I wish right now that I could spew a wry little poem, like those you do

But what’s churning round in me is only a terribly fervent prayer:

Please get home safely through this rain

Please can neither of us die

Before we are friends again

Category Archives: writing

jacky bowring – a field guide to melancholy (2008)

“Melancholy is a twilight state; suffering melts into it and becomes a sombre joy. Melancholy is the pleasure of being sad.”

– Victor Hugo, Toilers of the Sea

Melancholy is ambivalent and contradictory. Although it seems at once a very familiar term, it is extraordinarily elusive and enigmatic. It is something found not only in humans – whether pathological, psychological, or a mere passing mood – but in landscapes, seasons, and sounds. They too can be melancholy. Batman, Pierrot, and Hamlet are all melancholic characters, with traits like darkness, unrequited longing, and genius or heroism. Twilight, autumn and minor chords are also melancholy, evoking poignancy and the passing of time.

How is melancholy defined? A Field Guide to Melancholy traces out some of the historic traditions of melancholy, most of which remain today, revealing it to be an incredibly complex term. Samuel Johnson’s definition, in his eighteenth century Dictionary of the English Language, reveals melancholy’s multi-faceted nature was already well established by then: ‘A disease, supposed to proceed from a redundance of black bile; a kind of madness, in which the mind is always fixed on one object; a gloomy, pensive, discontented temper.’2 All of these aspects – disease, madness and temperament – continue to coalesce in the concept of melancholy, and rather than seeking a definitive definition or chronology, or a discipline-specific account, this book embraces contradiction and paradox: the very kernel of melancholy itself.

As an explicit promotion of the ideal of melancholy, the Field Guide extols the benefits of the pursuit of sadness, and questions the obsession with happiness in contemporary society. Rather than seeking an ‘architecture of happiness’, or resorting to Prozac-with-everything, it is proposed that melancholy is not a negative emotion, which for much of history it wasn’t – it was a desirable condition, sought for its ‘sweetness’ and intensity. It remains an important point of balance – a counter to the ‘loss of sadness’. Not grief, not mourning, not sorrow, yet all of those things.

Melancholy is profoundly interdisciplinary, and ranges across fields as diverse as medicine, literature, art, design, psychology and philosophy. It is over two millennia old as a concept, and its development predates the emergence of disciplines.While similarly enduring concepts have also been tackled by a breadth of disciplines such as philosophy, art and literature, melancholy alone extends across the spectrum of arts and sciences, with significant discourses in fields like psychiatry, as much as in art. Concepts with such an extensive period of development (the idea of ‘beauty’ for example) tend to go through a process of metamorphosis and end up meaning something distinctly different.3 Melancholy has been surprisingly stable. Despite the depth and breadth of investigation, the questions, ideas and contradictions which form the ‘constellation’4 of melancholy today are not dramatically different from those at any time in its history. There is a sense that, as psychoanalytical theorist Julia Kristeva puts it, melancholy is ‘essential and trans-historical’.5

Melancholy is a central characteristic of the human condition, and Hildegard of Bingen, the twelfth century abbess and mystic, believed it to have been formed at the moment that Adam sinned in taking the apple – when melancholy ‘curdled in his blood’.6 Modern day Slovenian philosopher, Slavoj Žižek, also positions melancholy, and its concern with loss and longing, at the very heart of the human condition, stating ‘melancholy (disappointment with all positive, empirical objects, none of which can satisfy our desire) is in fact the beginning of philosophy.’7

The complexity of the idea of melancholy means that it has oscillated between attempts to define it scientifically, and its embodiment within a more poetic ideal. As a very coarse generalisation, the scientific/psychological underpinnings of melancholy dominated the early period, from the late centuries BC when ideas on medicine were being formulated, while in later, mainly post-medieval times, the literary ideal became more significant. In recent decades, the rise of psychiatry has re-emphasised the scientific dimensions of melancholy. It was never a case of either/or, however, and both ideals, along with a multitude of other colourings, have persisted through history.

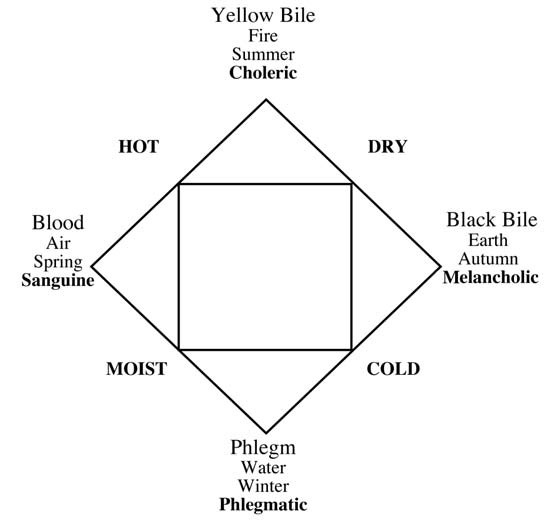

The essential nature of melancholy as a bodily as well as a purely mental state is grounded in the foundation of ideas on physiology; that it somehow relates to the body itself. These ideas are rooted in the ancient notion of ‘humours’. In Greek and Roman times humoralism was the foundation for an understanding of physiology, with the four humours ruling the body’s characteristics.

Phlegm, blood, yellow bile and black bile were believed to be the four governing elements, and each was ascribed to particular seasons, elements and temperaments. This can be expressed via a tetrad, or four-cornered diagram.

The Four Humours, adapted from Henry E Sigerist (1961) “A History of Medicine”, 2 vols New York: Oxford University Press, 2:232

The four-part divisions of temperament were echoed in a number of ways, as in the work of Alkindus, the ninth century Arab philosopher, who aligned the times of the day with particular dispositions. The tetrad could therefore be further embellished, with the first quarter of the day sanguine, second choleric, third melancholic and finally phlegmatic. Astrological allegiances reinforce the idea of four quadrants, so that Jupiter is sanguine, Mars choleric, Saturn is melancholy, and the moon or Venus is phlegmatic. The organs, too, are associated with the points of the humoric tetrad, with the liver sanguine, the gall bladder choleric, the spleen melancholic, and the brain/ lungs phlegmatic.

Melancholy, then, is associated with twilight, autumn, earth, the spleen, coldness and dryness, and the planet Saturn. All of these elements weave in and out of the history of melancholy, appearing in mythology, astrology, medicine, literature and art.The complementary humours and temperaments were sometimes hypothesised as balances, so that the opposite of one might be introduced as a remedy for an excess of another. For melancholy, the introduction of sanguine elements – blood, air and warmth – could counter the darkness. This could also work at an astrological level, as in the appearance of the magic square of Jupiter on the wall behind Albrecht Dürer’s iconic engraving Melencolia I, (1514) – the sign of Jupiter to introduce a sanguine balance to the saturnine melancholy angel.

In this early phase of the development of humoral thinking a key tension arose, as on one hand it was devised as a means of establishing degrees of wellness, but on the other it was a system of types of disposition. As Klibansky, Panofsky and Saxl put it, there were two quite different meanings to the terms sanguine, choleric, phlegmatic and melancholy, as either ‘pathological states or constitutional aptitudes’.9 Melancholy became far more connected with the idea of illness than the other temperaments, and was considered a ‘special problem’.

The blurry boundary between an illness and a mere temperament was a result of the fact that many of the symptoms of ‘melancholia’ were mental, and thus difficult to objectify, unlike something as apparent as a disfigurement or wound. The theory of the humours morphed into psychology and physiognomy, with particular traits or appearances associated with each temperament.

