The real in us is silent; the acquired is talkative.

— Kahlil Gibran, from Sand and Foam (1926). You can read the full text HERE.

The real in us is silent; the acquired is talkative.

— Kahlil Gibran, from Sand and Foam (1926). You can read the full text HERE.

Until tonight they were separate specialties, different stories, the best of their own worst.

Until tonight they were separate specialties, different stories, the best of their own worst.

Riding my warm cabin home, I remember Betsy’s laughter; she laughed as you did, Rose, at the first story. Someday, I promised her, I’ll be someone going somewhere, and we plotted it in the humdrum school for proper girls. The next April the plane bucked me like a horse, my elevators turned and fear blew down my throat, that last profane gauge of a stomach coming up. And then returned to land, as unlovely as any seasick sailor, sincerely eighteen; my first story, my funny failure.

Maybe, Rose, there is always another story, better unsaid, grim or flat or predatory.

Half a mile down the lights of the in-between cities turn up their eyes at me. And I remember Betsy’s story, the April night of the civilian air crash and her sudden name misspelled in the evening paper, the interior of shock and the paper gone in the trash ten years now. She used the return ticket I gave her.

This was the rude kill of her; two planes cracking in mid-air over Washington, like blind birds. And the picking up afterwards, the morticians tracking bodies in the Potomac and piecing them like boards to make a leg or a face. There is only her miniature photograph left, too long now for fear to remember. Special tonight because I made her into a story that I grew to know and savor. A reason to worry, Rose, when you fix an old death like that, and outliving the impact, to find you’ve pretended.

We bank over Boston. I am safe. I put on my hat. I am almost someone going home. The story has ended.

(Amen!)

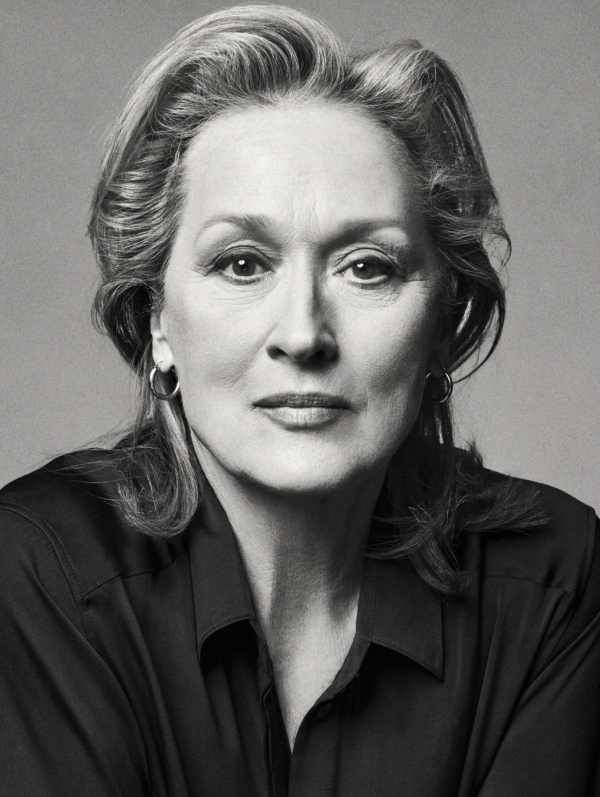

UPDATE, 3 SEPTEMBER: I have just checked and the following quote is actually from the author José Micard Teixeira, but has been widely misattributed to Meryl Streep (apologies — I picked it up on Facebook). However, these words do resonate with Ms Streep’s uncompromising attitude to life, which is why the erroneous attribution has stuck, I guess. I love the sentiment, and am happy to pass this on, whoever said it!

“I no longer have patience for certain things, not because I’ve become arrogant, but simply because I’ve reached a point in my life where I do not want to waste more time with what displeases me or hurts me. I have no patience for cynicism, excessive criticism and demands of any nature. I lost the will to please those who do not like me, to love those who do not love me and to smile at those who do not want to smile at me.

“I no longer have patience for certain things, not because I’ve become arrogant, but simply because I’ve reached a point in my life where I do not want to waste more time with what displeases me or hurts me. I have no patience for cynicism, excessive criticism and demands of any nature. I lost the will to please those who do not like me, to love those who do not love me and to smile at those who do not want to smile at me.

“I no longer spend a single minute on those who lie or want to manipulate. I decided not to coexist anymore with pretense, hypocrisy, dishonesty and cheap praise. I do not tolerate selective erudition nor academic arrogance. I do not adjust either to popular gossiping. I hate conflict and comparisons. I believe in a world of opposites and that’s why I avoid people with rigid and inflexible personalities. In friendship I dislike the lack of loyalty and betrayal. I do not get along with those who do not know how to give a compliment or a word of encouragement. Exaggerations bore me and I have difficulty accepting those who do not like animals. And on top of everything I have no patience for anyone who does not deserve my patience.”

The Archive & Public Culture Research Initiative (where I work) has invited Esther Peeren, author of The Spectral Metaphor: Living Ghosts and the Agency of Invisibility (Palgrave, 2014), for a week of intense discussion, academic exchange and engagement around the theme of the ghost/spectre both as archival metaphor and as conceptual figure in post-colonial and cultural studies.

The Archive & Public Culture Research Initiative (where I work) has invited Esther Peeren, author of The Spectral Metaphor: Living Ghosts and the Agency of Invisibility (Palgrave, 2014), for a week of intense discussion, academic exchange and engagement around the theme of the ghost/spectre both as archival metaphor and as conceptual figure in post-colonial and cultural studies.

Peeren is Associate Professor of Media Studies at the University of Amsterdam, Vice-Director of the Amsterdam Centre for Globalisation Studies (ACGS) and senior researcher at the Amsterdam School for Cultural Analysis (ASCA). Her current research projects explore global spectralities and rural globalization.

On Tuesday, 26 August, she will deliver a lunchtime lecture, Lumumba’s Ghosts: Immaterial Matters and Matters Immaterial in Sven Augustijnen’s Spectres, in the Jon Berndt Thought Space (A17, Arts Block, Upper Campus, University of Cape Town). In her analysis of Belgian artist Sven Augustijnen’s 2011 multi-media exhibition, Spectres (which focuses on the mystery of the 1961 assassination of Patrice Lumumba, the first democratically elected Prime Minister of the independent Republic of the Congo), Peeren argues that a focus on immaterialities-as-spectralities prompts the viewer to take seriously that which is not immediately apprehensible, or deemed inconsequential. At the same time, it transforms our understanding of matter itself, since immateriality is inevitably implied in materiality, both metaphorically (materialities may be considered immaterial, insignificant) and literally (over time, materialities may transform, decay or even disappear).

Appealing to Jacques Derrida’s concept of spectrality, her analysis shows how Augustijnen’s work, especially the feature-length film included in the exhibition, moves the materiality of the immaterial and the immateriality of the material centre stage, and lays out the consequences of this double imbrication for individual and collective understandings of history, memory and the archive.

If you’d like to attend pn 26 August, RSVP to APC-admin@uct.ac.za.

I feel with some passion that what we truly are is private, and almost infinitely complex, and ambiguous, and both external and internal, and double- or triple- or multiply natured, and largely mysterious even to ourselves; and furthermore that what we are is only part of us, because identity, unlike “identity”, must include what we do.

And I think that to find oneself and every aspect of this complexity reduced in the public mind to one property that apparently subsumes all the rest (“gay”, “black”, “Muslim”, whatever) is to be the victim of a piece of extraordinary intellectual vulgarity. Literally vulgar: from vulgus. It’s crowd-thought.

