There are cats and cats. – Denis Diderot

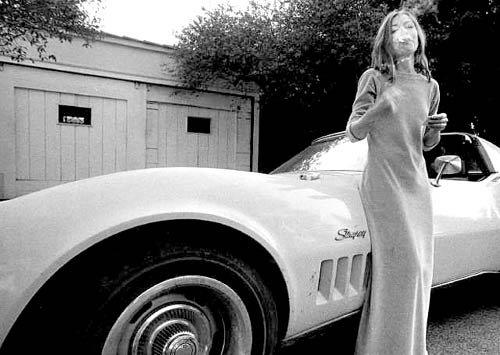

Patricia Highsmith with “Ripley”

W.H. Auden with “Pangur”

“Pangur, white Pangur, How happy we are

Alone together, scholar and cat.”

Aldous Huxley with “Limbo”

“No man ever dared to manifest his boredom so insolently as does a Siamese tomcat when he yawns in the face of his amorously importunate wife.” – Aldous Huxley

Sylvia Plath with “Daddy”

“And I a smiling woman.

I am only thirty.

And like the cat I have nine times to die.”

Doris Lessing with “Black Madonna”

Samuel Beckett with “Murphy” and “Watt”

Mark Twain with “Huckleberry”

George Bernard Shaw with “Pygmalion”

William Carlos Williams with “Adam and Eve”

As the cat

by William Carlos Williams

As the cat

climbed over

the top ofthe jamcloset

first the right

forefootcarefully

then the hind

stepped down

into the pit of

the empty

flowerpot

Gore Vidal with “Caligula”

Randall Jarrell with “Little Friend”

Edward Gorey with “Harp, Brown and Company”

Ezra Pound with his three cats (also tried for high treason after the war)

Tame Cat

by Ezra Pound

It rests me to be among beautiful women

Why should one always lie about such matters?

I repeat:

It rests me to converse with beautiful women

Even though we talk nothing but nonsense,The purring of the invisible antennae

Is both stimulating and delightful.

Ernest Hemingway with “Nick”

Ernest Hemingway had an affinity for many things, his feline companions being one of them. The “Hemingway Cat,” or polydactyl, is a feline that, instead of the normal 18 toes, has six or more toes on the front feet and sometimes an extra toe on the rear. Hemingway had many talents and interests. He was an extreme cat-lover because he admired the spirit and independence of the species. He acquired his first feline from a ship’s captain in Key West, Florida, where he made his home for many years. Today, around 60 felines live at the Ernest Hemingway Museum and Home in Key West. They are protected by the terms left in his will.

Raymond Chandler with “Big Sleep”

Truman Capote with “Tiffany”

“She was still hugging the cat. “Poor slob,” she said, tickling his head, “poor slob without a name. It’s a little inconvenient, his not having a name. But I haven’t any right to give him one: he’ll have to wait until he belongs to somebody. We just sort of took up by the river one day, we don’t belong to each other: he’s an independent, and so am I. I don’t want to own anything until I know I’ve found the place where me and things belong together. I’m not quite sure where that is just yet. But I know what it’s like.” She smiled, and let the cat drop to the floor. “It’s like Tiffany’s,” she said.”

Elizabeth Bishop with “Minnow”

Lullaby for the Cat

by Elizabeth Bishop

Minnow go to sleep and dream,

Close your great big eyes:

Round your bed Events prepare

The pleasentest surprise.Darling Minnow, drop that frown,

Just cooperate.

Not a kitten shall be drowned

In the Marxist State.Joy and Love will both be yours,

Minnow, don’t be glum.

Happy days are coming soon –

Sleep, and let them come . . .

Churchill with “Marmelade”

While many bits of trivia might be known about Winston Churchill, his love of felines isn’t necessarily one of them. Nevertheless, he owned several cats and, during his later years, was particularly fond of Jock, who was a “ginger tom” (a “marmalade cat”). During his time as PM, his best-known cat was a grey called Nelson. During a dinner at the PM’s country residence, Chequers, American war correspondent Quentin Reynolds noted Churchill as saying: “Nelson is the bravest cat I ever knew. I once saw him chase a huge dog out of the Admiralty. I decided to adopt him and name him after our great Admiral.” During dinner, Reynolds noted, “When Mrs. Churchill was not looking, the Prime Minister sneaked pieces of salmon to Nelson.” There were even rumors that Nelson sat in with his master during Cabinet meetings, and Churchill once told a colleague that Nelson was doing more than he was for the war effort.

Allen Ginsberg with “Howl”

“I saw the best cats of my generation destroyed by madness.”

Jack Kerouac with “Tyke”

”Holding up my

purring cat to the moon

I sighed.”

William S. Burroughs with “Junkie”

Charles Bukowski with “Factotum”

The History Of One Tough Motherfucker

by Charles Bukowski (last verse)

I shake the cat, hold him up in

the smoky and drunken light, he’s relaxed he knows…

it’s then that the interviews end

although I am proud sometimes when I see the pictures

later and there I am and there is the cat and we are photo-

graphed together.

he too knows it’s bullshit but that somehow it all helps.

Don Delillo with “Mao II”

Hermann Hesse with “Narciss”

Jorge Luis Borges with “Aleph”

Julio Cortázar with “Bestiario”

Alberto Moravia with “Agostino”

Jospeh Brodsky with “Urania”

Haruki Murakami with

Kafka André Bazin with “Chaplin”

Louis-Ferdinand Céline with “Mea Culpa”

Françoise Sagan with “Brahms”

Jean-Paul Sartre with “Nothing”

Albert Camus with “Stranger”

Jaques Derrida with “Logos”

“Logos, a living, animate creature, is thus also an organism that has been engendered. An organism: a differentiated body proper, with a center and extremities, joints, a head, and feet.” (Jaques Derrida, Plato’s Pharmacy)

Michel Foucault with “Insanity”

Robert Frost

The cat comes into the room.

I put the cat out.

The cat comes in again.

(Robert Frost)

The Ad-dressing of Cats

by T.S. Eliot

You've read of several kinds of Cat,

And my opinion now is that

You should need no interpreter

To understand their character.

You now have learned enough to see

That Cats are much like you and me

And other people whom we find

Possessed of various types of mind.

For some are same and some are mad

And some are good and some are bad

And some are better, some are worse--

But all may be described in verse.

You've seen them both at work and games,

And learnt about their proper names,

Their habits and their habitat:

But how would you ad-dress a Cat?

So first, your memory I'll jog,

And say: A CAT IS NOT A DOG.

And you might now and then supply

Some caviare, or Strassburg Pie,

Some potted grouse, or salmon paste--

He's sure to have his personal taste.

(I know a Cat, who makes a habit

Of eating nothing else but rabbit,

And when he's finished, licks his paws

So's not to waste the onion sauce.)

A Cat's entitled to expect

These evidences of respect.

And so in time you reach your aim,

And finally call him by his NAME.

So this is this, and that is that:

And there's how you AD-DRESS A CAT.

Jean Gaumy

Beautiful pictures from writersandkitties, entry shared from Weimarart

I feel terribly ashamed. I should rename my poor cat, who was ruined to a life of cuteness with a name like Tempura! I should rename her, or add a sassy surname, like Tempura Trenchett, to regain her literary dignity.

How will she feel if she ever had to come across Jean Paul Sartre’s ghost of a cat, “Nothing”!

I only wish I thought of the idea first.

reblogged from pennysparkle

![22hr38min [photo: Niklas Zimmer]C-type print 120x99,4cm (Ed.3) and 60x49,7cm (Ed.7)](https://fleurmach.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/22hr38min-niklas-zimmer.jpg?w=869)