Melancholy was aligned with ‘the lisping, the bald, the stuttering and the hirsute’, and ‘emotional disturbances’ were considered as indicators of ‘mental melancholy’.10 Hippocrates in his Aphorismata, or ‘Aphorisms’, in 400 BC noted, ‘Constant anxiety and depression are signs of melancholy.’ Two centuries later the physician Galen, in an uncharacteristically succinct summation, noted that Hippocrates was ‘right in summing up all melancholy symptoms in the two following: Fear and Depression.’11

The foundations of the ideas on melancholy are fraught with complexity and contradiction, and this signals the beginning of a legacy of richness and debate. We have a love-hate relationship with melancholy, recognising its potential, yet fearing its connotations. What is needed is some kind of guide book, to know how to recognise it, where to find it – akin to the Observer’s Guides, the Blue Guides, or Gavin Pretor-Pinney’s The Cloudspotter’s Guide. Yet, to attempt to write a guide to such an amorphous concept as melancholy is overwhelmingly impossible, such is the breadth and depth of the topic, the disciplinary territories, the disputes, and the extensive creative outpourings. There is a tremendous sense of the infinite, like staring at stars, or at a room full of files, a daunting multitude. The approach is, therefore, to adopt the notion of the ‘constellation’, and to plot various points and co-ordinates, a join-the-dots approach to exploration which roams far and wide, and connects ideas and examples in a way which seeks new combinations and sometimes unexpected juxtapositions.

A Field Guide to Melancholy is therefore in itself a melancholic enterprise: for the writer, and the reader, the very idea of a ‘field guide’ to something so contradictory, so elusive, embodies the impossibility and futility that is central to melancholy’s yearning. Yet, it is this intangible, potent possibility which creates melancholy’s magnetism, recalling Joseph Campbell’s version of the Buddhist advice to “joyfully participate in the sorrows of the world”.12

Notes

1. Victor Hugo, Toilers of the Sea, vol. 3, p.159.

2. Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language, p.458, emphasis mine.

3. This constant shift in the development of concepts is well-illustrated by Umberto Eco (ed) (2004) History of Beauty, New York: Rizzoli, and his recent (2007) On Ugliness, New York: Rizzoli.

4. The term ‘constellation’ is Giorgio Agamben’s, and captures the sense of melancholy’s persistence as a collection of ideas, rather than one simple definition. See Giorgio Agamben, Stanzas:Word and Phantasm in Western Culture, p.19.

5. Julia Kristeva, Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia, p.258.

6. Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky and Fritz Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion and Art, p.79.

7. Slavoj Žižek, Did Somebody say Totalitarianism? Five Interventions on the (Mis)use of a Notion, p.148.

8. In Stanley W Jackson (1986), Melancholia and Depression: From Hippocratic Times to Modern Times, p.9.

9. Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky and Fritz Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion and Art, p.12.

10. ibid, p.15.

11. ibid, p.15, and n.42.

12. A phrase used by Campbell in his lectures, for example on the DVD Joseph Campbell (1998) Sukhavati. Acacia.

__

Excerpted from the introduction to Jacky Bowring’s A Field Guide to Melancholy, Oldcastle Books, 2008.

jesca hoop – seed of wonder (acoustic version, 2008)

From Kismet Acoustic (Phantom Sound & Vision, 2008).

louise bourgeois on the difficulty of expression

How are you going to turn this around and make the stone say what you want when it is there to say “no” to everything? It forbids you. You want a hole, it refuses to make a hole. You want it smooth, it breaks under the hammer. It is the stone that is aggressive. It is a constant source of refusal. You have to win the shape…

Gaston Bachelard would explain this by saying that the thing that had to be said was so difficult and so painful that you have to hack it out of yourself and so you hack it out of the material, a very, very hard material.

I read Bachelard when I was over seventy-five. If I had read Bachelard before, I would have been a different person, I would not have been divided inside since I would have taken the materials, with their different characters, and I would have been more friendly towards them. In the past, every time somebody asked me about materials, I used to answer, “What interests me is what I want to say and I will battle with any material to express accurately what I want to say.” But the medium is always a matter of makeshift solutions. That is, you try everything, you use every material around, and usually they repulse you. Finally, you get one that will work for you. And it is usually the softer ones–lead, plaster, malleable things. That is to say that you start with the harder thing and life teaches you that you had better buckle down, be contented with softer things, softer ways.

__

Excerpted from Louise Bourgeois’ Destruction of the Father / Reconstruction of the Father: Writings and Interviews 1923-1997.

More about Louise Bourgeois’ soft sculpture faces and the restorative act of joining things together HERE.

kathy acker – from “my mother: demonology” (1994)

But the desire you have for me cuts off my breath – These blind eyes see you, and no one else – My blind eyes see how desire is contorting your mouth – They see your mad eyes-

To see. I must see your face, which is enough for me, and now I don’t need anything else.

None of this is realizable.

As soon as I knew this, I agreed that we had to meet in person.

But at the moment we met, all was over. At that moment, I no longer felt anything. I became calm. (I who’ve been searching so hard for calmness.)

I can’t be calm, simple, for more than a moment when I’m with you. Because of want. Because your eyes are holes. In want, everything is always being risked; being is being overturned and ends up on the other side.

It’s me who’s let me play with fire: whatever is ‘I’ are the remnants. I’ve never considered any results before those results happened.

At this moment if I could only roll myself under your feet, I would, and the whole world would see what I am…,

Etc.

Etc.

Do you see how easy it is for me to ask to be regarded as low and dirty? To ask to be spat upon? This isn’t… The sluttishness… But the language of a woman who thinks: it’s a role. I’ve always thought for myself. I’m a woman who’s alone, outside the accepted. Outside the Law, which is language. This is the only role that allows me to be intelligent as I am and to avoid persecution.

But now I’m not thinking for myself, because my life is disintegrating right under me. My inability to bear that lie is what’s giving me strength. Even when I believed in meaning, when I felt defined by opposition between desire and the search for self-knowledge and self-reclamation was tearing me apart, even back then I knew that I was only lying, that I was lying superbly, disgustingly, triumphally.

Life doesn’t exist inside language: too bad for me.

__

Excerpted from Kathy Acker’s My Mother: Demonology, A Novel (pp 252-3). (1994)

Based loosely on the relationship between Colette Peignot and Georges Bataille, My Mother: Demonology is the powerful story of a woman’s struggle with the contradictory impulses for love and solitude. At the dawn of her adult life, Laure becomes involved in a passionate and all-consuming love affair with her companion, B. But this ultimately leaves her dissatisfied, as she acknowledges her need to establish an identity independent of her relationship with him.

Yearning to better understand herself, Laure embarks on a journey of self-discovery, an odyssey that takes her into the territory of her past, into memories and fantasies of childhood, into wildness and witchcraft, into a world where the power of dreams can transcend the legacies of the past and confront the dilemmas of the present.

With a poet’s attention to the power of language and a keen sense of the dislocation that can occur when the narrative encompasses violence and pornography, as well as the traumas of childhood memory, Kathy Acker here takes another major step toward establishing her vision of a new literary aesthetic.

“Memories do not obey the law of linear time,” reads one of the many aphorisms in this novel, and it seems a key point of departure for Acker’s unconventional exploration of memory and its manifestations in dreams. Here, a woman tries to come to terms with her vulnerability and with the excess mental baggage conferred by time. But that simple narrative is just one of the many important levels in the work, which also contains vast psychological wallpaper. Visceral, unflinching, wildly experimental with shifting contexts and settings, this is written in the “punk” style for which Acker (In Memoriam to Identity , LJ 7/90) is well known. Forget categories, though. Her formidably talented hand gives the cacophonous materials compelling poetic rhythm and balance.

laure – (untitled)

