A-side of a 12″ produced by Ted Milton and Steve Beresford, and released on Embryo Records.

A-side of a 12″ produced by Ted Milton and Steve Beresford, and released on Embryo Records.

The fury of Nina Simone, recorded live at the Montreal International Jazz Festival on 2 July 1992.

I’m sure I’ve posted this on Fleurmach before, but here it is again, because it’s just so great. A version of the Weill/Brecht composition, “Seeräuberjenny” from Threepenny Opera, released on the excellent compilation Sons of Rogues’ Gallery: Pirate Ballads, Sea Songs and Shanties.

Off Last Year’s Savage. I love this video, which, according to Shilpa Ray, is a commentary on the conservative reproductive rights lobby, inspired by the Todd Akin controversy.

Here comes that ticker tape parade

Bless all my lucky stars

Cause I’ve saved the day

There goes my ego exploding

In mushroom clouds all over

My third world body

Well this air’s better

And I’m wetter

And taste just like ice cream

Don’t ever wake me up, bitch

Don’t ever wake me up

From where the gifts are pouring

The fans adoring

All the trophies that I win

I am the King

I am the King

Pretty soon I’m gonna have to let it go

Pretty soon I’m gonna have to let it go

In my fifteen hours of sleep

There’s no more suffering me

Maybe some suffering for you

This is my regime

And it’s perpetual pageantry

There’s no existence of my mistakes

No humility

Well my dick’s bigger

My breasts are thicker

Whatever power means

Don’t ever wake me up, bitch

Don’t ever wake me up

From where I’m well fed

I’m well bred

Shitting 24ct bricks

I am the King

I am the King

And pretty soon I’m gonna have to let it go

And pretty soon I’m gonna have to let it go

Pretty soon I’m gonna have to let it go

In my 15 hours of sleep

Here comes that ticker tape parade

And there goes my ego exploding

Here comes that ticker tape parade

There goes my ego exploding

Here comes that ticker tape parade

There goes my ego exploding

A koeksuster twist.

Nina Hagen’s mother singing the hell out of this Hauptmann/Brecht/Weill song from the musical Happy End.

Here’s a (totally different) version by Nina, too:

Tychbornes Elegie, written with his owne hand in the Tower before his execution*

My prime of youth is but a frost of cares,

My prime of youth is but a frost of cares,

My feast of joy is but a dish of paine,

My Crop of corne is but a field of tares,

And al my good is but vaine hope of gaine.

The day is past, and yet I saw no sunne,

And now I live, and now my life is done.

My tale was heard, and yet it was not told,

My fruite is falne, & yet my leaves are greene:

My youth is spent, and yet I am not old,

I saw the world, and yet I was not seene.

My thred is cut, and yet it is not spunne,

And now I live, and now my life is done.

I sought my death, and found it in my wombe,

I lookt for life, and saw it was a shade:

I trod the earth, and knew it was my Tombe,

And now I die, and now I was but made.

My glasse is full, and now my glasse is runne,

And now I live, and now my life is done.

__

*Chidiock Tichborne was one of fourteen convicted in 1586 in the plot to kill Queen Elizabeth 1 of England.

Recorded at the New York Public Library on October 27, 2010.

Pick an old photograph of you. Go back and look what was happening in the world around the time it was taken.

1 September 1984

It was a Saturday. The US president was Ronald Reagan. The UK Prime Minister was Margaret Thatcher. In that week of September people in US were listening to “What’s Love Got To Do With It” by Tina Turner. In the UK “Careless Whisper” by George Michael was in the top 5 hits. Amadeus, directed by Milos Forman, was one of the most viewed movies released in 1984 while First Among Equals by Jeffrey Archer was one of the best selling books. (From HERE).

In South Africa, on 3 September 1984, the day the new constitution creating the tri-cameral parliament became effective, and the day upon which the first executive state president took the oath of office, the Vaal exploded and unrest and rioting spread countrywide. Read more HERE.

From SA History Online:

1984

12 July, A car bomb explosion in Durban, Natal, kills five and injures twenty-six.

13 July, The last all white Parliament ends its last session in Cape Town.

16 July, Supreme Court Act No 2: Provided for the separation of the Ciskei judiciary from South Africa. Commenced: 16 July 1984

27 July, Republic of Ciskei Constitution Amendment Act No 10: Removed the post of VicePresident. Commenced: 27 July 1984

30 July, Campaigning for the new tricameral Parliament begins.

30 July, South Africa has held up supplies of British weapons to Lesotho and the UK has complained several times about the delays, officials said today. South Africa has decided to close its Consulate in Wellington instead of waiting for New Zealand’s new Government to carry out its pledge to shut down, New Zealand’s Prime Minister David Lange said.

August, Elections for Coloured and Indian Chambers of Parliament.

August, Boycotts and demonstrations in schools affected about 7% of the school population. In August demonstrations affected 800 000 school children.

7 August-9 August, Conference of Arab Solidarity with the Struggle for Liberation in Southern Africa, organised by the Special Committee against Apartheid, in cooperation with the League of Arab States.

8 August, The government is to grant self government to KaNgwane. This is seen as confirmation that it has finally abandoned its land deal with Swaziland, of which KaNgwane was to have been a part.

14 August, Lesotho rejects South Africa’s proposal for a draft security treaty.

16 August, An explosion, believed to have been caused by a bomb, ripped through police offices near Johannesburg today, a police spokesman said.

17 August, The UN Security Council rejected and declared null and void the new racist constitution of South Africa. It urged governments and organisations not to accord recognition to the “elections“ under that constitution. (Resolution 554)

22 August, Elections to the House of Representatives among the Coloured community show overwhelming support for the Labour Party. Official results record only a 30.9 per cent turn out and protests and boycotts are followed by 152 arrests.

28 August, Elections to the House of Delegates among the Indian community are marked by a low poll, protests, boycotts and active opposition by the UDF. Results show eighteen seats for the National Peoples Party (NPP), seventeen for Solidarity, one for the Progressive Independent Party (PIP), four for independents.

30 August, Prime Minister Botha declares that the government does not see the low turnout at the poils as invalidating the revised constitution.

31 August, KaNgwane proclaimed a self governing territory.

31 August, South Africa declared the black homeland of KaNgwane on the Swaziland border a self governing territory. The Swazi Council of Chiefs of South Africa, which backs a controversial plan to incorporate KaNgwane into Swaziland, warned of possible bloodshed in the territory if it is granted independence.

September, Mr P.W. Botha was elected the first executive state president in September. 1984-1986.

September – 24 January 1986, From 1 September 1984 to 24 January 1986, 955 people were killed in political violence incidents, 3 658 injured. 25 members of the security forces were killed and 834 injured. There were 3 400 incidents of violence in the Western Cape.

2 September-3 September, The revised Constitution comes into effect.

3 September, As South Africa’s new Constitution was inaugurated at least 26 people died in riots and police counterattacks in black townships, according to press and news agency reports. Reuter reported that the military has been brought in to guard Government buildings in Sharpeville and other black townships.

3 September, 175 people were killed in political violence incidents. On September 3 violence erupted in the Vaal Triangle, within a few days 31 people were killed.

5 September, P.W. Botha is unanimously elected to the post of Executive President by an Electoral College composed of the majority parties in each house fifty NP members of the white House of Assembly, twentyfive Labour Party members of the Coloured House of Representatives, and thirteen National People’s Party members of the Indian House of Delegates.

