I want to make a praise of sleep. Not as a practitioner—I admit I have never been what is called “a good sleeper” and perhaps we can return later to that curious concept—but as a reader. There is so much sleep to read, there are so many ways to read it. In Aristotle’s view, sleep requires a “daimonic but not a divine” kind of reading. Kant refers to sleep’s content as “involuntary poetry in a healthy state.”

I want to make a praise of sleep. Not as a practitioner—I admit I have never been what is called “a good sleeper” and perhaps we can return later to that curious concept—but as a reader. There is so much sleep to read, there are so many ways to read it. In Aristotle’s view, sleep requires a “daimonic but not a divine” kind of reading. Kant refers to sleep’s content as “involuntary poetry in a healthy state.”

Keats wrote a “Sonnet to Sleep,” invoking its powers against the analytic of the day:

O soft embalmer of the still midnight!

. . . Then save me, or the passed day will shine

Upon my pillow, breeding many woes;

Save me from curious conscience, that still lords

Its strength for darkness, burrowing like a mole;

Turn the key deftly in the oiled wards,

And seal the hushed casket of my soul.

My intention in this essay is to burrow like a mole in different ways of reading sleep, different kinds of readers of sleep, both those who are saved, healthy, daimonic, good sleepers and those who are not. Keats ascribes to sleep an embalming action. This means two things: that sleep does soothe and perfume our nights; that sleep can belie the stench of death inborn in us. Both actions are salvific in Keats’ view. Both deserve (I think) to be praised.

My earliest memory is of a dream. It was in the house where we lived when I was three or four years of age. I dreamed I was asleep in the house in an upper room.

That I awoke and came downstairs and stood in the living room. The lights were on in the living room, although it was hushed and empty. The usual dark green sofa and chairs stood along the usual pale green walls. It was the same old living room as ever, I knew it well, nothing was out of place. And yet it was utterly, certainly, different. Inside its usual appearance the living room was as changed as if it had gone mad.

Later in life, when I was learning to reckon with my father, who was afflicted with and eventually died of dementia, this dream recovered itself to me, I think because it seemed to bespeak the situation of looking at a well-known face, whose appearance is exactly as it should be in every feature and detail, except that it is also, somehow, deeply and glowingly, strange.

The dream of the green living room was my first experience of such strangeness and I find it as uncanny today as I did when I was three. But there was no concept of madness or dementia available to me at that time. So, as far as I can recall, I explained the dream to myself by saying that I had caught the living room sleeping. I had entered it from the sleep side.And it took me years to recognize, or even to frame a question about, why I found this entrance into strangeness so

supremely consoling. For despite the spookiness, inexplicability and later tragic reference of the green living room, it was and remains for me a consolation to think of it lying there, sunk in its greenness, breathing its own order, answerable to no one, apparently penetrable everywhere and yet so perfectly disguised in all the propaganda of its own waking life as to become in a true sense something incognito at the heart of our sleeping house.

It is in these terms that I wish to praise sleep, as a glimpse of something incognito. Both words are important. Incognito means “unrecognized, hidden, unknown.”

Something means not nothing. What is incognito hides from us because it has something worth hiding, or so we judge. As an example of this judgment I shall cite for you two stanzas of Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “The Man-Moth.” The Man- Moth, she says, is a creature who lives most of the time underground but pays occasional visits to the surface of the earth, where he attempts to scale the faces of the buildings and reach the moon, for he understands the moon to be a hole at the top of the sky through which he may escape. Failing to attain the moon each time he falls back and returns to the pale subways of his underground existence.

Here is the poem’s third stanza:

Up the façades,

his shadow dragging like a photographer’s cloth behind him,

he climbs fearfully, thinking that this time he will manage

to push his small head through that round clean opening

and be forced through, as from a tube, in black scrolls on the light.

(Man, standing below him, has no such illusions).

But what the Man-Moth fears most he must do, although

he fails, of course, and falls back scared but quite unhurt.