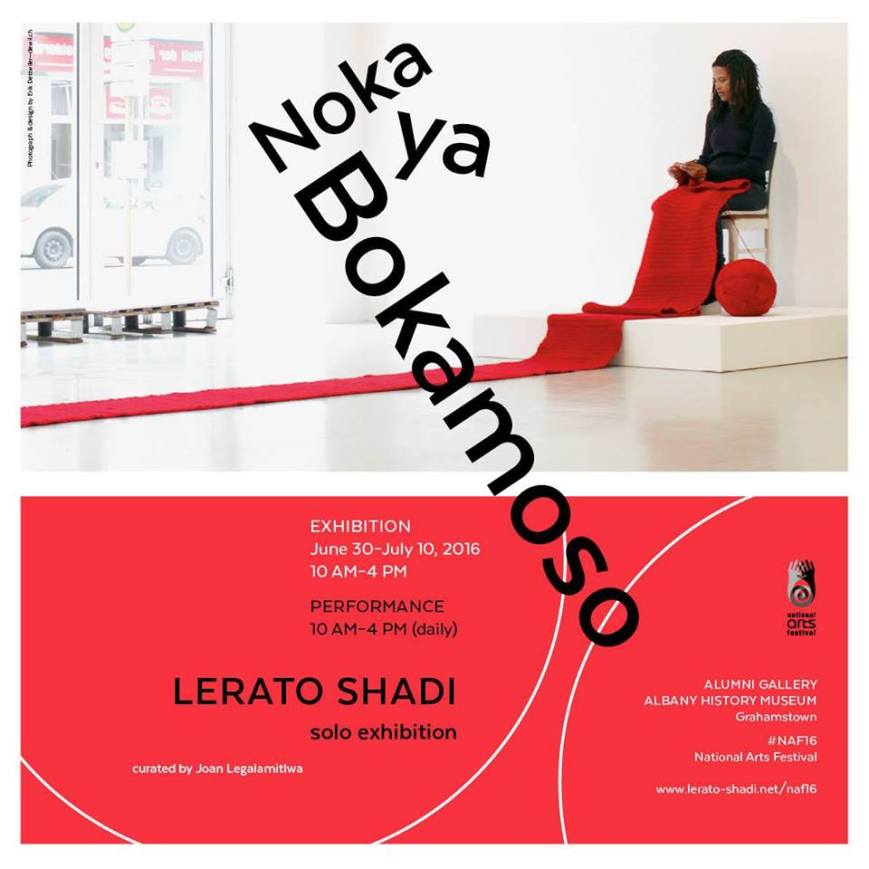

opening tomorrow: lerato shadi – noka ya bokamoso

NOKA YA BOKAMOSO: A SOLO EXHIBITION BY LERATO SHADI

2016 National Arts Festival – Grahamstown

Alumni Gallery, Albany History Museum

30 June – 10 July

Lerato Shadi invites you to her latest solo exhibition and debut National Arts Festival appearance, Noka Ya Bokamoso. This exhibition by the Mahikeng born, Berlin based video and performance artist is one of the six visual art showcases chosen for the main programme.

The exhibition features four of Shadi’s latest works; two performative installations Makhubu and Mosako Wa Nako as well as two video works Sugar & Salt and Untitled.

Curator, Joan Legalamitlwa says,

“The works on the show were purposefully selected as they weave together history as told by and through the Black female body, in its truest and sincerest form, as it should be. Noka Ya Bokamoso is about the Black subject being in control of its own narrative and also about encouraging the visitors to do some introspection when it comes to matters of identity and representation.”

Makhubu is a work performed in the days preceding the festival, executed in absence of an audience. This performance involves Shadi arduously writing in concentric circles with a red pencil, then erasing the writing, leaving traces of the text on the wall and red remnants of the rubber eraser on the floor. This work looks at the historical erasure of the Black subject within the context of Grahamstown’s problematic history as well as historic erasure in the national narrative and how that has impacted on the kinds of stories that we currently tell. The absence of an audience becomes a corporeal metaphor, emphasising the ways in which South Africans, continue to construct a sense of nationhood unaware of significant violent acts that have shaped them.

For Mosako Wa Nako, Shadi will be seated one end of the gallery space for an uninterrupted six hours a day, over the eleven days of the Festival, crocheting what looks like be a red woollen carpet. Sugar & Salt, a video work featuring Shadi and her mother consuming a mineral in the form of salt and a carbohydrate in the form of sugar, makes references to the complexities and intricacies of mother-daughter relationships.

Untitled, Shadi’s latest video work, having its world premiere at the National Arts Festival, will be shot on location in her home village of Lotlhakane, in June 2016. The work consists of a two channel video work conceptualised in three parts: the first deals with the utmost extremes of individual resistance; the second deals with how Shadi experiences the impact of colonial language; the final part is an allegory of resistance.

Shadi’s work explores problematic assumptions projected onto the Black female body and how performance, video and installation create a space for artists to engage with those preconceived notions, making the body both visible and invisible. Using time, repetitive actions as well as stillness, she questions, ‘How does one create oneself?’ rather than allowing others or history to shape one’s person.

The key aim of Noka Ya Bokamoso is to re-center Shadi’s works to its primary audience – the South African audience. Shadi has practiced and exhibited in New York, Bern, Dakar, Moscow and Scotland and now seeks to utilise her work to foster and encourage dialogue around questions of historical knowledge production and its inclusion and exclusion of certain subjects. Her ultimate goal is that she, along with her audiences, will be encouraged not only to consume, but consciously engage in the processes of unearthing subsumed histories and producing critical knowledge.

Lerato Shadi lives and works in Berlin. She completed a BFA in Fine Art from the University of Johannesburg. She was included in The Generational: ‘Younger Than Jesus’ artists directory published by the New Museum, New York. In 2010 she was awarded a Pro Helvetia residency in Bern. In the same year she had her solo exhibition Mosako Wa Seipone at Goethe on Main in Johannesburg. From 2010 to 2012 she was a member of the Bag Factory artist studios in Johannesburg. In 2012 her work was featured at the Dak’art Biennale in Dakar, Senegal and in the III Moscow International Biennale. She is a fellow of Sommerakademie 2013 (Zentrum Paul Klee) and completed in the same year a residency program by invitation of INIVA at Hospitalfield (supported by ROSL). In 2014 she was awarded with the mart stam studio grant. She is currently completing her MFA at the Kunsthochschule Berlin Weissensee.

Noka Ya Bokamoso is made possible through the generous support of the National Arts Festival.

katie collins – woven into the fabric of the text (2016)

The following is excerpted from a feature essay on the LSE blog by Katie Collins, entitled “Woven into the Fabric of the Text: Subversive Material Metaphors in Academic Writing”. Collins proposes that we shift our thinking about academic writing from building metaphors – the language of frameworks, foundations and buttresses – to stitching, sewing and piecing. Needlecraft metaphors offer another way of thinking about the creative and generative practice of academic writing as decentred, able to accommodate multiple sources and with greater space for the feminine voice.

__

[W]hy do I regard switching from a metaphor of building to one of stitching as a subversive act? For several reasons. Throughout history, needlework has been a marker of femininity in its various iterations, a means to inculcate it, and something to sneer at as a way of shoring up women’s supposed inferiority. Theodore Roethke described women’s poetry as ‘the embroidering of trivial themes […] running between the boudoir and the alter, stamping a tiny foot against God…’ (165), for example. Women’s naturally nimble fingers were to be occupied; we were to be kept out of the way and out of trouble, shut in the top room of a circular tower and thus prevented from engaging in the masculine pursuits of politics, thinking, reading and writing and making Art (for a fascinating discussion on women, folk art and cultural femicide, I recommend this post by Dr Lucy Allen). The frills and fripperies our needles produced were ample evidence, should anyone require it, that we were frivolous creatures entirely unsuited to public life. Or so the story was. So using needlework metaphors in my academic writing blows a resonant raspberry to that notion, for one thing. But the subversion here is not as straightforward as reclamation, of presenting something usually disparaged as having value after all. Femininity and its inculcation is a displeasingly twisted yarn of benevolence and belittlement. The trick is to unpick the knots without snapping the thread and unravelling the beautiful work, to value that which has been constructed as feminine while at the same time escaping its constricting net.

Imagining academic writing as piecing fragments is one way of recognising that it can integrate all sorts of sources but, more significantly, piecing is also a decentred activity. When quilting, one can plan, cut and stitch many individual squares whenever there is a moment spare, before bringing them together to form the overall pattern, which is flat and in aesthetic terms may have no centre or many centres, and no predetermined start or end. This holds true both for the practice of quilting and how we might think differently about academic writing, with each contribution not a brick in a structured wall but a square ready to stitch onto other squares to make something expected or unexpected, the goal depth and intensity rather than progress (see Mara Witzling). There is sedition here in several senses. This way of imagining how writing works is not individualistic or competitive. Each voice is a thread, and only when they are woven together do they form a whole, as Ann Hamilton’s tapestries represent social collaboration and interconnectedness; many voices not one, cut from the same cloth or different.