10 September, Fresh detention orders were issued for seven opponents of the South African Government freed by a court on Friday. The seven, including Archie Gumede, President of the two million strong anti apartheid United Democratic Front, had been held without charge since just before the controversial elections to a new Parliament in August.

11 September, Following unrest and rioting in the townships, the Minister of Law and Order prohibits all meetings of more than two persons, discussing politics or which is in protest against or in support or in memorium of anything, until 30 September 1984. The ban extends to certain areas in all four provinces, but is most comprehensive in the Transvaal.

12 September, South African riot police used tear gas and whips in Soweto as unrest continued and a sweeping ban on meetings critical of the Government came into effect. Opposition leaders criticised the ban, saying that the Government appeared to be overreacting to the unrest, in which about 40 people had died in the past fortnight.

13 September, Six political refugees, including the President of the United Democratic Front (UDF) seek refuge in the British consulate in Durban, and ask the British government to intervene on their behalf.

13 September, Six South African dissidents hunted by police in a big security clampdown today entered the British Consulate in Durban, British officials said. Police had been trying to rearrest the six, leaders of the United Democratic Front and the natal Indian Congress, following their release from detention last Friday on the orders of a judge. Major military manoeuvres were conducted by the South African Defence Force in its biggest exercise since World War II, which, the Times contends in a separate article, will surely be interpreted by the neighbouring States as a show of hostile preparedness. The exercise seemed to illustrate the successes and the failures of South Africa’s efforts to circumvent the international arms embargo imposed in 1977, the paper adds, noting that Western military specialists were impressed by the manoeuvres.

14 September, The inauguration of the new President, P.W. Botha, takes place. Under the revised Constitution, the post of President combines the ceremonial duties of Head of State with the executive functions of Prime Minister. Mr. Botha is also chairman of the Cabinet, Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces and controls the National Intelligence Service which includes the Secretariat of the State Security Council.

Margaret Thatcher, the British Prime Minister, gives an assurance that the six refugees will not be required to leave the consulate against their will, but also states that Britain will not become involved in negotiations between the fugitives and the South African government.

15 September, Members of a new Cabinet responsible for general affairs of government and three Ministers’ Councils are appointed and sworn in on 17 September 1984.

The leader of the Labour Party, the Reverend H.J. (Allan) Hendrikse and A. Rajbansi of the NPP are appointed to the Cabinet as Chairmen of the Ministers’ Councils, but neither is given a ministerial portfolio.

17 September, Over the weekend, South Africa’s new President, Pieter W. Botha, announced the appointment of a Cabinet which, for the first time in South Africa’s history, includes non-whites.

The two non-white Cabinet members, the Reverend Allan Hendrickse, leader of the Labour Party, and Amichand Rajbansi, whose National People’s Party is drawn from the Indian community, were sworn into office in Cape Town, along with the other members of the new 19 man Cabinet for General Affairs, which is otherwise all white.

18 September, South Africa’s black gold miners today called off their first legal strike, which lasted just one day but, according to mine owners, saw 250 workers injured during police action against pickets.

19 September, Riot police firing birdshot, tear gas and rubber bullets clashed with 8,000 striking gold miners, killing seven and injuring 89, police said today.

24 September, Minister of Foreign Affairs, ‘Pik’ Botha, announces that in retaliation for the British government’s refusal to give up the six men, the government will not return to Britain four South Africans due to face charges of having contravened British customs and excise regulations, and believed to be employed by ARMSCOR.

25 September, South Africa and the UK faced what could be their worst diplomatic crisis for several years because of tension over six dissidents hiding from police in the British Consulate in Durban. Pretoria said last night that in retaliation for London’s refusal to evict the fugitives it would not send four South African back to Britain to stand trial on charges of illegal export of arms.

26 September, Five of the political detainees are released and on the same day the banning order on Dr. Beyers Naudé is lifted.

Schools reopen, but 93,000 pupils continue to boycott classes.

28 September, South Africa was told by IAEA to open all nuclear plants to international inspection or face sanctions by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The resolution was passed by 57 votes to 10, with 23 abstentions. The US and other Western nations opposed it. The resolution was tabled by Morocco on behalf of African States.

2 October, The death toll in rioting and clashes with police has risen to over sixty.

2 October, The Government took into custody the leader of South Africa’s most prominent anti-apartheid group and held him under security law. The arrest came as four blacks were killed in a day of unrest in black townships raising to at least 61 the number of people killed in the past month in ethnic violence and 130,000 black students boycotted classes.

“The crisis facing men is not the crisis of masculinity, it is the crisis of patriarchal masculinity. Until we make this distinction clear, men will continue to fear that any critique of patriarchy represents a threat.”

Patriarchy is the single most life-threatening social disease assaulting the male body and spirit in our nation. Yet most men do not use the word “patriarchy” in everyday life. Most men never think about patriarchy—what it means, how it is created and sustained. Many men in our nation would not be able to spell the word or pronounce it correctly. The word “patriarchy” just is not a part of their normal everyday thought or speech.

Men who have heard and know the word usually associate it with women’s liberation, with feminism, and therefore dismiss it as irrelevant to their own experiences. I have been standing at podiums talking about patriarchy for more than thirty years. It is a word I use daily, and men who hear me use it often ask me what I mean by it.

Nothing discounts the old antifeminist projection of men as all-powerful more than their basic ignorance of a major facet of the political system that shapes and informs male identity and sense of self from birth until death. I often use the phrase “imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy” to describe the interlocking political systems that are the foundation of our nation’s politics. Of these systems the one that we all learn the most about growing up is the system of patriarchy, even if we never know the word, because patriarchal gender roles are assigned to us as children and we are given continual guidance about the ways we can best fulfill these roles.

Patriarchy is a political-social system that insists that males are inherently dominating, superior to everything and everyone deemed weak, especially females, and endowed with the right to dominate and rule over the weak and to maintain that dominance through various forms of psychological terrorism and violence. When my older brother and I were born with a year separating us in age, patriarchy determined how we would each be regarded by our parents. Both our parents believed in patriarchy; they had been taught patriarchal thinking through religion.

At church they had learned that God created man to rule the world and everything in it and that it was the work of women to help men perform these tasks, to obey, and to always assume a subordinate role in relation to a powerful man. They were taught that God was male. These teachings were reinforced in every institution they encountered– schools, courthouses, clubs, sports arenas, as well as churches. Embracing patriarchal thinking, like everyone else around them, they taught it to their children because it seemed like a “natural” way to organize life.

As their daughter I was taught that it was my role to serve, to be weak, to be free from the burden of thinking, to caretake and nurture others. My brother was taught that it was his role to be served; to provide; to be strong; to think, strategize, and plan; and to refuse to caretake or nurture others. I was taught that it was not proper for a female to be violent, that it was “unnatural.” My brother was taught that his value would be determined by his will to do violence (albeit in appropriate settings). He was taught that for a boy, enjoying violence was a good thing (albeit in appropriate settings). He was taught that a boy should not express feelings. I was taught that girls could and should express feelings, or at least some of them.