— Philip Pullman

“I don’t agree that I am controversial. What I feel is that most people are not critical thinkers. The society tells them what to believe, what to think…and their knee jerk reactions are guided completely by that conditioning. They usually realize later on that what I’m saying is not controversial… when they take time and think in depth. Even if they don’t agree with me… they understand what I’m saying without all the claims of being shocked by controversy. I’m not a controversial person if you’re a critical thinker.”

Check out Kola Boof’s website, where you can also read more of this interview.

my wrists ache

wrest them

look out

a deck of shards

sick notes

cutting in

cutting up

cutting down

cutting out

cutting off

the pulse

wound up wound

wind up wind

wound up wind

wound down wind

wind down wound

wind up wounded

binds unbound

an unstruck sound

this name means nothing to me

rolling off my glossed tongue

the missing ink

the beads of spittle in the pink

the drown flying in my drink

sink for yourself

sink or blink

outside carries on

the whorl of a banshee

howling at the pane

open your eyes

close your mouth

close your eyes

open your mouth

open your close

eye your mouth

mouth your silence

silence your eyes

make the whirl go away

Go and see this at the Encounters Documentary Festival, on right now in Cape Town and Jo’burg: the brilliant Sarah Polley‘s genre-defying examination of the workings of memory and narrative related to her own family’s secrets. It’s a gentle yet unflinching interrogation of how truth is shaped by the stories we tell ourselves when making sense of the things that happen in our lives. Humorous, poignant, profound… highly recommended.

“While they’re still alive, people can become ghosts.”

— Haruki Murakami, from Kafka on the Shore.

writing kills me.

Here are some excerpts from an interview with Joan Didion that appeared in The Paris Review No. 74, Fall-Winter 1978. She talks about the performative violence of writing, and of the sometimes paralysing self-consciousness that attends it.

Reading her responses, I identified so personally that at points it felt like she could have been writing my own thoughts, down to the constrictions of that harsh Protestant ethic. But I’m not as strong as Joan. The nausea tends to silence me… except when it’s overwhelming: then, I vomit it out, sometimes all over unsuspecting passersby!

I especially liked what she says about how growing up in a dangerous landscape can affect one’s engagement with the world. I have often wondered whether I would be at all like I am if I hadn’t grown up in the turmoil of ’80s and ’90s South Africa. It wasn’t just about the weather, here.

INTERVIEWER

You have said that writing is a hostile act; I have always wanted to ask you why.

JOAN DIDION

It’s hostile in that you’re trying to make somebody see something the way you see it, trying to impose your idea, your picture. It’s hostile to try to wrench around someone else’s mind that way. Quite often you want to tell somebody your dream, your nightmare. Well, nobody wants to hear about someone else’s dream, good or bad; nobody wants to walk around with it. The writer is always tricking the reader into listening to the dream.

INTERVIEWER

Are you conscious of the reader as you write? Do you write listening to the reader listening to you?

DIDION

Obviously I listen to a reader, but the only reader I hear is me. I am always writing to myself. So very possibly I’m committing an aggressive and hostile act toward myself.

INTERVIEWER

So when you ask, as you do in many nonfiction pieces, “Do you get the point?” you are really asking if you yourself get the point.

DIDION

Yes. Once in a while, when I first started to write pieces, I would try to write to a reader other than myself. I always failed. I would freeze up.

…

INTERVIEWER

You say you treasure privacy, that “being left alone and leaving others alone is regarded by members of my family as the highest form of human endeavor.” How does this mesh with writing personal essays, particularly the first column you did for Life where you felt it imperative to inform the reader that you were at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel in lieu of getting a divorce?

DIDION

I don’t know. I could say that I was writing to myself, and of course I was, but it’s a little more complicated than that. I mean the fact that eleven million people were going to see that page didn’t exactly escape my attention. There’s a lot of mystery to me about writing and performing and showing off in general. I know a singer who throws up every time she has to go onstage. But she still goes on.

INTERVIEWER

Did any writer influence you more than others?

DIDION

I always say Hemingway, because he taught me how sentences worked. When I was fifteen or sixteen I would type out his stories to learn how the sentences worked. I taught myself to type at the same time. A few years ago when I was teaching a course at Berkeley I reread A Farewell to Arms and fell right back into those sentences. I mean they’re perfect sentences. Very direct sentences, smooth rivers, clear water over granite, no sinkholes.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve called Henry James an influence.

DIDION

He wrote perfect sentences, too, but very indirect, very complicated. Sentences with sinkholes. You could drown in them. I wouldn’t dare to write one. I’m not even sure I’d dare to read James again. I loved those novels so much that I was paralyzed by them for a long time. All those possibilities. All that perfectly reconciled style. It made me afraid to put words down.

INTERVIEWER

I wonder if some of your nonfiction pieces aren’t shaped as a single Jamesian sentence.

DIDION

That would be the ideal, wouldn’t it. An entire piece—eight, ten, twenty pages—strung on a single sentence. Actually, the sentences in my nonfiction are far more complicated than the sentences in my fiction. More clauses. More semicolons. I don’t seem to hear that many clauses when I’m writing a novel.

INTERVIEWER

You have said that once you have your first sentence you’ve got your piece. That’s what Hemingway said. All he needed was his first sentence and he had his short story.

DIDION

What’s so hard about that first sentence is that you’re stuck with it. Everything else is going to flow out of that sentence. And by the time you’ve laid down the first two sentences, your options are all gone.

INTERVIEWER

The first is the gesture, the second is the commitment.

DIDION

Yes, and the last sentence in a piece is another adventure. It should open the piece up. It should make you go back and start reading from page one. That’s how it should be, but it doesn’t always work. I think of writing anything at all as a kind of high-wire act. The minute you start putting words on paper you’re eliminating possibilities. Unless you’re Henry James.

INTERVIEWER

I wonder if your ethic—what you call your “harsh Protestant ethic”—doesn’t close things up for you, doesn’t hinder your struggle to keep all the possibilities open.

DIDION

I suppose that’s part of the dynamic. I start a book and I want to make it perfect, want it to turn every color, want it to be the world. Ten pages in, I’ve already blown it, limited it, made it less, marred it. That’s very discouraging. I hate the book at that point. After a while I arrive at an accommodation: Well, it’s not the ideal, it’s not the perfect object I wanted to make, but maybe—if I go ahead and finish it anyway—I can get it right next time. Maybe I can have another chance.

INTERVIEWER

Have any women writers been strong influences?

DIDION

I think only in the sense of being models for a life, not for a style. I think that the Brontës probably encouraged my own delusions of theatricality. Something about George Eliot attracted me a great deal. I think I was not temperamentally attuned to either Jane Austen or Virginia Woolf.

INTERVIEWER

What are the disadvantages, if any, of being a woman writer?

DIDION

When I was starting to write—in the late fifties, early sixties—there was a kind of social tradition in which male novelists could operate. Hard drinkers, bad livers. Wives, wars, big fish, Africa, Paris, no second acts. A man who wrote novels had a role in the world, and he could play that role and do whatever he wanted behind it. A woman who wrote novels had no particular role. Women who wrote novels were quite often perceived as invalids. Carson McCullers, Jane Bowles. Flannery O’Connor, of course. Novels by women tended to be described, even by their publishers, as sensitive. I’m not sure this is so true anymore, but it certainly was at the time, and I didn’t much like it. I dealt with it the same way I deal with everything. I just tended my own garden, didn’t pay much attention, behaved—I suppose—deviously. I mean I didn’t actually let too many people know what I was doing.