But acknowledging that one might have to fit the work of writing around other things, a problem that has occupied me from the moment I became a mother, is a particularly rebellious act, I think. As Adrienne Rich expresses in the poem ‘Transcendental Etude’:

Vision begins to happen in such a life

as if a woman quietly walked away

from the argument and jargon in a room

and sitting down in the kitchen, began turning in her lap

bits of yarn, calico and velvet scraps,

laying them out absently on the scrubbed boards

in the lamplight, with small rainbow-colored shells

sent in cotton-wool from somewhere far away,

and skeins of milkweed from the nearest meadow –

original domestic silk, the finest findings.

This way of imagining academic writing as something that is part of life, rather than something apart, challenges the view of the scholar as the extraordinary, solitary genius who sits alone in his study day after day while the minutiae of clothing and food is organised for him, around him, despite him. But with metaphors that emphasise the piecing of fragments, both everyday and exceptional, we recognise a way of working in which every fragment that can be pieced together into a square is ‘the preservation of a woman’s voice’.

Read the whole of this great essay by Katie Collins HERE.

simone weil – algebra

Money, mechanization, algebra. The three monsters of contemporary civilization. Complete analogy.

Money, mechanization, algebra. The three monsters of contemporary civilization. Complete analogy.

Algebra and money are essentially levellers, the first intellectually, the second effectively.

About fifty years ago the life of the Provençal peasants ceased to be like that of the Greek peasants described by Hesiod. The destruction of science as conceived by the Greeks took place at about the same period. Money and algebra triumphed simultaneously.

The relation of the sign to the thing signified is being destroyed, the game of exchanges between signs is being multiplied of itself and for itself. And the increasing complication demands that there should be signs for signs… [Note that this comment comes decades before Baudrillard writes about simulacra in 1981.]

Among the characteristics of the modern world we must not forget the impossibility of thinking in concrete terms of the relationship between effort and the result of effort. There are too many intermediaries. As in the other cases, this relationship which does not lie in any thought, lies in a thing: money.

As collective thought cannot exist as thought, it passes into things (signs, machines…). Hence the paradox: it is the thing which thinks and the man who is reduced to the state of a thing.

There is no collective thought. On the other hand our science is collective like our technics. Specialization. We inherit not only results but methods which we do not understand. For the matter of that the two are inseparable, for the results of algebra provide methods for the other sciences.

To make an inventory or criticism of our civilization—what does that mean? To try to expose in precise terms the trap which has made man the slave of his own inventions. How has unconsciousness infiltrated itself into methodical thought and action?

To escape by a return to the primitive state is a lazy solution. We have to rediscover the original pact between the spirit and the world in this very civilization of which we form a part. But it is a task which is beyond our power on account of the shortness of life and the impossibility of collaboration and of succession. That is no reason for not undertaking it. The situation of all of us is comparable to that of Socrates when he was awaiting death in his prison and began to learn to play the lyre… At any rate we shall have lived…

The spirit, overcome by the weight of quantity, has no longer any other criterion than efficiency.

Modern life is given over to immoderation. Immoderation invades everything: actions and thought, public and private life.

The decadence of art is due to it. There is no more balance anywhere. The Catholic movement is to some extent in reaction against this; the Catholic ceremonies, at least, have remained intact. But then they are unrelated to the rest of existence.

Capitalism has brought about the emancipation of collective humanity with respect to nature. But this collective humanity has itself taken on with respect to the individual the oppressive function formerly exercised by nature.

This is true even with material things: fire, water etc. The community has taken possession of all these natural forces.

Question: can this emancipation, won by society, be transferred to the individual?

__

Excerpted from Simone Weil‘s Gravity and Grace. First French edition 1947. Translated by Emma Crawford. English language edition 1963. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London.

simone weil – beauty

Beauty is the harmony of chance and the good.

Beauty is the harmony of chance and the good.

Beauty is necessity which, while remaining in conformity with its own law and with that alone, is obedient to the good.

The subject of science is the beautiful (that is to say order, proportion, harmony) in so far as it is suprasensible and necessary.

The subject of art is sensible and contingent beauty discerned through the network of chance and evil.

The beautiful in nature is a union of the sensible impression and of the sense of necessity. Things must be like that (in the first place), and, precisely, they are like that.

Beauty captivates the flesh in order to obtain permission to pass right to the soul.

Among other unions of contraries found in beauty there is that of the instantaneous and the eternal.

The beautiful is that which we can contemplate. A statue, a picture which we can gaze at for hours.

The beautiful is something on which we can fix our attention. Gregorian music. When the same things are sung for hours each day and every day, whatever falls even slightly short of supreme excellence becomes unendurable and is eliminated.

The Greeks looked at their temples. We can endure the statues in the Luxembourg because we do not look at them. A picture such as one could place in the cell of a criminal sentenced to solitary confinement for life without it being an atrocity, on the contrary.

Only drama without movement is truly beautiful. Shakespeare’s tragedies are second-class with the exception of Lear. Those of Racine, third-class except for Phèdre. Those of Corneille of the nth class.

A work of art has an author and yet, when it is perfect, it has something which is essentially anonymous about it. It imitates the anonymity of divine art. In the same way the beauty of the world proves there to be a God who is personal and impersonal at the same time and is neither the one nor the other separately.

The beautiful is a carnal attraction which keeps us at a distance and implies a renunciation. This includes the renunciation of that which is most deep-seated, the imagination. We want to eat all the other objects of desire. The beautiful is that which we desire without wishing to eat it. We desire that it should be.

We have to remain quite still and unite ourselves with that which we desire yet do not approach. We unite ourselves to God in this way: we cannot approach him.

Distance is the soul of the beautiful.

The attitude of looking and waiting is the attitude which corresponds with the beautiful. As long as one can go on conceiving, wishing, longing, the beautiful does not appear. That is why in all beauty we find contradiction, bitterness and absence which are irreducible.

Poetry: impossible pain and joy. A poignant touch, nostalgia. Such is Provençal and English poetry. A joy which by reason of its unmixed purity hurts, a pain which by reason of its unmixed purity brings peace.

Beauty: a fruit which we look at without trying to seize it.

The same with an affliction which we contemplate without drawing back.

A double movement of descent: to do again, out of love, what gravity does. Is not the double movement of descent the key to all art?*

This movement of descent, the mirror of grace, is the essence of all music. All the rest only serves to enshrine it.

The rising of the notes is a purely sensorial rising. The descent is at the same time a sensorial descent and a spiritual rising. Here we have the paradise which every being longs for: where the slope of nature makes us rise towards the good.

In everything which gives us the pure authentic feeling of beauty there really is the presence of God. There is as it were an incarnation of God in the world and it is indicated by beauty.

The beautiful is the experimental proof that the incarnation is possible.

Hence all art of the highest order is religious in essence. (That is what people have forgotten today.) A Gregorian melody is as powerful a witness as the death of a martyr.

If the beautiful is the real presence of God in matter and if contact with the beautiful is a sacrament in the full sense of the word, how is it that there are so many perverted aesthetes? Nero. Is it like the hunger of those who frequent black masses for the consecrated hosts? Or is it, more probably, because these people do not devote themselves to what is genuinely beautiful, but to a bad imitation? For, just as there, is an art which is divine, so there is one which is demoniacal. It was no doubt the latter that Nero loved. A great deal of our art is of the devil.

A person who is passionately fond of music may quite well be a perverted person—but I should find it hard to believe this of any one who thirsted for Gregorian chanting. [hahaha!]

We must certainly have committed crimes which have made us accursed, since we have lost all the poetry of the universe.

Art has no immediate future because all art is collective and there is no more collective life (there are only dead collections of people), and also because of this breaking of the true pact between the body and the soul. Greek art coincided with the beginning of geometry and with athleticism, the art of the Middle Ages with the craftsmen’s guilds, the art of the Renaissance with the beginning of mechanics, etc. … Since 1914 there has been a complete cut. Even comedy is almost impossible. There is only room for satire (when was it easier to understand Juvenal?).

Art will never be reborn except from amidst a general anarchy— it will be epic no doubt, because affliction will have simplified a great many things… Is it therefore quite useless for you to envy Leonardo or Bach. Greatness in our times must take a different course. Moreover it can only be solitary, obscure and without an echo… (but without an echo, no art).