When I responded with rage at being denied a toy, I was taught as a girl in a patriarchal household that rage was not an appropriate feminine feeling, that it should not only not be expressed but be eradicated. When my brother responded with rage at being denied a toy, he was taught as a boy in a patriarchal household that his ability to express rage was good but that he had to learn the best setting to unleash his hostility. It was not good for him to use his rage to oppose the wishes of his parents, but later, when he grew up, he was taught that rage was permitted and that allowing rage to provoke him to violence would help him protect home and nation.

We lived in farm country, isolated from other people. Our sense of gender roles was learned from our parents, from the ways we saw them behave. My brother and I remember our confusion about gender. In reality I was stronger and more violent than my brother, which we learned quickly was bad. And he was a gentle, peaceful boy, which we learned was really bad. Although we were often confused, we knew one fact for certain: we could not be and act the way we wanted to, doing what we felt like. It was clear to us that our behavior had to follow a predetermined, gendered script. We both learned the word “patriarchy” in our adult life, when we learned that the script that had determined what we should be, the identities we should make, was based on patriarchal values and beliefs about gender.

I was always more interested in challenging patriarchy than my brother was because it was the system that was always leaving me out of things that I wanted to be part of. In our family life of the fifties, marbles were a boy’s game. My brother had inherited his marbles from men in the family; he had a tin box to keep them in. All sizes and shapes, marvelously colored, they were to my eye the most beautiful objects. We played together with them, often with me aggressively clinging to the marble I liked best, refusing to share. When Dad was at work, our stay-at-home mom was quite content to see us playing marbles together. Yet Dad, looking at our play from a patriarchal perspective, was disturbed by what he saw. His daughter, aggressive and competitive, was a better player than his son. His son was passive; the boy did not really seem to care who won and was willing to give over marbles on demand. Dad decided that this play had to end, that both my brother and I needed to learn a lesson about appropriate gender roles.

One evening my brother was given permission by Dad to bring out the tin of marbles. I announced my desire to play and was told by my brother that “girls did not play with marbles,” that it was a boy’s game. This made no sense to my four- or five-year-old mind, and I insisted on my right to play by picking up marbles and shooting them. Dad intervened to tell me to stop. I did not listen. His voice grew louder and louder. Then suddenly he snatched me up, broke a board from our screen door, and began to beat me with it, telling me, “You’re just a little girl. When I tell you to do something, I mean for you to do it.” He beat me and he beat me, wanting me to acknowledge that I understood what I had done. His rage, his violence captured everyone’s attention. Our family sat spellbound, rapt before the pornography of patriarchal violence.

After this beating I was banished—forced to stay alone in the dark. Mama came into the bedroom to soothe the pain, telling me in her soft southern voice, “I tried to warn you. You need to accept that you are just a little girl and girls can’t do what boys do.” In service to patriarchy her task was to reinforce that Dad had done the right thing by, putting me in my place, by restoring the natural social order.

I remember this traumatic event so well because it was a story told again and again within our family. No one cared that the constant retelling might trigger post-traumatic stress; the retelling was necessary to reinforce both the message and the remembered state of absolute powerlessness. The recollection of this brutal whipping of a little-girl daughter by a big strong man, served as more than just a reminder to me of my gendered place, it was a reminder to everyone watching/remembering, to all my siblings, male and female, and to our grown-woman mother that our patriarchal father was the ruler in our household. We were to remember that if we did not obey his rules, we would be punished, punished even unto death. This is the way we were experientially schooled in the art of patriarchy.

There is nothing unique or even exceptional about this experience. Listen to the voices of wounded grown children raised in patriarchal homes and you will hear different versions with the same underlying theme, the use of violence to reinforce our indoctrination and acceptance of patriarchy. In How Can I Get Through to You? family therapist Terrence Real tells how his sons were initiated into patriarchal thinking even as their parents worked to create a loving home in which antipatriarchal values prevailed. He tells of how his young son Alexander enjoyed dressing as Barbie until boys playing with his older brother witnessed his Barbie persona and let him know by their gaze and their shocked, disapproving silence that his behavior was unacceptable:

Without a shred of malevolence, the stare my son received transmitted a message. You are not to do this. And the medium that message was broadcast in was a potent emotion: shame. At three, Alexander was learning the rules. A ten second wordless transaction was powerful enough to dissuade my son from that instant forward from what had been a favorite activity. I call such moments of induction the “normal traumatization” of boys.

To indoctrinate boys into the rules of patriarchy, we force them to feel pain and to deny their feelings.

My stories took place in the fifties; the stories Real tells are recent. They all underscore the tyranny of patriarchal thinking, the power of patriarchal culture to hold us captive. Real is one of the most enlightened thinkers on the subject of patriarchal masculinity in our nation, and yet he lets readers know that he is not able to keep his boys out of patriarchy’s reach. They suffer its assaults, as do all boys and girls, to a greater or lesser degree. No doubt by creating a loving home that is not patriarchal, Real at least offers his boys a choice: they can choose to be themselves or they can choose conformity with patriarchal roles. Real uses the phrase “psychological patriarchy” to describe the patriarchal thinking common to females and males. Despite the contemporary visionary feminist thinking that makes clear that a patriarchal thinker need not be a male, most folks continue to see men as the problem of patriarchy. This is simply not the case. Women can be as wedded to patriarchal thinking and action as men.

Psychotherapist John Bradshaw’s clear sighted definition of patriarchy in Creating Love is a useful one: “The dictionary defines ‘patriarchy’ as a ‘social organization marked by the supremacy of the father in the clan or family in both domestic and religious functions’.” Patriarchy is characterized by male domination and power. He states further that “patriarchal rules still govern most of the world’s religious, school systems, and family systems.” Describing the most damaging of these rules, Bradshaw lists “blind obedience—the foundation upon which patriarchy stands; the repression of all emotions except fear; the destruction of individual willpower; and the repression of thinking whenever it departs from the authority figure’s way of thinking.” Patriarchal thinking shapes the values of our culture. We are socialized into this system, females as well as males. Most of us learned patriarchal attitudes in our family of origin, and they were usually taught to us by our mothers. These attitudes were reinforced in schools and religious institutions.

The contemporary presence of female-headed households has led many people to assume that children in these households are not learning patriarchal values because no male is present. They assume that men are the sole teachers of patriarchal thinking. Yet many female-headed households endorse and promote patriarchal thinking with far greater passion than two-parent households. Because they do not have an experiential reality to challenge false fantasies of gender roles, women in such households are far more likely to idealize the patriarchal male role and patriarchal men than are women who live with patriarchal men every day. We need to highlight the role women play in perpetuating and sustaining patriarchal culture so that we will recognize patriarchy as a system women and men support equally, even if men receive more rewards from that system. Dismantling and changing patriarchal culture is work that men and women must do together.

Clearly we cannot dismantle a system as long as we engage in collective denial about its impact on our lives. Patriarchy requires male dominance by any means necessary, hence it supports, promotes, and condones sexist violence. We hear the most about sexist violence in public discourses about rape and abuse by domestic partners. But the most common forms of patriarchal violence are those that take place in the home between patriarchal parents and children. The point of such violence is usually to reinforce a dominator model, in which the authority figure is deemed ruler over those without power and given the right to maintain that rule through practices of subjugation, subordination, and submission.

