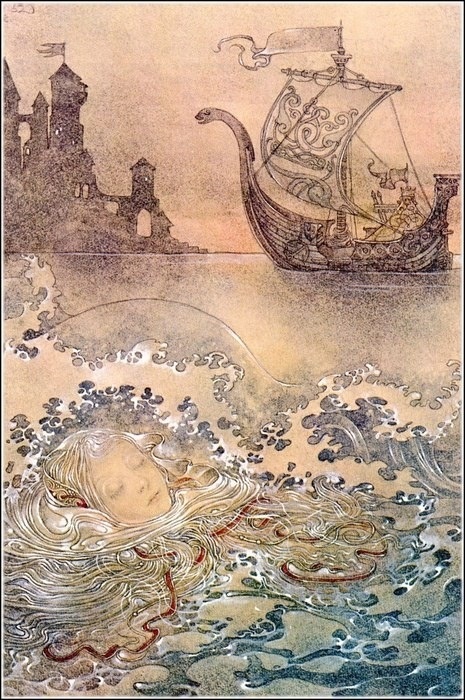

“Melancholy is a twilight state; suffering melts into it and becomes a sombre joy. Melancholy is the pleasure of being sad.”

– Victor Hugo, Toilers of the Sea

Melancholy is ambivalent and contradictory. Although it seems at once a very familiar term, it is extraordinarily elusive and enigmatic. It is something found not only in humans – whether pathological, psychological, or a mere passing mood – but in landscapes, seasons, and sounds. They too can be melancholy. Batman, Pierrot, and Hamlet are all melancholic characters, with traits like darkness, unrequited longing, and genius or heroism. Twilight, autumn and minor chords are also melancholy, evoking poignancy and the passing of time.

How is melancholy defined? A Field Guide to Melancholy traces out some of the historic traditions of melancholy, most of which remain today, revealing it to be an incredibly complex term. Samuel Johnson’s definition, in his eighteenth century Dictionary of the English Language, reveals melancholy’s multi-faceted nature was already well established by then: ‘A disease, supposed to proceed from a redundance of black bile; a kind of madness, in which the mind is always fixed on one object; a gloomy, pensive, discontented temper.’2 All of these aspects – disease, madness and temperament – continue to coalesce in the concept of melancholy, and rather than seeking a definitive definition or chronology, or a discipline-specific account, this book embraces contradiction and paradox: the very kernel of melancholy itself.

As an explicit promotion of the ideal of melancholy, the Field Guide extols the benefits of the pursuit of sadness, and questions the obsession with happiness in contemporary society. Rather than seeking an ‘architecture of happiness’, or resorting to Prozac-with-everything, it is proposed that melancholy is not a negative emotion, which for much of history it wasn’t – it was a desirable condition, sought for its ‘sweetness’ and intensity. It remains an important point of balance – a counter to the ‘loss of sadness’. Not grief, not mourning, not sorrow, yet all of those things.

Melancholy is profoundly interdisciplinary, and ranges across fields as diverse as medicine, literature, art, design, psychology and philosophy. It is over two millennia old as a concept, and its development predates the emergence of disciplines.While similarly enduring concepts have also been tackled by a breadth of disciplines such as philosophy, art and literature, melancholy alone extends across the spectrum of arts and sciences, with significant discourses in fields like psychiatry, as much as in art. Concepts with such an extensive period of development (the idea of ‘beauty’ for example) tend to go through a process of metamorphosis and end up meaning something distinctly different.3 Melancholy has been surprisingly stable. Despite the depth and breadth of investigation, the questions, ideas and contradictions which form the ‘constellation’4 of melancholy today are not dramatically different from those at any time in its history. There is a sense that, as psychoanalytical theorist Julia Kristeva puts it, melancholy is ‘essential and trans-historical’.5

Melancholy is a central characteristic of the human condition, and Hildegard of Bingen, the twelfth century abbess and mystic, believed it to have been formed at the moment that Adam sinned in taking the apple – when melancholy ‘curdled in his blood’.6 Modern day Slovenian philosopher, Slavoj Žižek, also positions melancholy, and its concern with loss and longing, at the very heart of the human condition, stating ‘melancholy (disappointment with all positive, empirical objects, none of which can satisfy our desire) is in fact the beginning of philosophy.’7

The complexity of the idea of melancholy means that it has oscillated between attempts to define it scientifically, and its embodiment within a more poetic ideal. As a very coarse generalisation, the scientific/psychological underpinnings of melancholy dominated the early period, from the late centuries BC when ideas on medicine were being formulated, while in later, mainly post-medieval times, the literary ideal became more significant. In recent decades, the rise of psychiatry has re-emphasised the scientific dimensions of melancholy. It was never a case of either/or, however, and both ideals, along with a multitude of other colourings, have persisted through history.