__

* Descendit ad inferos… So, in another order, great art redeems gravity by espousing it out of love. [Editor’s note.]

__

Excerpted from Simone Weil‘s Gravity and Grace. First French edition 1947. Translated by Emma Crawford. English language edition 1963. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London.

a lacanian interpretation of sartre’s ‘erostratus’ (1939)

Read Jean Paul Sartre’s short story Erostratus, written the year after his famous Nausea, HERE.

Jordan Alexander Hill on the story from a psychoanalytical perspective:

Jean-Paul Sartre’s “Erostratus” may be the shortest story in The Wall, yet it serves as a fitting psychoanalytic case-study. “Erostratus” tells the story of Paul Hilbert, a lonely man plagued by insecurity and sexual impotency, who attempts and ultimately fails to commit a heinous crime. Shortly into the story, it becomes clear that the crime is mostly an attempt to escape his mediocrity through an act of powerful self-assertion. We will look at this story not only through a traditional psychoanalytic lens, but also by applying important Lacanian principles. Sartre, who developed his own “existential” brand of psychoanalysis, surely wrote “Erostratus” to support certain phenomenological and ethical themes from Being and Nothingness—we’ll look at some of these perspectives. However, in many ways, we arrive at the deepest understanding of Hilbert and his motivations by bringing Lacanian theories into the discussion. In this paper, we first locate the basic existential and psychoanalytic themes that underpin “Erostratus”, in addition to looking at Lacan’s “mirror phase” and how this relates to Hilbert’s social development. “Erostratus” is essentially a story about narcissism, alienation, otherness, and desire. Lacan’s psychic structures—particularly the imaginary and symbolic orders—will give us a sense of where these emotions come from, how they affect our protagonist, and how they function in the larger narrative.

Like in many “existential” works, our protagonist is a bland working class guy with a routine existence and a mundane job. He has no friends to speak of and is a self-professed “anti-humanist”. As Hilbert’s impatience with his situation grows, he decides he must make a statement that will prove his anti-humanism and secure his name in the history books—he will murder six random people on a busy street in Paris. Hilbert is deeply moved by the ancient Greek story of “Erostratus,” which tells of a man who burned down the temple of Artemis at Ephesus to immortalize himself. What strikes him is that while nobody knows the name of the man who built the temple of Artemis, everyone remembers Erostratus, the man who destroyed it. The rest of the story follows Hilbert’s metamorphosis, as the day of his crime draws nearer. In what follows, Hilbert buys a gun and carries it around in public, becoming sexually aroused by the possibilities, and the power he now possesses. He becomes more and more obsessed with this power and even visits a prostitute, commanding her to walk around naked at gunpoint (he does this several times, each time ejaculating in his pants). As the day of his crime draws nearer, Hilbert spends his life savings on expensive meals and prostitutes, and even mails letters of his murderous intent to 102 famous French writers. Yet, in the end, Hilbert is incapable of following through. He winds up shooting only one man, a “big man”, and has a frantic meltdown in the street afterward. The story ends in a café lavatory, as Hilbert gives himself up to the police.

Let us first take a look at some of the elements that make up the “existential” composure of the story. Hilbert’s act of mailing letters to famous writers before committing his crime shows a deep insecurity over the potential legacy he wishes to leave. Hilbert must have others verify and be witness to his crime for the weight of his actions to seem real to him. In existential thought, this is an offense known as “being-for-others” (we’ll return to this later when we discuss Lacan). Hilbert no longer lives in a world where his actions and choices hold any real weight or significance. This lack of self-determination plunges Hilbert into a kind of moral nihilism, which only exacerbates his problems. Another significant element to note is the rise in power Hilbert feels as he buys a gun and brings it around with him wherever he goes. The angst or dread that follows—often described in existential circles as being a kind of “excitement or fear over the possibility of one’s own freedom”—is an important aspect of Hilbert’s condition. Furthermore, one would not have to use queer theory, nor is it beyond any stretch of the imagination, to assert that Sartre uses the gun here as a phallic symbol. For Hilbert, happiness truly is a warm gun, as the gun symbolizes the power he has always lacked socially and sexually. The fact that Hilbert makes prostitutes walk around naked at gun point, without letting them touch or look at him, is another teller. This voyeuristic behavior, according to Sartre, is a mechanism by which the individual avoids his or her own subjectivity—shirking responsibility—in order to live through the imagined subjectivity of another (Sartre, 1953, 244). Hilbert, it turns out, suffers in large part from a staggering lack of being (this “lack of being” doesn’t stem from any shortage of self-consciousness, but rather from a case of what I’ll call “mistaken identity,” in a Lacanian sense).

Hilbert’s crime, we come to find out, is not motivated by material gain or political ideology. What, then, is it motivated by? To start, let’s look at our protagonist’s own self-identification: Hilbert believes his crime is motivated by his “anti-humanism”. In the letter, he congratulates the famous authors for being humanists, for loving men. “You have humanism in your blood…” Hilbert writes, “You are delighted when your neighbor takes a cup from the table because there is a way of taking it which is strictly human… less supple, less rapid than that of a monkey”. He goes on to sarcastically praise the authors for relieving and consoling the masses. “People throw themselves greedily at your books… they think of a great love, which you bring them and that makes up for many things, for being ugly, for being cowardly, for being cuckolded, for not getting a raise on the first of January”. These sound like Hilbert’s own problems.

Later in the letter, Hilbert explains his own hatred of humanity. “I cannot love them… what attracts you to them disgusts me… men chewing slowly, all the while keeping an eye on everything, the left hand leafing through an economic review. Is it my fault I prefer to watch the sea-lions feeding?”. Given this, it would be a mistake to equate Hilbert’s anti-humanism to misanthropy. The word “misanthrope” is normally an intellectual self-label, which is defined by a general disgust with the thoughtlessness or lack of social awareness perceived in others. As Moliere notes in his Les Misanthrope: “I detest all men; Some because they are wicked and do evil, Others because they tolerate the wicked” (Moliere, I.i.). Hilbert, on the other hand, is not a misanthrope; he is a self-reflective watcher, a voyeur. And his anti-humanism—his “all-too-humanness” as he puts it it—seems to involve the hatred of those physical and emotional qualities which he observes in others, and which he himself cannot experience. Hilbert’s condition is strikingly similar to Sartre’s analysis of the poet Baudelaire. “For most of us,” Sartre contends, “it is enough to see the tree or house; we forget ourselves” (Sartre, 1950, 22). Baudelaire, however, “was the man who never forgot himself” (Sartre, 1950, 22). Hilbert, likewise, is too self-conscious to experience normal human emotions. He does not simply see things; but sees himself seeing things. As such, he has lost the unselfconscious grace and naturalness he so despises in others.

This deep self-consciousness, this narcissism, is something that alienates Hilbert, and makes normal communication with others almost impossible. If we asked Lacan, he would probably point us to the mirror phase and the imaginary order, which are both significant in Hilbert’s case. The mirror phase refers to a period in psychosexual development, when “the child for the first time becomes aware, through seeing its image in the mirror” (Homer 24). For Lacan, this marks the emergence of the ego, as the child realizes it can control the movements of this new image. This should not be confused with the advent of “selfhood,” but rather it is a moment of profound alienation, where we actually mistake this new mirror-image for our “self” (Homer 25).

Read more of this article HERE (and read the actual story HERE).

simone weil – metaxu

All created things refuse to be for me as ends. Such is God’s extreme mercy towards me. And that very thing is what constitutes evil. Evil is the form which God’s mercy takes in this world.

All created things refuse to be for me as ends. Such is God’s extreme mercy towards me. And that very thing is what constitutes evil. Evil is the form which God’s mercy takes in this world.

This world is the closed door. It is a barrier. And at the same time it is the way through.

Two prisoners whose cells adjoin communicate with each other by knocking on the wall. The wall is the thing which separates them but it is also their means of communication. It is the same with us and God. Every separation is a link.

By putting all our desire for good into a thing we make that thing a condition of our existence. But we do not on that account make of it a good. Merely to exist is not enough for us.

The essence of created things is to be intermediaries. They are intermediaries leading from one to the other and there is no end to this. They are intermediaries leading to God. We have to experience them as such.

