power to destroy presence.

We cannot contemplate without terror the extent of the evil which man can do and endure. How could we believe it possible to find a compensation for this evil, since because of it God suffered crucifixion?

Good and evil. Reality. That which gives more reality to beings and things is good, that which takes it from them is evil. The Romans did evil by robbing the Greek towns of their statues, because the towns, the temples and the life of the Greeks had less reality without the statues, and because the statues could not have as much reality in Rome as in Greece.

The desperate, humble supplication of the Greeks to be allowed to keep some of their statues—a desperate attempt to make their own notion of value pass into the minds of others. Understood this, there is nothing base in their behaviour. But it was almost bound to be ineffectual. There is a duty to understand and weigh the system of other people’s values with our own, on the same balance—to forge the balance.

To allow the imagination to dwell on what is evil implies a certain cowardice; we hope to enjoy, to know and to grow through what is unreal.

Even to dwell in imagination on certain things as possible (quite a different thing from clearly conceiving the possibility of them, which is essential to virtue) is to commit ourselves to them already. Curiosity is the cause of it. We have to forbid ourselves certain things (not the conception of them but the dwelling on them): we must not think about them. We believe that thought does not commit us in any way, but it alone commits us, and licence of thought includes all licence. Not to think about a thing—supreme faculty. Purity—negative virtue. If we have allowed our imagination to dwell on an evil thing, if we meet other men who make it objective through their words and actions and thus remove the social barrier, we are already nearly lost. And what is easier? There is no sharp division. When we see the ditch we are already over it. With good it is quite otherwise; the ditch is visible when it has still to be crossed, at the moment of the wrench and the rending. One does not fall into good. The word baseness (lowness) expresses this property of evil.

Even when it is an accomplished fact evil keeps the character of unreality; this perhaps explains the simplicity of criminals; everything is simple in dreams. This simplicity corresponds to that of the highest virtue.

Evil has to be purified—or life is not possible. God alone can do that. This is the idea of the Gita. It is also the idea of Moses, of Mahomet, of Hitlerism… But Jehovah, Allah, Hitler are earthly Gods. The purification they bring about is imaginary.

That which is essentially different from evil is virtue accompanied by a dear perception of the possibility of evil and of evil appearing as something good. The presence of illusions which we have abandoned but which are still present in the mind is perhaps the criterion of truth.

We cannot have a horror of doing harm to others unless we have reached a point where others can no longer do harm to us (then we love others, to the furthest limit, like our past selves).

The contemplation of human misery wrenches us in the direction of God, and it is only in others whom we love as ourselves that we can contemplate it. We can neither contemplate it in ourselves as such nor in others as such.

The extreme affliction which overtakes human beings does not create human misery, it merely reveals it. Sin and the glamour of force. Because the soul in its entirety has not been able to know and accept human misery, we think that there is a difference between human beings, and in this way we fall short of justice, either by making a difference between ourselves and others or by making a selection among others.

This is because we do not know that human misery is a constant and irreducible quantity which is as great as it can be in each man, and that greatness comes from the one and only God, so that there is identity between one man and another in this respect.

We are surprised that affliction does not have an ennobling effect. This is because when we think of the afflicted person it is the affliction we have in mind. Whereas he himself does not think of his affliction: he has his soul filled with no matter what paltry comfort he may have set his heart on.

How could there be no evil in the world? The world has to be foreign to our desires. If this were so without it containing evil, our desires would then be entirely bad. That must not happen.

There is every degree of distance between the creature and God. A distance where the love of God is impossible. Matter, plants, animals. Here, evil is so complete that it destroys itself: there is no longer any evil: mirror of divine innocence. We are at the point where love is just possible. It is a great privilege, since the love which unites is in proportion to the distance.

God has created a world which is not the best possible, but which contains the whole range of good and evil. We are at the point where it is as bad as possible; for beyond is the stage where evil becomes innocence.

__

Excerpted from Simone Weil‘s Gravity and Grace. First French edition 1947. Translated by Emma Crawford. English language edition 1963. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London.