Keeping males and females from telling the truth about what happens to them in families is one way patriarchal culture is maintained. A great majority of individuals enforce an unspoken rule in the culture as a whole that demands we keep the secrets of patriarchy, thereby protecting the rule of the father. This rule of silence is upheld when the culture refuses everyone easy access even to the word “patriarchy.” Most children do not learn what to call this system of institutionalized gender roles, so rarely do we name it in everyday speech. This silence promotes denial. And how can we organize to challenge and change a system that cannot be named?

It is no accident that feminists began to use the word “patriarchy” to replace the more commonly used “male chauvinism” and “sexism.” These courageous voices wanted men and women to become more aware of the way patriarchy affects us all. In popular culture the word itself was hardly used during the heyday of contemporary feminism. Antimale activists were no more eager than their sexist male counterparts to emphasize the system of patriarchy and the way it works. For to do so would have automatically exposed the notion that men were all-powerful and women powerless, that all men were oppressive and women always and only victims. By placing the blame for the perpetuation of sexism solely on men, these women could maintain their own allegiance to patriarchy, their own lust for power. They masked their longing to be dominators by taking on the mantle of victimhood.

Like many visionary radical feminists I challenged the misguided notion, put forward by women who were simply fed up with male exploitation and oppression, that men were “the enemy.” As early as 1984 I included a chapter with the title “Men: Comrades in Struggle” in my book Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center urging advocates of feminist politics to challenge any rhetoric which placed the sole blame for perpetuating patriarchy and male domination onto men:

Separatist ideology encourages women to ignore the negative impact of sexism on male personhood. It stresses polarization between the sexes. According to Joy Justice, separatists believe that there are “two basic perspectives” on the issue of naming the victims of sexism: “There is the perspective that men oppress women. And there is the perspective that people are people, and we are all hurt by rigid sex roles.”…Both perspectives accurately describe our predicament. Men do oppress women. People are hurt by rigid sexist role patterns, These two realities coexist. Male oppression of women cannot be excused by the recognition that there are ways men are hurt by rigid sexist roles. Feminist activists should acknowledge that hurt, and work to change it—it exists. It does not erase or lessen male responsibility for supporting and perpetuating their power under patriarchy to exploit and oppress women in a manner far more grievous than the serious psychological stress and emotional pain caused by male conformity to rigid sexist role patterns.

Throughout this essay I stressed that feminist advocates collude in the pain of men wounded by patriarchy when they falsely represent men as always and only powerful, as always and only gaining privileges from their blind obedience to patriarchy. I emphasized that patriarchal ideology brainwashes men to believe that their domination of women is beneficial when it is not:

Often feminist activists affirm this logic when we should be constantly naming these acts as expressions of perverted power relations, general lack of control of one’s actions, emotional powerlessness, extreme irrationality, and in many cases, outright insanity. Passive male absorption of sexist ideology enables men to falsely interpret this disturbed behavior positively. As long as men are brainwashed to equate violent domination and abuse of women with privilege, they will have no understanding of the damage done to themselves or to others, and no motivation to change.

Patriarchy demands of men that they become and remain emotional cripples. Since it is a system that denies men full access to their freedom of will, it is difficult for any man of any class to rebel against patriarchy, to be disloyal to the patriarchal parent, be that parent female or male.

The man who has been my primary bond for more than twelve years was traumatized by the patriarchal dynamics in his family of origin. When I met him he was in his twenties. While his formative years had been spent in the company of a violent, alcoholic dad, his circumstances changed when he was twelve and he began to live alone with his mother.

In the early years of our relationship he talked openly about his hostility and rage toward his abusing dad. He was not interested in forgiving him or understanding the circumstances that had shaped and influenced his dad’s life, either in his childhood or in his working life as a military man. In the early years of our relationship he was extremely critical of male domination of women and children. Although he did not use the word “patriarchy,” he understood its meaning and he opposed it. His gentle, quiet manner often led folks to ignore him, counting him among the weak and the powerless. By the age of thirty he began to assume a more macho persona, embracing the dominator model that he had once critiqued. Donning the mantle of patriarch, he gained greater respect and visibility. More women were drawn to him. He was noticed more in public spheres. His criticism of male domination ceased. And indeed he begin to mouth patriarchal rhetoric, saying the kind of sexist stuff that would have appalled him in the past.

These changes in his thinking and behavior were triggered by his desire to be accepted and affirmed in a patriarchal workplace and rationalized by his desire to get ahead. His story is not unusual. Boys brutalized and victimized by patriarchy more often than not become patriarchal, embodying the abusive patriarchal masculinity that they once clearly recognized as evil. Few men brutally abused as boys in the name of patriarchal maleness courageously resist the brainwashing and remain true to themselves. Most males conform to patriarchy in one way or another.

Indeed, radical feminist critique of patriarchy has practically been silenced in our culture. It has become a subcultural discourse available only to well-educated elites. Even in those circles, using the word “patriarchy” is regarded as passé. Often in my lectures when I use the phrase “imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy” to describe our nation’s political system, audiences laugh. No one has ever explained why accurately naming this system is funny. The laughter is itself a weapon of patriarchal terrorism. It functions as a disclaimer, discounting the significance of what is being named. It suggests that the words themselves are problematic and not the system they describe. I interpret this laughter as the audience’s way of showing discomfort with being asked to ally themselves with an anti-patriarchal disobedient critique. This laughter reminds me that if I dare to challenge patriarchy openly, I risk not being taken seriously.

Citizens in this nation fear challenging patriarchy even as they lack overt awareness that they are fearful, so deeply embedded in our collective unconscious are the rules of patriarchy. I often tell audiences that if we were to go door-to-door asking if we should end male violence against women, most people would give their unequivocal support. Then if you told them we can only stop male violence against women by ending male domination, by eradicating patriarchy, they would begin to hesitate, to change their position. Despite the many gains of contemporary feminist movement—greater equality for women in the workforce, more tolerance for the relinquishing of rigid gender roles—patriarchy as a system remains intact, and many people continue to believe that it is needed if humans are to survive as a species. This belief seems ironic, given that patriarchal methods of organizing nations, especially the insistence on violence as a means of social control, has actually led to the slaughter of millions of people on the planet.

Until we can collectively acknowledge the damage patriarchy causes and the suffering it creates, we cannot address male pain. We cannot demand for men the right to be whole, to be givers and sustainers of life. Obviously some patriarchal men are reliable and even benevolent caretakers and providers, but still they are imprisoned by a system that undermines their mental health.

Patriarchy promotes insanity. It is at the root of the psychological ills troubling men in our nation. Nevertheless there is no mass concern for the plight of men. In Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man, Susan Faludi includes very little discussion of patriarchy:

Ask feminists to diagnose men’s problems and you will often get a very clear explanation: men are in crisis because women are properly challenging male dominance. Women are asking men to share the public reins and men can’t bear it. Ask antifeminists and you will get a diagnosis that is, in one respect, similar. Men are troubled, many conservative pundits say, because women have gone far beyond their demands for equal treatment and are now trying to take power and control away from men…The underlying message: men cannot be men, only eunuchs, if they are not in control. Both the feminist and antifeminist views are rooted in a peculiarly modern American perception that to be a man means to be at the controls and at all times to feel yourself in control.

Faludi never interrogates the notion of control. She never considers that the notion that men were somehow in control, in power, and satisfied with their lives before contemporary feminist movement is false.