INTERVIEWER

Advantages?

DIDION

The advantages would probably be precisely the same as the disadvantages. A certain amount of resistance is good for anybody. It keeps you awake.

…

INTERVIEWER

What misapprehensions, illusions and so forth have you had to struggle against in your life? In a commencement address you once said there were many.

DIDION

All kinds. I was one of those children who tended to perceive the world in terms of things read about it. I began with a literary idea of experience, and I still don’t know where all the lies are. For example, it may not be true that people who try to fly always burst into flames and fall. That may not be true at all. In fact people do fly, and land safely. But I don’t really believe that. I still see Icarus. I don’t seem to have a set of physical facts at my disposal, don’t seem to understand how things really work. I just have an idea of how they work, which is always trouble. As Henry James told us.

INTERVIEWER

You seem to live your life on the edge, or, at least, on the literary idea of the edge.

DIDION

Again, it’s a literary idea, and it derives from what engaged me imaginatively as a child. I can recall disapproving of the golden mean, always thinking there was more to be learned from the dark journey. The dark journey engaged me more. I once had in mind a very light novel, all surface, all conversations and memories and recollections of some people in Honolulu who were getting along fine, one or two misapprehensions about the past notwithstanding. Well, I’m working on that book now, but it’s not running that way at all. Not at all.

INTERVIEWER

It always turns into danger and apocalypse.

DIDION

Well, I grew up in a dangerous landscape. I think people are more affected than they know by landscapes and weather. Sacramento was a very extreme place. It was very flat, flatter than most people can imagine, and I still favor flat horizons. The weather in Sacramento was as extreme as the landscape. There were two rivers, and these rivers would flood in the winter and run dry in the summer. Winter was cold rain and tulle fog. Summer was 100 degrees, 105 degrees, 110 degrees. Those extremes affect the way you deal with the world. It so happens that if you’re a writer the extremes show up. They don’t if you sell insurance.

Reading the complete interview here: Joan Didion, The Art of Fiction No. 71.

This letter to her 16-year-old self gives insight into Thuli Madonsela‘s life before she became South Africa’s formidable Public Protector – one of the few current SA government office bearers who retain any integrity. Read her report on the misuse of public funds at the private residence of President Jacob Zuma at Nkandla. You can tell between the lines of this letter that she had to learn early in life to be comfortable with making unpopular choices to be able to do the things she believed in.

The following is an extract from From Me to Me: Letters to my 16-and-a-half-year old self (Jacana Media, 2012), a collection of letters written by South Africans to their teenage selves.

26 April 2012

Dear Thuli

It is April 2012, 5 months before our big 5-0 birthday. I am your future. At the moment, you are 16-and-a half years old, doing grade 11, known as form four then, at Evelyn Baring High School in Swaziland, the year being 1979. You are wondering what you will be, caught between thoughts of pursuing medicine and law. Your pastor’s disapproving views on the latter are not in any way helpful. I know you are socially awkward, plagued by a nagging feeling of being unloved and ugly.

It is April 2012, 5 months before our big 5-0 birthday. I am your future. At the moment, you are 16-and-a half years old, doing grade 11, known as form four then, at Evelyn Baring High School in Swaziland, the year being 1979. You are wondering what you will be, caught between thoughts of pursuing medicine and law. Your pastor’s disapproving views on the latter are not in any way helpful. I know you are socially awkward, plagued by a nagging feeling of being unloved and ugly.

Perhaps this comes from being teased about your big head and, more recently, two of your academically inferior classmates have started taunting you, too. Having two sisters whose beauty is always noticed and praised has not helped either. Secure in your academic prowess – for which you are always praised at home and at school – you are regarded as helpful and relied on by your family, friends, teachers and your church. This makes you feel significant. You will excel, academically, throughout your life and this will bring you to where you are right now. I’m writing to tell you to relax because you are a perfect expression of God’s magnificence.

You are the mother of two wonderful children, a beautiful daughter Wenzile Una and a handsome son Mbusowabantu “Wantu” Fidel. Your fears of being unlovable were unfounded. You have been loved and supported beyond measure throughout your life. Today, you are the nation’s Public Protector – a very responsible position that helps curb excesses in the exercise of public power while enabling the people to exact justice for state wrongs. You had the privilege of playing some role in bringing about change in this country, including the drafting of the new constitution that saw Nelson Mandela become the first black President. Mama was right, education is the great leveler. I’m glad I listened to her.

You have experienced tough times and great times, been met with nurturers and detractors, but all these life lessons have been necessary to help you bloom. You have come to realize that you are perfect for your life’s purpose. You’ve always been a dreamer, an eternal optimist. Keep dreaming, for dreams have wings. But live consciously and take time to smell the roses otherwise life will pass you by, including the opportunity to appreciate the finite precious moments you will enjoy with your late partner, younger sisters and parents.

Above all, remember that love is everything and don’t forget to forgive yourself and others.

Love you unconditionally,

Thuli Nomkhosi Madonsela (Your older Self)

“All these dead suns, these posthumous rays which take millions of light-years to reach us, asteroids, fragments of dead worlds, shattered and exploded, old moons, flawed and cankered, crusts, sores, blotches, cold lupus, devouring leprosy, sanies, and that last drop of pearl-like light, the purest of all, sweating at the highest point of the firmament and about to fall… is not a tear nor a dewdrop, but a drop of pus. The universe is in the process of decomposing and, like a cemetery, it swarms with becoming and smells good. The stars are unguent-bearing and throb feverishly; each ray carries seeds sown in the brain of man, and they are the seeds of destruction. Grey matter contains sunspots that eat into the whole circumference of the brain. It is an index of disintegration. Thought is a pestilence.”

— Blaise Cendrars, from Sky, the 1992 English translation of Le Lotissement du Ciel (1949).

Sky, the last of Cendrar’s four autobiographical volumes, is a collage of prose poetry, travel writing, reportage, detective story, and personal memoir.

“He recounts his adventures in Russia during the revolution of 1905, in the trenches of World War I (where he lost his right arm), in Brazil in the 1920s, and behind the lines during World War II. The two wars run throughout as a unifying thread. As the title announces, this is a memoir of the sky – of Cendrars’s love of birds, levitation, and aviation. The opening of the book finds Cendrars, the great adventurer and traveler, sailing back from Brazil to Paris with 250 multi-colored birds, hoping to bring at least one of them alive to a child he loves.

The second part moves back and forth between the author’s recollections of life as a war correspondent in 1940 and an encyclopedic discourse on levitation he wrote in search of a patron saint of aviation (perhaps as compensation for the death of his young son, Remy, who was a pilot during the war). With unmatched exuberance, Cendrars writes on poetry, myths, existentialism, his life in Paris between the wars with the painter Delaunay and the Dadaists, and his exotic adventuresin Brazil. His anecdotes of Russia, where he was a jeweller’s assistant, are compelling and funny. His fiercely imaginative stories, such as one about a Brazilian coffee plantation owner who, obsessed with his love for Sarah Bernhardt, retreats into the wilderness, are magical.”

(I found this review HERE.)

“Almost every day I can feel myself suffering mainly in the head, I can explain the pain to myself but knowing it comes from an inflammation of my imagination doesn’t prevent it being reality itself. What’s more I’d be crazy not to go crazy. We don’t know what an illness is. On awful hurts we plaster little old words, as if we could think hell with a paper bandage.”