The bridges of the Greeks. We have inherited them but we do not know how to use them. We thought they were intended to have houses built upon them. We have erected skyscrapers on them to which we ceaselessly add storeys. We no longer know that they are bridges, things made so that we may pass along them, and that by passing along them we go towards God.

Only he who loves God with a supernatural love can look upon means simply as means.

Power (and money, power’s master key) is means at its purest. For that very reason, it is the supreme end for all those who have not understood.

This world, the realm of necessity, offers us absolutely nothing except means. Our will is for ever sent from one means to another like a billiard ball.

All our desires are contradictory, like the desire for food. I want the person I love to love me. If, however, he is totally devoted to me, he does not exist any longer, and I cease to love him. And as long as he is not totally devoted to me he does not love me enough. Hunger and repletion.

Desire is evil and illusory, yet without desire we should not seek for that which is truly absolute, truly boundless. We have to have experienced it. Misery of those beings from whom fatigue takes away that supplementary energy which is the source of desire.

Misery also of those who are blinded by desire. We have to fix our desire to the axis of the poles.

What is it a sacrilege to destroy? Not that which is base, for that is of no importance. Not that which is high, for, even should we want to, we cannot touch that. The metaxu. The metaxu form the region of good and evil.

No human being should be deprived of his metaxu, that is to say of those relative and mixed blessings (home, country, traditions, culture, etc.) which warm and nourish the soul and without which, short of sainthood, a human life is not possible.

The true earthly blessings are metaxu. We can respect those of others only in so far as we regard those we ourselves possess as metaxu. This implies that we are already making our way towards the point where it is possible to do without them. For example, if we are to respect foreign countries, we must make of our own country, not an idol, but a stepping-stone towards God.

All the faculties being freely exercised without becoming mixed, starting from a single, unique principle. It is the microcosm, the imitation of the world. Christ according to Saint Thomas. The just man of the Republic. When Plato speaks of specialization he speaks of the specialization of man’s faculties and not of the specialization of men; the same applies to hierarchy. The temporal having no meaning except by and for the spiritual, but not being mixed with the spiritual—leading to it by nostalgia, by reaching beyond itself. It is the temporal seen as a bridge, a metaxu. It is the Greek and Provençal vocation.

Civilization of the Greeks. No adoration of force. The temporal was only a bridge. Among the states of the soul they did not seek intensity but purity.

__

Excerpted from Simone Weil‘s Gravity and Grace. First French edition 1947. Translated by Emma Crawford. English language edition 1963. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London.

simone weil – meaning of the universe*

We are a part which has to imitate the whole.

We are a part which has to imitate the whole.

The a¯tman. Let the soul of a man take the whole universe for its body. Let its relation to the whole universe be like that of a collector to his collection, or of one of the soldiers who died crying out ‘Long live the Emperor!’ to Napoleon. The soul transports itself outside the actual body into something else. Let it therefore transport itself into the whole universe.

We should identify ourselves with the universe itself. Everything that is less than the universe is subject to suffering.

Even though I die, the universe continues. That does not console me if I am anything other than the universe. If, however, the universe is, as it were, another body to my soul, my death ceases to have any more importance for me than that of a stranger. The same is true of my sufferings.

Let the whole universe be for me, in relation to my body, what the stick of a blind man is in relation to his hand. His sensibility is really no longer in his hand but at the end of the stick. An apprenticeship is necessary.

To limit one’s love to the pure object is the same thing as to extend it to the whole universe.

To change the relationship between ourselves and the world in the same way as, through apprenticeship, the workman changes the relationship between himself and the tool. Getting hurt: this is the trade entering into the body. May all suffering make the universe enter into the body.

Habit, skill: a transference of the consciousness into an object other than the body itself.

May this object be the universe, the seasons, the sun, the stars. The relationship between the body and the tool changes during apprenticeship. We have to change the relationship between our body and the world.

We do not become detached, we change our attachment. We must attach ourselves to the all.

We have to feel the universe through each sensation. What does it matter then whether it be pleasure or pain? If our hand is shaken by a beloved friend when we meet again after a long separation, what does it matter that he squeezes it hard and hurts us?

There is a degree of pain on reaching which we lose the world. But afterwards peace comes. And if the paroxysm returns, so does the peace which follows it. If we realize this, that very degree of pain turns into an expectation of peace, and as a result does not break our contact with the world.

Two tendencies with opposite extremes: to destroy the self for the sake of the universe, or to destroy the universe for the sake of the self. He who has not been able to become nothing runs the risk of reaching a moment when everything other than himself ceases to exist.

External necessity or an inner need as imperative as that of breathing. ‘Let us become the central breath.’ Even if a pain in our chest makes respiration extremely painful, we still breathe, we cannot help it.

We have to associate the rhythm of the life of the body with that of the world, to feel this association constantly and to feel also the perpetual exchange of matter by which the human being bathes in the world.

Things which nothing can take from a human being as long as he lives: in the way of movement over which his will has a hold, respiration; in the way of perception, space (even in a dungeon, even with our eyes blinded and our ear-drums pierced, as long as we live we are aware of space).

We have to attach to these things the thoughts which we desire that no circumstances should be able to deprive us of.

To love our neighbour as ourselves does not mean that we should love all people equally, for I do not have an equal love for all the modes of existence of myself. Nor does it mean that we should never make them suffer, for I do not refuse to make myself suffer. But we should have with each person the relationship of one conception of the universe to another conception of the universe, and not to a part of the universe.

Not to accept an event in the world is to wish that the world did not exist. That is within my power—for myself. If I wish it I obtain it. I am then an excrescence produced by the world.

Wishes in folklore: what makes wishes dangerous is the fact that they are granted. To wish that the world did not exist is to wish that I, just as I am, may be everything.

Would that the entire universe, from this pebble at my feet to the most distant stars, existed for me at every moment as much as Agnès did for Arnolphe or his money-box did for Harpagon. If I choose, the world can belong to me like the treasure does to the miser. But it is a treasure that does not increase.

This irreducible ‘I’ which is the irreducible basis of my suffering—I have to make this ‘I’ universal.

What does it matter that there should never be joy in me since there is perfect joy perpetually in God! And the same is true with regard to beauty, intelligence and all things.

To desire one’s salvation is wrong, not because it is selfish (it is not in man’s power to be selfish), but because it is an orientation of the soul towards a merely particular and contingent possibility instead of towards a completeness of being, instead of towards the good which exists unconditionally.

All that I wish for exists, or has existed, or will exist somewhere. For I am incapable of complete invention. In that case how should I not be satisfied?

Br . . . I could not prevent myself from imagining him living, imagining his house as a possible place for me to listen to his delightful conversation. Thus the consciousness of the fact of his death made a frightful desert. Cold with metallic coldness. What did it matter to me that there were other people to love? The love that I directed towards him, together with the outlines shaping in my mind of exchanges of ideas which could take place with no one else, were without an object. Now I no longer imagine him as alive and his death has ceased to be intolerable for me. The memory of him is sweet to me. But there are others whom I did not know then and whose death would affect me in the same way.

D . . . is not dead, but the friendship that I bore him is dead, and a like sorrow goes with it. He is no more than a shadow.

But I cannot imagine the same transformation for X . . ., Y . . ., Z . . ., who, nevertheless, so short a time ago did not exist in my consciousness.

Just as parents find it impossible to realize that three years ago their child was non-existent, I find it impossible to realize that I have not always known the beings I love.

I think I must love wrongly: otherwise things would not seem like this to me. My love would not be attached to a few beings. It would be extended to everything which is worthy of love.

‘Be ye perfect even as your Father who is in heaven. . . .’ Love in the same way as the sun gives light. Love has to be brought back to ourselves in order that it may be shed on all things. God alone loves all things and he only loves himself.

To love in God is far more difficult than we think.

I can taint the whole universe with my wretchedness without feeling it or collecting it together within myself.

We have to endure the discordance between imagination and fact. It is better to say ‘I am suffering’ than ‘this landscape is ugly’.

We must not want to change our own weight in the balance of the world—the golden balance of Zeus.

The whole cow gives milk although the milk is only drawn from the udder. In the same way the world is the producer of saintliness.