Patriarchy as a system has denied males access to full emotional well-being, which is not the same as feeling rewarded, successful, or powerful because of one’s capacity to assert control over others. To truly address male pain and male crisis we must as a nation be willing to expose the harsh reality that patriarchy has damaged men in the past and continues to damage them in the present. If patriarchy were truly rewarding to men, the violence and addiction in family life that is so all-pervasive would not exist. This violence was not created by feminism. If patriarchy were rewarding, the overwhelming dissatisfaction most men feel in their work lives—a dissatisfaction extensively documented in the work of Studs Terkel and echoed in Faludi’s treatise—would not exist.

In many ways Stiffed was yet another betrayal of American men because Faludi spends so much time trying not to challenge patriarchy that she fails to highlight the necessity of ending patriarchy if we are to liberate men. Rather she writes:

Instead of wondering why men resist women’s struggle for a freer and healthier life, I began to wonder why men refrain from engaging in their own struggle. Why, despite a crescendo of random tantrums, have they offered no methodical, reasoned response to their predicament: Given the untenable and insulting nature of the demands placed on men to prove themselves in our culture, why don’t men revolt?…Why haven’t men responded to the series of betrayals in their own lives—to the failures of their fathers to make good on their promises–with something coequal to feminism?

Note that Faludi does not dare risk either the ire of feminist females by suggesting that men can find salvation in feminist movement or rejection by potential male readers who are solidly antifeminist by suggesting that they have something to gain from engaging feminism. So far in our nation visionary feminist movement is the only struggle for justice that emphasizes the need to end patriarchy. No mass body of women has challenged patriarchy and neither has any group of men come together to lead the struggle. The crisis facing men is not the crisis of masculinity, it is the crisis of patriarchal masculinity. Until we make this distinction clear, men will continue to fear that any critique of patriarchy represents a threat. Distinguishing political patriarchy, which he sees as largely committed to ending sexism, therapist Terrence Real makes clear that the patriarchy damaging us all is embedded in our psyches: Psychological patriarchy is the dynamic between those qualities deemed “masculine” and “feminine” in which half of our human traits are exalted while the other half is devalued. Both men and women participate in this tortured value system.

Psychological patriarchy is a “dance of contempt,” a perverse form of connection that replaces true intimacy with complex, covert layers of dominance and submission, collusion and manipulation. It is the unacknowledged paradigm of relationships that has suffused Western civilization generation after generation, deforming both sexes, and destroying the passionate bond between them.

By highlighting psychological patriarchy, we see that everyone is implicated and we are freed from the misperception that men are the enemy. To end patriarchy we must challenge both its psychological and its concrete manifestations in daily life. There are folks who are able to critique patriarchy but unable to act in an antipatriarchal manner.

To end male pain, to respond effectively to male crisis, we have to name the problem. We have to both acknowledge that the problem is patriarchy and work to end patriarchy. Terrence Real offers this valuable insight:

“The reclamation of wholeness is a process even more fraught for men than it has been for women, more difficult and more profoundly threatening to the culture at large.”

If men are to reclaim the essential goodness of male being, if they are to regain the space of openheartedness and emotional expressiveness that is the foundation of well-being, we must envision alternatives to patriarchal masculinity. We must all change.

___

This is an excerpt from The Will To Change by bell hooks (chapter 2).

bell hooks is an American social activist, feminist and author. She was born on September 25, 1952. bell hooks is the nom de plume for Gloria Jean Watkins. bell hooks examines the multiple networks that connect gender, race, and class. She examines systematic oppression with the goal of a liberatory politics. She also writes on the topics of mass media, art, and history. bell hooks is a prolific writer, having composed a plethora of articles for mainstream and scholarly publications. bell hooks has written and published dozens of books. At Yale University, bell hooks was a Professor of African and African-American Studies and English. At Oberlin College, she was an Associate Professor of Women‚’s Studies and American Literature. At the City College of New York, bell hooks also held the position of Distinguished Lecturer of English Literature. bell hooks has been awarded The American Book Awards/Before Columbus Foundation Award, The Writer’s Award from Lila Wallace-Reader’s Digest Fund, and The Bank Street College Children’s Book of the Year. She has also been ranked as one of the most influential American thinkers by Publisher’s Weekly and The Atlantic monthly.

This work is licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

I have made a promise to this world that I will carry with me to my last days. It is my vow to lessen the suffering of the world while I am here – it is to ensure that every toxic legacy that I inherited from our culture ends with me – and, ideally, ends with all of us, in our lifetime. The task may be impossible, but I have to help. I have to do it because my true nature wants me to. When I do this work, my heart sings. My inner self rejoices. That is because your happiness is my happiness. Doing the work connects me with what is really true. We are all connected. We are all in relationship.

Focusing on media activism, it is quite easy to get swept up in a thousand different messages, leaving me sometimes feeling like I’ve gotten off track with my core message and purpose. What am I doing here? Why am I here?

The answer is in an old Sufi song I learned as a child, “What are we here for? To love, serve and remember.”

To love, serve and remember.

Remember what?

That we are all family.

That you are because I am.

That what is sacred in me is sacred in you. And that sacredness pervades the cosmos, if we choose.*

Reverence and awe for the world is our choice to make. We can see that beauty, and live that life, or we can choose not to see it, and live without that beauty.

Look at your lover this way today. See the sacred in her. See the sacred in him. When you see it in them, see it in your family and your friends. Then, start looking for it in people you see at the grocery store and on the street. Then see it in all of the animal creatures in your life. See it in the trees and plants that grow outside your house. See life in everything, truly be present to its nature and vibrational energy.

Each person in the world is family – caught with us amid the “splendour and travail of the earth.”

When we see the sacred in every person, we can see that those who cause others to suffer are also suffering and have been deeply wounded by this culture since they were born. Every child is born with love in their hearts. The child does not know that we are not all family until they are taught so. This is how we forget.

Our culture teaches us to forget. Our culture teaches us who to love and who not to love. It is a very small circle of people. But that circle is growing bigger for more and more people each day.

More and more people are remembering that our family is life itself.

That is the core message I am trying to spread with my activism.

From this revolution of the heart flowers every other revolution. Sexism, racism, environmental destruction, poverty and war are not possible when true love is there. True love dissolves illusion. True love shatters prejudice and malice. True love liberates both the child and the adult from centuries of our inherited suffering. It is the revolution we need most desperately to save every 5 year old child from the suffering they will inherit if we do not vow to ensure that every toxic cultural legacy of our culture ends with us.

*I define sacred as something having intrinsic worth and value, so for me the word connects with me on both a secular and spiritual level. In a scientific sense that value may be entirely subjective, but I’m okay with that. For me, it’s a choice to see the sacred in life. I can choose to see that beauty, or not see it.

___

Tim Hjersted is the director and co-founder of Films For Action. 16 August 2016.