― Hélène Cixous, Hyperdream

To switch for a moment to conceptual language: Power is indeed of the essence of all government, but violence is not. Violence is by nature instrumental; like all means, it always stands in need of guidance and justification through the end it pursues. And what needs justification by something else cannot be the essence of anything. The end of war – end taken in its twofold meaning – is peace or victory; but to the question “And what is the end of peace?” there is no answer. Peace is an absolute, even though in recorded history periods of warfare have nearly always outlasted periods of peace. Power is in the same category; it is, as they say, “an end in itself.” (This, of course, is not to deny that governments pursue policies and employ their power to achieve prescribed goals. But the power structure itself precedes and outlasts all aims, so that power, far from being the means to an end, is actually the very condition enabling a group of people to think and act in terms of the means-end category.)

And since government is essentially organized and institutionalized power, the current question “What is the end of government?” does not make much sense either. The answer will be either question-begging – to enable men to live together – or dangerously utopian – to promote happiness or to realize a classless society or some other nonpolitical ideal, which if tried out in earnest cannot but end in some kind of tyranny.

Power needs no justification, being inherent in the very existence of political communities; what it does need is legitimacy. The common treatment of these two words as synonyms is no less misleading and confusing than the current equation of obedience and support. Power springs up whenever people get together and act in concert, but it derives its legitimacy from the initial getting together rather than from any action that then may follow. Legitimacy, when challenged, bases itself on an appeal to the past, while justification relates to an end that lies in the future.

Violence can be justifiable, but it never will be legitimate. Its justification loses in plausibility the farther its intended end recedes into the future. No one questions the use of violence in self-defense, because the danger is not only clear but also present, and the end justifying the means is immediate.

Violence can be justifiable, but it never will be legitimate. Its justification loses in plausibility the farther its intended end recedes into the future. No one questions the use of violence in self-defense, because the danger is not only clear but also present, and the end justifying the means is immediate.

Power and violence, though they are distinct phenomena, usually appear together. Wherever they are combined, power, we have found, is the primary and predominant factor. The situation, however, is entirely different when we deal with them in their pure states – as, for instance, with foreign invasion and occupation. We saw that the current equation of violence with power rests on government’s being understood as domination of man over man by means of violence. If a foreign conqueror is confronted by an impotent government and by a nation unused to the exercise of political power, it is easy for him to achieve such domination. In all other cases the difficulties are great indeed, and the occupying invader will try immediately to establish Quisling governments, that is, to find a native power base to support his dominion. The head-on clash between Russian tanks and the entirely nonviolent resistance of the Czechoslovak people is a textbook case of a confrontation between violence and power in their pure states. But while domination in such an instance is difficult to achieve, it is not impossible.

Violence, we must remember, does not depend on numbers or opinions, but on implements, and the implements of violence, as I mentioned before, like all other tools, increase and multiply human strength. Those who oppose violence with mere power will soon find that they are confronted not by men but by men’s artifacts, whose inhumanity and destructive effectiveness increase in proportion to the distance separating the opponents. Violence can always destroy power; out of the barrel of a gun grows the most effective command, resulting in the most instant and perfect obedience. What never can grow out of it is power.

To research (English definition): “To search for something.”

To research (English definition): “To search for something.”

Rechercher (French definition): “To search for, to look for” and also “to search again, to look for again”.

Both “search” and “research” are the same word in French, it seems. This makes sense: even if something was once common knowledge, after it is hidden it is no longer “there”; it has fallen from awareness. So you have to seek for it again, that which is not there. In “research”, you never know what is actually there until you find it, or there would be no need to look. You dis-cover it again, un-cover it anew.

Archives are fascinating places of preservation-with-intent to look in, and they are always tantalisingly incomplete, however exhaustive… But nothing beats the thrill of finding a treasure hoard saved by happenstance.

To “ondersoek” , in Afrikaans, is to look under other things… The term implies a palimpsestic patina, an accretion, a build-up of layers that must be lifted, peeled off to see underneath… the mother lode, the genealogy. Sometimes you know exactly what you are looking for; sometimes you don’t. You may only have a misty hope that there is anything there at all. It can be useful to lose focus, too, because you become open to other routes, other offshoots, that may take you further than your original hunch.

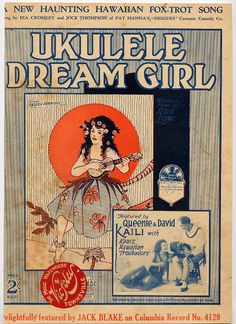

On Saturday, in a poky little shop in Kalk Bay, I found a trove of old sheet music: popular tunes from the 1920s and 1930s, the top few layers of it in torn, grubby disarray. A thrill ran through my fingertips as I started re-moving each sheet from the pile, putting it aside systematically. There was nothing of great interest until I got quite a way below the dusty surface layers, where most people’s patience obviously runs out (this is the trick with digging – to delve deeper, to expend more energy, more time than everyone else – om onder te soek, for there lies the gold). There was no way I could stop.

Buried in the pile, under piano exercise books, I found something that really astounded me… it almost made me shout for joy: many, many of the scores had ukulele chord diagrams on them! In all the popular sheet music I had ever been acquainted with before this, these diagrams were provided for guitar – with five lines for the five strings. These all had only four lines. It became clear to me on seeing this that, along with piano, ukulele was most likely the popular amateur instrument of choice back in the 1920s to 1940s, and not guitar. It makes sense when you listen to the jazziness of the pop arrangements of the time, and how well the chord progressions work technically with a ukulele’s tuning – GCEA. I would suppose that the guitar ousted the uke in popularity with the ascent of blues and rock and folk, in which different chords and tunings predominate, and for which the guitar’s EADGBE tuning is a more natural fit… How lovely to realise that this instrument I play very amateurishly, considered a funny curiosity by most these days, was accorded far more value in the past!

What this little discovery means for me, practically, is that I can now play all these very old jazzy tunes with no in-depth knowledge of musical theory. Even the songs I have never heard before can be found with a bit of effort on the internet, listened to, and re-played, provided someone else along the way has seen their value. As long as they were ever recorded, be it on wax cylinder or 78rpm, they may have been digitised. And, as they spin up on my hard drive, a vortex is created, opening a wormhole back to the instant that band played for the first time as the cylinder turned. And the song comes back from the dead as my fingers form the chord shapes, stutters back to life as I sing my breath into the words. Technology is powerful magic, all the more so when it takes account of its historicity.

Information technology is not only about making the future more slick and manageable; it is also about keeping the past accessible… Essentially it is about conquering linear time and space. The prolific recording of moments allows us to live unconstrained by the present moment and space we’re in, almost continuously if we so wish… (For example, people sit on Facebook as they are out for coffee with a friend. Once they have “checked in” at the cafe, they check out what other people are doing elsewhere on their phones, then frame themselves carefully for a photo in that space and capture the moment, uploading it to join the feed for others who are moving through spaces connected via radio waves to know about. Very little other than eating, drinking and self-referential preening is going on in most coffee spots.)

The sheer volume of recording that goes on now is unprecedented. Imagine reading Twitter logs in a century – every ordinary so-and-so with a Twitter account, with their own account of an event… The hyper(in)significance of every moment of our lives being documented is overwhelming to think about. How will historians of the future ever manage to filter out the noise from the signal and deduce anything?

Or, will the noise be the signal – the fragments the whole? How does this affect our memories, our critical faculties, our creativity, our relationships? New technologies confer on us immense power that should be used wisely and with sober discernment, not trivially… as that dumb what’s-her-face model Leandra found out last week when tweeting 140 racially offensive characters cost her her modelling career and dignity, with satisfying, devastating swiftness!