__

* The identification of the soul with the universe has no connexion here with pantheism. One can only fully accept the blind necessity which rules the universe by holding closely through love to the God who transcends the universe. Cf. above: ‘This world, in so far as it is quite empty of God, is God himself.’ [Editor’s note.]

__

Excerpted from Simone Weil‘s Gravity and Grace. First French edition 1947. Translated by Emma Crawford. English language edition 1963. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London.

simone weil – training

We have to accomplish the possible in order to touch the impossible. The correct exercise (according to our duty) of the natural faculties of will, love and knowledge is, in relation to spiritual realities, exactly what the movement of the body is in relation to the perception of tangible objects. A paralyzed man lacks this perception.

We have to accomplish the possible in order to touch the impossible. The correct exercise (according to our duty) of the natural faculties of will, love and knowledge is, in relation to spiritual realities, exactly what the movement of the body is in relation to the perception of tangible objects. A paralyzed man lacks this perception.

The fulfilment of our strictly human duty is of the same order as correctness in the work of drafting, translating, calculating, etc. To be careless about this correctness shows a lack of respect for the object. The same thing applies to neglect of duty.

Those things which have to do with inspiration are the only ones which are the better for delay. Those which have to do with natural duty and the will cannot allow of delay.

Precepts are not given for the sake of being practised, but practice is prescribed in order that precepts may be understood. They are scales. One does not play Bach without having done scales. But neither does one play a scale merely for the sake of the scale.

Training. Every time we catch ourselves involuntarily indulging in a proud thought, we must for a few seconds turn the full gaze of our attention upon the memory of some humiliation in our past life, choosing the most bitter, the most intolerable we can think of.

We must not try to change within ourselves or to efface desires and aversions, pleasures and sorrows. We must submit to them passively, just as we do to the impressions we receive from colours, according no greater credit to them than in the latter case. If my window is red I cannot, though I should reason day and night for a whole year, see my room as anything but pink. I know, moreover, that it is necessary, just and right that I should see it thus. At the same time, as far as information about my room goes, I only accord to the pink colour a credit limited by my knowledge of its relation to the window. I must accept in this way and no other the desires and aversions, pleasures and sorrows of every kind which I find within me.

On the other hand, as we have also a principle of violence in us—that is to say the will—we must also, in a limited measure, but to the full extent of that measure, use this violent principle in a violent way; we must compel ourselves by violence to act as though we had not a certain desire or aversion, without trying to persuade our sensibility—compelling it to obey. This causes it to revolt and we have to endure this revolt passively, taste of it, savour it, accept it as something outside ourselves, as the pink colour of the room with the red window.

Each time that we do violence to ourselves in this spirit we make an advance, slight or great but real, in the work of training the animal within us.

Of course if this violence we do ourselves is really to be of use in our training it must only be a means. When a man trains a dog to perform tricks he does not beat it for the sake of beating it, but in order to train it, and with this in view he only hits it when it fails to carry out a trick. If he beats it without any method he ends by making it unfit for any training, and that is what the wrong sort of asceticism does.

Violence against ourselves is only permissible when it is based on reason (with a view to carrying out what we clearly consider to be our duty)—or when it is enjoined on us through an irresistible impulsion on the part of grace (but then the violence does not come from ourselves).

The source of my difficulties lies in the fact that, through exhaustion and an absence of vital energy, I am below the level of normal activity. And if something takes me and raises me up I am lifted above it. When such moments come it would seem to me a calamity to waste them in ordinary activities. At other times, I should have to do violence to myself with a violence which I cannot succeed in mustering.

I could consent to the anomaly of behaviour resulting from this; but I know, or I believe I know, that I should not do so. It involves crimes of omission towards others. And as for myself, it imprisons me.

What method is there then?

I must practise transforming the sense of effort into a passive sense of suffering. Whatever I may have to bear, when God sends me suffering, I am inescapably forced to suffer all that there is to suffer. Why, when it comes to duty, should I not in like manner do all that there is to be done?

Mountains, rocks, fall upon us and hide us far from the wrath of the Lamb. At the present moment I deserve this wrath.

I must not forget that according to Saint John of the Cross the inspirations which turn us from the accomplishment of easy and humble obligations come from the side of evil.

Duty is given us in order to kill the self—and I allow so precious an instrument to grow rusty.

We must do our duty at the prescribed time in order to believe in the reality of the external world. We must believe in the reality of time. Otherwise we are in a dream.

It is years since I recognized this defect in myself and recognized its importance, and all this time I have done nothing to get rid of it. What excuse can I find?

Has it not been growing in me since I was ten years old? But however great it may be, it is limited. That is enough. If it is great enough to take from me the possibility of wiping it out during this life and so attaining to the state of perfection, that must be accepted just as it is, with an acceptance that is full of love. It is enough that I know that it exists, that it is evil and that it is finite. But to know each of these three things effectively and to know them all three together implies the beginning and the uninterrupted continuation of the process of wiping out. If this process does not begin to show itself, it is a sign that I do not know in truth the very thing that I am writing.

The necessary energy dwells in me, since I live by means of it. I must draw it relentlessly out of myself, even though I should die in so doing.

Uninterrupted interior prayer is the only perfect criterion of good and evil. Everything which does not interrupt it is permitted, everything which interrupts it is forbidden. It is impossible to do harm to others when we act in a state of prayer—on condition that it is true prayer. But before reaching that stage, we must have worn down our own will against the observance of rules.

Hope is the knowledge that the evil we bear within us is finite, that the slightest turning of the will towards good, though it should last but an instant, destroys a little of it, and that, in the spiritual realm, everything good infallibly produces good. Those who do not know this are doomed to the torture of the Danaïds.

Good infallibly produces good, and evil evil, in the purely spiritual realm. On the other hand, in the natural realm, that of psychology included, good and evil reciprocally produce each other. Accordingly we cannot have security until we have reached the spiritual realm—precisely the realm where we can obtain nothing by our own efforts, where we must wait for everything to come to us from outside.

__

1 ‘If thou wilt thou canst make me clean’ (Gospel text).

__

Excerpted from Simone Weil‘s Gravity and Grace. First French edition 1947. Translated by Emma Crawford. English language edition 1963. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London.

félix guattari on writing (1972)

I’m strapped to this journal. Grunt. Heave. Impression that the ship is going down. The furniture slides, the table legs wobble …

Writing so that I won’t die. Or so that I die otherwise. Sentences breaking up. Panting like for what. […]

You can explain everything away. I explain myself away. But to whom? You know … The question of the other. The other and time. I’m home kind of fucking around. Listening to my own words. Redundancy. Peepee poopoo. Things are so fucking weird! […]

Have to be accountable. Yield to arguments. What I feel like is just fucking around. Publish this diary for example. Say stupid shit. Barf out the fucking-around-o-maniacal schizo flow. Barter whatever for whoever wants to read it. Now that I’m turning into a salable name I can find an editor for sure […] Work the feed-back; write right into the real. But not just the professional readers’ real, “Quinzaine polemical” style. The close, hostile real. People around. Fuck shit up. The stakes greater than the oeuvre or they don’t attain it […]

Just setting up the terms of this project makes me feel better. My breathing is freed up by one notch. Intensities. A literary-desiring machine. […]

When it works I have a ton to spare, I don’t give a shit, I lose it as fast as it comes, and I get more. Active forgetting! What matters is interceding when it doesn’t work, when it spins off course, and the sentences are fucked up, and the words disintegrate, and the spelling is total mayhem. Strange feeling, when I was small, with some words. Their meaning would disappear all of a sudden. Panic. And I have to make a text out of that mess and it has to hold up: that is my fundamental schizo-analytic project. Reconstruct myself in the artifice of the text. Among other things, escape the multiple incessant dependencies on images incarnating the “that’s how it goes!”

Writing for nobody? Impossible. You fumble, you stop. I don’t even take the trouble of expressing myself so that when I reread myself I can understand whatever it was I was trying to say. Gilles will figure it out, he’ll work it through. […]

I tell myself I can’t take the plunge and leave this shit for publication because that would inconvenience Gilles. But really, though? I just need to cross out the passages he’s directly involved in. I’m hiding behind this argument so that I can let myself go again and just fucking float along. Even though when it comes to writing an article, I start over like twenty-five times!!