This work is licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

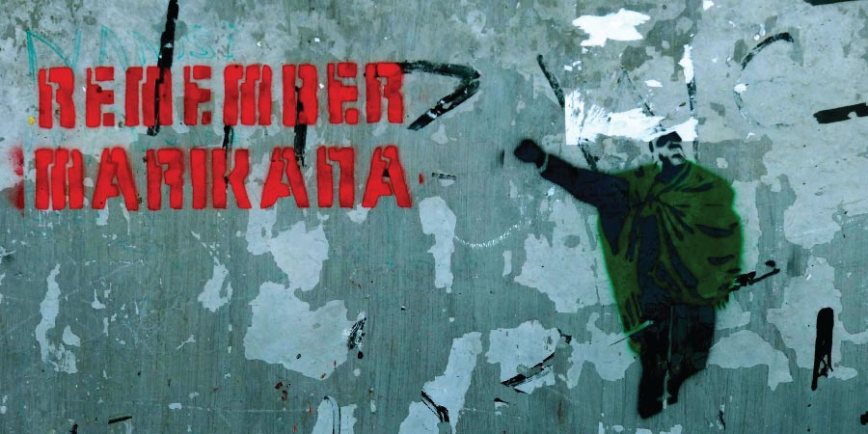

This is a research paper I wrote in 2014 for “The Public Life of the Image”, an MPhil course offered through the Centre for African Studies at the University of Cape Town.

“[T]he striking mine workers at Marikana have become spectacularised. It is a stark reminder that the mine worker, a modern subject of capitalism, in these parts of the world is also the product of a colonial encounter.”

— Suren Pillay (2014)

“We need to understand how photography works within everyday life in advanced industrial societies: the problem is one of materialist cultural history rather than art history.”

— Allan Sekula (2003)

__

I pick up the odd wood and metal contraption. This is a stereoscope, I am told. It feels old, in the sense that there is a certain worn patina about it, and a non-utilitarian elegance to the turned wood and decoration, though not as if it were an expensive piece – just as if it came from an era where there was time for embellishment. It feels cheaply put together, mass-produced and flimsy as opposed to delicate, the engraving detail of the tinny sheet metal rather rough, the fit of the one piece as it glides through the other somewhat rickety in my hands.

From two elevations, a stereoscope almost identical to the one I used. Various kinds were devised in the 19th century. The particular hand-held variety, of oak, tin, glass and velvet depicted here dates back to 1901, Based on a design by the inventor Oliver Wendell Holmes, it is perhaps the most readily available and simplest model.

I reach for the pile of faded stereographs; flipping through them slowly. There are 24, picked up in an antique shop in an arcade off Cape Town’s Long Street together with the viewing device. A stereograph is composed of two photographs of the same subject taken from slightly different angles. When placed in the stereoscope’s wire holder, and viewed through the eyeholes, an illusion of perspective and depth is achieved as the two images appear to combine through a trick of parallax.

Susan Sontag remarks that “[p]hotographs, which cannot themselves explain anything, are inexhaustible invitations to deduction, speculation, and fantasy”2. And Allan Sekula calls the photograph an “incomplete utterance, a message that depends on some external matrix of conditions and presuppositions for its readability. That is, the meaning of any photographic message is necessarily context determined”3. In what follows, while unable to offer definitive conclusions, I will look more closely at 2 out of these 24 pictures and, through a contextual discussion, attempt to unpack a few aspects of the complex relationships of photography with its subjects and also with public circulation.

Each thick, oblong card with its rounded, scuffed edges discoloured by age has two seemingly identical images on it, side by side, and is embossed with the name of what I guess must have been the photographer or printing studio’s name in gold down the margin: “RAYMOND NEILSON, BOX 145, JOHANNESBURG”. The images depict miners underground. Some are very faded, to the extent that the figures in them appear featureless and ghostly. There is virtually no annotation on most of the photos. On just a few of them, spidery white handwriting on the photo itself, as if scratched into the negative before it was printed, announces the name of the machinery or activity in the picture and the name of the mine: “Crown Mines”.

I pick up the first card, slot it into the stereoscope, and peer through the device. On the left of the two images, the writing announces: “Ingersoll hammer drill cutting box hole. C215. Crown Mines.”

I slide the holder backwards and forwards along the wooden shaft to focus. I’m seeing two images, nothing remarkable, until suddenly, at a precise point on the axis, the images coalesce into one, three-dimensional. The experience is that of a gestalt switch, the optical illusion uncanny. I blink hard. It’s still there. It feels magical, as if the figures in the photos are stepping right out of the card towards me. Their eyes stare into mine through over a century of time, gleaming white out of dirty, sweaty faces.

Startlingly tangible, here stand two young white men in a mine shaft, scarcely out of their teens, leaning against rock, each with a hand on a hip and a jauntily cocked hat. They are very young… yet very old too, I immediately think: definitely dead now; and perhaps dead soon after the picture was taken, living at risk, killed in a rock fall or in World War One. A pang of indefinable emotion hits. I am amazed at how powerfully this image has flooded my imagination. Even with the difficult viewing process, the effect is astonishing.

I am reminded of Susan Sontag’s contention that all photographs are memento mori: “To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt”5.

I also notice that the trick of parallax (and concurrently, the evocativeness) works most pronouncedly on the figures in the foreground, probably due to the camera angle and vanishing points of the perspective. Behind the two white youngsters, almost fading into the darkness, is a black man, holding up a drill over all of their heads that seems to penetrate the tunnel of rock in which they are suspended.

He appears to have moved during the shot as his face is blurred. This could also be due to the low light in the shaft. Though he is looking straight at me, I can’t connect with him like I do with the figures in front. He is very much in the background, a presence without substance. The way the photo was set up and taken has placed him in that position, and this viewpoint is indelible, no matter how hard I try to look past it.

There is no writing on this one except for what seems to be a reference number: “C269”. The figure in the foreground is a black man, miming work with a mallet and chisel against the rock face, though clearly standing very still for the shot, as he is perfectly in focus, his sceptical gaze on us, a sharp shadow thrown on the rock behind him. This is no ordinary lamp light: it seems clear that these pictures have been professionally illumined by the photographer, perhaps using magnesium flares, because these shots definitely predate flash photography.

To the man with the chisel’s left stands a white man, face dark with dirt. He is holding a lamp in one hand, and his other grasps a support pile which bisects the shaft and also the photo. Tight-jawed, he stares beyond us, his eyes preoccupied, glazed over. Behind the two men in the foreground, there are more men – parts of two, perhaps three workers can be seen, one a black man crouched down at the rock face behind the man with the chisel.

What strikes me most trenchantly about this picture — the punctum, after Barthes7 — is the man with the chisel’s bare feet. He is at work in an extremely hazardous environment without shoes. Looking at all the photographs, every white worker is wearing boots, but there are several pictures where it is visible that many of the black workers are barefoot.

This is shocking visual evidence of an exploitative industry which does not take its workers’ safety seriously: these men are placed at incredible risk without the provision of adequate protective attire: none have hard protection for their heads, and black workers are without shoes. Men not deemed worthy of protection are, by inference, expendable. From these photos, one surmises that black lives are more dispensable than white.

I am really curious to find out more about these pictures. Perhaps the visual evidence here is echoed in literature? Perhaps they can tell us things the literature does not?

Who were these people posing? There is nothing on the back of the photos. No captions, no dates. Who was the photographer? For what purpose were these pictures being taken? The lack of answers to these most mundane of questions lends the photos an uncanny, almost spectral quality.

Directed by: Nina Hartmann and Margaret Chardiet.

Four days before New York noise musician Margaret Chardiet was supposed to leave for her first European tour as Pharmakon, she had a medical emergency which resulted in a major surgery. Suddenly, instead of getting on a plane, she was bedridden for three weeks, missing an organ.