The essential nature of melancholy as a bodily as well as a purely mental state is grounded in the foundation of ideas on physiology; that it somehow relates to the body itself. These ideas are rooted in the ancient notion of ‘humours’. In Greek and Roman times humoralism was the foundation for an understanding of physiology, with the four humours ruling the body’s characteristics.

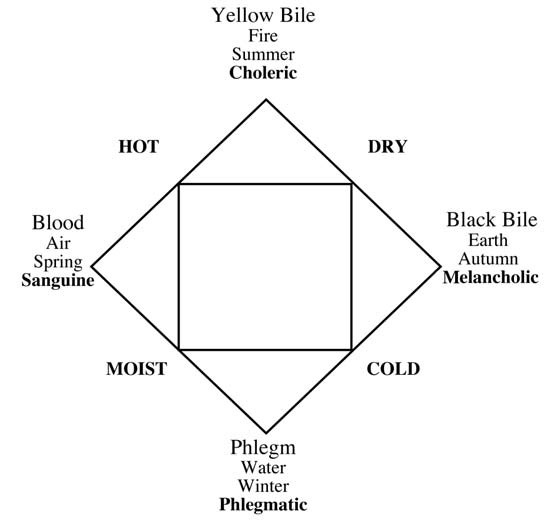

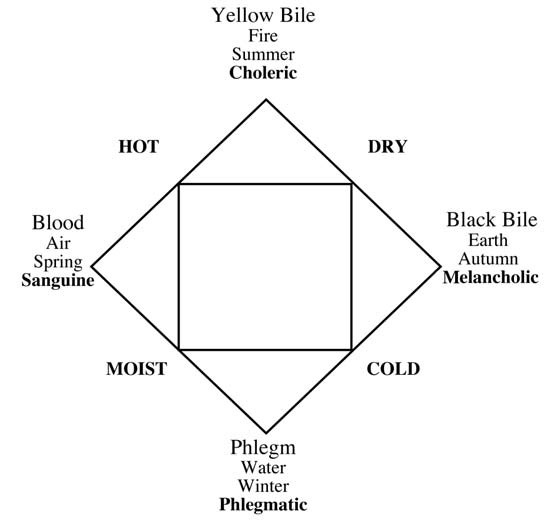

Phlegm, blood, yellow bile and black bile were believed to be the four governing elements, and each was ascribed to particular seasons, elements and temperaments. This can be expressed via a tetrad, or four-cornered diagram.

The Four Humours, adapted from Henry E Sigerist (1961) “A History of Medicine”, 2 vols New York: Oxford University Press, 2:232

The four-part divisions of temperament were echoed in a number of ways, as in the work of Alkindus, the ninth century Arab philosopher, who aligned the times of the day with particular dispositions. The tetrad could therefore be further embellished, with the first quarter of the day sanguine, second choleric, third melancholic and finally phlegmatic. Astrological allegiances reinforce the idea of four quadrants, so that Jupiter is sanguine, Mars choleric, Saturn is melancholy, and the moon or Venus is phlegmatic. The organs, too, are associated with the points of the humoric tetrad, with the liver sanguine, the gall bladder choleric, the spleen melancholic, and the brain/ lungs phlegmatic.

Melancholy, then, is associated with twilight, autumn, earth, the spleen, coldness and dryness, and the planet Saturn. All of these elements weave in and out of the history of melancholy, appearing in mythology, astrology, medicine, literature and art.The complementary humours and temperaments were sometimes hypothesised as balances, so that the opposite of one might be introduced as a remedy for an excess of another. For melancholy, the introduction of sanguine elements – blood, air and warmth – could counter the darkness. This could also work at an astrological level, as in the appearance of the magic square of Jupiter on the wall behind Albrecht Dürer’s iconic engraving Melencolia I, (1514) – the sign of Jupiter to introduce a sanguine balance to the saturnine melancholy angel.