So, anyway, I pulled out a large wad of music sheets; slowly, carefully replaced what I didn’t take for someone else to find. Tried to conceal my excitement as I got to the till; thwacked the pile down and asked nonchalantly, “How much for this old stuff?”

“Two rand a sheet.” After counting to fifteen the old guy stopped and said “I can’t be bothered to count higher than fifteen – it’s yours for thirty bucks.”

I paid thirty rand for all of it. That’s less than a cocktail or a sandwich in the seaside cafes lining that road. So few people seem to see value in this stuff. Not even antique dealers. To them it’s just quaint ephemera.

Research involves following the intuition, the hunch that something lies hidden out of time, out of sight, out of mind: perhaps recorded imperfectly, decaying, deliberately saved. Or, like these priceless music sheets, just debris left in a place where it makes no sense to anyone who has stumbled across it yet… In danger of being lost forever if someone doesn’t come along with enough focused curiosity to re-cognise it as valuable, to think it back into meaningful connection with right now.

To me, the serendipity of finds like Saturday’s feels more than coincidental. If the person looking didn’t happen to be me there at that precise moment, it would probably have been a non-event. Even if it were the me of last year leafing through, I wouldn’t have known what I was looking for. Would have seen the music but not had a ukulele and maybe not noticed that the chord diagrams had only four strings, not five. The me of just a few months back would have seen the music with interest but not known the extent of the 78rpm archive online (having become aware of the degree of coverage of obscure songs through something I have been working on in the past month) and so left it because I didn’t know the songs and didn’t know there was a way to hear them. I don’t often look through second hand stores these days, broke as I am. On Saturday, something compelled me to step inside as I was passing. It felt as if me and the music were drawn together. It felt magical.

For a while longer, Klausner fussed about with the wires in the black box; then he straightened up and in a soft excited whisper said, “Now we’ll try again… We’ll take it out into the garden this time… and then perhaps, perhaps… the reception will be better. Lift it up now… carefully… Oh, my God, it’s heavy!”

He carried the box to the door, found that he couldn’t open the door without putting it down, carried it back, put it on the bench, opened the door, and then carried it with some difficulty into the garden. He placed the box carefully on a small wooden table that stood on the lawn. He returned to the shed and fetched a pair of earphones. He plugged the wire connections from the earphones into the machine and put the earphones over his ears. The movements of his hands were quick and precise. He was excited, and breathed loudly and quickly through his mouth. He kept on talking to himself with little words of comfort and encouragement, as though he were afraid–afraid that the machine might not work and afraid also of what might happen if it did. He stood there in the garden beside the wooden table, so pale, small and thin that he looked like an ancient, consumptive, bespectacled child.

The sun had gone down. There was no wind, no sound at all. From where he stood, he could see over a low fence into the next garden, and there was a woman walking down the garden with a flower-basket on her arm. He watched her for a while without thinking about her at all. Then he turned to the box on the table and pressed a switch on its front. He put his left hand on the volume control and his right hand on the knob that moved a needle across a large central dial, like the wavelength dial of a radio. The dial was marked with many numbers, in a series of bands, starting at 15,000 and going on up to 1,000,000. And now he was bending forward over the machine. His head was cocked to one side in a tense, listening attitude. His right hand was beginning to turn the knob.

The needle was travelling slowly across the dial, so slowly he could hardly see it move, and in the earphones he could hear a faint, spasmodic crackling. Behind this crackling sound he could hear a distant humming tone which was the noise of the machine itself, but that was all. As he listened, he became conscious of a curious sensation, a feeling that his ears were stretching out away from his head, that each ear was connected to his head by a thin stiff wire, like a tentacle, and that the wires were lengthening, that the ears were going up and up towards a secret and forbidden territory, a dangerous ultrasonic region where ears had never been before and had no right to be. The little needle crept slowly across the dial, and suddenly he heard a shriek, a frightful piercing shriek, and he jumped and dropped his hands, catching hold of the edge of the table.

He stared around him as if expecting to see the person who had shrieked. There was no one in sight except the woman in the garden next door, and it was certainly not she. She was bending down, cutting yellow roses and putting them in her basket. Again it came–a throatless, inhuman shriek, sharp and short, very clear and cold. The note itself possessed a minor, metallic quality that he had never heard before.

Klausner looked around him, searching instinctively for the source of the noise. The woman next door was the only living thing in sight. He saw her reach down; take a rose stem in the fingers of one hand and snip the stem with a pair of scissors. Again he heard the scream. It came at the exact moment when the rose stem was cut. At this point, the woman straightened up, put the scissors in the basket with the roses and turned to walk away.

“Mrs Saunders!” Klausner shouted, his voice shrill with excitement. “Oh, Mrs Saunders!” And looking round, the woman saw her neighbour standing on his lawn–a fantastic, arm-waving little person with a pair of earphones on his head–calling to her in a voice so high and loud that she became alarmed. “Cut another one! Please cut another one quickly!”

She stood still, staring at him. “Why, Mr Klausner,” she said, “What’s the matter?”

“Please do as I ask,” he said. “Cut just one more rose!”

Mrs Saunders had always believed her neighbour to be a rather peculiar person; now it seemed that he had gone completely crazy. She wondered whether she should run into the house and fetch her husband. No, she thought. No, he’s harmless. I’ll just humour him.

“Certainly, Mr Klausner, if you like,” she said.

She took her scissors from the basket, bent down and snipped another rose. Again Klausner heard that frightful, throatless shriek in the earphones; again it came at the exact moment the rose stem was cut. He took off the earphones and ran to the fence that separated the two gardens. “All right,” he said. “That’s enough. No more. Please, no more.”

The woman stood there, a yellow rose in one hand, clippers in the other, looking at him.”I’m going to tell you something, Mrs Saunders,” he said, “something that you won’t believe.” He put his hands on top of the fence and peered at her intently through his thick spectacles. “You have, this evening, cut a basketful of roses. You have, with a sharp pair of scissors, cut through the stems of living things, and each rose that you cut screamed in the most terrible way. Did you know that, Mrs Saunders?”

“No,” she said. “I certainly didn’t know that.”

“It happens to be true,” he said. He was breathing rather rapidly, but he was trying to control his excitement. “I heard them shrieking. Each time you cut one, I heard the cry of pain. A very high-pitched sound, approximately one hundred and thirty-two thousand vibrations a second. You couldn’t possibly have heard it yourself. But I heard it.”

“Did you really, Mr Klausner?” She decided she would make a dash for the house in about five seconds.

“You might say,” he went on, “that a rose bush has no nervous system to feel with, no throat to cry with. You’d be right. It hasn’t. Not like ours, anyway. But how do you know, Mrs Saunders”–and here he leaned far over the fence and spoke in a fierce whisper, “how do you know that a rose bush doesn’t feel as much pain when someone cuts its stem in two as you would feel if someone cut your wrist off with a garden shears? How do you know that? It’s alive, isn’t it?”

“Yes, Mr Klausner. Oh, yes and good night.”

Quickly she turned and ran up the garden to her house. Klausner went back to the table. He put on the earphones and stood for a while listening. He could still hear the faint crackling sound and the humming noise of the machine, but nothing more. He bent down and took hold of a small white daisy growing on the lawn. He took it between thumb and forefinger and slowly pulled it upward and sideways until the stem broke. From the moment that he started pulling to the moment when the stem broke, he heard–he distinctly heard in the earphones–a faint high-pitched cry, curiously inanimate.