“After seeing internal photographs taken during the surgery, I became hyperaware of the complex network of systems just beneath the skin, any of which were liable to fail or falter at any time,” Chardiet said. “It all happened so fast and unexpectedly that my mind took a while to catch up to the reality of my recovery. I felt a widening divide between my physical and mental self. It was as though my body had betrayed me, acting as a separate entity from my consciousness. I thought of my corporeal body anthropomorphically, with a will or intent of its own, outside of my will’s control, and seeking to sabotage. I began to explore the idea of the conscious mind as a stranger inside an autonomous vessel, and the tension that exists between these two versions of the self.”

Consumed by these ideas, and unable to leave her bed, Chardiet occupied herself by writing the lyrics and music that would become Bestial Burden, the second Pharmakon LP for Sacred Bones Records. The record is a harrowing collection of deeply personal industrial noise tracks, each one brimming with struggle and weighted with the intensity of Chardiet’s internal conflict.

Release date: 10/14/2014

Listen to the full album HERE.

The Wits Anthropology Department is pleased to reopen its Museum collection with

If we burn there is ash

An exhibition by Talya Lubinsky

with contributing artists Meghan Judge, Tshegofatso Mabaso and Thandiwe Msebenzi

and performances by Lebohang Masango and Healer Oran

Wits Anthropology Museum

Wednesday 7 September 2016

18:00

Walkabout with the artists Thursday 8 September 11:30-13:00

All welcome

__

On Christmas Eve of 1931 a fire broke out at Wits University’s Great Hall. At the time, the façade of the Great Hall had been built, its stone pillars and steps creating a striking image of the university in the young colonial city. But the University had run out of funds, and the building that would become Central Block, had not yet been built. Erected behind the grand façade of the Great Hall were wooden shack-like structures, which burned in the fire. These wooden structures housed the collections of what is now called the Cullen Library, as well as the Ethnographic Museum’s collection. Initiated by Winifred Hoernle, head of the Ethnography Museum at the time, the collection was largely comprised of pieces of material culture sent to her from the British missionary, William Burton, while stationed in the ‘Congo’ region.

The fire burned hundreds of books, paintings and artefacts. Some of the only objects that survived the fire are clay burial bowls from the Burton collection. Able to withstand the heat precisely because of their prior exposure to fire, these bowls remain, but are blackened and broken by the 1931 fire.

The exhibition, If we burn, there is ash centres around this story as a place from which to think about the value of colonial collections of material culture. While the origins of the 1931 fire remain unknown, it nonetheless provides a space in which to think about the potentially generative qualities of fire.

Ash, the material remains of fire, however elusive, does not disappear. Even when things burn, they are never fully physically or ephemerally eliminated. Ash is not just the physical remains of that which has been burnt. It is also used as an ingredient in cement mixtures. It is literally transformed into a building material.

Using ash and cement as a poetic relation, this exhibition asks about the potentiality of burning in the project of building and growth. Ash and cement serve as a provocation on the question of what is to be done with the material remains of a violent colonial past.

__

For further information, please contact Talya Lubinsky (talya.lubinsky@gmail.com) or Kelly Gillespie (Kelly.Gillespie@wits.ac.za)

… We set things aside without knowing we are doing so; that is precisely where the danger lies. Or, which is still worse, we set them aside by an act of the will, but by an act of the will that is furtive in relation to ourselves. Afterwards we do not any longer know that we have set anything aside. We do not want to know it, and, by dint of not wanting to know it, we reach the point of not being able to know it.

… We set things aside without knowing we are doing so; that is precisely where the danger lies. Or, which is still worse, we set them aside by an act of the will, but by an act of the will that is furtive in relation to ourselves. Afterwards we do not any longer know that we have set anything aside. We do not want to know it, and, by dint of not wanting to know it, we reach the point of not being able to know it.

This faculty of setting things aside opens the door to every sort of crime. Outside those departments where education and training have forged solid links, it provides a key to absolute licence. That is what makes it possible for men to behave in such an incoherent fashion, particularly wherever the social, collective emotions play a part (war, national or class hatreds, patriotism for a party or a church). Whatever is surrounded with the prestige of the social element is set in a different place from other things and is exempt from certain connexions.

We also make use of this key when we give way to the allurements of pleasure.

I use it when, day after day, I put off the fulfillment of some obligation. I separate the obligation and the passage of time.

There is nothing more desirable than to get rid of this key. It should be thrown to the bottom of a well whence it can never again be recovered.

The ring of Gyges who has become invisible—this is precisely the act of setting aside: setting oneself aside from the crime one commits; not establishing the connexion between the two.

The act of throwing away the key, of throwing away the ring of Gyges—this is the effort proper to the will. It is the act by which, in pain and blindness, we make our way out of the cave. Gyges: ‘I have become king, and the other king has been assassinated.’ No connexion whatever between these two things. There we have the ring!

The owner of a factory: ‘I enjoy this and that expensive luxury and my workmen are miserably poor.’ He may be very sincerely sorry for his workmen and yet not form the connexion.

For no connexion is formed if thought does not bring it about. Two and two remain indefinitely as two and two unless thought adds them together to make them into four.

We hate the people who try to make us form the connexions we do not want to form.

Justice consists of establishing between analogous things connexions identical with those between similar terms, even when some of these things concern us personally and are an object of attachment for us.

This virtue is situated at the point of contact of the natural and the supernatural. It belongs to the realm of the will and of clear understanding, hence it is part of the cave (for our clarity is a twilight), but we cannot hold on to it unless we pass into the light.

__

Excerpted from Simone Weil‘s Gravity and Grace. First French edition 1947. Translated by Emma Crawford. English language edition 1963. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London.

More ridiculous amazingness at bargainbinblasphemy.tumblr.com.

A poem by Louise Westerhout, accompanied by Lliezel Ellick (cello) and Rosemary Lombard (autoharp), performed on 28 July 2016 at the Blah Blah Bar’s Open Mouth night.

Next time we’ll make sure we find a venue where rude men at the bar are not entitled to talk through performances…

A version of the Rezsö Seress classic that we performed on 28 July 2016 as part of a collective which included Louise Westerhout, Lliezel Ellick, Rosemary Lombard, Debra Pryor and Roxanne de Freitas, at Blah Blah Bar’s “Open Mouth” night. We had had just two rehearsals, and I feel like this has the potential to go a lot further… Watch this space!

Off The Last Werewolf, (2011, Six Degrees Records / Crammed Discs).

Soundtrack/companion album to the novel The Last Werewolf by Glen Duncan.

Produced By: Monkey Frog Media

Music By: The Real Tuesday Weld

Published by: Six Degrees Records & Crammed Disks

The Coming Insurrection, a notorious 2007 ultra-left polemical tract written by a collective of French anti-state communists writing under the group-moniker The Invisible Committee, posits a conception of insurrection as the creation of new collective ontologies through acts of radical social rupture. Eschewing the orthodox Marxist line that revolution is something temporally removed from the present, towards which pro-revolutionaries must organize and work, The Invisible Committee’s use of insurrection claims it as an antagonistic challenge to late-capitalism firmly grounded in its own immediacy. Communism is therefore made immediate, and it is willed into being by insurrectionary acts of social rupture.