Albrecht Dürer – Melencolia 1. Engraving, 1514.

In this early phase of the development of humoral thinking a key tension arose, as on one hand it was devised as a means of establishing degrees of wellness, but on the other it was a system of types of disposition. As Klibansky, Panofsky and Saxl put it, there were two quite different meanings to the terms sanguine, choleric, phlegmatic and melancholy, as either ‘pathological states or constitutional aptitudes’.9 Melancholy became far more connected with the idea of illness than the other temperaments, and was considered a ‘special problem’.

The blurry boundary between an illness and a mere temperament was a result of the fact that many of the symptoms of ‘melancholia’ were mental, and thus difficult to objectify, unlike something as apparent as a disfigurement or wound. The theory of the humours morphed into psychology and physiognomy, with particular traits or appearances associated with each temperament.

Melancholy was aligned with ‘the lisping, the bald, the stuttering and the hirsute’, and ‘emotional disturbances’ were considered as indicators of ‘mental melancholy’.10 Hippocrates in his Aphorismata, or ‘Aphorisms’, in 400 BC noted, ‘Constant anxiety and depression are signs of melancholy.’ Two centuries later the physician Galen, in an uncharacteristically succinct summation, noted that Hippocrates was ‘right in summing up all melancholy symptoms in the two following: Fear and Depression.’11

The foundations of the ideas on melancholy are fraught with complexity and contradiction, and this signals the beginning of a legacy of richness and debate. We have a love-hate relationship with melancholy, recognising its potential, yet fearing its connotations. What is needed is some kind of guide book, to know how to recognise it, where to find it – akin to the Observer’s Guides, the Blue Guides, or Gavin Pretor-Pinney’s The Cloudspotter’s Guide. Yet, to attempt to write a guide to such an amorphous concept as melancholy is overwhelmingly impossible, such is the breadth and depth of the topic, the disciplinary territories, the disputes, and the extensive creative outpourings. There is a tremendous sense of the infinite, like staring at stars, or at a room full of files, a daunting multitude. The approach is, therefore, to adopt the notion of the ‘constellation’, and to plot various points and co-ordinates, a join-the-dots approach to exploration which roams far and wide, and connects ideas and examples in a way which seeks new combinations and sometimes unexpected juxtapositions.

A Field Guide to Melancholy is therefore in itself a melancholic enterprise: for the writer, and the reader, the very idea of a ‘field guide’ to something so contradictory, so elusive, embodies the impossibility and futility that is central to melancholy’s yearning. Yet, it is this intangible, potent possibility which creates melancholy’s magnetism, recalling Joseph Campbell’s version of the Buddhist advice to “joyfully participate in the sorrows of the world”.12

Notes

1. Victor Hugo, Toilers of the Sea, vol. 3, p.159.

2. Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language, p.458, emphasis mine.

3. This constant shift in the development of concepts is well-illustrated by Umberto Eco (ed) (2004) History of Beauty, New York: Rizzoli, and his recent (2007) On Ugliness, New York: Rizzoli.

4. The term ‘constellation’ is Giorgio Agamben’s, and captures the sense of melancholy’s persistence as a collection of ideas, rather than one simple definition. See Giorgio Agamben, Stanzas:Word and Phantasm in Western Culture, p.19.

5. Julia Kristeva, Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia, p.258.

6. Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky and Fritz Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion and Art, p.79.

7. Slavoj Žižek, Did Somebody say Totalitarianism? Five Interventions on the (Mis)use of a Notion, p.148.

8. In Stanley W Jackson (1986), Melancholia and Depression: From Hippocratic Times to Modern Times, p.9.

9. Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky and Fritz Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion and Art, p.12.

10. ibid, p.15.

11. ibid, p.15, and n.42.

12. A phrase used by Campbell in his lectures, for example on the DVD Joseph Campbell (1998) Sukhavati. Acacia.

__

Excerpted from the introduction to Jacky Bowring’s A Field Guide to Melancholy, Oldcastle Books, 2008.

What world to which you do not belong

What world to which you do not belong