He took another daisy and did it again. Once more he heard the cry, but he wasn’t sure now that it expressed pain. No, it wasn’t pain; it was surprise. Or was it? It didn’t really express any of the feelings or emotions known to a human being. It was just a cry, a neutral, stony cry–a single, emotionless note, expressing nothing. It had been the same with the roses. He had been wrong in calling it a cry of pain. A flower probably didn’t feel pain. It felt something else which we didn’t know about–something called tom or spun or plinuckment, or anything you like.

He stood up and removed the earphones. It was getting dark and he could see pricks of light shining in the windows of the houses all around him. Carefully he picked up the black box from the table, carried it into the shed and put it on the workbench. Then he went out, locked the door behind him and walked up to the house.

The next morning Klausner was up as soon as it was light. He dressed and went straight to the shed. He picked up the machine and carried it outside,clasping it to his chest with both hands, walking unsteadily under its weight. He went past the house, out through the front gate, and across the road to the park.There he paused and looked around him; then he went on until he came to a large tree, a beech tree, and he placed the machine on the ground close to the trunk of the tree.

Quickly he went back to the house and got an axe from the coal cellar and carried it across the road into the park. He put the axe on the ground beside the tree. Then he looked around him again, peering nervously through his thick glasses in every direction. There was no one about. It was six in the morning.He put the earphones on his head and switched on the machine. He listened for a moment to the faint familiar humming sound; then he picked up the axe, took a stance with his legs wide apart and swung the axe as hard as he could at the base of the tree trunk.

The blade cut deep into the wood and stuck there, and at the instant of impact he heard a most extraordinary noise in the earphones. It was a new noise, unlike any he had heard before–a harsh, noteless, enormous noise, a growling, low pitched, screaming sound, not quick and short like the noise of the roses, but drawn out like a sob lasting for fully a minute, loudest at the moment when the axe struck, fading gradually fainter and fainter until it was gone.

—

Excerpted from Roald Dahl’s short story, “The Sound Machine”, first published in The New Yorker on September 17, 1949. Read the full story HERE.

When she does not find love, she may find poetry. Because she does not act, she observes, she feels, she records; a colour, a smile awakens profound echoes within her; her destiny is outside her, scattered in cities already built, on the faces of men already marked by life, she makes contact, she relishes with passion and yet in a manner more detached, more free, than that of a young man.

Being poorly integrated in the universe of humanity and hardly able to adapt herself therein, she, like the child, is able to see it objectively; instead of being interested solely in her grasp on things, she looks for their significance; she catches their special outlines, their unexpected metamorphoses. She rarely feels a bold creativeness, and usually she lacks the technique of self-expression; but in her conversation, her letters, her literary essays, her sketches, she manifests an original sensitivity.

The young girl throws herself into things with ardour, because she is not yet deprived of her transcendence; and the fact that she accomplishes nothing, that she is nothing, will make her impulses only the more passionate. Empty and unlimited, she seeks from within her nothingness to attain All.

― Simone de Beauvoir, from The Second Sex (first published in French as Le Deuxième Sexe in 1949)

If you’re interested in reading this hugely influential text, you can find it online HERE.

Excerpted from a thoughtful piece by Kayli Stollak, over at Hello Giggles.

Online we tell a golden version of our lives filled with accomplishments, strictly (and often unbelievably) fun times, and a never-ending well of wit. The glorified digital narrative that we construct of our lives worries me like a 1950’s housewife watching Elvis wiggle his hips on TV. Our modern-day record keeping seems wildly inaccurate to the truth of our inner lives. What is happening in our too-much-information-nation? But more importantly, what is happening with us? Behind all the selfies and sandwich shots, who are we?

In order to correct the imbalance of truth, I propose we start writing it down. We share so much of ourselves with the web, but do we take enough time accounting for our private lives in realm that is removed from the world of likes, comments and followers? The idea of keeping a journal is nothing new, but we’re living in a time where we could benefit from taking a personal inventory of who we are, lest we deceive our future selves through our revisionist digital autobiographies.

While our faces are buried in our phones, we risk missing the smaller details in life. If we don’t remember the bad, how can we possibly enjoy the good to the highest degree? With time, I’m concerned we’ll look back at our Facebook timelines and mistake the façade that we presented of ourselves as fact for who we actually were.

As a writer who spends a large (and probably unhealthy) amount of time writing about herself, I often hear the condemnation of navel gazing. Sure, it is narcissistic to think your life is exciting enough to put to paper, but is it really more self-centered than a side-angled pouty pose of you enjoying your fun-filled Saturday night in the club, posted to Instagram with hopes of garnering likes from your followers, confirming that, yes, you are hot? I would venture to say that the former is self-reflective and productive, while the latter is vapidity and belly-button eagle eye-ing at its worst.

I’m not recommending you go all “dear diary” and start documenting your daily rhythms by laboriously chronicling what you ate for breakfast, the jerk who cut you off on the freeway, or what your plans are for the weekend—if that works for you, do it, but there’s no need to pen a three volume memoir. What I’m championing is the process of jotting down your feelings, thoughts, conversations, inspirations, events that meant something to you now that you might benefit from reflecting on in the future. This is a dose of honesty for you today, in five months, in ten years, at 97. To look back on after your next break up, when you’re contemplating marriage, on your graduation, before a big interview, or simply on a rainy day.

Your notebook should be far from the manicured image you pimp out on Instagram, Facebook, OKCupid, etc. In Joan Didion’s 1966 essay “On Keeping a Notebook”, written before our over-stimulated minds were flooded with technology and its never-ending distractions, she explained, “We are not talking here about the kind of notebook that is patently for public consumption, a structural conceit for binding together a series of graceful pensées, we are talking about something private, about bits of the mind’s string too short to use, an indiscriminate and erratic assemblage with meaning only for its maker.”

For me, a piece of ‘mind string’ is the harmonica chords to ‘Piano Man’ scribbled in my notebook from 2008. A stranger might assume a bizarre Billy Joel fixation, but when I revisit them in my journal, the mess of notes and the triggered sound insist on memories of a motorcycle trip through Spain and feelings of maddening love. All you need is sentence, a word, a thought, and suddenly you remember who you actually were.

If I skip forward in my notebook to 2009 I stumble upon a string of doubts, the point where this love began to unravel. The same way the smell of sunscreen can instantly bring back memories of summer, a list labeled “Pros and Cons” reminds me of the creeping anxiety I felt for planning my future. My Facebook timeline, however, tells a different tale of a giddy girl with bangs who enjoys raves, beaches, and doing the limbo.

Didion advocated for the importance of preserving a part of yourself that in time you can return to. She wrote, “It all comes back. Perhaps it is difficult to see the value in having one’s self back in that kind of mood, but I do see it; I think we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not… We forget all too soon the things we thought we could never forget. We forget the loves and the betrayals alike, forget what we whispered and what screamed, forget who we were.”

Notebooks are fantastic tools for keeping in touch with our former selves that go far beyond the sculpted image we present on the web. I love delving back into my journals from middle school to the present, not because I’m a fan of the person I see there, but rather because I understand the benefit of knowing her.