The Coming Insurrection, a notorious 2007 ultra-left polemical tract written by a collective of French anti-state communists writing under the group-moniker The Invisible Committee, posits a conception of insurrection as the creation of new collective ontologies through acts of radical social rupture. Eschewing the orthodox Marxist line that revolution is something temporally removed from the present, towards which pro-revolutionaries must organize and work, The Invisible Committee’s use of insurrection claims it as an antagonistic challenge to late-capitalism firmly grounded in its own immediacy. Communism is therefore made immediate, and it is willed into being by insurrectionary acts of social rupture.

While much has been written on the debt that The Invisible Committee owes to French strains of ultra-left anti-state communism, Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze, Giorgio Agamben, Situationism, and the Italian Autonomia movement of the 1970s, their implicit nod to the sociopolitical themes of music has been largely ignored. By subtly claiming that insurrection spreads by resonance and that such proliferation “takes the shape of a music,” The Invisible Committee allows for the interpretation of its “coming insurrection” as an inherently musical act. Using a historical reading of the shift from tonality to atonality in Western art music, as exemplified by Arnold Schoenberg, Alden Wood’s interpretation of The Coming Insurrection aims at imbuing its explicitly political premises with a more thorough exploration of its implicit musical qualities.

Published in Interdisciplinary Humanities Vol. 30 pp. 57-65, 2013.

Two Solutions for One Problem (Persian: دو راه حل برای يک مسئله , Dow Rahehal Baraye yek Massaleh) is an Iranian short film from 1975, directed by Abbas Kiarostami, who died yesterday.

During breaktime, Dara and Nader have an altercation about a torn exercise book that the former has given back to the latter. There are two possible outcomes, which the film shows one after the other.

Quite apart from the barbarities and blood baths perpetrated by the Christian nations among themselves throughout European history, the European has also to answer for all the crimes he has committed against the dark-skinned peoples during the process of colonization.

In this respect the white man carries a very heavy burden indeed.

It shows us a picture of the common human shadow that could hardly be painted in blacker colors.

The evil that comes to light in man and that undoubtedly dwells within him is of gigantic proportions, so that for the Church to talk of original sin and to trace it back to Adam’s relatively innocent slip-up with Eve is almost a euphemism.

The case is far graver and is grossly underestimated.

Since it is universally believed that man is merely what his consciousness knows of itself, he regards himself as harmless and so adds stupidity to iniquity. He does not deny that terrible things have happened and still go on happening, but it is always “the others” who do them.

And when such deeds belong to the recent or remote past, they quickly and conveniently sink into the sea of forgetfulness, and that state of chronic woolly-mindedness returns which we describe as “normality.”

In shocking contrast to this is the fact that nothing has finally disappeared and nothing has been made good.

The evil, the guilt, the profound unease of conscience, the obscure misgiving are there before our eyes, if only we would see. Man has done these things; I am a man, who has his share of human nature; therefore I am guilty with the rest and bear unaltered and indelibly within me the capacity and the inclination to do them again at any time.

Even if, juristically speaking, we were not accessories to the crime, we are always, thanks to our human nature, potential criminals.

In reality we merely lacked a suitable opportunity to be drawn into the infernal melée. None of us stands outside humanity’s black collective shadow.

Whether the crime lies many generations back or happens today, it remains the symptom of a disposition that is always and everywhere present – and one would therefore do well to possess some “imagination in evil”, for only the fool can permanently neglect the conditions of his own nature.

In fact, this negligence is the best means of making him an instrument of evil.

Harmlessness and naïveté are as little helpful as it would be for a cholera patient and those in his vicinity to remain unconscious of the contagiousness of the disease.

On the contrary, they lead to projection of the unrecognized evil into the “other.”

This strengthens the opponent’s position in the most effective way, because the projection carries the fear which we involuntarily and secretly feel for our own evil over to the other side and considerably increases the formidableness of his threat.

What is even worse, our lack of insight deprives us of the capacity to deal with evil.

Here, of course, we come up against one of the main prejudices of the Christian tradition, and one that is a great stumbling block to our policies.

We should, so we are told, eschew evil and, if possible, neither touch nor mention it. For evil is also the thing of ill omen, that which is tabooed and feared.

This attitude towards evil, and the apparent circumventing of it, flatter the primitive tendency in us to shut our eyes to evil and drive it over some frontier or other, like the Old Testament scapegoat, which was supposed to carry the evil into the wilderness.

But if one can no longer avoid the realization that evil, without man’s ever having chosen it, is lodged in human nature itself, then it bestrides the psychological stage as the equal and opposite partner of good.

This realization leads straight to a psychological dualism, already unconsciously prefigured in the political world schism and in the even more unconscious dissociation in modern man himself. The dualism does not come from this realization; rather, we are in a split condition to begin with.

It would be an insufferable thought that we had to take personal responsibility for so much guiltiness. We therefore prefer to localize the evil with individual criminals or groups of criminals, while washing our hands in innocence and ignoring the general proclivity to evil.

This sanctimoniousness cannot be kept up, in the long run, because the evil, as experience shows, lies in man – unless, in accordance with the Christian view, one is willing to postulate a metaphysical principle of evil.

The great advantage of this view is that it exonerates man’s conscience of too heavy a responsibility and fobs it off on the devil, in correct psychological appreciation of the fact that man is much more the victim of his psychic constitution than its inventor.

Considering that the evil of our day puts everything that has ever agonized mankind in the deepest shade, one must ask oneself how it is that, for all our progress in the administration of justice, in medicine and in technology, for all our concern for life and health, monstrous engines of destruction have been invented which could easily exterminate the human race.

No one will maintain that the atomic physicists are a pack of criminals because it is to their efforts that we owe that peculiar flower of human ingenuity, the hydrogen bomb.

The vast amount of intellectual work that went into the development of nuclear physics was put forth by men who devoted themselves to their task with the greatest exertions and self-sacrifice and whose moral achievement could just as easily have earned them the merit of inventing something useful and beneficial to humanity.

But even though the first step along the road to a momentous invention may be the outcome of a conscious decision, here, as everywhere, the spontaneous idea – the hunch or intuition – plays an important part.

In other words, the unconscious collaborates too and often makes decisive contributions.

So it is not the conscious effort alone that is responsible for the result; somewhere or other the unconscious, with its barely discernible goals and intentions, has its finger in the pie.

If it puts a weapon in your hand, it is aiming at some kind of violence.

Knowledge of the truth is the foremost goal of science, and if in pursuit of the longing for light we stumble upon an immense danger, then one has the impression more of fatality than of premeditation.

It is not that present-day man is capable of greater evil than the man of antiquity or the primitive. He merely has incomparably more effective means with which to realize his proclivity to evil.

As his consciousness has broadened and differentiated, so his moral nature has lagged behind. That is the great problem before us today. Reason alone does not suffice.

— From The Undiscovered Self (1957).

I sometimes fear that

people think that fascism arrives in fancy dress

worn by grotesques and monsters

as played out in endless re-runs of the Nazis.

Fascism arrives as your friend.

It will restore your honour,

make you feel proud,

protect your house,

give you a job,

clean up the neighbourhood,

remind you of how great you once were,

clear out the venal and the corrupt,

remove anything you feel is unlike you…

It doesn’t walk in saying,

“Our programme means militias, mass imprisonments, transportations, war and persecution.”

From HERE.