The Man-Moth is not sleeping, nor is he a dream, but he may represent sleep itself—an action of sleep, sliding up the facades of the world at night on his weird quest. He harbours a secret content, valuable content, which is difficult to extract even if you catch him.

Here is the poem’s final stanza:

If you catch him,

hold up a flashlight to his eye. It’s all dark pupil,

an entire night itself, whose haired horizon tightens

as he stares back, and closes up the eye. Then from the lids

one tear, his only possession, like the bee’s sting, slips.

Slyly he palms it, and if you’re not paying attention

he’ll swallow it. However, if you watch, he’ll hand it over,

cool as from underground springs and pure enough to drink.

To drink the tear of sleep, to detach the prefix “un-” from its canniness and from its underground purposes, has been the project of many technologies and therapies—from the ancient temple of Asklepios at Epidauros, where sick people slept the night in order to dream their own cure, to the psychoanalytic algebras of Jacques Lacan, who understands sleep as a space from which the sleeper can travel in two directions, both of them a kind of waking.

If I were to praise either of these methods of healing I would do so on grounds of their hopefulness. Both Asklepiadic priests and Lacanian analysts posit a continuity between the realms of waking and sleeping, whereby a bit of something incognito may cross over from night to day and change the life of the sleeper. Here is an ancient account of one of the sleep cures at Epidauros:

There came as a suppliant to the god Asklepios a man who was so one eyed that on the left he had only lids, there was nothing, just emptiness. People in the temple laughed at him for thinking he would see with an eye that was not there. But in a vision that appeared to him as he slept, the god seemed to boil some medicine and, drawing apart the lids, poured it in. When day came the man went out, seeing with both eyes.

What could be more hopeful than this story of an empty eye filled with seeing as it sleeps? An analyst of the Lacanian sort might say that the one-eyed man has chosen to travel all the way in the direction of his dream and so awakes to a reality more real than the waking world. He dove into the nothingness of his eye and is awakened by too much light. Lacan would praise sleep as a blindness, which nonetheless looks back at us.

What does sleep see when it looks back at us? This is a question entertained by Virginia Woolf in To the Lighthouse, a novel that falls asleep for twenty-five pages in the middle. The story has three

parts. Parts I and III concern the planning and execution of a trip to the lighthouse by the Ramsay family.

Part II is told entirely from the sleep side. It is called “Time Passes.” It begins as a night that grows into many nights then turns into seasons and years. During this time, changes flow over the house of the story and penetrate the lives of the characters while they sleep. These changes are glimpsed

as if from underneath; Virginia Woolf ’s main narrative is a catalogue of silent bedrooms, motionless chests of drawers, apples left on the dining room table, the wind prying at a window blind, moonlight gliding on floorboards. Down across these phenomena come facts from the waking world, like swimmers stroking by on a night lake. The facts are brief, drastic and enclosed in square brackets.

For example:

[Mr. Ramsay, stumbling along a passage one dark morning, stretched his arms out, but Mrs. Ramsay having died rather suddenly the night before, his arms, though stretched out, remained empty.]

or:

[A shell exploded. Twenty or thirty young men were blown up in France, among them Andrew Ramsay, whose death, mercifully, was instantaneous.]

or:

[Mr. Carmichael brought out a volume of poems that spring, which had an unexpected success. The war, people said, had revived their interest in poetry.]

These square brackets convey surprising information about the Ramsays and their friends, yet they float past the narrative like the muffled shock of a sound heard while sleeping. No one wakes up. Night plunges on, absorbed in its own events. There is no exchange between night and its captives, no tampering with eyelids, no drinking the tear of sleep. Viewed from the sleep side, an empty eye socket is just a fact about a person, not a wish to be fulfilled, not a therapeutic challenge. Virginia Woolf offers us, through sleep, a glimpse of a kind of emptiness that interests her. It is the emptiness of things before we make use of them, a glimpse of reality prior to its efficacy.