I want to yell at my thirteen year-old self to please take off that padded bra andstop being in such a rush to grow up. I want to hold my fourteen year-old self and explain to her that you are the company you keep and the sooner she starts loving herself the better. I want to bitch slap my sixteen year-old self, she was one angsty girl. I want to tell my seventeen year-old self not to mistake lust for love and to please stop talking to that boy in the band that told you he learned how to play “Brown-Eyed Girl” for you when, in fact, your eyes are green. I want to stay up all night talking to my twenty year-old self, feeding off her energy and drinking up her thirst for spontaneity. I want to see the world through her eyes, she reminds me to believe in magic. I want to whisper in the ear of my twenty-three year-old self, and tell her that soon enough she will see that it really was a means to an end. I want to tell my twenty-five year old self to trust her gut and not settle, I want to remind her what love looks like and tell her that this is not it. But I can’t tell her any of that. All I can do is learn from her mistakes, be reminded of what to hold meaning to, take note of her intuition, celebrate the coincidences, and enjoy all the beautiful moments and connections made.

Although I already know how most of the stories end, it’s important to track the progress I’ve made, reminding me who I am and who I was. To draw my own attention to the larger patterns my tendencies and predilections make when I can see them from a bird’s eye view. A notebook can serve as a wake up call on what I may be rightly or wrongly romanticizing and what I may be purposefully forgetting. Notebooks give us a shot at staying honest and in touch with ourselves, something I think we should strive to be in this digital age.

Read the full article HERE. Thanks to Stella for sharing it.

somewhere in 2008 i sent friends and family a short account of a visit to hillbrows’ HIV testing site. to cut it short it was a nightmare, surreal. the counsellor sat me down, asked my age, the number of sexual partners blah blah. he then broke down HIV for me, this is what it is, blah. to tie a bow on it, dude then asked where my family was and if i had any younger siblings who would take care of me when i get too sick to do so. he hadn’t even drawn blood then. what followed was a small confrontation, he shut me up by stating, ‘i wouldn’t be so cocky before my ‘positive’ comes back.’

i took the test and walked down to the johannesburg art gallery. kay hassan eased my anger, his fathers’ music room reminded me of home, the people there who would have to take care of me if the clairvoyant counsellor had had a clearer crystal ball. i’d seen other counsellors before mr doom and gloom, they had been informative and quick to ease my nerves. he was a bad apple, i filed a complaint.

today i tried my local clinic on for size. with ‘kick start’ clinics closed i’ve struggled to find a testing site that’s free and near and last year i missed my december first test. woodstock community health centre sits just on the other side of mountain road. when electricians arrived too early for my husband to open for them, i ran home to open up and leave them with a short ‘to do’ before zipping back up the road to join the freebie queue. after my folder was called i waited a short 45 minutes (govt health care people, catch up) before i was asked to see a counsellor. as i stepped in another gentleman was called.

‘no, we’re not together,’ i offered.

‘yes, that’s fine. just both of you come in.’

‘oh, ok’

i’m in this weird room with a counsellor, a dude i met on the bench outside and i’m about to disclose my sexual history. i’m about to know how many people mr bench has been with. this is all too heady. i sit and giggle awkwardly. i’m thinking of my one night stands, i realize i don’t know as much about any of them as i’m about to find out about this stranger. i giggle some more then ask, ‘but how?’ at which i burst out laughing. the counsellor raises an eye brow, i cross and uncross my legs then clench my butt cheeks, got to stop laffing.

‘how old are you?’

the counsellor is barking at mr bench, who looks at me and i shrug my shoulders. a quiet knock introduces mr bench’s friend, his translator. the man is french. there’s four of us in the room and the translator is hot and about to find out i’m pretty easy and live around the corner. i need a smart phone. for ten minutes i sit listening as questions bounce from the counsellor to the translator and then finally to mr bench. it’s amusing, it’s someone else’s nightmare.

‘have you ever had anal sex?’

‘i’m sorry, i’m going to have to wait outside.’

my shoulders are shaking, my chest is tight. i am clenching an unclenching my fists. i’m biting at my lower lip and i want to punch the daylights out of our counsellor. my knees buckle a bit as i sit at the bench outside the office. i didn’t get mr bench’s name but i know a few things about him that should remain in the safety of ‘doctor patient privilege.’ i sat through it, i laughed about it. yes, i shouldn’t have been put in that position but it’s one thing to need a translator to buy milk and bread and quite another to have a second person know your status before you do. mr bench is just one dude, a home affairs glitch. shame. i’m just a sweet little asshole, who should have used better judgement. when they leave i can’t look either one in the eye, i’m ashamed and can’t wait to half die.

my turn comes and i ask the counsellor why they asked us both to come in.

‘it’s a faster turn around.’

if they prick us, do we not bleed?

Some links and excerpts from commentary that I have found to be worth reading today (I’ll add to this whenever I come across anything interesting – if anyone reading this has suggestions, please pass them on too):

From “The Contradictions of Mandela” – Zakes Mda in the New York Times opinion pages:

The claim is that the settlement reached between the A.N.C. and the white apartheid government was a fraud perpetrated on the black people, who have yet to get back the land stolen by whites during colonialism. Mandela’s government, critics say, focused on the cosmetics of reconciliation, while nothing materially changed in the lives of a majority of South Africans.

This movement, though not representative of the majority of black South Africans who still adore Mandela and his A.N.C., is gaining momentum, especially on university campuses.

I understand the frustrations of those young South Africans and I share their disillusionment. I, however, do not share their perspective on Mandela. I saw in him a skillful politician whose policy of reconciliation saved the country from a blood bath and ushered it into a period of democracy, human rights and tolerance. I admired him for his compassion and generosity, values that are not usually associated with politicians. I also admired him for his integrity and loyalty.

But I fear that, for Mandela, loyalty went too far. The corruption that we see today did not just suddenly erupt after his term in office; it took root during his time. He was loyal to his comrades to a fault, and was therefore blind to some of their misdeeds.

Read the rest of what Mda has to say HERE.

—

From “Mandela’s Socialist Failure” – Slavoj Zizek in the New York Times opinion pages

In South Africa, the miserable life of the poor majority broadly remains the same as under apartheid, and the rise of political and civil rights is counterbalanced by the growing insecurity, violence, and crime. The main change is that the old white ruling class is joined by the new black elite. Secondly, people remember the old African National Congress which promised not only the end of apartheid, but also more social justice, even a kind of socialism. This much more radical ANC past is gradually obliterated from our memory. No wonder that anger is growing among poor, black South Africans.

South Africa in this respect is just one version of the recurrent story of the contemporary left. A leader or party is elected with universal enthusiasm, promising a “new world” — but, then, sooner or later, they stumble upon the key dilemma: does one dare to touch the capitalist mechanisms, or does one decide to “play the game”? If one disturbs these mechanisms, one is very swiftly “punished” by market perturbations, economic chaos, and the rest. This is why it is all too simple to criticize Mandela for abandoning the socialist perspective after the end of apartheid: did he really have a choice? Was the move towards socialism a real option?

It is easy to ridicule Ayn Rand, but there is a grain of truth in the famous “hymn to money” from her novel Atlas Shrugged: “Until and unless you discover that money is the root of all good, you ask for your own destruction. When money ceases to become the means by which men deal with one another, then men become the tools of other men. Blood, whips and guns or dollars. Take your choice – there is no other.” Did Marx not say something similar in his well-known formula of how, in the universe of commodities, “relations between people assume the guise of relations among things”?