And this dance of anxiety …

From The Anti-Oedipus Papers, a set of notes and journal entries by Félix Guattari written while he and Gilles Deleuze were busy writing Anti-Oedipus together(1972) .Translated from the French by Stéphane Nadaud.

simone weil – intelligence and grace

We know by means of our intelligence that what the intelligence does not comprehend is more real than what it does comprehend.

We know by means of our intelligence that what the intelligence does not comprehend is more real than what it does comprehend.

Faith is the experience that intelligence is enlightened by love.

Only, intelligence has to recognize by the methods proper to it, that is to say by verification and demonstration, the pre-eminence of love. It must not yield unless it knows why, and it must know this quite precisely and clearly. Otherwise its submission is a mistake and that to which it submits itself is something other than supernatural love. For example it may be social influence.

In the intellectual order, the virtue of humility is nothing more nor less than the power of attention.

The wrong humility leads us to believe that we are nothing in so far as we are ourselves—in so far as we are certain particular human beings.

True humility is the knowledge that we are nothing in so far as we are human beings as such, and, more generally, in so far as we are creatures.

The intelligence plays a great part in this. We have to form a conception of the universal.

When we listen to Bach or to a Gregorian melody, all the faculties of the soul become tense and silent in order to apprehend this thing of perfect beauty—each after its own fashion—the intelligence among the rest. It finds nothing in this thing it hears to affirm or deny, but it feeds upon it.

Should not faith be an adherence of this kind?

The mysteries of faith are degraded if they are made into an object of affirmation and negation, when in reality they should be an object of contemplation.

The privileged rôle of the intelligence in real love comes from the fact that it is inherent in the nature of intelligence to become obliterated through the very fact that it is exercised. I can make efforts to discover truths, but when I have them before me they exist and I do not count.

There is nothing nearer to true humility than intelligence. It is impossible to be proud of our intelligence at the moment when we are really exercising it. Moreover, when we do exercise it we are not attached to it, for we know that even if we became an idiot the following instant and remained so for the rest of our life, the truth would continue unchanged.

The mysteries of the Catholic faith are not intended to be believed by all the parts of the soul. The presence of Christ in the host is not a fact of the same kind as the presence of Paul’s soul in Paul’s body (actually both are completely incomprehensible, but not in the same way). The Eucharist should not then be an object of belief for the part of me which apprehends facts. That is where Protestantism is true. But this presence of Christ in the host is not a symbol, for a symbol is the combination of an abstraction and an image, it is something which human intelligence can represent to itself, it is not supernatural. There the Catholics are right, not the Protestants. Only with that part of us which is made for the supernatural should we adhere to these mysteries.

The rôle of the intelligence—that part of us which affirms and denies and formulates opinions—is merely to submit. All that I conceive of as true is less true than those things of which I cannot conceive the truth, but which I love. Saint John of the Cross calls faith a night. With those who have had a Christian education, the lower parts of the soul become attached to these mysteries when they have no right to do so. That is why such people need a purification of which Saint John of the Cross describes the stages. Atheism and incredulity constitute an equivalent of this purification.

The desire to discover something new prevents people from allowing their thoughts to dwell on the transcendent, undemonstrable meaning of what has already been discovered. My total lack of talent which makes such a desire out of the question for me is a great favour I have received. The recognized and accepted lack of intellectual gifts compels the disinterested use of the intelligence.

The object of our search should not be the supernatural, but the world. The supernatural is light itself: if we make an object of it we lower it.

The world is a text with several meanings, and we pass from one meaning to another by a process of work. It must be work in which the body constantly bears a part, as, for example, when we learn the alphabet of a foreign language: this alphabet has to enter into our hand by dint of forming the letters. If this condition is not fulfilled, every change in our way of thinking is illusory.

We have not to choose between opinions. We have to welcome them all but arrange them vertically, placing them on suitable levels.

Thus: chance, destiny, Providence.

Intelligence can never penetrate the mystery, but it, and it alone, can judge of the suitability of the words which express it. For this task it needs to be keener, more discerning, more precise, more exact and more exacting than for any other.

The Greeks believed that only truth was suitable for divine things—not error nor approximations. The divine character of anything made them more exacting with regard to accuracy. (We do precisely the opposite, warped as we are by the habit of propaganda.) It was because they saw geometry as a divine revelation that they invented a rigorous system of demonstration…

In all that has to do with the relations between man and the supernatural we have to seek for a more than mathematical precision; this should be more exact than science.1

We must suppose the rational in the Cartesian sense, that is to say mechanical rule or necessity in its humanly demonstrable form, to be everywhere it is possible to suppose it, in order to bring to light that which lies outside its range.

The use of reason makes things transparent to the mind. We do not, however, see what is transparent. We see that which is opaque through the transparent—the opaque which was hidden when the transparent was not transparent. We see either the dust on the window or the view beyond the window, but never the window itself. Cleaning off the dust only serves to make the view visible. The reason should be employed only to bring us to the true mysteries, the true undemonstrables, which are reality. The uncomprehended hides the incomprehensible and should on this account be eliminated.

Science, today, will either have to seek a source of inspiration higher than itself or perish.

Science only offers three kinds of interest: (1) Technical applications, (2) A game of chess, (3) A road to God. (Attractions are added to the game of chess in the shape of competitions, prizes and medals.)

Pythagoras. Only the mystical conception of geometry could supply the degree of attention necessary for the beginning of such a science. Is it not recognized, moreover, that astronomy issues from astrology and chemistry from alchemy? But we interpret this filiation as an advance, whereas there is a degradation of the attention in it. Transcendental astrology and alchemy are the contemplation of eternal truths in the symbols offered by the stars and the combinations of substances. Astronomy and chemistry are degradations of them. When astrology and alchemy become forms of magic they are still lower degradations of them. Attention only reaches its true dimensions when it is religious.

Galileo. Having as its principle unlimited straight movement and no longer circular movement, modern science could no longer be a bridge towards God.

The philosophical cleansing of the Catholic religion has never been done. In order to do it it would be necessary to be inside and outside.

__

1 Here again is one of those contradictions which can only be resolved in the realm of the inexpressible: the mystic life, which only arises from the divine arbitrariness, is nevertheless subject to the most severe rules. Saint John of the Cross was able to give a geometric plan of the journey of the soul towards God. [Editor’s note.]

__

Excerpted from Simone Weil‘s Gravity and Grace. First French edition 1947. Translated by Emma Crawford. English language edition 1963. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London.

antonio gramsci – history (1916)

Give up to life your every action, your every ounce of faith. Throw all your best energies, sincerely and disinterestedly, into life. Immerse yourselves, living creatures that you are, in the live, pulsing tide of human existence, until you feel at one with it, until it floods through you, and you feel your individual personality as an atom within a body, a vibrating particle within a whole, a violin string which receives and echoes all the symphonies of history; of that history which, in this way, you are helping to create.

Give up to life your every action, your every ounce of faith. Throw all your best energies, sincerely and disinterestedly, into life. Immerse yourselves, living creatures that you are, in the live, pulsing tide of human existence, until you feel at one with it, until it floods through you, and you feel your individual personality as an atom within a body, a vibrating particle within a whole, a violin string which receives and echoes all the symphonies of history; of that history which, in this way, you are helping to create.

In spite of this utter abandonment of the self to the reality which surrounds it, in spite of this attempt to key your individuality into the complex play of universal causes and effects, you may still, suddenly, feel a sense that something is missing; you may become conscious of vague and indefinable needs, those needs which Schopenhauer termed metaphysical.

You are in the world, but you do not know why you are here. You act, but you do not know why. You are conscious of voids in your life; you desire some justification of your being, of your actions; and it seems to you that human reasons alone do not suffice. Tracing the causal links further and further back, you arrive at a point where, to co-ordinate, to regulate the movement, some supreme reason is necessary, some reason which lies beyond what is known and what is knowable. You are just like a man looking at the sky, who, as he moves further and further back through the space while science has mapped out for us, finds ever greater difficulties in his fantastic uncontrolled impulses.