Some of her characters also search for this glimpse while they are awake. Lily Briscoe, who is a painter in To the Lighthouse, stands before her canvas and ponders how “to get hold of that very jar on the nerves, the thing itself before it has been made anything.”

In a famous passage of her diaries, Virginia Woolf agrees with the aspiration:

If I could catch the feeling I would: the feeling of the singing of the real world, as one is driven by loneliness and silence from the habitable world.

What would the singing of the real world sound like? What would the thing itself look like? Such questions are entertained by her character Bernard, at the end of The Waves:

“So now, taking upon me the mystery of things, I could go like a spy without leaving this place, without stirring from my chair. . . . The birds sing in chorus; the house is whitened; the sleeper stretches; gradually all is astir. Light floods the room and drives shadow beyond shadow to where they hang in folds inscrutable. What does this central shadow hold? Something? Nothing? I do not know. . . .”

Throughout her fiction Virginia Woolf likes to finger the border between nothing and something. Sleepers are ideal agents of this work.

Read the rest of this brilliant essay: Every Exit is an Entrance from Anne Carson’s Decreation (2005).

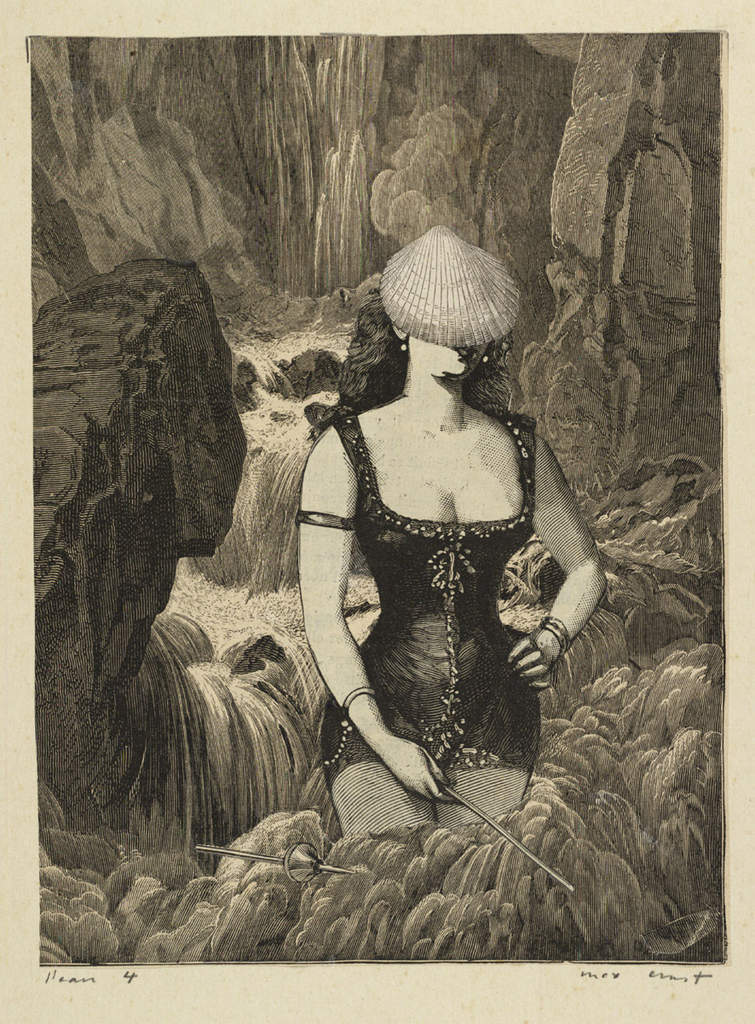

![Max Ernst - Une semaine de bonté [A Week of Kindness]. La clé des chants 1 [The Key of Songs 1] 1933](https://fleurmach.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/003_max_ernst_theredlist.jpg?w=869)