In the market economy, relations between people can appear as relations of mutually recognized freedom and equality: domination is no longer directly enacted and visible as such. What is problematic is Rand’s underlying premise: that the only choice is between direct and indirect relations of domination and exploitation, with any alternative dismissed as utopian. However, one should nonetheless bear in mind the moment of truth in Rand’s otherwise ridiculously ideological claim: the great lesson of state socialism was effectively that a direct abolishment of private property and market-regulated exchange, lacking concrete forms of social regulation of the process of production, necessarily resuscitates direct relations of servitude and domination. If we merely abolish market (inclusive of market exploitation) without replacing it with a proper form of the Communist organization of production and exchange, domination returns with a vengeance, and with it direct exploitation.

The general rule is that, when a revolt begins against an oppressive half-democratic regime, as was the case in the Middle East in 2011, it is easy to mobilize large crowds with slogans which one cannot but characterize as crowd pleasers – for democracy, against corruption, for instance. But then we gradually approach more difficult choices: when our revolt succeeds in its direct goal, we come to realize that what really bothered us (our un-freedom, humiliation, social corruption, lack of prospect of a decent life) goes on in a new guise. The ruling ideology mobilizes here its entire arsenal to prevent us from reaching this radical conclusion. They start to tell us that democratic freedom brings its own responsibility, that it comes at a price, that we are not yet mature if we expect too much from democracy. In this way, they blame us for our failure: in a free society, so we are told, we are all capitalist investing in our lives, deciding to put more into our education than into having fun if we want to succeed…

… If we want to remain faithful to Mandela’s legacy, we should forget about celebratory crocodile tears and focus on the unfulfilled promises his leadership gave rise to. We can safely surmise that, on account of his doubtless moral and political greatness, he was at the end of his life also a bitter, old man, well aware how his very political triumph and his elevation into a universal hero was the mask of a bitter defeat. His universal glory is also a sign that he really didn’t disturb the global order of power.

Read Zizek’s full post HERE.

—

From “Nelson Mandela: The Crossing” – Richard Pithouse at SACSIS

[W]e need to be very clear that we did not undo many of the injustices that honed Mandela’s anger in the 1950s…

…But as Mandela returns from myth and into history we should not, amidst the humanizing details of his life as it was actually lived, or the morass into which the ANC has sunk, forget the principles for which he stood. We should not forget the bright strength of the Idea of Nelson Mandela.

Mandela was a revolutionary who was prepared to fight and to risk prison or death for his ideals – rational and humane ideals. In this age where empty posturing on Facebook or reciting banal clichés at NGO workshops is counted as militancy, where rhetoric often floats free of any serious attempts to organise or risk real confrontation, where the human is seldom the measure of the political, we would do well to recall Mandela as a man who brought principle and action together with resolute commitment.

Mandela was also a man whose ethical choices transcended rather than mirrored those of his oppressors. Amidst the on-going debasement of our political discourse into ever more crude posturing we would do well to remember that no radicalism can be counted as adequate to its situation if it allows that situation to constrain its vision and distort its conception of the ethical.

Read the full article by Pithouse HERE.

“… [P]erhaps the greatest tragedy of Mandela’s life isn’t that he spent almost thirty years jailed by well-heeled racists who tried to shatter millions of spirits through breaking his soul, but that there weren’t or aren’t nearly enough people like him.Because that’s South Africa now, a country long ago plunged headfirst so deep into the sewage of racial hatred that, for all Mandela’s efforts, it is still retching by the side of the swamp. Just imagine if Cape Town were London. Imagine seeing two million white people living in shacks and mud huts along the M25 as you make your way into the city, where most of the biggest houses and biggest jobs are occupied by a small, affluent to wealthy group of black people. There are no words for the resentment that would still simmer there.Nelson Mandela was not a god, floating elegantly above us and saving us. He was utterly, thoroughly human, and he did all he did in spite of people like you. There is no need to name you because you know who you are, we know who you are, and you know we know that too. You didn’t break him in life, and you won’t shape him in death. You will try, wherever you are, and you will fail.”

Read the rest of the words at OKWONGA.COM.

“Society is like a stew. If you don’t stir it up every once in a while then a layer of scum floats to the top.”

“My loyalties will not be bound by national borders, or confined in time by one nation’s history, or limited in the spiritual dimension by one language and culture. I pledge my allegiance to the damned human race, and my everlasting love to the green hills of Earth, and my intimations of glory to the singing stars, to the very end of space and time.”

— From Confessions of a Barbarian: Selections from the Journals of Edward Abbey, 1951-1989 (Boston: Little, Brown 1994).

Excavating an ancient tomb in South Korea, archaeologists found the 4-centuries-old mummy of Eung-Tae Lee, who had died at the age of 30. Lying on his chest was this letter, written by his pregnant widow and addressed to the father of their unborn child:

Transcript

To Won’s Father

June 1, 1586You always said, “Dear, let’s live together until our hair turns grey and die on the same day.” How could you pass away without me? Who should I and our little boy listen to and how should we live? How could you go ahead of me?

How did you bring your heart to me and how did I bring my heart to you? Whenever we lay down together you always told me, “Dear, do other people cherish and love each other like we do? Are they really like us?” How could you leave all that behind and go ahead of me?

I just cannot live without you. I just want to go to you. Please take me to where you are. My feelings toward you I cannot forget in this world and my sorrow knows no limit. Where would I put my heart in now and how can I live with the child missing you?

Please look at this letter and tell me in detail in my dreams. Because I want to listen to your saying in detail in my dreams I write this letter and put it in. Look closely and talk to me.

When I give birth to the child in me, who should it call father? Can anyone fathom how I feel? There is no tragedy like this under the sky.

You are just in another place, and not in such a deep grief as I am. There is no limit and end to my sorrows that I write roughly. Please look closely at this letter and come to me in my dreams and show yourself in detail and tell me. I believe I can see you in my dreams. Come to me secretly and show yourself. There is no limit to what I want to say and I stop here.

Source: Letters of Note

When I was a girl, my life was music that was always getting louder.

When I was a girl, my life was music that was always getting louder.

Everything moved me.

A dog following a stranger. That made me feel so much.

A calendar that showed the wrong month. I could have cried over it.

I did.

Where the smoke from the chimney ended.

How an overturned bottle rested at the edge of a table.

I spent my life learning to feel less.

Every day I felt less.

Is that growing old? Or is it something worse?

You cannot protect yourself from sadness without protecting yourself from happiness.

— Jonathan Safran Foer, from Everything is Illuminated

Thanks to Lex for sharing this.

There is no man… however wise, who has not at some period of his youth said things, or lived in a way the consciousness of which is so unpleasant to him in later life that he would gladly, if he could, expunge it from his memory. And yet he ought not entirely to regret it, because he cannot be certain that he has indeed become a wise man—so far as it is possible for any of us to be wise—unless he has passed through all the fatuous or unwholesome incarnations by which that ultimate stage must be preceded.

I know that there are young fellows, the sons and grandsons of famous men, whose masters have instilled into them nobility of mind and moral refinement in their schooldays. They have, perhaps, when they look back upon their past lives, nothing to retract; they can, if they choose, publish a signed account of everything they have ever said or done; but they are poor creatures, feeble descendants of doctrinaires, and their wisdom is negative and sterile.

We are not provided with wisdom, we must discover it for ourselves, after a journey through the wilderness which no one else can take for us, an effort which no one can spare us, for our wisdom is the point of view from which we come at last to regard the world. The lives that you admire, the attitudes that seem noble to you, are not the result of training at home, by a father, or by masters at school, they have sprung from beginnings of a very different order, by reaction from the influence of everything evil or commonplace that prevailed around them. They represent a struggle and a victory.

— Marcel Proust, from Within a Budding Grove